Mgmt Options Plantar Fasciitis Batt Tanji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J

Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J. Knüsel To cite this version: Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J. Knüsel. Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Wiley, 2013, Entheseal Changes and Occupation: Technical and Theoretical Advances and Their Applications, 23 (2), pp.135-146. 10.1002/oa.2289. hal-03147090 HAL Id: hal-03147090 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03147090 Submitted on 19 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Journal: International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Manuscript ID: OA-12-0089.R1 Wiley - ManuscriptFor type: Commentary Peer Review Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Villotte, Sébastien; University of Bradford, AGES Knusel, Chris; University of Exeter, Department of Archaeology entheses, enthesopathy, Musculoskeletal Stress Markers (MSM), Keywords: senescence, activity, hormones, animal models, clinical studies http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/oa Page 1 of 27 International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 1 2 3 Title: 4 5 Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes 6 7 8 Short title: 9 10 Understanding Entheseal Changes 11 12 13 Keywords: entheses; enthesopathy; Musculoskeletal Stress Markers (MSM); senescence; 14 15 activity; hormones; animal models; clinical studies 16 17 18 Authors: For Peer Review 19 20 Villotte S. -

Juvenile Spondyloarthropathies: Inflammation in Disguise

PP.qxd:06/15-2 Ped Perspectives 7/25/08 10:49 AM Page 2 APEDIATRIC Volume 17, Number 2 2008 Juvenile Spondyloarthropathieserspective Inflammation in DisguiseP by Evren Akin, M.D. The spondyloarthropathies are a group of inflammatory conditions that involve the spine (sacroiliitis and spondylitis), joints (asymmetric peripheral Case Study arthropathy) and tendons (enthesopathy). The clinical subsets of spondyloarthropathies constitute a wide spectrum, including: • Ankylosing spondylitis What does spondyloarthropathy • Psoriatic arthritis look like in a child? • Reactive arthritis • Inflammatory bowel disease associated with arthritis A 12-year-old boy is actively involved in sports. • Undifferentiated sacroiliitis When his right toe starts to hurt, overuse injury is Depending on the subtype, extra-articular manifestations might involve the eyes, thought to be the cause. The right toe eventually skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and heart. The most commonly accepted swells up, and he is referred to a rheumatologist to classification criteria for spondyloarthropathies are from the European evaluate for possible gout. Over the next few Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG). See Table 1. weeks, his right knee begins hurting as well. At the rheumatologist’s office, arthritis of the right second The juvenile spondyloarthropathies — which are the focus of this article — toe and the right knee is noted. Family history is might be defined as any spondyloarthropathy subtype that is diagnosed before remarkable for back stiffness in the father, which is age 17. It should be noted, however, that adult and juvenile spondyloar- reported as “due to sports participation.” thropathies exist on a continuum. In other words, many children diagnosed with a type of juvenile spondyloarthropathy will eventually fulfill criteria for Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor adult spondyloarthropathy. -

Atraumatic Bilateral Achilles Tendon Rupture: an Association of Systemic

378 Kotnis, Halstead, Hormbrey Acute compartment syndrome may be a of the body of gastrocnemius has been result of any trauma to the limb. The trauma is reported in athletes.7 8 This, however, is the J Accid Emerg Med: first published as 10.1136/emj.16.5.378 on 1 September 1999. Downloaded from usually a result of an open or closed fracture of first reported case of acute compartment the bones, or a crush injury to the limb. Other syndrome caused by a gastrocnemius muscle causes include haematoma, gun shot or stab rupture in a non-athlete. wounds, animal or insect bites, post-ischaemic swelling, vascular damage, electrical injuries, burns, prolonged tourniquet times, etc. Other Conclusion causes of compartment syndrome are genetic, Soft tissue injuries and muscle tears occur fre- iatrogenic, or acquired coagulopathies, infec- quently in athletes. Most injuries result from tion, nephrotic syndrome or any cause of direct trauma. Indirect trauma resulting in decreased tissue osmolarity and capillary per- muscle tears and ruptures can cause acute meability. compartment syndrome in athletes. It is also Chronic compartment syndrome is most important to keep in mind the possibility of typically an exercise induced condition charac- similar injuries in a non-athlete as well. More terised by a relative inadequacy of musculofas- research is needed to define optimal manage- cial compartment size producing chronic or ment patterns and potential strategies for recurring pain and/or disability. It is seen in injury prevention. athletes, who often have recurring leg pain that Conflict of interest: none. starts after they have been exercising for some Funding: none. -

