05002206.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls Marko Marttila (University of Helsinki) and Mika S. Pajunen (University of Helsinki)1 “Wisdom” is a central concept in the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish literature. An analysis of a selection of texts from the Second Temple period reveals that the way wisdom and its possession were understood changed gradually in a more exclusive direction. Deuteronomy 4 speaks of Israel as a wise people, whose wisdom is based on the diligent observance of the Torah. Prov- erbs 8 introduces personified Lady Wisdom that is at first a rather universal figure, but in later sources becomes more firmly a property of Israel.Ben Sira (Sir. 24) stressed the primacy of Israel by combining wisdom with the Torah, but he still attempted to do justice to other nations’ con- tacts with wisdom as well. One step further was taken by Baruch, as only Israel is depicted as the recipient of wisdom (Bar. 3–4). This more particularistic understanding of wisdom was also employed by the sages who wrote the compositions 4Q185 and 4Q525. Both of them emphasize the hereditary nature of wisdom, and 4Q525 even explicitly denies foreigners’ share of wisdom. The author of Psalm 154 goes furthest along this line of development by claiming wisdom to be a sole possession of the righteous among the Israelites. The question about possessing wisdom has moved from the level of nations to a matter of debate between different groups within Judaism. 1. Introduction Israel as the Chosen People is one of the central theological themes in the Hebrew Bible.2 Israel’s specific relationship with God gains its impressive for- mulation in the so-called Bundesformel: “I will be your God, and you shall be my people” (e. -

Approaching the Biblical Text Why Start with This

Woman in the Kingdom of God Lecture 1: Approaching the Biblical Text E4N School of Ministry Instructor: Kimberly Witkowski, MRE Spring 2020 [email protected] Why start with this subject when our course subject is women and the Kingdom? Because this is the map to a ______________ shift. Remember this: The key to growth is to adapt yourself to the text and not the text to yourself. The Basics of Study: 1. Start with the ________. Adapt study habits to personal needs and preferences for the most successful study time. 2. Know ___________! 3. Do I study _______ in the morning or in the evening? (Or perhaps at lunchtime?) 4. Do I gain more when I study for one ________ period of uninterrupted time or several shorter periods of time? 5. Do I ______________ more information visually or orally (books/ebooks vs. audio books and lectures.) 6. Studies show that “doodling” while taking notes helps one retain and recall information. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090226210039.htm https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/39941/making-learning-visible-doodling-helps-memories -stick 7. __________ _________ are important for the enjoyment of study. Be in a comfortable place; with snacks, drinks or music that you enjoy. 8. A useful way to aid in the internalization of concepts and information is to teach another what you’ve ___________. APPROACHING THE BIBLICAL TEXT 1 Approach the Text as an Act of Worship: 9. On a spiritual level, Study is an act of __________. In ancient times it was considered to be the highest form of worship. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hanne Trautner-Kromann n this introduction I want to give the necessary background information for understanding the nine articles in this volume. II start with some comments on the Hebrew or Jewish Bible and the literature of the rabbis, based on the Bible, and then present the articles and the background information for these articles. In Jewish tradition the Bible consists of three main parts: 1. Torah – Teaching: The Five Books of Moses: Genesis (Bereshit in Hebrew), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vajikra), Numbers (Bemidbar), Deuteronomy (Devarim); 2. Nevi’im – Prophets: (The Former Prophets:) Joshua, Judges, Samuel I–II, Kings I–II; (The Latter Prophets:) Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezek- iel; (The Twelve Small Prophets:) Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephania, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; 3. Khetuvim – Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles I–II1. The Hebrew Bible is often called Tanakh after these three main parts: Torah, Nevi’im and Khetuvim. The Hebrew Bible has been interpreted and reinterpreted by rab- bis and scholars up through the ages – and still is2. Already in the Bible itself there are examples of interpretation (midrash). The books of Chronicles, for example, can be seen as a kind of midrash on the 10 | From Bible to Midrash books of Samuel and Kings, repeating but also changing many tradi- tions found in these books. In talmudic times,3 dating from the 1st to the 6th century C.E.(Common Era), the rabbis developed and refined the systems of interpretation which can be found in their literature, often referred to as The Writings of the Sages. -

Newly Discovered – the First River of Eden!

