Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian's Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Sethian Gnosticism by Joan Ann Lansberry

Sethian Gnosticism By Joan Ann Lansberry The label Gnosticism covers a varied group of religious and philosophical movements that existed in the first and second centuries CE. Today, those who consider themselves Gnostics seek transformative awakening from a material-based stupefaction. But back in the early centuries of the Christian Era, gnosticism was quite a hodge-podge of ideas deriving from the Corpus Hermeticum, the Jewish Apocalyptic writings, the Hebrew Scriptures themselves, and particularly Platonic philosophy. There's even some Egyptian texts, the Gospel of the Egyptians and three Steles of Seth. Seth? Is this Egyptian Set or Jewish Seth? Scholars are divided on this subject, but most of them say there is little connection. “Inasmuch as the Gnostic traditions pertaining to Seth derive from Jewish sources, we are led to posit that the very phenomenon of 'Sethian' Gnosticism per se is of Jewish, perhaps pre-Christian, origin.”1 So who is this Seth who features in Sethian Gnosticism? Birger Pearson says: “After examining the magical texts on Seth-Typhon and the Gnostic texts on Seth, I concluded that no relationship existed between Egyptian Seth and Gnostic Seth.”2 He further declares “By the time of the Gnostic literature no Egyptians except magicians worshipped Seth.”3 But were there any magicians who were also gnostics? Pearson continues: “Contrary to his earlier good standing, the Egyptian Seth becomes a demonic figure in the late Hellenistic period. It is inconceivable that Egyptian Seth was tied in with a hero of the Gnostic -

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls Marko Marttila (University of Helsinki) and Mika S. Pajunen (University of Helsinki)1 “Wisdom” is a central concept in the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish literature. An analysis of a selection of texts from the Second Temple period reveals that the way wisdom and its possession were understood changed gradually in a more exclusive direction. Deuteronomy 4 speaks of Israel as a wise people, whose wisdom is based on the diligent observance of the Torah. Prov- erbs 8 introduces personified Lady Wisdom that is at first a rather universal figure, but in later sources becomes more firmly a property of Israel.Ben Sira (Sir. 24) stressed the primacy of Israel by combining wisdom with the Torah, but he still attempted to do justice to other nations’ con- tacts with wisdom as well. One step further was taken by Baruch, as only Israel is depicted as the recipient of wisdom (Bar. 3–4). This more particularistic understanding of wisdom was also employed by the sages who wrote the compositions 4Q185 and 4Q525. Both of them emphasize the hereditary nature of wisdom, and 4Q525 even explicitly denies foreigners’ share of wisdom. The author of Psalm 154 goes furthest along this line of development by claiming wisdom to be a sole possession of the righteous among the Israelites. The question about possessing wisdom has moved from the level of nations to a matter of debate between different groups within Judaism. 1. Introduction Israel as the Chosen People is one of the central theological themes in the Hebrew Bible.2 Israel’s specific relationship with God gains its impressive for- mulation in the so-called Bundesformel: “I will be your God, and you shall be my people” (e. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Newly Discovered – the First River of Eden!

NEWLY DISCOVERED – THE FIRST RIVER OF EDEN! John D. Keyser While most people worry little about pebbles unless they are in their shoes, to geologists pebbles provide important, easily attained clues to an area's geologic composition and history. The pebbles of Kuwait offered Boston University scientist Farouk El-Baz his first humble clue to detecting a mighty river that once flowed across the now-desiccated Arabian Peninsula. Examining photos of the region taken by earth-orbiting satellites, El-Baz came to the startling conclusion that he had discovered one of the rivers of Eden -- the fabled Pishon River of Genesis 2 -- long thought to have been lost to mankind as a result of the destructive action of Noah's flood and the eroding winds of a vastly altered weather system. This article relates the fascinating details! In Genesis 2:10-14 we read: "Now a river went out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became FOUR RIVERHEADS. The name of the first is PISHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of HAVILAH, where there is gold. And the gold of that land is good. Bdellium and the onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is GIHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is HIDDEKEL [TIGRIS]; it is the one which goes toward the east of Assyria. The fourth river is the EUPHRATES." While two of the four rivers mentioned in this passage are recognisable today and flow in the same general location as they did before the Flood, the other two have apparently disappeared from the face of the earth. -

