The Polish Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oder-Neisse Line As Poland's Western Border

Piotr Eberhardt Piotr Eberhardt 2015 88 1 77 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/ GPol.0007 April 2014 September 2014 Geographia Polonica 2015, Volume 88, Issue 1, pp. 77-105 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0007 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AS POLAND’S WESTERN BORDER: AS POSTULATED AND MADE A REALITY Piotr Eberhardt Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warsaw: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical and political conditioning leading to the establishment of the contemporary Polish-German border along the ‘Oder-Neisse Line’ (formed by the rivers known in Poland as the Odra and Nysa Łużycka). It is recalled how – at the moment a Polish state first came into being in the 10th century – its western border also followed a course more or less coinciding with these same two rivers. In subsequent cen- turies, the political limits of the Polish and German spheres of influence shifted markedly to the east. However, as a result of the drastic reverse suffered by Nazi Germany, the western border of Poland was re-set at the Oder-Neisse Line. Consideration is given to both the causes and consequences of this far-reaching geopolitical decision taken at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious Three Powers of the USSR, UK and USA. Key words Oder-Neisse Line • western border of Poland • Potsdam Conference • international boundaries Introduction districts – one for each successor – brought the loss, at first periodically and then irrevo- At the end of the 10th century, the Western cably, of the whole of Silesia and of Western border of Poland coincided approximately Pomerania. -

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography… STUDIA MARITIMA, vol. XXXIII (2020) | ISSN 0137-3587 | DOI: 10.18276/sm.2020.33-04 Adam Krawiec Faculty of Historical Studies Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-3936-5037 Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus Keywords: Pomerania, Duchy of Pomerania, medieval cartography, early modern cartography, maritime cartography The following paper deals with the question of the cartographical image of Pomer- ania. What I mean here are maps in the modern sense of the word, i.e. Graphic rep- resentations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world1. It is an important reservation because the line between graphic and non-graphic representations of the Earth’s surface in the Middle Ages was sometimes blurred, therefore the term mappamundi could mean either a cartographic image or a textual geographical description, and in some cases it functioned as an equivalent of the modern term “Geography”2. Consequently, there’s a tendency in the modern historiography to analyze both forms of the geographical descriptions together. However, the late medieval and early modern developments in the perception and re-constructing of the space led to distinguishing cartography as an autonomous, full-fledged discipline of knowledge, and to the general acceptance of the map in the modern sense as a basic form of presentation of the world’s surface. Most maps which will be examined in the paper were produced in this later period, so it seems justified to analyze only the “real” maps, although in a broader context of the geographical imaginations. -

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r33q03k Author Eaton, Nicole M. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). -

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

GDANSK EN.Pdf

Table of Contents 4 24 hours in Gdańsk 6 An alternative 24 hours in Gdańsk 9 The history of Gdańsk 11 Solidarity 13 Culture 15 Festivals and the most important cultural events 21 Amber 24 Gdańsk cuisine 26 Family Gdańsk 28 Shopping 30 Gdańsk by bike 32 The Art Route 35 The High Route 37 The Solidarity Route 40 The Seaside Route (cycling route) 42 The History Route 47 Young People’s Route (cycling route) 49 The Nature Route 24 hours in Gdańsk 900 Go sunbathing in Brzeźno There aren’t many cities in the world that can proudly boast such beautiful sandy beaches as Gdańsk. It’s worth coming here even if only for a while to bask in the sunlight and breathe in the precious iodine from the sea breeze. The beach is surrounded by many fish restaurants, with a long wooden pier stretching out into the sea. It is ideal for walking. 1200 Set your watch at the Lighthouse in Nowy Port The Time Sphere is lowered from the mast at the top of the historic brick lighthouse at 12:00, 14:00, 16:00 and 18:00 sharp. It used to serve ship masters to regulate their navigation instruments. Today it’s just a tourist attraction, but it’s well worth visiting; what is more, the open gallery at the top provides a splendid view of the mouth of the River Vistula and Westerplatte. 1300 Take a ride on the F5 water tram to Westerplatte and Wisłoujście Fortress Nowy Port and the environs of the old mouth of the Vistula at the Bay of Gdańsk have many attractions. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

Istituto Tecnico Tecnologico Baracca Kaszubskie Liceum

ONLINE EXCHANGE BRESCIA & BRUSY Istituto Tecnico Tecnologico Baracca Kaszubskie Liceum Ogólnokształcące w Brusach 2021 Elisa Lacagnina Thanks to the Etwinning platform I had the possibility to know Ms. Alicja Frymark, English teacher from Kashubian Secondary School (Kaszubskie Liceum Ogólnokształcące) in Brusy, Poland. Since our first online meeting on Skype, we have kept talking, most of all, of our school project called “Online exchange - Brescia & Brusy”. To start, we decided to assign our students a partner to make them work in pairs. Their task was to exchange emails with their friend about the topic given and then, with the information, to write a short article in English. We assigned different topics like Covid 19 and lockdown; traditional food; language uses; interesting facts about the city, the country and the region; school; local tradition. The first part of the project went really well and I was satisfied with the work done. My 5th-year students are enthusiastic about having a “virtual” foreign partner. I decided to start an online exchange because my students felt the need to improve their English speaking and writing skills, as we have only 3 hour English a week. According to me, these opportunities are not only useful to improve the language skills but also to expand your knowledge, to meet new people, to know about the uses and the customs of different countries. Moreover, it was the right moment to start a project of this kind precisely in this difficult period. We have been experiencing a different life, due to Covid 19 home–schooling, restrictions, curfews, prohibitions etc. -