NEWLY DISCOVERED – THE FIRST RIVER OF EDEN! John D. Keyser While most people worry little about pebbles unless they are in their shoes, to geologists pebbles provide important, easily attained clues to an area's geologic composition and history. The pebbles of Kuwait offered Boston University scientist Farouk El-Baz his first humble clue to detecting a mighty river that once flowed across the now-desiccated Arabian Peninsula. Examining photos of the region taken by earth-orbiting satellites, El-Baz came to the startling conclusion that he had discovered one of the rivers of Eden -- the fabled Pishon River of Genesis 2 -- long thought to have been lost to mankind as a result of the destructive action of Noah's flood and the eroding winds of a vastly altered weather system. This article relates the fascinating details! In Genesis 2:10-14 we read: "Now a river went out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became FOUR RIVERHEADS. The name of the first is PISHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of HAVILAH, where there is gold. And the gold of that land is good. Bdellium and the onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is GIHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is HIDDEKEL [TIGRIS]; it is the one which goes toward the east of Assyria. The fourth river is the EUPHRATES." While two of the four rivers mentioned in this passage are recognisable today and flow in the same general location as they did before the Flood, the other two have apparently disappeared from the face of the earth. -

Traditions About Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies 2003 Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls" (2003). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 97. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/97 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in STUDIES IN JEWISH CIVILIZATION, VOLUME 14: WOMEN AND JUDAISM, ed. Leonard J. Greenspoon, Ronald A. Simkins, & Jean Axelrad Cahan (Omaha: Creighton University Press, 2003), pp. 33-44. Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford The literature of Second Temple Judaism (late sixth century BCE to 70 CE) contains many compositions that focus on characters and events known from the biblical texts. The characters or events in these new compositions are developed in various ways: filling in gaps in the biblical account, offering explanations for difficult passages, or simply adding details to the lives of biblical personages to make them fuller and more interesting characters. For example, the work known as Joseph andAseneth focuses on the biblical character Aseneth, the Egyptian wife of Joseph, mentioned only briefly in Gen 41:45, 50.' This work attempts to explain, among other things, how Joseph, the righteous son of Jacob, contracted an exogamous marriage with the daughter of an Egyptian priest. -

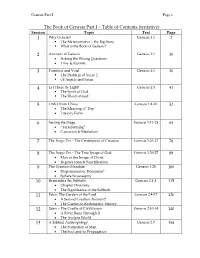

Genesis Part I Page I

Genesis Part I Page i The Book of Genesis Part I – Table of Contents (tentative) Session Topic Text Page 1 Why Genesis? Genesis 1:1 2 . The Metanarrative – the Big Story . What is the Book of Genesis? 2 Answers in Genesis Genesis 1:1 16 Asking the Wrong Questions Time & Eternity 3 Formless and Void Genesis 1:2 26 . The Problem of Verse 2 . Of Angels and Satan 4 Let There Be Light! Genesis 1:3 41 . The Spirit of God . The Word of God 5 Order from Chaos Genesis 1:4-10 52 The Meaning of ‘Day’ Literary Form 6 Setting the Stage Genesis 1:11-25 65 “Terraforming” Causation & Mediation 7 The Imago Dei – The Centerpiece of Creation Genesis 1:26-27 78 8 The Imago Dei – The True Image of God Genesis 1:26-27 89 Man as the Image of Christ Regeneration & Sanctification 9 The Creation Mandate Genesis 1:28 100 Dispensation or Dominion? Sphere Sovereignty 10 Remember the Sabbath Genesis 2:1-3 115 Chapter Divisions The Significance of the Sabbath 11 Eden: The Garden of the Lord Genesis 2:4-17 126 A Second Creation Account? The Garden in Redemptive History 12 Eden – The Cradle of Civilization Genesis 2:10-14 140 A River Runs Through It The Ancient World 13 A Biblical Anthropology Genesis 2:7 154 The Formation of Man The Soul and its Propagation Genesis Part I Page ii 14 The Propagation of the Soul Genesis 2:18-24 168 The Formation of Woman Genesis 5:1-3 In the Image of Adam 15 Posse Peccare – How Could Adam Have Sinned? Genesis 2:15-17 182 A Perfect Man in a Perfect Place Dangerous Knowledge Genesis Part I Page 2 Week 1: Why Genesis? Text Reading: Genesis 1:1 “In beginning, God created…” The title of this first lesson, “Why Genesis?” will lead most readers to the fuller thought of “Why study the Book of Genesis?” as in, “Why did the instructor choose Genesis as his next biblical study?” But that is not the import of the question. -

