Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-Growth Douglas-Fir-Western Hemlock Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar Youran Fan1,2, Keith Woeste1,2, Daniel Cassens1, Charles Michler1,2, Daniel Szymanski3, and Richard Meilan1,2 1Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, 2Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, and 3Department of Agronomy; Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract Materials and Methods When “Curly Aspen” (Populus canescens) was first Preliminary Results characterized in the early 1940’s[1], it attracted the attention from the wood-products industry because Genetically engineer commercially 1) Histological sections reveal that “Curly Aspen” has strong “Curly Aspen” produces an attractive veneer as a important trees to form figure. ray flecks (Fig. 10) but this is not likely to be responsible result of its figured wood. Birdseye, fiddleback and for the figure seen. quilt are other examples of figured wood that are 2) Of the 15 SSR primer pairs[6, 7, 8] tested, three have been commercially important[2]. These unusual grain shown to be polymorphic. Others are now being tested. patterns result from changes in cell orientation in Figure 6. Pollen collection. Branches of Figure 7. Pollination. Branches Ultimately, our genetic fingerprinting technique will allow “Curly Aspen” were “forced” to shed collected from a female P. alba us to distinguish “Curly Aspen” from other genotypes. the xylem. Although 50 years have passed since Figure 1. Birdseye in maple. pollen under controlled conditions. growing at Iowa State University’s finding “Curly Aspen”, there is still some question Rotary cut, three-piece book McNay Farm (south of Lucas, IA). 3) 17 jars of female P. alba branches have been pollinated match (origin: North America). -

Bromfield Garden Plant List - 2009

BROMFIELD GARDEN PLANT LIST - 2009 BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME Acer circinatum vine maple Achillea millefolium yarrow Achillea millefolium 'Judity' yarrow 'Judity' Achillea millefolium 'La Luna' yarrow 'La Luna' Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' yarrow 'Paprika' Achillea millefolium 'Salmon' yarrow 'Salmon' Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' yarrow 'Sonoma Coast' Aesculus californica California buckeye Aquilegia formosa western columbine Arctostaphylos 'Pacific Mist' manzanita 'Pacific Mist' Arctostaphylos hookeri 'Ken Taylor' manzanita 'Ken Taylor' Aristolochia californica California pipevine Armeria maritima sea pink Artemisia pycnocephala sandhill sage Asarum caudatum wild ginger Aster chilensis California aster Aster chilensis dwarf California aster Baccharis pilularis 'Twin Peaks' dwarf coyote brush 'Twin Peaks' Berberis aquifolium var repens creeping Oregon-grape Berberis nervosa dwarf Oregon-grape Blechnum spicant deer fern Calycanthus occidentalis spice bush Camissonia cheiranthifolia beach evening primrose Carex tumulicola Berkeley sedge Carpenteria californica bush anenome Ceanothus 'Concha' wild lilac 'Concha' Ceanothus 'Tilden Park' wild lilac 'Tilden Park' Cercis occidentalis western redbud Cercocarpus betuloides mountain mahogany Clematis lasiantha chaparral clematis Cornus sericea creek dogwood Corylus cornuta western hazelnut Dicentra formosa western bleeding heart Dichondra donneliana pony's foot Dryopteris arguta coastal wood fern Dudleya caespitosa sea lettuce Dudleya farinosa bluff lettuce Dudleya pulverulenta chalk liveforever -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

