Piriformis Syndrome Is Overdiagnosed 11 Robert A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCIATICA Sciatica Describes Nerve Pain in the Leg That Is Caused by Irritation And/Or Compression of the Sciatic Nerve

ARYA AYURVEDIC PANCHAKARMA CENTRE SCIATICA Sciatica describes nerve pain in the leg that is caused by irritation and/or compression of the Sciatic nerve. Sciatica originates in the lower back, radiates deep into the buttock and travels down the leg. Sciatica is a direct result of sciatic nerve or sciatic nerve root pathology. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body with about 2cm in diameter. It arises from the L4, L5, S1, S2 and S3 spinal roots and exits the pelvis posteriorly through the greater sciatic foramen. This nerve provides direct motor function to the hamstrings, lower extremity adductors as well as indirect motor function to the calf muscles, anterior lower leg muscles and some intrinsic foot muscles. Indirectly, through its terminal branches, the sciatic nerve affects also the posterior and lateral lower leg as well as the plantar foot. So any irritation to this nerve can cause pain and/or paresthesias starting from lower back and can extend till the feet. Sciatica is a debilitating condition in which the patient experiences pain and/or paraesthe- sias in the distribution of the sciatic nerve or of an associated lumbosacral nerve root. The lifetime incidence of this condition is estimated to be up to 40 %. The condition can be- come chronic and intractable, with major socio-economic implications. ETIOLOGY • Lumbar spinal stenosis • Herniated or bulging lumbar intervertebral disc • Spondylolisthesis • Relative misalignment of one vertebra relative to another • Lumbar or pelvic muscle spasm or inflammation Copyrigh: Dr.Rohini VK, ARYA AYURVEDIC CENTRE ARYA AYURVEDIC PANCHAKARMA CENTRE • Spinal or Paraspinal masses included malignancy, epidural haematoma or epidural abscess • Lumbar degenerative disc disease • Sacroiliac joint dysfunction EPIDEMIOLOGY GENDER: There appears to be no gender predominance. -

Radiculopathy Vs. Spinal Stenosis: Evocative Electrodiagnosis Identifies the Main Pain Generator

Functional Electromyography Loren M. Fishman · Allen N. Wilkins Functional Electromyography Provocative Maneuvers in Electrodiagnosis 123 Loren M. Fishman, MD Allen N. Wilkins, MD College of Physicians & Surgeons Manhattan Physical Medicine Columbia University and Rehabilitation New York, NY 10028, USA New York, NY 10013, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-60761-019-9 e-ISBN 978-1-60761-020-5 DOI 10.1007/978-1-60761-020-5 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010935087 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. -

Brachial-Plexopathy.Pdf

Brachial Plexopathy, an overview Learning Objectives: The brachial plexus is the network of nerves that originate from cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots and eventually terminate as the named nerves that innervate the muscles and skin of the arm. Brachial plexopathies are not common in most practices, but a detailed knowledge of this plexus is important for distinguishing between brachial plexopathies, radiculopathies and mononeuropathies. It is impossible to write a paper on brachial plexopathies without addressing cervical radiculopathies and root avulsions as well. In this paper will review brachial plexus anatomy, clinical features of brachial plexopathies, differential diagnosis, specific nerve conduction techniques, appropriate protocols and case studies. The reader will gain insight to this uncommon nerve problem as well as the importance of the nerve conduction studies used to confirm the diagnosis of plexopathies. Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus: To assess the brachial plexus by localizing the lesion at the correct level, as well as the severity of the injury requires knowledge of the anatomy. An injury involves any condition that impairs the function of the brachial plexus. The plexus is derived of five roots, three trunks, two divisions, three cords, and five branches/nerves. Spinal roots join to form the spinal nerve. There are dorsal and ventral roots that emerge and carry motor and sensory fibers. Motor (efferent) carries messages from the brain and spinal cord to the peripheral nerves. This Dorsal Root Sensory (afferent) carries messages from the peripheral to the Ganglion is why spinal cord or both. A small ganglion containing cell bodies of sensory NCS’s sensory fibers lies on each posterior root. -