Fibular Stress Fractures in Runners

Fibular Stress Fractures in Runners Robert C. Dugan, MS, and Robert D'Ambrosia, MD New Orleans, Louisiana The incidence of stress fractures of the fibula and tibia is in creasing with the growing emphasis on and participation in jog ging and aerobic exercise. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion on the part of the clinician. A thorough history and physical examination with appropriate x-ray examination and often technetium 99 methylene diphosphonate scan are re quired for the diagnosis. With the advent of the scan, earlier diagnosis is possible and earlier return to activity is realized. The treatment is complete rest from the precipitating activity and a gradual return only after there is no longer any pain on deep palpation at the fracture site. X-ray findings may persist 4 to 6 months after the initial injury. A stress fracture is best described as a dynamic tigue fracture, spontaneous fracture, pseudofrac clinical syndrome characterized by typical symp ture, and march fracture. The condition was first toms, physical signs, and findings on plain x-ray described in the early 1900s, mostly by military film and bone scan.1 It is a partial or incomplete physicians.5 The first report from the private set fracture resulting from an inability to withstand ting was in 1940, by Weaver and Francisco,6 who nonviolent stress that is applied in a rhythmic, re proposed the term pseudofracture to describe a peated, subthreshold manner.2 The tibiofibular lesion that always occurred in the upper third of joint is the most frequent site.3 Almost invariably one or both tibiae and was characterized on roent the fracture is found in the distal third of the fibula, genograms by a localized area of periosteal thick although isolated cases of proximal fibular frac ening and new bone formation over what appeared tures have also been reported.4 The symptoms are to be an incomplete V-shaped fracture in the cor exacerbated by stress and relieved by inactivity. -

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Name of Blue Advantage Policy: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Policy #: 076 Latest Review Date: November 2020 Category: Medical Policy Grade: A BACKGROUND: Blue Advantage medical policy does not conflict with Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), Local Medical Review Policies (LMRPs) or National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) or with coverage provisions in Medicare manuals, instructions or operational policy letters. In order to be covered by Blue Advantage the service shall be reasonable and necessary under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, Section 1862(a)(1)(A). The service is considered reasonable and necessary if it is determined that the service is: 1. Safe and effective; 2. Not experimental or investigational*; 3. Appropriate, including duration and frequency that is considered appropriate for the service, in terms of whether it is: • Furnished in accordance with accepted standards of medical practice for the diagnosis or treatment of the patient’s condition or to improve the function of a malformed body member; • Furnished in a setting appropriate to the patient’s medical needs and condition; • Ordered and furnished by qualified personnel; • One that meets, but does not exceed, the patient’s medical need; and • At least as beneficial as an existing and available medically appropriate alternative. *Routine costs of qualifying clinical trial services with dates of service on or after September 19, 2000 which meet the requirements of the Clinical Trials NCD are considered reasonable and necessary by Medicare. Providers should bill Original Medicare for covered services that are related to clinical trials that meet Medicare requirements (Refer to Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Chapter 1, Section 310 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual Chapter 32, Sections 69.0-69.11). -

The Painful Heel Comparative Study in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reiter's Syndrome, and Generalized Osteoarthrosis

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.36.4.343 on 1 August 1977. Downloaded from Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 1977, 36, 343-348 The painful heel Comparative study in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthrosis J. C. GERSTER, T. L. VISCHER, A. BENNANI, AND G. H. FALLET From the Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland SUMMARY This study presents the frequency of severe and mild talalgias in unselected, consecutive patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthosis. Achilles tendinitis and plantar fasciitis caused a severe talalgia and they were observed mainly in males with Reiter's syndrome or ankylosing spondylitis. On the other hand, sub-Achilles bursitis more frequently affected women with rheumatoid arthritis and rarely gave rise to severe talalgias. The simple calcaneal spur was associated with generalized osteoarthrosis and its frequency increased with age. This condition was not related to talalgias. Finally, clinical and radiological involvement of the subtalar and midtarsal joints were observed mainly in rheumatoid arthritis and occasionally caused apes valgoplanus. copyright. A 'painful heel' syndrome occurs at times in patients psoriasis, urethritis, conjunctivitis, or enterocolitis. with inflammatory rheumatic disease or osteo- The antigen HLA B27 was present in 29 patients arthrosis, causing significant clinical problems. Very (80%O). few studies have investigated the frequency and characteristics of this syndrome. Therefore we have RS 16 PATIENTS studied unselected groups of patients with rheuma- All of our patients had the complete triad (non- toid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), gonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis). -

