Training, Warning, and Media Richness Effects on Computer-Mediated Deception and Its Detection Patricia Ann Tilley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speechreading for Information Gathering

Speechreading for information gathering: A survey of scientific sources1 Ruth Campbell Ph.D, with Tara-Jane Ellis Mohammed, Ph.D Division of Psychology and Language Sciences University College London Spring 2010 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 Questions (and answers) 3 Chronologically organised survey of tests of Speechreading (Tara Mohammed) 4 Further Sources 5 Biographical notes 6 References 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This report aims to clarify what is and is not possible in relation to speechreading, and to the development of speechreading skills. It has been designed to be used by agencies which may wish to make use of speechreading for a variety of reasons, but it focuses on requirements in relation to understanding silent speech for information gathering purposes. It provides the main evidence base for the report : Guidance for organizations planning to use lipreading for information gathering (Ruth Campbell) - a further outcome of this project. 1.2 The report is based on published, peer-reviewed findings wherever possible. There are many gaps in the evidence base. Research to date has focussed on watching a single talker’s speech actions. The skills of lipreaders have been scrutinised primarily to help improve communication between the lipreader (typically a deaf or deafened person) and the speaking hearing population. Tests have been developed to assess individual differences in speechreading skill. Many of these are tabulated below (section 3). It should be noted however that: There is no reliable scientific research data related to lipreading conversations between different talkers. There are no published studies of expert forensic lipreaders’ skills in relation to information gathering requirements (transcript preparation, accuracy and confidence). -

An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

An Inefficient Choice: An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ted Michael Dickinson Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Brandon van der Heide Copyrighted by Ted Michael Dickinson 2012 Abstract Media richness theory is frequently cited when discussing the strengths of various media in allowing for immediate feedback, personalization of messages, the ability to use natural language, and transmission of nonverbal cues. Most studies do not, however, address the theory’s main argument that people faced with equivocal message tasks will complete those tasks faster by choosing interpersonal communication media with these features. Participants in the present study either chose or were assigned to a medium and then timed on their completion of an equivocal message task. Findings support media richness theory’s prediction; those using videoconferencing to complete the task did so in less time than those using the leaner medium of text chat. Measures of electronic propinquity, a theory proposing a sense of psychological nearness to others in a mediated communication, were also tested as a potential adjunct to media richness theory’s predictions of medium selection, with mixed results. Keywords: media richness, electronic propinquity, media selection, computer-mediated communication, nonverbal -

The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject

University of North Georgia Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2018 The mpI ortance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject Britton Bailey University of North Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Britton, "The mporI tance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject" (2018). Honors Theses. 33. https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses/33 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the University of North Georgia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of The Degree in Bachelor of Business Administration in Management With Honors Britton G. Bailey Spring 2018 Nonverbal Communication 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Mohan Menon, Dr. Benjamin Garner, and Dr. Stephen Smith for their guidance and advice during the course of this project. Secondly, I would like to thank the many other professors and mentors who have given me advice, not only during the course of this project, but also through my collegiate life. Lastly, I would like to thank Rebecca Bailey, Loren Bailey, Briana Bailey, Kandice Cantrell and countless other friends and family for their love and support. -

Non-Verbal Communication in the Teaching of Polish As a Foreign Language Using the Example of Asian Groups

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS KSZTAŁCENIE POLONISTYCZNE CUDZOZIEMCÓW 25, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/0860-6587.26.03 Między nauczycieleM a uczącyM się: w stronę skutecznej koMunikacji Barbara Morcinek-Abramczyk* https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3843-9652 NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION IN THE TEACHING OF POLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE USING THE EXAMPLE OF ASIAN GROUPS. THE DIFFICULTIES, CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS (THIS article was translated FROM POLISH BY JAKUB WOSIK) Keywords: non-verbal communication, verbal communication, body language, gestures, fore- ign language teacher error, Japanese gestures Abstract. There exists a major gap in the teaching of Polish as a foreign language. It applies to the teaching of extra-verbal communication. It would seem that the acquisition of the extra-verbal code of Polish can occur in students in parallel with the development of their linguistic competence, however, the level of interference between the non-verbal code taken from the country of origin and the code typical for the country of the target language is so high that it distorts communica- tion. That is also just as often the cause of teacher errors caused by a teacher’s lack of awareness that this aspect of communication should also be taught in class. Therefore, this article is intended to indicate those areas to which a teacher should pay particular attention in the teaching process in order to limit as much as possible any communicative problems experienced by students from various cultures. Teachers of Polish as a foreign language devote much time and energy in the educational process to conveying knowledge about Polish grammar, vocabulary, phonetics and culture. -

