“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-Garde As a Democratic Gesture in Manila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

The Greening of the Project Management Cycle in the Construction Industry

The Greening of the Project Management Cycle in the Construction Industry Eliseo A. Aurellado 4 The Occasional Paper Series (OPS) is a regular publication of the Ateneo Graduate School of Business (AGSB) intended for the purpose of disseminating the views of its faculty that are considered to be of value to the discipline, practice and teaching of management and entrepreneurship. The OPS includes papers and analysis developed as part of a research project, think pieces and articles written for national and international conferences. The OPS provides a platform for faculty to contribute to the debate on current management issues that could lead to collaborative research, management innovation and improvements in business education. The views expressed in the OPS are solely those of the author (s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSB or the Ateneo de Manila University. Quotations or citations from articles published in the OPS require permission of the author. Published by the Ateneo de Manila University Graduate School of Business Ateneo Professional Schools Building Rockwell Drive, Rockwell Center, Makati City, Philippines 1200 Tel.: (632) 899-7691 to 96 or (632) 729-2001 to 2003 Fax: (632) 899-5548 Website: http://gsb.ateneo.edu/ Limited copies may be requested from the AGSB Research Unit Telefax: (632) 898-5007 Email: [email protected] Occasional Paper No.10 1 The Greening of the Project Management Cycle in the Construction Industry Eliseo A. Aurellado Ateneo de Manila University Graduate School of Business Introduction he turn of the 21st century saw a surge in the demand to be “green”. The general public’s environmental awareness, the demand from T consumers at all levels for more energy-efficient products, and the increasing prices of fossil fuels, have all conspired to put pressure on businesses to be more environment-friendly. -

'New Society' and the Philippine Labour Export Policy (1972-1986)

EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIppINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIPPINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) Mark Macaa Kyushu University Abstract: The ‘overseas Filipino workers’ (OFWs) are the largest source of US dollar income in the Philippines. These state-sponsored labour migrations have resulted in an exodus of workers and professionals that now amounts to approximately 10% of the entire country’s population. From a temporary and seasonal employment strategy during the early American colonial period, labour export has become a cornerstone of the country’s development policy. This was institutionalised under the Marcos regime (1965-1986), and especially in the early years of the martial law period (1972-81), and maintained by successive governments thereafter. Within this context, this paper investigates the relationship between Marcos’ ‘New Society’ agenda, the globalization of migrant labour, and state sponsorship of labour exports. In particular, it analyses the significance of attempts made to deploy education policy and educational institutions to facilitate the state’s labour export drive. Evidence analyzed in this paper suggests that sweeping reforms covering curricular policies, education governance and funding were implemented, ostensibly in support of national development. However, these measures ultimately did little to boost domestic economic development. Instead, they set the stage for the education system to continue training and certifying Filipino skilled labour for global export – a pattern that has continued to this day. Keywords: migration, labour export, education reforms, Ferdinand Marcos, New Society Introduction This paper extends a historical analysis begun with an investigation of early Filipino labour migration to the US and its role in addressing widespread poverty and unemployment (Maca, 2017). -

INTERLACED JOURNEYS INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art

INTERLACED JOURNEYS INTERLACED INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art Edited by Patrick D. Flores & Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art INTERLACED JOURNEYS| Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art brings together the work of some of the most engaging art historians and curators from Southeast Asia and beyond that explores the notion of diaspora in contemporary visual culture. Regional attention on this particular condition of movement and resettlement has oen been conned to sociological studies, while the place of diaspora in Southeast Asian contemporary art remains mostly unexplored. is is the rst anthology to examine the subject from the complex perspective of artistic and curatorial practice as it attempts to propose multiple narratives of diaspora in relation to a range of articulations in the contemporary context. INTERLACED JOURNEYS Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art Edited by Patrick D. Flores & Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Editing Patrick D. Flores Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani Copyediting Thelma Arambulo Carlos Quijon, Jr. First and foremost, we would like to express our sincere appreciation to the writers whose insightful Design chapters, developed for this publication, have helped to advance the discourse on migration and Belle Leung for Osage Design diaspora, Southeast Asia, and contemporary Southeast Asian art. We hope this publication to be but the initial step towards a larger research and exploration on the topic of migration and border crossing Publication Coordination in the region. Carlos Quijon, Jr. Our heartfelt gratitude goes to the artists included in this book whose invaluable art practices and Publication Support viewpoints have inspired the writers and editors. -