Piriformis Syndrome: the Literal “Pain in My Butt” Chelsea Smith, PTA

Piriformis Syndrome: the literal “pain in my butt” Chelsea Smith, PTA Aside from the monotony of day-to-day pains and annoyances, piriformis syndrome is the literal “pain in my butt” that may not go away with sending the kids to grandmas and often takes the form of sciatica. Many individuals with pain in the buttock that radiates down the leg are experiencing a form of sciatica caused by irritation of the spinal nerves in or near the lumbar spine (1). Other times though, the nerve irritation is not in the spine but further down the leg due to a pesky muscle called the piriformis, hence “piriformis syndrome”. The piriformis muscle is a flat, pyramidal-shaped muscle that originates from the front surface of the sacrum and the joint capsule of the sacroiliac joint (SI joint) and is located deep in the gluteal tissue (2). The piriformis travels through the greater sciatic foramen and attaches to the upper surface of the greater trochanter (or top of the hip bone) while the sciatic nerve runs under (and sometimes through) the piriformis muscle as it exits the pelvis. Due to this close proximity between the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve, if there is excessive tension (tightness), spasm, or inflammation of the piriformis muscle this can cause irritation to the sciatic nerve leading to symptoms of sciatica (pain down the leg) (1). Activities like sitting on hard surfaces, crouching down, walking or running for long distances, and climbing stairs can all increase symptoms (2) with the most common symptom being tenderness along the piriformis muscle (deep in the gluteal region) upon palpation. -

Sciatica and Chronic Pain

Sciatica and Chronic Pain Past, Present and Future Robert W. Baloh 123 Sciatica and Chronic Pain Robert W. Baloh Sciatica and Chronic Pain Past, Present and Future Robert W. Baloh, MD Department of Neurology University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA, USA ISBN 978-3-319-93903-2 ISBN 978-3-319-93904-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93904-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018952076 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. -

Sensory Conduction in Medial and Lateral Plantar Nerves

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.51.2.188 on 1 February 1988. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1988;51:188-191 Sensory conduction in medial and lateral plantar nerves S N PONSFORD From the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Walsgrave Hospital, Coventry, UK SUMMARY A simple and reliable method of recording medial and lateral plantar nerve sensory action potentials is described. Potentials are recorded with surface electrodes at the ankle using surface electrodes stimulating orthodromically at the sole. The normal values obtained are higher in amplitude than those obtained by the method described by Guiloff and Sherratt and are detectable in older subjects aged over 80 years. The procedure is valuable in the diagnosis of early peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritig multiplex; tarsal tunnel syndrome and in differentiation between pre and post ganglionic L5 SI lesions. The value of medial plantar sensory action potential EL53051 applied to the sole just lateral to the first meta-guest. Protected by copyright. (SAP) recording in the diagnosis of peripheral neuro- tarsal, the anode level with metatarsophalangeal joint, the pathy and investigation of root or individual nerve cathode thus overlying the first common digital nerve sub- lesions involving the leg or foot was clearly estab- serving contiguous surfaces ofthe great and second toes. For the lateral plantar, the stimulator was placed between the lished by Guiloff and Sherratt.1 However, their fourth and fifth metatarsals, the anode-again level with the method of stimulating at the big toe and recording at metatarsophalangeal joint, overlying the fourth common the ankle gives potentials of relatively small ampli- digital nerve supplying contiguous surfaces of the fourth and tude (mean amplitude 2-3 pv, range 0-8- 1). -

Ultrasound of Medial Tarsal Tunnel by Lisa Howell

Ultrasound of Medial Tarsal Tunnel by Lisa Howell Medial Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Medial Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome (Posterior Tibial Neuralgia) is a compression neuropathy Occurs when Posterior Tibial Nerve (PTN) and / or its branches are entrapped within Tarsal Tunnel of Medial ankle Proximal syndrome compression main trunk of PTN, affects entire foot Distal syndrome compression of divisional branches of PTN Medial TTS: -More complex than carpal tunnel syndrome in wrist -Diagnosis and treatment of TTS depends on cause, and severity -Pain typically radiates down medial ankle to heel and/or plantar aspect of foot -Symptoms occur whilst standing, during exercise, and at night when patient is at rest [Ref: 1, 6] Anatomy Medial Ankle Medial Tarsal Tunnel MTT Fibro-osseous tunnel of medial ankle, posterior and inferior to medial malleolus (MM) Tendons of medial ankle Tibialis posterior (PTT), Flexor digitorum longus (FDL), and Flexor hallucis longus (FHL) Ligaments of medial ankle Deltoid ligament is fan shaped, and originates at MM It is divided into a deep and superficial layers Deep layer : Anterior tibiotalar lig, and Posterior tibiotalar lig Superficial layer: Tibionavicular lig, Tibiospring lig, and Tibiocalcaneal lig Neurovascular bundle Posterior tibial nerve (PTN), Posterior tibial artery (PTA), and Posterior tibial veins (PTV) [Ref : 1,6 ] Anatomy of PTN Posterior Tibial Nerve (PTN) branch of Sciatic nerve divides at medial ankle into three branches : ● Medial Calcaneal Nerve ● Medial Plantar Nerve ● Lateral Plantar Nerve Proximal Medial Tarsal Tunnel Flexor Retinaculum (FR) forms the roof of prox MTT Medial Calcaneal nerve (MCN) first branch of PTN MCN superficial to Abductor Hallucis muscle (AHM) Innervates posterior medial part of calcaneus, and posterior fat pad of foot Distal Medial Tarsal Tunnel Lateral Plantar nerve (LPN), and Medial Plantar nerve (MPN) are the terminal branches of PTN [Ref: 1,6] Frank.H.Netter, MD. -

