The Filipinos Protest Over Hero's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'New Society' and the Philippine Labour Export Policy (1972-1986)

EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIppINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) EDUCATION IN THE ‘NEW SOCIETY’ AND THE PHILIPPINE LABOUR EXPORT POLICY (1972-1986) Mark Macaa Kyushu University Abstract: The ‘overseas Filipino workers’ (OFWs) are the largest source of US dollar income in the Philippines. These state-sponsored labour migrations have resulted in an exodus of workers and professionals that now amounts to approximately 10% of the entire country’s population. From a temporary and seasonal employment strategy during the early American colonial period, labour export has become a cornerstone of the country’s development policy. This was institutionalised under the Marcos regime (1965-1986), and especially in the early years of the martial law period (1972-81), and maintained by successive governments thereafter. Within this context, this paper investigates the relationship between Marcos’ ‘New Society’ agenda, the globalization of migrant labour, and state sponsorship of labour exports. In particular, it analyses the significance of attempts made to deploy education policy and educational institutions to facilitate the state’s labour export drive. Evidence analyzed in this paper suggests that sweeping reforms covering curricular policies, education governance and funding were implemented, ostensibly in support of national development. However, these measures ultimately did little to boost domestic economic development. Instead, they set the stage for the education system to continue training and certifying Filipino skilled labour for global export – a pattern that has continued to this day. Keywords: migration, labour export, education reforms, Ferdinand Marcos, New Society Introduction This paper extends a historical analysis begun with an investigation of early Filipino labour migration to the US and its role in addressing widespread poverty and unemployment (Maca, 2017). -

Maritime Events Calendar

MARITIME REVIEW A Publication of The Maritime League Issue No. 17-4 July-August 2017 REARING A MARITIME NATION PhilMarine 2017 Learning from Korea Reactions on China War Threats PRS Stability Software CONTENTS CONTENTS 2 Maritime Review JUL-AUG 2017 CONTENTS CONTENTS Contents 5 The Maritime League Maritime Calendar ...................................................... 4 CHAIRMAN EMERITUS Feature Story Hon. Fidel V Ramos Rearing A Maritime Nation ........................................................ 5 HONORARY CHAIRMAN Hon. Arthur P Tugade Maritime Events PHILIPPINE MARITIME CONFERENCE at the 6 TRUSTEE AND PRESIDENT 4th PHILMARINE 2017 ............................................................. 6 Commo Carlos L Agustin AFP (Ret) Philippine Self-Reliant Defense Posture Program .................... 7 TRUSTEE AND VICE PRESIDENT VAdm Eduardo Ma R Santos (Ret) Chairman’s Page TRUSTEE AND TREASURER Learning from Korea ................................................................. 8 RAdm Margarito V Sanchez Jr AFP (Ret) 8 TRUSTEE AND AUDITOR Maritime Forum Commo Gilbert R Rueras (Ret) Proceedings: MF's 115 & 116 ..................................................11 TRUSTEES Edgar S Go Maritime Law Delfin J Wenceslao Jr An UNCLOS-based Durable Legal System for Regional Herminio S Esguerra Maritime Security and Ocean Governance for the Indo- Alberto H Suansing Pacific Maritime Region .......................................................... 13 VAdm. Emilio C Marayag (Ret) 16 Take Defense Treaty Action for Philippine Sovereignty -

