FORUM 5 Rapporteur's Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'New Society' and the Philippine Labour Export Policy (1972-1986)

EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIppINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIPPINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) Mark Macaa Kyushu University Abstract: The ‘overseas Filipino workers’ (OFWs) are the largest source of US dollar income in the Philippines. These state-sponsored labour migrations have resulted in an exodus of workers and professionals that now amounts to approximately 10% of the entire country’s population. From a temporary and seasonal employment strategy during the early American colonial period, labour export has become a cornerstone of the country’s development policy. This was institutionalised under the Marcos regime (1965-1986), and especially in the early years of the martial law period (1972-81), and maintained by successive governments thereafter. Within this context, this paper investigates the relationship between Marcos’ ‘New Society’ agenda, the globalization of migrant labour, and state sponsorship of labour exports. In particular, it analyses the significance of attempts made to deploy education policy and educational institutions to facilitate the state’s labour export drive. Evidence analyzed in this paper suggests that sweeping reforms covering curricular policies, education governance and funding were implemented, ostensibly in support of national development. However, these measures ultimately did little to boost domestic economic development. Instead, they set the stage for the education system to continue training and certifying Filipino skilled labour for global export – a pattern that has continued to this day. Keywords: migration, labour export, education reforms, Ferdinand Marcos, New Society Introduction This paper extends a historical analysis begun with an investigation of early Filipino labour migration to the US and its role in addressing widespread poverty and unemployment (Maca, 2017). -

THE POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA the POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA Linda K

THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA Linda K. Richter 2018 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880163 (PDF) 9780824880170 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgments vi Abbreviations Used in Text viii 1. The Politics of Tourism: An Overview 1 2. About Face: The Political Evolution of Chinese Tourism Policy 25 3. The Philippines: The Politicization of Tourism 57 4. Thailand: Where Tourism and Politics Make Strange Bedfellows 92 5. Indian Tourism: Pluralist Policies in a Federal System 115 6. Creating Tourist “Meccas” in Praetorian States: Case Studies of Pakistan and Bangladesh 153 Pakistan 153 Bangladesh 171 7. Sri Lanka and the Maldives: Islands in Transition 178 Sri Lanka 178 The Maldives 186 8. Nepal and Bhutan: Two Approaches to Shangri-La 190 Nepal 190 Bhutan 199 9. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. I. The sign or "target" for pages apparcntly lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagets)". II' it was possible to obtain the missing pagers) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrigh ted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, ctc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again vbcginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

SANCHEZ Final Defense Draft May 8

LET THE PEOPLE SPEAK: SOLIDARITY CULTURE AND THE MAKING OF A TRANSNATIONAL OPPOSITION TO THE MARCOS DICTATORSHIP, 1972-1986 BY MARK JOHN SANCHEZ DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History with a minor in Asian American Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Augusto Espiritu, Chair Professor Antoinette Burton Associate Professor Jose Bernard Capino Professor Kristin Hoganson Abstract This dissertation attempts to understand pro-democratic activism in ways that do not solely revolve around public protest. In the case of anti-authoritarian mobilizations in the Philippines, the conversation is often dominated by the EDSA "People Power" protests of 1986. This project discusses the longer histories of protest that made such a remarkable mobilization possible. A focus on these often-sidelined histories allows a focus on unacknowledged labor within social movement building, the confrontation between transnational and local impulses in political organizing, and also the democratic dreams that some groups dared to pursue when it was most dangerous to do so. Overall, this project is a history of the transnational opposition to the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines. It specifically examines the interactions among Asian American, European solidarity, and Filipino grassroots activists. I argue that these collaborations, which had grassroots activists and political detainees at their center, produced a movement culture that guided how participating activists approached their engagements with international institutions. Anti-Marcos activists understood that their material realities necessitated an engagement with institutions more known to them for their colonial and Cold War legacies such as the press, education, human rights, international law, and religion. -