Lumbosacral Plexus Entrapment Syndrome. Part One: a Common Yet Little-Known Cause of Chronic Pelvic and Lower Extremity Pain

3-A Running head: ANAESTHESIA, PAIN & INTENSIVE CARE www.apicareonline.com ORIGINAL ARTICLE Lumbosacral plexus entrapment syndrome. Part one: A common yet little-known cause of chronic pelvic and lower extremity pain Kjetil Larsen, CES, George C. Chang Chien, D O2 ABSTRACT Corrective exercise specialist, Training & Rehabilitation, Oslo Lumbosacral plexus entrapment syndrome (LPES) is a little-known but common cause Norway of chronic lumbopelvic and lower extremity pain. The lumbar plexus, including the 2 Director of pain management, lumbosacral tunks emerge through the fibers of the psoas major, and the proximal Ventura County Medical Center, sciatic nerve beneath the piriformis muscles. Severe weakness of these muscles may Ventura, CA 93003, USA. lead to entrapment plexopathy, resulting in diffuse and non-specific pain patterns Correspondence: Kjetil Larsen, CES, Corrective throughout the lumbopelvic complex and lower extremities (LPLE), easily mimicking Exercise Specialist, Training & other diagnoses and is therefore likely to mislead the interpreting clinician. It is a Rehabilitation, Oslo Norway; pathology very similar to that of thoracic outlet syndrome, but for the lower body. This Kjetil@trainingandrehabilitation. two part manuscript series was written in an attempt to demonstrate the existence, com; pathophysiology, diagnostic protocol as well as interventional strategy for LPES, and Tel.: +47 975 45 192 its efficacy. Received: 23 November 2018, Reviewed & Accepted: 28 Key words: Pelvic girdle; Pain, Pelvic girdle; Lumbosacral plexus entrapment syndrome; February 2019 Piriformis syndrome; Nerve entrapment; Double-crush; Pain, Chronic; Fibromyalgia Citation: Larsen K, Chien GCC. Lumbosacral plexus entrapment syndrome. Part one: A common yet little-known cause of chronic pelvic and lower extremity pain. -

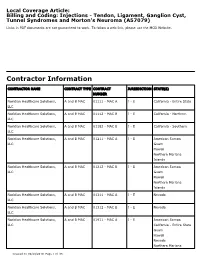

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: a Still Challenge Condition

Rev Bras Neurol. 55(1):12-17, 2019 TARSAL TUNNEL SYNDROME: A STILL CHALLENGE CONDITION SÍNDROME DO TÚNEL DO TARSO: UMA CONDIÇÃO AINDA DESAFIADORA Celmir de Oliveira Vilaça1,2, Bruno Pessoa3, Janaína de Moraes Silva4, Victor Hugo Bastos5, Diandra Martins5, Silmar Teixeira6, Victor Marinho6, Rossano Fiorelli7, Vanessa de Albuquerque Dinoa8; Marco Orsini7, 9 ABSTRACT RESUMO Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a rare, under diagnosed and often confu- A Síndrome do túnel do tarso é uma rara e subdiagnosticada neuro- sed neuropathy with other clinical entities. There is a lack of popula- patia geralmente confundida com outras entidades clínicas. Há falta tion studies on this disease. Herein, we performed a non-systematic de estudos populacionais sobre a doença. Assim sendo, realizamos review of articles between January 1992 and February 2018. Althou- uma revisão da literatura de artigos entre Janeiro de 1992 e fevereiro gh with a less complex anatomy comparing to the carpal tunnel, the de 2018. Apesar de possuir uma anatomia de menor complexidade tarsal tunnel is source of pain and some other conditions. Treatment comparada ao túnel do carpo, o túnel do tarso é origem de dor e involves conservative measures such as analgesics and physical the- algumas outras condições. O tratamento envolve medidas conserva- rapy rehabilitation or surgical procedures in case of conservative doras como analgésicos e terapia de reabilitação ou procedimentos treatment failure. Randomized control studies are lack and manda- cirúrgicos, em caso de falha do tratamento conservador. Estudos ran- tory for uncover the best modality of treatment for this condition. domizados são escassos e necessários para descoberta da melhor modalidade de tratamento desta condição. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