Contents Briefsmarch 2018

CORPORATEContents BRIEFSMarch 2018 THE MONTH’S HIGHLIGHTS MINING 27 WORD FOR WORD 61 MGB team up with DOST for COMMENTARY nickel research SPECIAL REPORTS I.T. UPDATE 62 PH ranks 2nd least start-up POLITICAL friendly in Asia-Pacific 28 2017 Corruption Perceptions BUSINESS CLIMATE INDEX Index: PH drops anew CORPORATE BRIEFS 32 Sereno battles impeachment 38 in House, quo warranto in SC INFRASTRUCTURE 33 PH announces withdrawal from the ICC 75 New solar projects for Luzon 76 P94Bn infra projects in Davao Region THE ECONOMY 77 Decongesting NAIA-1 55 38 2017 budget deficit below limit on healthy government CONGRESSWATCH finances 40 More jobs created in January, 81 Senate approves First 1,000 but quality declines Days Bill Critical in Infant, 42 Exchange rate at 12-year low Child Mortality in February 82 Senate approves National ID 75 BUSINESS 84 Asia Pacific Executive Brief 102 Asia Brief contributors 55 Pledged investments in 2017, lowest in more than a decade 58 PH manufacturing growth to sustain double-digit recovery 59 PH tops 2018 Women in Business Survey 81 Online To read Philippine ANALYST online, go to wallacebusinessforum.com For information, send an email to [email protected] or [email protected] For publications, visit our website: wallacebusinessforum.com Philippine ANALYST March 2018 Philippine Consulting is our business...We tell it like it is PETER WALLACE Publisher BING ICAMINA Editor Research Staff: Rachel Rodica Christopher Miguel Saulo Allanne Mae Tiongco Robynne Ann Albaniel Production-Layout Larry Sagun Efs Salita Rose -

The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada

International Bulletin of Political Psychology Volume 5 Issue 3 Article 1 7-17-1998 From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada IBPP Editor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Editor, IBPP (1998) "From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada," International Bulletin of Political Psychology: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp/vol5/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Bulletin of Political Psychology by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editor: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada International Bulletin of Political Psychology Title: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada Author: Elizabeth J. Macapagal Volume: 5 Issue: 3 Date: 1998-07-17 Keywords: Elections, Estrada, Personality, Philippines Abstract. This article was written by Ma. Elizabeth J. Macapagal of Ateneo de Manila University, Republic of the Philippines. She brings at least three sources of expertise to her topic: formal training in the social sciences, a political intuition for the telling detail, and experiential/observational acumen and tradition as the granddaughter of former Philippine president, Diosdado Macapagal. (The article has undergone minor editing by IBPP). -

PVAO-Bulletin-VOL.11-ISSUE-2.Pdf

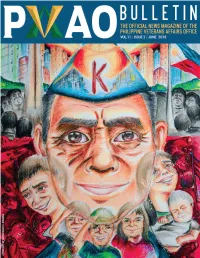

ABOUT THE COVER Over the years, the war becomes “ a reminder and testament that the Filipino spirit has always withstood the test of time.” The Official News Magazine of the - Sen. Panfilo “Ping” Lacson Philippine Veterans Affairs Office Special Guest and Speaker during the Review in Honor of the Veterans on 05 April 2018 Advisory Board IMAGINE A WORLD, wherein the Allied Forces in Europe and the Pacific LtGen. Ernesto G. Carolina, AFP (Ret) Administrator did not win the war. The very course of history itself, along with the essence of freedom and liberty would be devoid of the life that we so enjoy today. MGen. Raul Z. Caballes, AFP (Ret) Deputy Administrator Now, imagine at the blossoming age of your youth, you are called to arms to fight and defend your land from the threat of tyranny and oppression. Would you do it? Considering you have a whole life ahead of you, only to Contributors have it ended through the other end of a gun barrel. Are you willing to freely Atty. Rolando D. Villaflor give your life for the life of others? This was the reality of World War II. No Dr. Pilar D. Ibarra man deserves to go to war, but our forefathers did, and they did it without a MGen. Alfredo S. Cayton, Jr., AFP (Ret) moment’s notice, vouchsafing a peaceful and better world to live in for their children and their children’s children. BGen. Restituto L. Aguilar, AFP (Ret) Col. Agerico G. Amagna III, PAF (Ret) WWII Veteran Manuel R. Pamaran The cover for this Bulletin was inspired by Shena Rain Libranda’s painting, Liza T. -

THE POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA the POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA Linda K

THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA Linda K. Richter 2018 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880163 (PDF) 9780824880170 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgments vi Abbreviations Used in Text viii 1. The Politics of Tourism: An Overview 1 2. About Face: The Political Evolution of Chinese Tourism Policy 25 3. The Philippines: The Politicization of Tourism 57 4. Thailand: Where Tourism and Politics Make Strange Bedfellows 92 5. Indian Tourism: Pluralist Policies in a Federal System 115 6. Creating Tourist “Meccas” in Praetorian States: Case Studies of Pakistan and Bangladesh 153 Pakistan 153 Bangladesh 171 7. Sri Lanka and the Maldives: Islands in Transition 178 Sri Lanka 178 The Maldives 186 8. Nepal and Bhutan: Two Approaches to Shangri-La 190 Nepal 190 Bhutan 199 9. -

Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS PASIG-MARIKINA RIVER CHANNEL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PHASE III) SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT IN ACCORDANCE WITH JICA GUIDELINES FOR ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS SEPTEMBER 2011 PHASE IV (Improvement of Upper Marikina River & Construction of MCGS) PHASE II & III (Improvement of Pasig River) PHASE III (Improvement of Lower Marikina River) Project Location Map TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Location Map List of Tables List of Figures Abbreviations and Measurement Units CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………… 1 1.1 Purpose of Review and Supplemental Study…………..……………………… 1 1.2 Scope of Work…………………………………………………………………. 1 1.3 General Description of the Project…………………………………………….. 1 CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF ECC AND EIS(1998)………………………………..... 3 2.1 Validity of ECC………………………………………………………………… 3 2.2 Compatibility of EIS(1998) with PEISS Requirements……………………….. 3 2.3 Compatibility of EIS(1998) with JICA Guidelines……………………………. 3 2.3.1 Overall Comparisons between EIS(1998) and JICA Guidelines……... 4 2.3.2 Public Consultation and Scoping……………………………………... 5 2.3.3 Summary of Current Baseline Status of Natural and Social Environment………………………………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 3 CURRENT LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES…… 8 3.1 Overall Legal Framework……………………………………………………… 8 3.2 Procedures……………………………………………………………………… 8 3.3 Projects Covered by PEISS…………………………………………………….. 9 3.4 Responsible Government Institutions for PEISS………………………………. 11 3.5 Required Documents under PEISS…………………………………………….. 12 CHAPTER 4 SUPPLEMENTAL STUDY………………………………………… 17 4.1 Scope of Supplemental Study………………………………………………….. 17 4.2 Physical Environment…………………………………………………………. 17 4.2.1 Area of Concern………………………………………………………. 17 4.2.2 Air Quality Noise and Vibration……………………………………… 18 4.2.3 Water Resources……………………………………………………… 21 4.2.4 Water Quality…………………………………………………………. -

November–December 2018

NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2018 FROM THE CHAIRMAN’S DESK CAV JAIME S DE LOS SANTOS ‘69 Values that Define Organizational Stability The year is about to end. In a few months which will culminate Magnanimity – Being forgiving, being generous, being in the general alumni homecoming on February 16, 2019, a new charitable, the ability to rise above pettiness, being noble. What a leadership will take over the reins of PMAAAI. This year has been a nice thing to be. Let us temper our greed and ego. Cavaliers are very challenging year. It was a wake-up call. Slowly and cautiously blessed with intellect and the best of character. There is no need to we realized the need to make our organization more responsive, be boastful and self-conceited. relevant and credible. We look forward to new opportunities and Gratitude – The thankful appreciation for favors received and not be stymied by past events. According to Agathon as early as the bigness of heart to extend same to those who are in need. Let 400BC wrote that “Even God cannot change the past”. Paule-Enrile us perpetuate this value because it will act as a multiplier to our Borduas, another man of letters quipped that “the past must no causes and advocacies. longer be used as an anvil for beating out the present and the Loyalty - Loyalty suffered the most terrible beating among the future.” virtues. There was a time when being loyal, or being a loyalist, is George Bernard Shaw, a great playwright and political activist like being the scum of the earth, the flea of the dog that must be once said, “Progress is impossible without change, and those who mercilessly crashed and trashed. -

A Publication of the Philippine Military Academy Alumni Association, Inc. May - June 2016