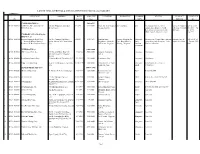

LIST of MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS with STATUS (As of July 2017)

LIST OF MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS WITH STATUS (As of July 2017) "ANNEX C" APPLICANT ADDRESS DATE AREA SIZE LOCATION BARANGAY COMMO- STATUS CONTACT CONTACT ID FILED (Has.) DITY PERSON NO. UNDER PROCESS (1) 5460.8537 1 APSA -000067 XIMICOR, INC. formerly K.C. 105 San Miguel St., San Juan 02/12/96 3619.1000 Diadi, Nueva Vizcaya & San Luis,Balete gold Filed appeal with the Mines Romeo C. Bagarino Fax no. (075) Devt. Phils. Inc. Metro Manila Cordon, Isabela Adjudication Board re: MAB - Director (Country 551-6167 Cp. Decision on adverse claim with Manager) no. 0919- VIMC, issued 2nd-notice dated 6243999 UNDER EVALUATION by the 4/11/16 MGB C.O. (1) 1. APSA -0000122 Kaipara Mining & Devt. Corp. No. 215 Country Club Drive, 10/22/04 1841.7537 Sanchez Mira, Namuac. Bangan, Sta. Magnetite Forwarded to Central Office but was Silvestre Jeric E. (02) 552-2751 ( formerly Mineral Frontier Ayala Alabang Vill. Muntinlupa Pamplona, Abulug & Cruz, Bagu,Masisit, Sand, returned due to deficiencies. Under Lapan - President Fax no. 555- Resources & Development Corp.) City Ballesteros, Cagayan Biduang, Magacan titanium, Final re-evaluation 0863 Vanadium WITHDRAWN (3) 23063.0000 1 APSA -000032 CRP Cement Phil. Inc. 213 Celestial Mary Bldg.950 11/23/94 5000.0000 Antagan, Tumauini, Limestone Withdrawn Arsenio Lacson St. Sampaloc, Isabela Manila 2 APSA -000038 Penablanca Cement Corp. 15 Forest Hills St., New Mla. Q.C. 1/9/1995 9963.0000 Penablanca, Cag. Limestone Withdrawn 3 APSA -000054 Yong Tai Corporation 64-A Scout Delgado St., Quezon 11/24/1995 8100.0000 Cabutunan Pt. & Twin Limestone, Withdrawn per letter dated City Peaks, sta. -

THE POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA the POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA Linda K

THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA Linda K. Richter 2018 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880163 (PDF) 9780824880170 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgments vi Abbreviations Used in Text viii 1. The Politics of Tourism: An Overview 1 2. About Face: The Political Evolution of Chinese Tourism Policy 25 3. The Philippines: The Politicization of Tourism 57 4. Thailand: Where Tourism and Politics Make Strange Bedfellows 92 5. Indian Tourism: Pluralist Policies in a Federal System 115 6. Creating Tourist “Meccas” in Praetorian States: Case Studies of Pakistan and Bangladesh 153 Pakistan 153 Bangladesh 171 7. Sri Lanka and the Maldives: Islands in Transition 178 Sri Lanka 178 The Maldives 186 8. Nepal and Bhutan: Two Approaches to Shangri-La 190 Nepal 190 Bhutan 199 9. -