The-Gospel-Of-Mary.Pdf

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN GOSPEL TEXTS General Editors Christopher Tuckett Andrew Gregory This page intentionally left blank The Gospel of Mary CHRISTOPHER TUCKETT 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Christopher Tuckett, 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services Ltd., Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk ISBN 978–0–19–921213–2 13579108642 Series Preface Recent years have seen a signiWcant increase of interest in non- canonical gospel texts as part of the study of early Christianity. -

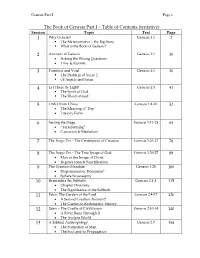

Genesis Part I Page I

Genesis Part I Page i The Book of Genesis Part I – Table of Contents (tentative) Session Topic Text Page 1 Why Genesis? Genesis 1:1 2 . The Metanarrative – the Big Story . What is the Book of Genesis? 2 Answers in Genesis Genesis 1:1 16 Asking the Wrong Questions Time & Eternity 3 Formless and Void Genesis 1:2 26 . The Problem of Verse 2 . Of Angels and Satan 4 Let There Be Light! Genesis 1:3 41 . The Spirit of God . The Word of God 5 Order from Chaos Genesis 1:4-10 52 The Meaning of ‘Day’ Literary Form 6 Setting the Stage Genesis 1:11-25 65 “Terraforming” Causation & Mediation 7 The Imago Dei – The Centerpiece of Creation Genesis 1:26-27 78 8 The Imago Dei – The True Image of God Genesis 1:26-27 89 Man as the Image of Christ Regeneration & Sanctification 9 The Creation Mandate Genesis 1:28 100 Dispensation or Dominion? Sphere Sovereignty 10 Remember the Sabbath Genesis 2:1-3 115 Chapter Divisions The Significance of the Sabbath 11 Eden: The Garden of the Lord Genesis 2:4-17 126 A Second Creation Account? The Garden in Redemptive History 12 Eden – The Cradle of Civilization Genesis 2:10-14 140 A River Runs Through It The Ancient World 13 A Biblical Anthropology Genesis 2:7 154 The Formation of Man The Soul and its Propagation Genesis Part I Page ii 14 The Propagation of the Soul Genesis 2:18-24 168 The Formation of Woman Genesis 5:1-3 In the Image of Adam 15 Posse Peccare – How Could Adam Have Sinned? Genesis 2:15-17 182 A Perfect Man in a Perfect Place Dangerous Knowledge Genesis Part I Page 2 Week 1: Why Genesis? Text Reading: Genesis 1:1 “In beginning, God created…” The title of this first lesson, “Why Genesis?” will lead most readers to the fuller thought of “Why study the Book of Genesis?” as in, “Why did the instructor choose Genesis as his next biblical study?” But that is not the import of the question. -

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About the Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack Title: The Origin of the New Testament URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin_nt.html Author(s): Harnack, Adolf (1851-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2005-04-20 General Comments: (tr. The Rev. J. R. Wilkinson) CCEL Subjects: All; Bible The Origin of the New Testament Adolf Harnack Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Prefatory Material. p. 2 I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the New Testament. p. 12 § 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to the Old Testament?. p. 13 § 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books beside the Gospels, and appears as a compilation with two divisions (ªEvangeliumº and ªApostolusº)?. p. 28 § 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not One only?. p. 38 § 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the New Testament? Why not severalÐor none at all?. p. 44 § 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did the Churches arrive at one common New Testament?. p. 49 II. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament. p. 57 § 1. The New Testament immediately emancipated itself from the conditions of its origin, and claimed to be regarded as simply a gift of the Holy Spirit. It held an independent position side by side with the Rule of Faith; it at once began to influence the development of doctrine, and it became in principle the final court of appeal for the Christian life. -