9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease

Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease 121 9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease A. Stäbler CONTENTS Shoulder pain and chronic reduced function are fre- quently heard complaints in an orthopaedic outpa- 9.1 Defi nition of Impingement Syndrome 122 tient department. The symptoms are often related to 9.2 Stages of Impingement 123 the unique anatomic relationships present around the 9.3 Imaging of Impingement Syndrome: Uri Imaging Modalities 123 glenohumeral joint ( 1997). Impingement of the 9.3.1 Radiography 123 rotator cuff and adjacent bursa between the humeral 9.3.2 Ultrasound 126 head and the coracoacromial arch are among the most 9.3.3 Arthrography 126 common causes of shoulder pain. Neer noted that 9.3.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging 127 elevation of the arm, particularly in internal rotation, 9.3.4.1 Sequences 127 9.3.4.2 Gadolinium 128 causes the critical area of the cuff to pass under the 9.3.4.3 MR Arthrography 128 coracoacromial arch. In cadaver dissections he found 9.4 Imaging Findings in Impingement Syndrome alterations attributable to mechanical impingement and Rotator Cuff Tears 130 including a ridge of proliferative spurs and excres- 9.4.1 Bursal Effusion 130 cences on the undersurface of the anterior margin 9.4.2 Imaging Following Impingement Test Injection 131 Neer Neer 9.4.3 Tendinosis 131 of the acromion ( 1972). Thus it was who 9.4.4 Partial Thickness Tears 133 introduced the concept of an impingement syndrome 9.4.5 Full-Thickness Tears 134 continuum ranging from chronic bursitis and partial 9.4.5.1 Subacromial Distance 136 tears to complete tears of the supraspinatus tendon, 9.4.5.2 Peribursal Fat Plane 137 which may extend to involve other parts of the cuff 9.4.5.3 Intramuscular Cysts 137 Neer Matsen 9.4.6 Massive Tears 137 ( 1972; 1990). -

Q & A: Running Injuries Show Notes

Q & A: Running Injuries Show Notes I was told I have multiple imbalances in one leg. One was tight ankles. My question would just be how does multiple imbalances happen? Is it genetic or is it just something that happens from injury? -Johari • Imbalances can be genetic. There are many different structural anomalies found in individuals. • Most imbalances are from chronic poor posture: o Poor sitting posture. o Poor standing posture. o Asymmetries with common movement patterns. For example only crossing your left leg, or always sitting on the couch with your legs tucked under one direction. • Spot train the imbalances and asymmetries as best you can. Work toward gaining symmetry in the body. • Small changes over time will yield big results. Would love to hear about "sleeping" glutes and what can be done to reawaken them! -Britt • Most common cause is chronic sitting. • Poor posture from either standing or sitting. • The treatment is to move more. Not to just stand more (although that is better than sitting), but move more. Focus on activities that activate the posterior chain such as squats, deadlifts, and bridges. • Increase the neural input to the glutes. The more you use them, the more the neural pathways will be established and re-enforced. • Encourage everyone to address his/her glute strength as they are typically weak in most individuals. As part of cross training, implement core strengthening which will help to prevent low back pain. For more information, please refer to: http://marathontrainingacademy.com/low-back-pain http://www.thephysicaltherapyadvisor.com/2014/10/20/how-to-safely-self-treat-low-back-pain/ http://www.thephysicaltherapyadvisor.com/2014/06/30/my-top-7-tips-to-prevent-low-back-pain- while-traveling/ © 2016, The Physical Therapy Advisor www.thePhysicalTherapyAdvisor.com I have a partially torn tendon in the gluteus medius that attaches to the greater trochanter. -

