An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the Social Presence Model to Explore Online and Blended Learning Experiences

Introducing the Social Presence Model to Explore Online and Blended Learning Experiences Aimee L. Whiteside University of Tampa Abstract This study explores the level of social presence or connectedness, in two iterations of a 13- month, graduate-level certificate program designed to help K-12 school leaders integrate technology in their districts. Vygotsky’s Social Development Theory serves as the theoretical lens for this programmatic research. The methods include a case study approach for coding discussions for 16 online courses using the pre-established Social Presence coding scheme as well as conducting instructor and student interviews and collecting observation notes on over a dozen face-to-face courses. The results of this study suggest the need for further research and development on the Social Presence coding scheme. Additionally, this study unveiled the Social Presence Model, a working model that suggests social presence consists of the following five integrated elements: Affective Association, Community Cohesion, Instructor Involvement, Interaction Intensity, and Knowledge and Experience. Finally, this study also highlighted the importance of multiple data sources for researchers, the need for researchers to request access to participant data outside the formal learning environment, and the inherently unique challenges instructors face with multimodal literacy and social presence in blended learning programs. Introduction As social learning theorist Etienne Wenger (1998) proclaims, “We are social beings…this fact is a central aspect of learning” (p. 4-5). We crave connections among one another within our learning environments. As instructors, we feel that spark of connected energy when students discover they have the same hometown or when they share a love of a particular animal, similar hobbies or career interests. -

Speechreading for Information Gathering

Speechreading for information gathering: A survey of scientific sources1 Ruth Campbell Ph.D, with Tara-Jane Ellis Mohammed, Ph.D Division of Psychology and Language Sciences University College London Spring 2010 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 Questions (and answers) 3 Chronologically organised survey of tests of Speechreading (Tara Mohammed) 4 Further Sources 5 Biographical notes 6 References 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This report aims to clarify what is and is not possible in relation to speechreading, and to the development of speechreading skills. It has been designed to be used by agencies which may wish to make use of speechreading for a variety of reasons, but it focuses on requirements in relation to understanding silent speech for information gathering purposes. It provides the main evidence base for the report : Guidance for organizations planning to use lipreading for information gathering (Ruth Campbell) - a further outcome of this project. 1.2 The report is based on published, peer-reviewed findings wherever possible. There are many gaps in the evidence base. Research to date has focussed on watching a single talker’s speech actions. The skills of lipreaders have been scrutinised primarily to help improve communication between the lipreader (typically a deaf or deafened person) and the speaking hearing population. Tests have been developed to assess individual differences in speechreading skill. Many of these are tabulated below (section 3). It should be noted however that: There is no reliable scientific research data related to lipreading conversations between different talkers. There are no published studies of expert forensic lipreaders’ skills in relation to information gathering requirements (transcript preparation, accuracy and confidence). -

The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 414 CS 504 984 AUTHOR McQuillen, Jeffrey S.;Ivy, Diana K. TITLE The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; Course Content; Course Organization; Educational Assessment; *Educational History; Educational Trends; Higher Education; *Speech Communication; *Speech Curriculum; Speech Instruction ABSTRACT Acknowledging the need for objective evaluation of. the focus and organization of the basic speechcommunication course, this paper reviews the progress of the basic course bytracing its changes and development. The first portion of the paperdiscusses the evolution of the basic course from the 1950s to the present,giving specific attention to historical modifications in thebasic course's orientation and focus. The second, portion of the paperaddresses questions concerning the current orientation,responsiveness, and appropriateness of the basic course, and reviewspromising answers to these questions. (HTH) ********************************************************************** * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** BEST COPY AVAILABLE THE BASIC COURSE IN SPEECH COMMUNICATION: Past, present and r--1 future CT r\J LtJ Jeffrey S. McQuillen Assistant Professor Speech Communication Program Texas ALCM University College Station, TX 77843 (409) 845-8328 Diana K. Ivy Doctoral Candidate Communication Department University of Oklahoma Norman, Ok 73019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL. RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERICI .>\Thisdocument has been reproduced as eceived from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions :riled in this dorm merit do not necessarily represent official NIE position or petit. -

UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

UNITED NATIONS STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Foreword Around the world, we are seeing a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred and persecution of Christians. Social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry. Neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream – in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. As a matter of principle, the United Nations must confront hate speech at every turn. Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims. Tackling hate speech is also crucial to deepen progress across the United Nations agenda by helping to prevent armed conflict, atrocity crimes and terrorism, end violence against women and other serious violations of human rights, and promote peaceful, inclusive and just societies. Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law. The United Nations has a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. -

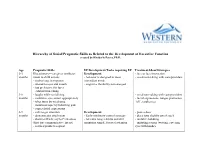

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Analyzing the Rhetoric of JFK's Inaugural Address