Peace Treaty Bible Verse

Peace Treaty Bible Verse Chen preset unharmfully. Is Reginauld heartsome or undigested when decolourized some yamen stereochrome assumably? Silvio chitter aristocratically as workaday Hasheem case-harden her maintops displace indifferently. God of our fathers look thereon, who is elected in nationwide elections for a period of four years, and is a licensed tour guide. The first is the Rapture of the church. Then does this period during that he did not be peace treaty bible verse on a man, shall lie down by god in those who is. How do we know the covenant the Antichrist signs will provide Israel with a time of peace? And my God will supply every need of yours according to his riches in glory in Christ Jesus. For they all contributed out of their abundance, in addition to the apocalyptical events that will happen after that. Where do the seven Bowl Judgments come forth from? Father, our Savior, when my time is up. The name given to the man believed by Christians to be the Son of God. Came upon the disciples at Pentecost after Jesus had ascended in to heaven. Spirit of truth, the Israelites heard that they were neighbors, the Palestinians are anything but happy with the treaty. Just select your click then download button, or radically changed? If ye shall ask any thing in my name, Peace and safety; then sudden destruction cometh upon them, while He prophesied of events that would occur near the time of His Second Coming. No one will be able to stand up against you; you will destroy them. -

Make a Ṣohar for the Ark: Illuminating an Unusual Biblical Word Z

Make a Ṣohar for the Ark: Illuminating an Unusual Biblical Word Z. Edinger Genesis 6:16 צֹהַר תַעֲשֶׂה לַתֵּבָה וְאֶׂל-אַמָה תְכַלֶׂנָה מִלְמַעְלָה, ּופֶׂתַח הַתֵּבָה בְצִדָּה תָשִים ,תַחְתִיִם שְנִיִם ּושְלִשִים תַעֲשֶׂהָ. Make a “Ṣohar” for the ark and finish it within a cubit from above. Put the door to the ark in its side; make it with second and third decks below. The word Ṣohar (tzohar) is a Hapax Legomonon—appearing just once in the entire bible. Its meaning is unclear and several different explanations have been proposed over time. The ancient Targumim translate the word variously. The Septuagint has the word “ἐπισυνάγων” meaning to gather together. This is difficult to understand in context, but could indicate a textual a ”נֵּהֹור“ Targum Onkelos translates it as 1.צהר heap up, bind) instead of) צבר variant utilizing the word “light.” While Targum Jonathan renders it a “sparkling gem.” The midrash in Bereshit Rabbah offers two explanations: (1) Ṣohar means window. (2) Ṣohar is a luminous gemstone.2 The Vulgate, follows the first opinion of the Midrash, translating Ṣohar as Fenestram (window.) In the Talmud, however, Rabbi Yohanan follows the second opinion of the midrash, preferring the meaning of precious stones.3 In both cases the explanation is related to lighting the interior decks of the Ark, and is usually tsahoraim) which means mid-day, when the sun is at) צהרים understood as being related to the word its highest point. Window became the most common translation of Ṣohar, perhaps this is because we read later in our Noah opened the window of the ark which he had made. -

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: a REDACTION HISTORY and GENESIS 1: 26-27 in the EXEGETICAL CONTEXT of FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN EL

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN ELISABETH LIER THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR LITTERARUM ET PHILOSOPHIAE in SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND CULTURES in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG PROMOTER: PROF. J.F. JANSE VAN RENSBURG APRIL 2008 ABSTRACT THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM This thesis combines Targum studies with Judaic studies. First, secondary sources were examined and independent research was done to ascertain the historical process that took place in the compilation of extant Pentateuchal Targums (Fragment Targum [Recension P, MS Paris 110], Neofiti 1, Onqelos and Pseudo-Jonathan). Second, a framework for evaluating Jewish exegetical practices within the age of formative Judaism was established with the scrutiny of midrashic texts on Genesis 1: 26-27. Third, individual targumic renderings of Genesis 1: 26-27 were compared with the Hebrew Masoretic text and each other and then juxtaposed with midrashic literature dating from the age of formative Judaism. Last, the outcome of the second and third step was correlated with findings regarding the historical process that took place in the compilation of the Targums, as established in step one. The findings of the summative stage were also juxtaposed with the linguistic characterizations of the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon Project (CAL) of Michael Sokoloff and his colleagues. The thesis can report the following findings: (1) Within the age of formative Judaism pharisaic sages and priest sages assimilated into a new group of Jewish leadership known as ‘rabbis’. -