The Filipinos Protest Over Hero's

Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics & Strategic Studies, Vol. 46 (1) (July 2019): 1-26 @ Centre For Policy and Global Governance (GAP), UKM; ISSN 2180-0251 (electronic), 0126-5644 (paper) NORIZAN Kadir Universiti Sains Malaysia REMEMBERING AND FORGETTING THE MEMORIES OF VIOLENCE: THE FILIPINOS PROTEST OVER HERO’S INTERMENT FOR MARCOS, 2016-2017 This article examines the divergence in social memory about Ferdinand Marcos’ rule into two types of historical narratives following the announcement made by President Duterte in 2016 to bury the Marcos’ remains in the Heroes’ Cemetery or Libingan ng mga Bayani. The historical narratives were divided into two major school of thoughts which comprised the national narrative that was propagated by President Rodrigo Duterte and the opposition narrative advocated by the victims and relatives of Marcos’ human rights violence. The protests and demonstrations took place from 2016 until 2017, before and after the interment of the remains through various forms and methods including street protests and internet activism. Thus, this study shows that the changing of political ideologies has changed the national narrative since the memories of violence during the Marcos’ regime are gradually lost from the social memory of the society. The proponent of President Duterte and Marcos’ legacy demand justice for the late President Marcos for his contributions to the country, while those who oppose President Duterte as well as the victims of Marcos’ cruelty, try to revive the memory about Marcos’ spate of violence. Their demands are voiced through their protests over Hero’s burial for Marcos. Keywords: Memories Of Violence, Interment, Dictatorship, Social Memory, Historical Amnesia. -

The City As Illusion and Promise

Ateneo de Manila University Archīum Ateneo Philosophy Department Faculty Publications Philosophy Department 10-2019 The City as Illusion and Promise Remmon E. Barbaza Follow this and additional works at: https://archium.ateneo.edu/philo-faculty-pubs Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Making Sense of the City Making Sense of the City REMMON E. BARBAZA Editor Ateneo de Manila University Press Ateneo de Manila University Press Bellarmine Hall, ADMU Campus Contents Loyola Heights, Katipunan Avenue Quezon City, Philippines Tel.: (632) 426-59-84 / Fax (632) 426-59-09 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ateneopress.org © 2019 by Ateneo de Manila University and Remmon E. Barbaza Copyright for each essay remains with the individual authors. Preface vii Cover design by Jan-Daniel S. Belmonte Remmon E. Barbaza Cover photograph by Remmon E. Barbaza Book design by Paolo Tiausas Great Transformations 1 The Political Economy of City-Building Megaprojects All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in the Manila Peri-urban Periphery stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or Jerik Cruz otherwise, without the written permission of the Publisher. Struggling for Public Spaces 41 The Political Significance of Manila’s The National Library of the Philippines CIP Data Segregated Urban Landscape Recommended entry: Lukas Kaelin Making sense of the city : public spaces in the Philippines / Sacral Spaces Between Skyscrapers 69 Remmon E. Barbaza, editor. -- Quezon City : Ateneo de Manila University Press, [2019], c2019. Fernando N. Zialcita pages ; cm Cleaning the Capital 95 ISBN 978-971-550-911-4 The Campaign against Cabarets and Cockpits in the Prewar Greater Manila Area 1. -

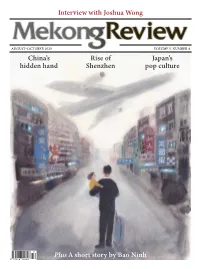

Interview with Joshua Wong Plus a Short Story by Bao Ninh China's

Interview with Joshua Wong AUGUST–OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 China’s Rise of Japan’s hidden hand Shenzhen pop culture 32 Plus A short story by Bao Ninh 9 772016 012803 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 AUGUST–OCTOBER 2020 HONG KONG 3 Kong Tsung-gan The edict INTERVIEW 5 Elaine Yu Joshua Wong HONG KONG 8 Jeffrey Wasserstrom City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong by Antony Dapiran; Aftershock: Essays from Hong Kong by Holmes Chan (ed) POEM 9 Lok Man Law ‘Records of a Floating Island’ CHINA 11 Tom Baxter Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City by Fang Fang POEMS Yuan Changming ‘Woman-radical: A feminist lesson in Chinese characters’; ‘Fragmenting: A sonnet in infinitives’ FOREIGN RELATIONS 12 Michael Reilly Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World by Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg SINGAPORE 13 Theophilus Kwek Air-Conditioned Nation Revisited: Essays on Singapore Politics by Cherian George NOTEBOOK 14 Anjan Sundaram Asia matters INDONESIA 15 Lara Norgaard The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World by Vincent Bevins MEMOIR 16 Helen Jarvis First, They Erased Our Name: A Rohingya Speaks by abiburahmanH BIOGRAPHY 17 Gozde Deniz Altunkeser MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman by Ben Hubbard URBAN AFFAIRS 18 Anne Stevenson-Yang The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City by Juan Du HISTORY 20 Paul French Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai by James Carter JOURNAL 21 Louis Raymond Personal history FICTION/TRAVEL 23 Emily -