Download This PDF File

Pagbahay sa Rehimen Ang Bagong Lipunan at ang Retorika ng Pamilya sa Arkitekturang Marcosian Juan Miguel Leandro L. Quizon Abstrak Ayon sa kasaysayan, sinasalamin ng magagarang gusali ang adhikain ng isang pamahalaang magmukhang progresibo ang bansa. Ang edifice complex ay isang sakit kung saan nahuhumaling ang isang rehimen na magpatayo ng mga nagsisilakihan at magagarbong gusali na sisimbulo sa pambansang kaunlaran. Noong dekada 1970, sa ilalim ng Rehimeng Marcos, ginamit nila ang kanilang kapangyarihan upang makapagpatayo ng mga gusaling ito para sa kanilang propaganda. Layunin ng papel na itong ungkatin kung paano ginamit ng Rehimeng Marcos ang retorika ng pamilya upang maisulong ang pagpapatupad ng kanilang adhikaing mapaniwala ang taumbayan na ang kanilang mga gawain ay para sa ikabubuti ng bansa. Gamit ang architectonic framework ni Preziosi at ang konsepto ng spatial triad ni Lefebvre, uungkatin ko ang usapin kung paano ginamit ng rehimen ang retorika ng pamilyang Pilipino upang paniwalain na tinatahak nila ang pambansang kaunlaran, ngunit ito ay para lamang sa kakaunting mayayaman at nasa kapangyarihan. Sa huli, naipatayo ang mga gusaling ito upang ilahad at patuloy na paigtingin ang pambansang imahinasyon na ang Pilipinas ay iisang pamilya sa ilalim ng diktaduryang Marcos. Mga Panandang Salita arkitektura, Batas Militar, kasaysayan, Marcos, pamahalaan Because President Marcos has a thoroughly organized mind, I am able to apply energies to the social, cultural, and welfare spheres of our common life – not as an official with power and responsibility but as a Filipino woman, a wife, sharing a common fate with my husband. – Imelda Marcos But the newspapers were full of groundbreaking ceremonies; Imeldawas flitting charmingly back and forth between ribbon-cutting, and no one else could possibly trace every peso anyway. -

Philippine Labor Group Endorses Boycott of Pacific Beach Hotel

FEATURE PHILIPPINE NEWS MAINLAND NEWS inside look Of Cory and 5 Bishop Dissuades 11 Filipina Boxer 14 AUG. 29, 2009 Tech-Savvy Spiritual Leaders from to Fight for Filipino Youth Running in 2010 World Title H AWAII’ S O NLY W EEKLY F ILIPINO - A MERICAN N EWSPAPER PHILIPPINE LABOR GROUP ENDORSES BOYCOTT OF PACIFIC BEACH HOTEL By Aiza Marie YAGO hirty officers and organizers from different unions conducted a leafleting at Sun Life Financial’s headquarters in Makati City, Philippines last August 20, in unity with the protest of Filipino T workers at the Pacific Beach Hotel in Waikiki. The Trade Union Congress of the ternational financial services company, is Philippines (TUCP) had passed a resolu- the biggest investor in Pacific Beach Hotel. tion to boycott Pacific Beach Hotel. The Sun Life holds an estimated US$38 million resolution calls upon hotel management to mortgage and is in the process of putting rehire the dismissed workers and settle up its market in the Philippines. the contract between the union and the “If Sun Life wants to do business in company. the Philippines, the very least we can ex- Pacific Beach Hotel has been pect in return is that it will guarantee fair charged by the U.S. government with 15 treatment for Filipino workers in the prop- counts of federal Labor Law violations, in- erties it controls,” says Democrito Men- cluding intimidation, coercion and firing doza, TUCP president. employees for union activism. In Decem- Rhandy Villanueva, spokesperson for ber 2007, the hotel’s administration re- employees at Pacific Beach Hotel, was fused to negotiate with the workers’ one of those whose position was termi- legally-elected union and terminated 32 nated. -