A publication of the Philippine Military Academy Alumni Association, Inc. May - June 2016 CAVALIER MAGAZINE PMA Alumni Center, Camp Aguinaldo, Q.C. Re-entered as second class mail matter at the Camp Aguinaldo Post Office on April 3, 2008 Early ABOUT THE COVER on in the training of cadets, they are indoctrinated on the basics of customs and traditions of the service. Surprisingly, inspite of the difficulties which www.pmaaai.com characterize the life of a plebe, what they learned in the indoctrination process are deeply ingrained, clearly In ThIs Issue remembered and passionately treasured. Then, they PMAAAI Chapters receive Gabay Laya Class 2016 ..................................................6 leave the portals of the Academy and venture into the The month of April saw three chapters of PMAAAI as they enthusiastically receive outside world-idealistic, eager and courageous. They the new 2LTs and ensigns into their respective folds. notice that, outside, things are quite different in the Letter to the Editor ................................................................................................8 PMAAAI Director Cav Rosalino A Alquiza ’55 responds to the comments in the profession of arms i.e., manner of conducting military Class Call sections of the March-April issue of the Cavalier Magazine made by Class honors, leadership idiosyncracies that defy doctrines, ’56 (pertaining to the graduation ranking in a CGSC class) and by Class 1960 (on resolutions submitted for ratification during the January 2016 Alumni Convention formal superior-subordinate protocols different from and giving of PMAAAI Valor Award to recipients of AFP Medal of Valor. informal upperclass-underclass relationships. The long gray line: root of our commitment to the service This is now the situation faced both by new by Cav Olick R Salayo ‘01 .......................................................................................9 The author traces the strong commitments of Academy graduates to the traditions graduates and older alumni. -

Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UW Law Digital Commons (University of Washington) Washington International Law Journal Volume 15 Number 1 2-1-2006 It's All the Rage: Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy Dante B. Gatmaytan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Dante B. Gatmaytan, It's All the Rage: Popular Uprisings and Philippine Democracy, 15 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 1 (2006). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol15/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2006 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association IT’S ALL THE RAGE: POPULAR UPRISINGS AND PHILIPPINE DEMOCRACY † Dante B. Gatmaytan Abstract: Massive peaceful demonstrations ended the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines twenty years ago. The “people power” uprising was called a democratic revolution and inspired hopes that it would lead to the consolidation of democracy in the Philippines. When popular uprisings were later used to remove or threaten other leaders, people power was criticized as an assault on democratic institutions and was interpreted as a sign of the political immaturity of Filipinos. The literature on people power is presently marked by disagreement as to whether all popular uprisings should be considered part of the people power tradition. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. I. The sign or "target" for pages apparcntly lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagets)". II' it was possible to obtain the missing pagers) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrigh ted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, ctc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again vbcginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

1St Semester CY 2018 & Annual CY 2017

Highlights Of Accomplishment Report 1st Semester CY 2018 & Annual CY 2017 Prepared by: Corporate Planning and Management Staff Table of Contents TRAFFIC DISCIPLINE OFFICE ……………….. 1 TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT Income from Traffic Fines Traffic Direction & Control; Metro Manila Traffic Ticketing System Commonwealth Ave./ Macapagal Ave. Speed Limit Enforement Bus Management and Dispatch System South West Integrated Provincial Transport System (SWIPTS) Bicycle-Sharing Scheme Anti-Jaywalking Operations Anti-Illegal Parking Operations Enforcement of the Yellow Lane and Closed-Door Policy Anti-Colorum and Out-of-Line Operations Operation of the TVR Redemption Facility Personnel Inspection and Monitoring Road Emergency Operations (Emergency Response and Roadside Clearing) Towing and Impounding Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) No-Contact Apprehension Policy TRAFFIC ENGINEERING Design and Construction of Pedestrian Footbridges Traffic Survey Roadside Operation Metro Manila Accident Reporting and Analysis System (MMARAS) Application of Thermoplastic and Traffic Cold Paint Pavement Markings Upgrading of Traffic Signal System Traffic Signal Operation and Maintenance Fabrication and Manufacturing/ Maintenance of Traffic Road Signs/ Facilities TRAFFIC EDUCATION OTHER TRAFFIC IMPROVEMENT-RELATED SPECIAL PROJECTS/ MEASURES Alignment of 3 TDO Units Regulating Provincial Buses along EDSA Establish Truck Lanes along C-2 Amendment to Coverage of the “No Physical Contact Apprehension Policy” Amendments to “Light Truck”