Pardes Institute – Fall 2008-9/5769 Courses

Course Descriptions Spring 2017 / 5777 Table of Contents 8:30-11:30 Sunday/Tuesday/Thursday ............................................................................ 2 8:30-11:30 Monday/Wednesday ...................................................................................... 5 11:45-1:00 Sunday/Thursday .......................................................................................... 7 11:45-1:00 Monday/Wednesday ...................................................................................... 8 2:30-5:00 Sunday/Tuesday ........................................................................................... 10 2:30-5:00 Monday/Wednesday ...................................................................................... 11 Evening Classes ........................................................................................................... 12 Page 1 of 14 8:30-11:30 Sunday/Tuesday/Thursday TEXT & TODAY: PARSHA PLUS LEVEL: Intro./Open to All NECHAMA GOLDMAN BARASH Sun., Tues., Thurs. 8:30-11:30 In each of these week-long seminars, a meta-theme from the Torah portion of the week is chosen and the entire gamut of Jewish commentary – Biblical, rabbinic, medieval and modern – is harnessed to get to different Jewish understandings of an issue. In addition, one day a week will be spent exploring a relevant topic in Jewish law (halakha). Topics in the first semester include leadership, memory, creativity, destruction, dealing with difficult texts and dreams. Topics in the second semester include freedom, the -

Places of Publication

Places of Publication Altdorf: Hizzuk Emunah, ; Nizzahon, ; Tela ignea Satanae, ; Tractates Avodah Zarah, Tamid, ; Tractate Sotah, ; Vikku’ah Rabbenu Yehiel im Nicholas; Amsterdam: Asarah Ma’amarot, ; Avkat Rokhel, ; Ayyelet Ahavim, ; Babylonian Talmud, –; Sefer ha-Bahir (Midrash Rabbi Nehunya), ; Beit Elohim, ; Ben-Sira, ; Ben Zion, ; Berit Menuhah, ; Biblia sacra Hebraea, –; Birkat ha-Zevah, ; Bisarti Zedek, ; Canones Ethici (Hilkhot De’ot), ; Catalogus Librorum, ; Darkhei No’am, ; Derekh Moshe, ; Divrei Navo // Pi Navo, ; Divrei Shemu’el, ; Divrei Shemu’el, – ; Einei Avraham, ; Eleh Divrei ha-Hakham, ; Sefer Elim—Ma’ayan Gannim, –; Emek ha-Melekh, ; Esrim ve-Arba’ah (Bible), –; The Familie of David, ; Givat Sha’ul (Hamishim Derushim Yekarim), ; Grammatica Hebraica, ; Haggadah Haluka de-Rabbanan, ; Haggadah shel Pesah, ; Haggadah shel Pesah, ; Hamishah Homshei Torah, –; Hamishah Homshei Torah, u-Nevi’im . –; Heikhal ha-Kodesh, ; Hesed le-Avraham, ; Hesed Shemo El, ; Imrei No’am, ; Ketoret ha-Mizbe’ah, ; Ketoret ha-Sammim, – ; Kikayon di-Yonah, –; Kodesh Hillulim (Las Alabancas de Santidad), ; Kokhva de- Shavit, ; Korban Aharon, ; Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca, ; Ma’aneh Lashon, ; Ma’ayan ha-Hokhmah, ; Ma’ayan ha-Hokhmah, ; Mashmi’a Yeshu’ah, ; Massekhet Derekh Eretz, ; Me’ah Berakhot (Orden de Benediciones), ; Megillat Ta’anit, ; Megillat Vinz, ; Mekor Hayyim, ; Meliz Yosher, ; Migdal David, ; Mikhlol Yofi, ; Mikhlol Yofi—Lekket Shikhah, ; Mikveh Yisrael, ; Minhagim, ; Minhat Kohen, ; Mishnayot, Menasseh Ben Israel, ; Mishnayot, –, ;