GIS Handbook Appendices

Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Appendix D Cooperating Agency Codes The following table lists the aerial survey cooperating agencies and codes to be used in the agency1, agency2, agency3 fields of the flown/not flown coverages. The contents of this list is available in digital form (.dbf) at the following website: http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/publications/id/id_guidelines.html 28 Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Code Agency Name AFC Alabama Forestry Commission ADNR Alaska Department of Natural Resources AZFH Arizona Forest Health Program, University of Arizona AZS Arizona State Land Department ARFC Arkansas Forestry Commission CDF California Department of Forestry CSFS Colorado State Forest Service CTAES Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station DEDA Delaware Department of Agriculture FDOF Florida Division of Forestry FTA Fort Apache Indian Reservation GFC Georgia Forestry Commission HOA Hopi Indian Reservation IDL Idaho Department of Lands INDNR Indiana Department of Natural Resources IADNR Iowa Department of Natural Resources KDF Kentucky Division of Forestry LDAF Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry MEFS Maine Forest Service MDDA Maryland Department of Agriculture MADCR Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation MIDNR Michigan Department of Natural Resources MNDNR Minnesota Department of Natural Resources MFC Mississippi Forestry Commission MODC Missouri Department of Conservation NAO Navajo Area Indian Reservation NDCNR Nevada Department of Conservation -

Volume 12 - Number 1 March 2005

Utah Lepidopterist Bulletin of the Utah Lepidopterists' Society Volume 12 - Number 1 March 2005 Extreme Southwest Utah Could See Iridescent Greenish-blue Flashes A Little Bit More Frequently by Col. Clyde F. Gillette Battus philenor (blue pipevine swallowtail) flies in the southern two- thirds of Arizona; in the Grand Canyon (especially at such places as Phantom Ranch 8/25 and Indian Gardens 12/38) and at its rims [(N) 23/75 and (S) 21/69]; in the low valleys of Clark Co., Nevada; and infrequently along the Meadow Valley Wash 7/23 which parallels the Utah/Nevada border in Lincoln Co., Nevada. Since this beautiful butterfly occasionally flies to the west, southwest, and south of Utah's southwest corner, one might expect it to turn up now and then in Utah's Mojave Desert physiographic subsection of the Basin and Range province on the lower southwest slopes of the Beaver Dam Mountains, Battus philenor Blue Pipevine Swallowtail Photo courtesy of Randy L. Emmitt www.rlephoto.com or sporadically fly up the "Dixie Corridor" along the lower Virgin River Valley. Even though both of these Lower Sonoran life zone areas reasons why philenor is not a habitual pipevine species.) Arizona's of Utah offer potentially suitable, resident of Utah's Dixie. But I think interesting plant is Aristolochia "nearby" living conditions for Bat. there is basically only one, and that is watsonii (indianroot pipevine), which phi. philenor, such movements have a complete lack of its larval has alternate leaves shaped like a not often taken place. Or, more foodplants in the region. -

Plants That Provide Seeds and Berries

Native Plants that Provide Seeds and Berries Abies amabilis Pacific Silver Fir An attractive conifer with short dark green needles. Tolerant of shade. Squirrels and other rodents extract seeds from the large cones. Abies grandis Grand Fir Abies grandis is a tall, straight tree with short, dense branches. Grouse, nuthatches, chickadees, grosbeaks, finches, crossbills feed on the fir seeds. Sapsuckers and woodpeckers feed on the foliage. Pine white butterfly larvae eat the leaves. Acer circinatum Vine Maple Tall, erect, multi-trunked shrub or small tree with sprawling branches. Birds that eat the seeds include grosbeaks, woodpeckers, nuthatches, finches, quail, and grouse. A larvae plant for the brown tissue moth and the Polyphemus moth. A good nectar source for bees. Deer, mountain beavers, and other beavers eat the twigs and wood. Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf Maple A tree with a large, often multi-stemmed trunk and a loose, broad crown of large leaves. The rotting limbs provide a food source for insect-eating birds such as grouse, grosbeaks, kinglets, siskins, vireos, warblers, sapsuckers, woodpeckers, nuthatches, song sparrows, finches, and quail. Acer macrophyllum is a good nectar source for swallowtail butterfly larvae and bees. Deer, muskrats, and beaver eat the wood and twigs. Achillea millefolium Yarrow Aromatic herb with delicate fern-like leaves and flat-topped clusters of white flowers. Arbutus menziesii Madrone An attractive broadleaf evergreen with a twisting reddish trunk and irregular branches with an overall rounded outline. The fruit is eaten by band-tailed pigeons, quail, flickers, varied thrushes, waxwings, evening grosbeaks, mourning doves, and robins. The flowers are pollinated by spring azure butterflies and bees. -