MICHAEL J. BAKER, D.P.M. JASON D. GRAY, D.P.M. GREGORY W. BOAKE, D.P.M JESSICA R TAULMAN, D.P.M BFS BUSINESS OFFICE P O BOX 330. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Fortville, IN 46040-0330 Tel 317.863.2556 Fax 317.203.0420 Tarsal tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy (pressure on nerve) of the tibial nerve as it courses through the inside COMMUNITY FOOT & ANKLE CENTER aspect of the foot and ankle. 1221 Medical Arts Blvd. Anderson, IN 46011 Tel 765.641.0001 Symptoms. Pain, numbness, burning and electrical sensations Fax 765.641.0003 may occur along the course of the nerve, which includes the EAST FOOT & inside of the ankle, heel, arch and bottom of foot. Symptoms are ANKLE CENTER usually worsened with increased activity such as walking or 161B Washington Point Dr. Indianapolis, IN 46229 exercise. Prolonged standing in one place may also be an Tel 317.898.6624 aggravating factor. Fax 317.898.6636 FOOT & ANKLE AT WESTVIEW HOSPITAL 3520 Guion Rd., Ste 102 Indianapolis, IN 46222 Tel 317.920.3240 Fax 317.920.3243 MARION FOOT CENTER 330 N. Wabash Ave, Ste 460A Marion, IN 46952 Tel 765.664.1413 Fax 765.965.6530 BAKER FOOT SOLUTIONS SATILLITE FOOT CLINICS BROWNSBURG Tel 317.920.3240 Causes. There are a variety of factors that may cause tarsal Fax 317.920.3243 tunnel syndrome. These may include repetitive stress with GEIST FAMILY PRACTICE activities, flat feet, and excess weight. Additionally, any lesion Tel 317.898.6624 Fax 317.898.6636 that occupies space within the tarsal tunnel region may cause NEW CASTLE pressure on the nerve and subsequent symptoms. -

The Efficacy and Safety of Gabapentin in Carpal Tunnel Patients: Open Label Trial

Original Article The efficacy and safety of gabapentin in carpal tunnel patients: Open label trial A. Kemal Erdemoglu Ayhan Varlibas, Kirikkale University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neurology, Kirikkale, 07100, Turkey Abstract Background: Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment neuropathy caused by median nerve compression at the wrist. It results in loss of considerable man days and the effectiveness the various treatment modalities are still debated. Aim: To study the efficacy of gabapentin in patients with CTS. The study aim is to investigate the efficacy of gabapentin in patients with CTS patients who were refractory to the other conservative measures or unwilling for the surgical procedure. Materials and Methods: Forty one patients diagnosed as idiopathic CTS were included in the study. Patients were assessed with symptom severity scale (SSS) and functional status scale (FSS) scores of Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire (BCTQ) before and at 1, 3, and 6 months of the treatment. Response to therapy was determined by using SSS and FSS scores of Address for correspondence: BCTQ. Results: The median dosage of gabapentin was 1800 mg/daily. Side effects Dr. A. Kemal Erdemoglu were mild and transient. There was a statistically significant difference in both symptom Kirikkale University, Faculty of Medicine, SSS and FSS scores between before and after treatment in patient groups at the end Department of Neurology, of six months (P < 0.001). According to grading the changes in subscales of BCTQ, Kirikkale, 07100, TURKEY. of 41 patients, 34.1 and 29.3 had a ≥ 40% decrease in SSS and FSS, respectively. E-mail: [email protected] Conclusion: Gabapentin was found to be partially effective and safe in symptomatic treatment of CTS patients.