The Pathomechanics of Plantar Fasciitis

Sports Med 2006; 36 (7): 585-611 REVIEW ARTICLE 0112-1642/06/0007-0585/$39.95/0 2006 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. The Pathomechanics of Plantar Fasciitis Scott C. Wearing,1 James E. Smeathers,1 Stephen R. Urry,1 Ewald M. Hennig2 and Andrew P. Hills1 1 Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, Queensland, Australia 2 Biomechanik Labor, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany Contents Abstract ....................................................................................585 1. Anatomy of the Plantar Fascia ............................................................586 1.1 Gross Anatomy of the Plantar Fascia...................................................586 1.2 Histological Anatomy of the Plantar Fascia .............................................589 1.2.1 Neuroanatomy ................................................................590 1.2.2 Microcirculation ...............................................................590 1.2.3 The Enthesis ...................................................................590 2. Mechanical Properties of the Plantar Fascia ................................................592 2.1 Structural Properties ..................................................................593 2.2 Material Properties ...................................................................593 3. Mechanical Function of the Plantar Fascia .................................................594 3.1 Quasistatic Models of Plantar Fascial Function ..........................................594 -

Piriformis Syndrome Is Overdiagnosed 11 Robert A

American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine AANEM CROSSFIRE: CONTROVERSIES IN NEUROMUSCULAR AND ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC MEDICINE Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Robert A.Werner, MD, MS Scott J. Primack, DO Willam S. Pease, MD Ernest W. Johnson, MD Lawrence R. Robinson, MD 2005 AANEM COURSE F AANEM 52ND Annual Scientific Meeting Monterey, California CROSSFIRE: Controversies in Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Robert A.Werner, MD, MS Scott J. Primack, DO Willam S. Pease, MD Ernest W. Johnson, MD Lawrence R. Robinson, MD 2005 COURSE F AANEM 52nd Annual Scientific Meeting Monterey, California AANEM Copyright © September 2005 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 421 First Avenue SW, Suite 300 East Rochester, MN 55902 PRINTED BY JOHNSON PRINTING COMPANY, INC. ii CROSSFIRE: Controversies in Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine Faculty Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Scott J. Primack, DO Assistant Clinical Professor Co-director Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Colorado Rehabilitation and Occupational Medicine Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons Denver, Colorado New York City, New York Dr. Primack completed his residency at the Rehabilitation Institute of Dr. Fishman is a specialist in low back pain and sciatica, electrodiagnosis, Chicago in 1992. He then spent 6 months with Dr. Larry Mack at the functional assessment, and cognitive rehabilitation. Over the last 20 years, University of Washington. Dr. Mack, in conjunction with the Shoulder he has lectured frequently and contributed over 55 publications. His most and Elbow Service at the University of Washington, performed some of the recent work, Relief is in the Stretch: End Back Pain Through Yoga, and the original research utilizing musculoskeletal ultrasound in order to diagnose earlier book, Back Talk, both written with Carol Ardman, were published shoulder pathology. -

Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Doctor of Physical Therapy Research Papers Physical Therapy 3-2012 Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Scott Darling St. Catherine University Hannah Finsaas St. Catherine University Andrea Johnson St. Catherine University Ashley Takekawa St. Catherine University Elizabeth Wallner St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/dpt_papers Recommended Citation Darling, Scott; Finsaas, Hannah; Johnson, Andrea; Takekawa, Ashley; and Wallner, Elizabeth. (2012). Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/dpt_papers/17 This Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Physical Therapy at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Physical Therapy Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RISK FACTORS FOR PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME by Scott Darling Hannah Finsaas Andrea Johnson Ashley Takekawa Elizabeth Wallner Doctor of Physical Therapy Program St. Catherine University March 7, 2012 Research Advisors: Assistant Professor Kristen E. Gerlach, PT, PhD Associate Professor John S. Schmitt, PT, PhD ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common source of anterior knee in pain females. PFPS has been linked to severe pain, disability, and long-term consequences such as osteoarthritis. Three main mechanisms have been proposed as possible causes of PFPS: the top-down mechanism (a result of hip weakness), the bottom-up mechanism (a result of abnormal foot structure/mobility), and factors local to the knee (related to alignment and quadriceps strength). The purpose of this study was to compare hip strength and arch structure of young females with and without PFPS in order to detect risk factors for PFPS. -

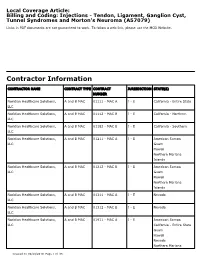

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association.