Transnational Bataan Memories

TRANSNATIONAL BATAAN MEMORIES: TEXT, FILM, MONUMENT, AND COMMEMORATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2012 By Miguel B. Llora Dissertation Committee: Robert Perkinson, Chairperson Vernadette Gonzalez William Chapman Kathy Ferguson Yuma Totani Keywords: Bataan Death March, Public History, text, film, monuments, commemoration ii Copyright by Miguel B. Llora 2012 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank all my committee members for helping me navigate through the complex yet pleasurable process of undertaking research and writing a dissertation. My PhD experience provided me the context to gain a more profound insight into the world in which I live. In the process of writing this manuscript, I also developed a deeper understanding of myself. I also deeply appreciate the assistance of several colleagues, friends, and family who are too numerous to list. I appreciate their constant support and will forever be in their debt. Thanks and peace. iv ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the politics of historical commemoration relating to the Bataan Death March. I began by looking for abandonment but instead I found struggles for visibility. To explain this diverse set of moves, this dissertation deploys a theoretical framework and a range of research methods that enables analysis of disparate subjects such as war memoirs, films, memorials, and commemorative events. Therefore, each chapter in this dissertation looks at a different yet interrelated struggle for visibility. This dissertation is unique because it gives voice to competing publics, it looks at the stakes they have in creating monuments of historical remembrance, and it acknowledges their competing reasons for producing their version of history. -

Wika at Pasismo Politika Ng Wika at Araling Wika Sa Panahon Ng Diktadura

WIKA AT PASISMO POLITIKA NG WIKA AT ARALING WIKA SA PANAHON NG DIKTADURA Gonzalo A. Campoamor II i Wika at Pasismo: Politika ng Wika at Araling Wika sa Panahon ng Diktadura Zarina Joy Santos Maria Olivia O. Nueva España ©2018 Gonzalo A. Campoamor II at Tagapamahalang Editor Sentro ng Wikang Filipino-UP Diliman Sabine Banaag Gochuico Hindi maaaring kopyahin ang anumang Disenyo ng Pabalat bahagi ng aklat na ito sa alinmang paraan Ang disenyo ng pabalat ay reimahinasyon – grapiko, elektroniko, o mekanikal – ng pabalat ng Today’s Revolution: nang walang nakasulat na pahintulot Democracy (1971) ni Marcos na ginamit mula sa may hawak ng karapatang-sipi. sa kasalukuyang pag-aaral bilang batis at lunsaran ng politikal na pagsusuri The National Library of the Philippines ng wika sa panahon ng rehimeng batas CIP Data militar. Maria Laura V. Ginoy Recommended entry: Rizaldo Ramoncito S. Saliva Disenyo ng Aklat Campoamor, Gonzalo A., II. Wika at pasismo: politika ng wika at araling wika Kinikilala ng Sentro ng Wikang sa panahon ng diktadura / Gonzalo A. Filipino - UP Diliman ang Opisina ng Campoamor, II. -- Quezon City: Sentro Tsanselor ng Unibersidad ng Pilipinas para sa pagpopondo ng proyektong ito. ng Wikang Filipino, Unibersidad ng Pilipinas, [2018], c2018. pages ; cm Inilathala ng: Sentro ng Wikang Filipino-UP ISBN 978-971-635-060-9 Diliman 3/Palapag Gusaling SURP E. Jacinto St. UP Campus Diliman, 1. Filipino language – Political aspects. Lungsod Quezon I. Title. Telefax: 924-4747 Telepono: 981-8500 lok. 4583 499.211 PL6051 P820180105 ii PAG-AALAY Para kay Prop. Monico M. Atienza at sa mga biktima ng dahas ng wika at pasismo. -