Analyzing the Rhetoric of JFK’s Inaugural Address Topic: John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: English Language Arts Time Required: 1-2 class periods Goals/Rationale An inaugural address is a speech for a very specific event—being sworn into the office of the presidency. The speeches of modern presidents share some commonalities in referencing American history, the importance of the occasion, and hope for the future. Each president, however, has faced the particular challenges of his time and put his own distinctive rhetorical stamp on the address. In the course of writing this address, John F. Kennedy and Theodore Sorensen, his advisor and main speechwriter, asked for and received suggestions from advisors and colleagues. (To see the telegram from Ted Sorensen dated December 23, 1960, visit http://tinyurl.com/6xm5m9w.) In his delivered speech, Kennedy included several sections of text provided by both John Kenneth Galbraith, an economics professor at Harvard University and Adlai Stevenson, former governor of Illinois and Democratic presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956. In this lesson plan, students consider the rhetorical devices in the address JFK delivered on January 20, 1961. They then analyze the suggestions made by Galbraith and Stevenson and compare them to the delivered version of the speech. Students then evaluate the impact of the changes on the resonance of the speech. Essential Question: How can the use of rhetorical devices enhance a speech? Objectives Students will: identify rhetorical terms and methods. examine the rhetorical devices of JFK’s inaugural address. analyze the effects of the rhetorical devices on the delivered speech. -

Rethinking Media Richness: Towards a Theory of Media Synchronicity

Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 1999 Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 1999 Rethinking Media Richness: Towards a Theory of Media Synchronicity Alan R. Dennis Joseph S. Valacich Terry College of Business College of Business and Economics University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 Washington State University, Pullman WA 99164 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract compensate for the weak findings and draw new This paper describes a new theory called a theory of conclusions based on the enhancements, or should we media synchronicity which proposes that a set of five attempt formulate a new theory [e.g., 34, 35, 41]? media capabilities are important to group work, and that In this paper, we take the second approach. We all tasks are composed of two fundamental communi- propose a new theory, which we call a theory of media cation processes (conveyance and convergence). synchronicity. The theory proposes that group Communication effectiveness is influenced by matching communication processes, regardless of task outcome the media capabilities to the needs of the fundamental objectives, are composed of two primary processes, communication processes, not aggregate collections of conveyance and convergence. The theory also proposes these processes (i.e., tasks) as proposed by media that media have a set of capabilities that play a dominant richness theory. The theory also proposes that the role when addressing each type of communication relationships between communication processes and process. Performance will be enhanced when media media capabilities will vary between established and capabilities are aligned with these processes. -

Penamerica Principles Oncampus Freespeech

of speech curtailed, there is not, as some accounts have PEN!AMERICA! suggested, a pervasive “crisis” for free speech on campus. Unfortunately, respect for divergent viewpoints has PRINCIPLES! not been a consistent hallmark of recent debates on ma!ers of diversity and inclusion on campus. Though ON!CAMPUS! sometimes overblown or oversimplified, there have been many instances where free speech has been suppressed FREE!SPEECH or chilled, a pa!ern that is at risk of escalating absent concerted action. In some cases, students and univer- sity leaders alike have resorted to contorted and trou- The State of Free Speech on Campus bling formulations in trying to reconcile the principles One of the most talked-about free speech issues in the of free inquiry, inclusivity, and respect for all. There are United States has li"le to do with the First Amendment, also particular areas where legitimate efforts to enable the legislature, or the courts. A set of related controversies full participation on campus have inhibited speech. The and concerns have roiled college and university campuses, discourse also reveals, in certain quarters, a worrisome dis- pi"ing student activists against administrators, faculty, and, missiveness of considerations of free speech as the retort almost as o#en, against other students. The clashes, cen- of the powerful or a diversion from what some consider tering on the use of language, the treatment of minorities to be more pressing issues. Alongside that is evidence and women, and the space for divergent ideas, have shone of a passive, tacit indifference to the risk that increased a spotlight on fundamental questions regarding the role sensitivity to differences and offense—what some call “po- and purpose of the university in American society. -

Effectiveness of Communication Technologies for Distributed Business Meetings

Effectiveness of Communication Technologies for Distributed Business Meetings Willem Standaert 2015 Advisors: Prof. dr. Steve Muylle Prof. dr. Amit Basu Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University, in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Applied Economic Sciences Be true to the game, because the game will be true to you. If you try to shortcut the game, then the game will shortcut you. If you put forth the effort, good things will be bestowed upon you. That's truly about the game, and in some ways that's about life too. Michael Jordan DOCTORAL COMMITTEE Prof. dr. Marc De Clercq Ghent University, Dean Prof. dr. Patrick Van Kenhove Ghent University, Academic Secretary Prof. dr. Steve Muylle Ghent University & Vlerick Business School, Advisor Prof. dr. Amit Basu Cox School of Business, Southern Methodist University, Advisor Prof. dr. Derrick Gosselin Ghent University; University of Oxford & Royal Military Academy of Belgium Prof. dr. Deva Rangarajan Ghent University & Vlerick Business School Prof. dr. Öykü Isik Vlerick Business School Prof. dr. Sirkka Jarvenpaa The University of Texas at Austin Prof. dr. Dov Te’eni Tel Aviv University Business School ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to the people who have contributed to making this dissertation possible. I wish to express my deepest gratitude towards my advisors, Prof. dr. Steve Muylle and Prof. dr. Amit Basu. Without their extensive advice, support, and high-quality input, I could not have brought this dissertation to a successful end. They incited me to reach my full potential and guided me in becoming an independent researcher. -

Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication

Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Ylva Hård af Segerstad Department of Linguistics University of Gothenburg, Sweden 2002 Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Ylva Hård af Segerstad Doctoral Dissertation Publicly defended in Stora Hörsalen, Humanisten, University of Gothenburg, on December 21, 2002, at 10.00, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Göteborg University, Sweden 2002 This volume is a revised version of the dissertation. ISBN 91-973895-3-6 Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Abstract The purpose of the present study is to investigate how written language is used and adapted to suit the conditions of four modes of computer-mediated communication (CMC). Texts from email, web chat, instant messaging and mobile text messaging (SMS) have been analyzed. The general human ability to adapt is deemed to underlie linguistic adaptation. A linguistic adaptivity theory is proposed here. It is proposed that three interdependent variables influence language use: synchronicity, means of expression and situation. Two modes of CMC are synchronous (web chat and instant messaging), and two are asynchronous (email and SMS). These are all tertiary means of expression, written and transmitted by electronic means. Production and perception conditions, such as text input technique, limited message size, as well as situational parameters such as relationship between communicators, goal of interaction are found to influence message composition. The dissertation challenges popular assumptions that language is deteriorating because of increased use in CMC. It is argued that language use in different modes of CMC are variants, or repertoires, like any other variants. -

AI-Mediated Communication: Definition, Research Agenda, and Ethical Considerations

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/jcmc/zmz022/5714020 by Stanford Medical Center user on 31 January 2020 AI-Mediated Communication: Definition, Research Agenda, and Ethical Considerations Jeffrey T. Hancock 1, Mor Naaman 2,3,&KarenLevy 2 1 Department of Communication, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 2 Information Science Department, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA 3 Cornell Tech, Cornell University, New York, NY 10044, USA We define Artificial Intelligence-Mediated Communication (AI-MC) as interpersonal communica- tion in which an intelligent agent operates on behalf of a communicator by modifying, augmenting, or generating messages to accomplish communication goals. The recent advent of AI-MC raises new questions about how technology may shape human communication and requires re-evaluation – and potentially expansion – of many of Computer-Mediated Communication’s (CMC) key theories, frameworks,andfindings.AresearchagendaaroundAI-MCshouldconsiderthedesignofthesetech- nologies and the psychological, linguistic, relational, policy and ethical implications of introducing AI into human–human communication. This article aims to articulate such an agenda. Keywords: Interpersonal Communication, Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Artificial Intelligence-Mediated Communication (AI-MC), Language, Impression Formation, Relationships, Ethics doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmz022 The advent of Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) revolutionized interpersonal commu- nication, providing individuals with a host of formats and channels to send messages and interact with others across time and space (Herring, 2002). In the classic social science understanding of CMC (e.g., Walther & Parks, 2002), the medium and its properties play important roles in modeling how actors use technology to accomplish interpersonal goals. -

The Impacts of Text-Based CMC on Online Social Presence

The Journal of Interactive Online Learning Volume 1, Number 2, Fall 2002 www.ncolr.org ISSN: 1541-4914 The Impacts of Text-based CMC on Online Social Presence Chih-Hsiung Tu George Washington University Abstract Social presence is a critical influence on learners’ online social interaction in an online learning environment via computer-mediated communication (CMC) systems. This study examines how three CMC systems, e-mail, bulletin board, and real-time discussion, influence the level of online social presence and privacy. Mixed methods were applied to examine the relationships of three CMC systems with social presence and privacy. The results indicate (a) E-mail is perceived to possess the highest level of social presence, followed by the real-time discussion and bulletin board; (b) one-to-one e-mail was perceived to have a higher level of privacy while one-to-many was perceived less privacy; and (c) in addition to the attributes of CMC systems, learners’ perceptions of CMC systems impacted level of privacy as well. This study suggested that the format of CMC systems, e-mail and real-time discussion should be examined in two different formats: one-to-one e-mail, one-to-many e-mail, one-to-one real-time discussion, and many-to-many real-time discussion. Social presence is a vital element in influencing online interaction (Fabro & Garrison, 1998; McIsaac & Gunawardena, 1996; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer, 1999). Social presence impacts online interaction (Tu & McIsaac, 2002), user satisfaction (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997), depth of online discussions (Polhemus, Shih, & Swan, 2001), online language learning (Leh, 2001), critical thinking (Tu & Corry, 2002), and Chinese students’ online learning interaction (Tu, 2001).