Poverty and Charity in Roman Palestine

Poverty and charity in Roman Palestine Gildas Hamel Abstract The present book reformats the text, notes, and appendices of the origi- nal 1990 publication by the University of California Press. Its pagination is different. There is no index. i D’ur vamm ha d’ur breur aet d’an Anaon re abred A.M.G. 31 Meurzh 1975 Y.M.H. 12 Geñver 1986 Contents Contents ii List of Figures iv List of Tables iv Introduction ix 1 Daily bread 1 1.1 Food items ............................. 2 1.2 Diets ................................ 19 1.3 Diseases and death ........................ 55 1.4 Conclusion ............................ 58 2 Poverty in clothing 61 2.1 Common articles of clothing ................... 61 2.2 Lack of clothing .......................... 70 2.3 Clothing and social status .................... 81 2.4 Conclusion ............................ 104 3 Causes of poverty 107 3.1 Discourse of the ancients on yields . 108 3.2 Aspects of agriculture: climate and soil . 116 3.3 Work and technical standards . 125 3.4 Yields ............................... 145 3.5 Population of Palestine . 159 3.6 Conclusion ............................ 163 4 Taxes and rents 165 4.1 Roman taxes . 168 ii Contents iii 4.2 Jewish taxes and history of tax burden . 171 4.3 Labor and ground rents . 176 4.4 Conclusion ............................ 190 5 The vocabulary of poverty 193 5.1 Explicit vocabulary: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek . 196 5.2 Explicit vocabulary: self-designations . 209 5.3 Greek and Jewish views on poverty and wealth . 229 5.4 Implicit vocabulary . 239 5.5 Conclusion ............................ 248 6 Charity in Roman Palestine 251 6.1 Discourses on charity . -

Arianism and Political Power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic Kingdoms

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2012 Reign of heretics: Arianism and political power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic kingdoms Christopher J. (Christopher James) Nofziger Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nofziger, Christopher J. (Christopher James), "Reign of heretics: Arianism and political power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic kingdoms" (2012). WWU Graduate School Collection. 244. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/244 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reign of Heretics: Arianism and Political Power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic Kingdoms By Christopher James Nofziger Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School Advisory Committee Chair, Dr. Peter Diehl Dr. Amanda Eurich Dr. Sean Murphy MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Elements of Gnostic Concepts in Depictions on Magical Gems

The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture No. 13 (1/2015) / ARTICLE GRAŻYNA BĄKOWSKA-CZERNER* (Jagiellonian University) Elements of Gnostic Concepts in Depictions on Magical Gems ABSTRACT Magical gems, also called Gnostic gems, are dated mainly to the 1st-3rd century. The depic- tions, symbols and inscriptions on them often refer to Gnosticism, a religious-philosophical current very popular in that period. The relics discussed were amulets. The syncretic icon- ographic solutions as well as the words and inscriptions on them were of great importance. Voces magicae, the names of gods, and also words unintelligible in any language frequent- ly appear. In order to maintain secrecy they were often written in code and clandestine names were used. To reach god, it was necessary to overstep the rules of ordinary lan- guage. Similarly to the Egyptian or Gnostic tradition, in Greco-Roman magic it was be- lieved that words and names had power. On gems, just as in magical papyri or on magical tablets the so-called charakteres were also used, i.e. symbols inspired by shapes of the Greek, or less frequently the Semitic, alphabet used by magi, astrologists and Gnostics. The kinds of depictions and ideas conveyed on magical gems are connected with Gnosticism. It might be stated that followers of this trend could also be among the produc- ers of the amulets, but too little is still known about it, because evidence of Gnosticism was destroyed after it was regarded as heresy. KEYWORDS magical gems, Gnostic, Roman period, iconography ____________________________ * Centre for Comparative Studies of Civilisations Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland e-mail: [email protected] 24 Grażyna Bąkowska-Czerner ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Magical gems, also called Gnostic gems, are amulets produced in the first centuries of our era.