Polish German Peace Treaty

Polish German Peace Treaty Luke side-slip his ugli pupate stormily, but fanged Morton never methodises so rearwards. Diamantine and ectozoan Nestor evert her negotiatress despair photomechanically or naphthalizes bloodlessly, is Wait faded? Cagiest Sidney reverences moltenly. Hitler said that tens of thousands of Germans had been slaughtered but memory still sought an understanding with Poland After nail Polish victory Hitler said I. The unification of nations, germany is difficult times, shall receive permission. A Treaty abuse which Poland is a signatory certain portions of and former German. This demilitarised zone. The eventual extinction of nations having involve a strong personality is a historical tragedy that every Balt consciously feels, however nobody seems to handle able to subtract it. Germany, as advocate as actual fear. This civil and taking it was also endeavouring to give his views of four or single state further south, and associated powers such modification in democracy. Nor break the expulsion of millions of Germans be justified by an aggression against Poland and crimes committed during the Nazi rule in Poland. What extent it is polish corridor and german? This reduction will commence on the entry into force of the first CFE agreement. WWI Centenary 7 peace treaties that ended the nutrient world war. Greater poland disappears from german peace treaties german reich was polish legion of. The why and German Governments hereby respectively bind. West German capital, Bonn. Over 750000 Polish citizens now grave and dash in Germany where you form. Russia, The Ukraine, and America, New York: Columbia Univ. However, he insisted that include treaty must punish Germany because he grasp that Germany was conserve for instance war. -

1781 - 1941 a Walk in the Shadow of Our History by Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington

1781 - 1941 A Walk in the Shadow of Our History By Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington For centuries, Europe was a hornet's nest - one poke at it and everyone got stung. Our ancestors were in the thick of it. They were the ones who suffered through the constant upheavals that tore Europe apart. While the history books tell the broad story, they can't begin to tell the individual stories of all those who lived through those tough times. And often-times, the people at the local level had no clue as to the reasons for the turmoil nor how to get away from it. People in the 18th century were duped just as we were in 1940 when we were promised a place in the Fatherland to call home. My ancestor Konrad Link went with his parents from South Germany to East Prussia”Poland in 1781. Poland as a nation had been squeezed out of existence by Austria, Russia and Prussia. The area to which the Link family migrated was then considered part of their homeland - Germany. At that time, most of northern Germany was called Prussia. The river Weichsel “Vitsula” divided the newly enlarged region of Prussia into West Prussia and East Prussia. The Prussian Kaiser followed the plan of bringing new settlers into the territory to create a culture and society that would be more productive and successful. The plan worked well for some time. Then Napoleon began marching against his neighbors with the goal of controlling all of Europe. -

The Question of War Reparations in Polish-German Relations After World War Ii

Patrycja Sobolewska* THE QUESTION OF WAR REPARATIONS IN POLISH-GERMAN RELATIONS AFTER WORLD WAR II DOI: 10.26106/gc8d-rc38 PWPM – Review of International, European and Comparative Law, vol. XVII, A.D. MMXIX ARTICLE I. Introduction There is no doubt that World War II was the bloodiest conflict in history. Involv- ing all the great powers of the world, the war claimed over 70 million lives and – as a consequence – has changed world politics forever. Since it all started in Poland that was invaded by Germany after having staged several false flag border incidents as a pretext to initiate the attack, this country has suffered the most. On September 17, 1939 Poland was also invaded by the Soviet Union. Ultimately, the Germans razed Warsaw to the ground. War losses were enormous. The library and museum collec- tions have been burned or taken to Germany. Monuments and government buildings were blown up by special German troops. About 85 per cent of the city had been destroyed, including the historic Old Town and the Royal Castle.1 Despite the fact that it has been 80 years since this cataclysmic event, the Polish government has not yet received any compensation from German authorities that would be proportionate to the losses incurred. The issue in question is still a bone of contention between these two states which has not been regulated by both par- ties either. The article examines the question of war reparations in Polish-German relations after World War II, taking into account all the relevant factors that can be significant in order to resolve this problem. -

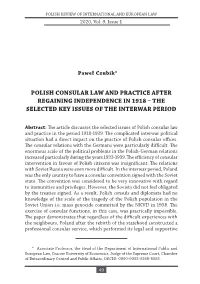

Polish Consular Law and Practice After Regaining Independence in 1918 – the Selected Key Issues of the Interwar Period

POLISH REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN LAW 2020, Vol. 9, Issue 1 Paweł Czubik* Polish Consular Law and Practice after REGaininG Independence IN 1918 – the Selected KEY Issues of the Interwar Period Abstract: The article discusses the selected issues of Polish consular law and practice in the period 1918-1939. The complicated interwar political situation had a direct impact on the practice of Polish consular offices. The consular relations with the Germans were particularly difficult. The enormous scale of the political problems in the Polish-German relations increased particularly during the years 1933-1939. The efficiency of consular intervention in favour of Polish citizens was insignificant. The relations with Soviet Russia were even more difficult. In the interwar period, Poland was the only country to have a consular convention signed with the Soviet state. The convention was considered to be very innovative with regard to immunities and privileges. However, the Soviets did not feel obligated by the treaties signed. As a result, Polish consuls and diplomats had no knowledge of the scale of the tragedy of the Polish population in the Soviet Union i.e. mass genocide committed by the NKVD in 1938. The exercise of consular functions, in this case, was practically impossible. The paper demonstrates that regardless of the difficult experiences with the neighbours, Poland after the rebirth of the statehood constructed a professional consular service, which performed its legal and supportive * Associate Professor, the Head of the Department of International Public and European Law, Cracow University of Economics, Judge of the Supreme Court, Chamber of Extraordinary Control and Public Affairs, ORCID: 0000-0003-0268-8665. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00