Comparison of Oak and Sugar Maple Distribution and Regeneration in Central Illinois Upland Oak Forests

COmparisON OF OaK AND Sugar MAPLE DistriBUTION AND REGENEratiON IN CEntral ILLINOIS UPLAND OaK FOREsts Peter J. Frey and Scott J. Meiners1 Abstract.—Changes in disturbance frequencies, habitat fragmentation, and other biotic pressures are allowing sugar maple (Acer saccharum) to displace oak (Quercus spp.) in the upland forest understory. The displacement of oaks by sugar maples represents a major management concern throughout the region. We collected seedling microhabitat data from five upland oak forest sites in central Illinois, each differing in age class or silvicultural treatment to determine whether oaks and maples differed in their microhabitat responses to environmental changes. Maples were overall more prevalent in mesic slope and aspect positions. Oaks were associated with lower stand basal area. Both oaks and maples showed significant habitat partitioning, and environmental relationships were consistent across sites. Results suggest that management intensity for oak in upland forests could be based on landscape position. Maple expansion may be reduced by concentrating mechanical treatments in expected areas of maple colonization, while using prescribed fire throughout stands to promote oak regeneration. INTRODUCTION Historically, white oak (Quercus alba) dominated much of the midwestern and eastern U.S. hardwood forests (Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Franklin et al. 1993). Oak is classified as an early successional forest species, and many researchers agree that oak populations were maintained by Native American or lightning-initiated fires (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Hutchinson et al. 2008, Moser et al. 2006, Nowacki and Abrams 2008, Ruffner and Groninger 2006, Shumway et al. 2001). These periodic low to moderate surface fires favored the ecophysiological attributes of oak over those of fire-sensitive, shade-tolerant tree species, thereby continually resetting succession and allowing oaks and other shade-intolerant species to persist in both the canopy and understory (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Crow 1988, Franklin et al. -

Butterflies and Moths of Cibola County, New Mexico, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers. -

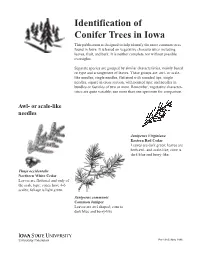

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable Mesic Forest (RMF): Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forests are most occurrences of RMF diverse forests in central and eastern in Massachusetts are west Massachusetts where conditions, of the Connecticut River including nutrient richness, support Valley. The presence of Northern Hardwood species mixed with multiple species of species of Oak - Hickory Forests; hickories and oaks in SMOH is a main The herbaceous layer varies from sparse difference between these to intermittent, with sparse spring two types. Broad-leaved ephemerals that may include bloodroot or Woodland-sedge is close trout-lily. Later occurring species may to being an indicator of include wild geranium, herb Robert, wild SMOH. RMF is Rock outcrops in the spring in Sugar Maple - licorice, maidenhair fern, bottlebrush Oak - Hickory Forest area. Photo: Patricia characterized by very Swain, NHESP. grass, and white wood aster. Broad- dense herbaceous growth of spring leaved, semi-evergreen broad-leaved ephemerals; SMOH shares some of the Description: Sugar Maple - Oak - woodland-sedge is close to an indicator of species but with fewer individuals of Hickory Forests occur in or east of the the community. Witch hazel, hepaticas, fewer species. SMOH has evergreen Connecticut River Valley in and wild oats usually occur in transitions ferns, Christmas fern and wood ferns, that Massachusetts. They are associated with to surrounding forest types. RMF lack. Oak - Hickory Forests and outcrops of circumneutral rock and slopes Dry, Rich Oak Forests/Woodlands lack below them that have more nutrients than abundant sugar maple, basswood, and are available in the surrounding forest. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value.