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-Garde As a Democratic Gesture in Manila

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila Patrick D. Flores Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, Volume 1, Number 1, March 2017, pp. 13-38 (Article) Published by NUS Press Pte Ltd DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2017.0001 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/646476 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 20:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] “Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila PATRICK D. FLORES “This nation can be great again.” This was how Ferdinand Marcos enchanted the electorate in 1965 when he won his first presidential election at a time when the Philippines “prided itself on being the most ‘advanced’ in the region”.1 In his inaugural speech titled “Mandate to Greatness”, he spoke of a “national greatness” founded on the patriotism of forebears who had built the edifice of the “first modern republic in Asia and Africa”.2 Marcos conjured prospects of encompassing change: “This vision rejects and discards the inertia of centuries. It is a vision of the jungles opening up to the farmers’ tractor and plow, and the wilderness claimed for agriculture and the support of human life; the mountains yielding their boundless treasure, rows of factories turning the harvests of our fields into a thousand products.” 3 This line on greatness may prove salient in the discussion of the avant- garde in Philippine culture in the way it references “greatness” as a marker of the “progressive” as well as of the “massive”. -

The International and Transnational Construction of Authoritarian Rule in Island Southeast Asia, 1969-1977

THE INTERNATIONAL AND TRANSNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION OF AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN ISLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA, 1969-1977 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mattias Emerson Fibiger May 2018 © 2018 Mattias Emerson Fibiger THE INTERNATIONAL AND TRANSNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION OF AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN ISLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA, 1969-1977 Mattias Emerson Fibiger, Ph. D. Cornell University 2018 This dissertation examines the making of authoritarian rule in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore from 1969-1977. American President Richard Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger funneled vast sums of U.S. military and economic aid to island Southeast Asia via the anticommunist policy of the Nixon Doctrine. Facing no meaningful communist threats, national leaders in the region then used American largesse to construct and consolidate newly authoritarian regimes. Indonesia played a leading role in this process, disseminating its authoritarian state-building doctrine of national resilience and encouraging a “New Orderization” of island Southeast Asia. The transformation of the region’s political systems then reverberated on both sides of the Pacific. In the United States, diasporic communities and human rights groups lobbied against the provision of American aid to authoritarian regimes and contributed to a broad left-right coalition that undermined the Nixon and Ford administration’s core foreign policy projects. In island Southeast Asia, the narrowing of legitimate channels of political contestation produced an efflorescence of disloyal opposition movements, including communist, Islamist, and separatist insurgencies. The narrative emphasizes several themes, including the international and transnational construction of authoritarian rule, the importance of regional history, and the agency of American and Southeast Asian leaders and publics. -

Ang Bahay Ni Imelda

Ang Imeldific Representasyon at Kapangyarihan sa Sto. Niño Shrine sa Lungsod ng Tacloban MICHAEL CHARLESTON B. CHUA The paper is a reflection on the meaning of the Sto. Niño Shrine (Romualdez Museum) in Tacloban City, Leyte, the mansion Imelda Marcos ordered built in the early 1980s. Using Kapanahong Kasaysayan (the writing of Phiippine contemporaneous history as different from contemporary history and investigative journalism as defined by the West), the reflections will be corroborated with data from documents, biographies and statements of people close to the first lady, including the author’s interview with Madam Marcos herself, and will be contextualized to Philippine history and culture. According to Carmen Pedrosa, Imelda Marcos never lived in the mansion; it was “meant only to be viewed.” The house cum museum reflects the official representation of her past and her role as mother of the country. The design of the house and the many objects collected the world over, not only shows the great wealth and power that she gained, but also her claim of foreign and aristocratic origins. The objects also convey a representation of the first lady that she wanted to make her people and the world believe: That she was born and destined to lead. It will be observed that she wanted to show an image of herself just like the ancient Filipino Babaylan—narrator of the people’s story, healer of physical and social ills, spiritual leader of the people—the bearer of “ginhawa.” In the end, whatever representation a personality or an institution desires to ingrain in the national memory through text or concretely, it is the experience and socialization of the individual which will determine his or her image of that historical figure.