Download ART ARCHIVE 01

ART ARCHIVE 01 CONTENTS The Japan Foundation, Manila Introduction ART ARCHIVE 01 NEW TRAJECTORIES OF CONTEMPORARY VISUAL AND PERFORMING ARTS IN THE PHILIPPINES by Patricia Tumang Retracing Movement Redefining Contemporary Histories & Performativity Visual Art EXCAVATING SPACES AND HISTORIES: UNDERSTANDING THE CONTEMPORARY FILTERS: The Case of Shop 6 IN PHILIPPINE THEATER A View of Recent by Ringo Bunoan by Sir Anril Pineda Tiatco,PhD Philippine Contemporary Photography by Irwin Cruz VISUAL ARTS AND ACTIVISM IN THE PHILIPPINES: MAPPING OUT CONTEMPORARY DANCE Notes on a New Season of Discontent IN THE PHILIPPINES GLOBAL FILIPINO CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS by Lisa Ito-Tapang by Rina Angela Corpus by Jewel Chuaunsu BRIDGE OVER THE CURRENT: S A _ L A B A S / O U T S I D E R S: CONTEMPORARY VISUAL ART IN CEBU Artist-Run Festivals in the Philippines A Brief History of Why/When/Where We Do by Duffie Hufana Osental by Mayumi Hirano What We Do in Performance by Sipat Lawin Ensemble Contributor Biographies reFLECT & reGENERATE: A Community Conversation About Organizing Ourselves by Marika Constantino Directory of Philippine Art and Cultural Institutions ABOUT ART ARCHIVE 01 The Japan Foundation is the only institution dedicated to carrying out Japan’s comprehensive international cultural exchange programs throughout the world. With the objective of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue, the Japan Foundation creates global opportunities to foster friendship, trust, and mutual understanding. With a global network consisting of its Tokyo headquarters, the Kyoto office, two Japanese-language institutes, and 24 overseas offices in 23 countries, the Japan Foundation is active in three areas: Arts and Cultural Exchange, Japanese-Language Education, and Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange. -

David Medalla

DAVID MEDALLA Nació en Manila en 1942. David Medalla es considerado uno de los pioneros del land art, del kinetic art, del arte conceptual, del arte participativo y del live art. A la edad de 12 años asistió a la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York, como estudiante especial. Estudió teatro griego antiguo con Moses Hadas, teatro moderno con Eric Bentley, literatura moderna con Lionel Trilling, filosofía moderna con John Randall. También asistió al taller de poesía de Leonie Adams. En Nueva York, motivado por el poeta Jose García Villa y por el actor James Dean, David Medalla decide tomarse en serio la pintura. Medalla regresa a Manila a fines de los cincuenta, en donde se encuentra con los primeros patrocinadores de su obra, que incluyen al poeta catalán Jaime Gil de Biedma, al artista español Fernando Zóbel de Ayala y al pianista norteamericano Albert Faurot. En los años sesenta en París, el filósofo francés Gaston Bachelard introdujo la performance de Medalla, titulada "The Poet in Abyssinia: an imaginary biography of Arthur Rimbaud" en la Academia de Raymond Duncan, hermano de la legendaria bailarina Isadora Duncan, a quien le dedicó una performance con Shoe Taylor Guinness en el British Museum in 2001. En 1980, el poeta Louis Aragon (co-fundador del movimiento surrealista con André Breton y Philippe Soupault) introdujo otra de las performances de David Medalla, titulada "Anges du Jour, Anges du Nuit". Franklin Furnace y la Jerome Foundation patrocinaron la performance de Medalla "Five Immortals at Drop Dead Prices" en el Great Hall of Cooper Union en 1994 en Nueva York. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 467 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. their advice and thoughts; Andy Pownall; Gerry OUR READERS Deegan; all you sea urchins – you know who Many thanks to the travellers who used you are, and Jim Boy, Zaza and Eddie; Alexan- the last edition and wrote to us with der Lumang and Ronald Blantucas for the lift helpful hints, useful advice and interesting with accompanying sports talk; Maurice Noel anecdotes: ‘Wing’ Bollozos for his insight on Camiguin; Alan Bowers, Angela Chin, Anton Rijsdijk, Romy Besa for food talk; Mark Katz for health Barry Thompson, Bert Theunissen, Brian advice; and Carly Neidorf and Booners for their Bate, Bruno Michelini, Chris Urbanski, love and support. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. I. The sign or "target" for pages apparcntly lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagets)". II' it was possible to obtain the missing pagers) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrigh ted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, ctc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again vbcginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.