The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 414 CS 504 984 AUTHOR McQuillen, Jeffrey S.;Ivy, Diana K. TITLE The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; Course Content; Course Organization; Educational Assessment; *Educational History; Educational Trends; Higher Education; *Speech Communication; *Speech Curriculum; Speech Instruction ABSTRACT Acknowledging the need for objective evaluation of. the focus and organization of the basic speechcommunication course, this paper reviews the progress of the basic course bytracing its changes and development. The first portion of the paperdiscusses the evolution of the basic course from the 1950s to the present,giving specific attention to historical modifications in thebasic course's orientation and focus. The second, portion of the paperaddresses questions concerning the current orientation,responsiveness, and appropriateness of the basic course, and reviewspromising answers to these questions. (HTH) ********************************************************************** * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** BEST COPY AVAILABLE THE BASIC COURSE IN SPEECH COMMUNICATION: Past, present and r--1 future CT r\J LtJ Jeffrey S. McQuillen Assistant Professor Speech Communication Program Texas ALCM University College Station, TX 77843 (409) 845-8328 Diana K. Ivy Doctoral Candidate Communication Department University of Oklahoma Norman, Ok 73019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL. RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERICI .>\Thisdocument has been reproduced as eceived from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions :riled in this dorm merit do not necessarily represent official NIE position or petit. -

Children's Sensitivity to Pitch Variation in Language

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Summer 2010 Children's Sensitivity to Pitch Variation in Language Carolyn Quam University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Quam, Carolyn, "Children's Sensitivity to Pitch Variation in Language" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 232. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/232 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/232 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Children's Sensitivity to Pitch Variation in Language Abstract Children acquire consonant and vowel categories by 12 months, but take much longer to learn to interpret perceptible variation. This dissertation considers children’s interpretation of pitch variation. Pitch operates, often simultaneously, at different levels of linguistic structure. English-learning children must disregard pitch at the lexical level—since English is not a tone language—while still attending to pitch for its other functions. Chapters 1 and 5 outline the learning problem and suggest ways children might solve it. Chapter 2 demonstrates that 2.5-year-olds know pitch cannot differentiate words in English. Chapter 3 finds that not until age 4–5 do children correctly interpret pitch cues to emotions. Chapter 4 demonstrates some sensitivity between 2.5 and 5 years to the pitch cue to lexical stress, but continuing difficulties at the older ages. These findings suggest a lateaject tr ory for interpretation of prosodic variation; throughout, I propose explanations for this protracted time-course. -

UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

UNITED NATIONS STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Foreword Around the world, we are seeing a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred and persecution of Christians. Social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry. Neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream – in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. As a matter of principle, the United Nations must confront hate speech at every turn. Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims. Tackling hate speech is also crucial to deepen progress across the United Nations agenda by helping to prevent armed conflict, atrocity crimes and terrorism, end violence against women and other serious violations of human rights, and promote peaceful, inclusive and just societies. Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law. The United Nations has a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. -

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

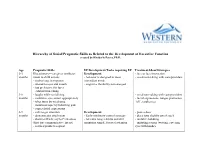

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Different Aspects of Intercultural Nonverbal Communication: a Study

CPUH-Research Journal: 2016, 1(1), 17-24 ISSN (Online): 2455-6076 http://www.cpuh.in/academics/academic_journals.php Different Aspects of Intercultural Nonverbal Communication: A Study Saurabh Kaushal 1School of Humanities & Management Sciences, Career Point University, Hamirpur (HP) INDIA E-mail: [email protected] (Received 05 July, 2015; Accepted 18 July, 2015; Published 03 Mar, 2016) ABSTRACT: Communication is a dynamic and wide process with its ever changing roles of sending and receiving information, ideas, emotions and the working of mind. Communication is not only a word but a term in itself with multiple interpretations. Out of a number of forms, there are two very important kinds of communication, verbal and non-verbal and the relation between them is inseparable. Non-verbal communication keeps the major portion of the periphery occupied and in absence of it communication can never happen. In the era of caveman, just using nonverbal communication could help to understand the other person, but in the complex society of today both ver- bal and non-verbal forms of communication are needed to fully understand each other. We start taking lessons in nonverbal communication from the very starting of our life from parents and the society in which we are surviving. There is a very common perception among people that for understanding any oral message we have to concentrate and subsequently be able to understand the nonverbal elements, but in reality nonverbal communication is not as easy to understand as it seems to be. Often it is misinterpreted and because of that wrong message is understood by the receiver. -

Textual Paralanguage and Its Implications for Marketing Communications†

Textual Paralanguage and Its Implications for Marketing Communications† Andrea Webb Luangratha University of Iowa Joann Peck University of Wisconsin–Madison Victor A. Barger University of Wisconsin–Whitewater a Andrea Webb Luangrath ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the University of Iowa, 21 E. Market St., Iowa City, IA 52242. Joann Peck ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the University of Wisconsin– Madison, 975 University Ave., Madison, WI 53706. Victor A. Barger ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater, 800 W. Main St., Whitewater, WI 53190. The authors would like to thank the editor, associate editor, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback, as well as Veronica Brozyna, Laura Schoenike, and Tessa Strack for their research assistance. † Forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Psychology Abstract Both face-to-face communication and communication in online environments convey information beyond the actual verbal message. In a traditional face-to-face conversation, paralanguage, or the ancillary meaning- and emotion-laden aspects of speech that are not actual verbal prose, gives contextual information that allows interactors to more appropriately understand the message being conveyed. In this paper, we conceptualize textual paralanguage (TPL), which we define as written manifestations of nonverbal audible, tactile, and visual elements that supplement or replace written language and that can be expressed through words, symbols, images, punctuation, demarcations, or any combination of these elements. We develop a typology of textual paralanguage using data from Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We present a conceptual framework of antecedents and consequences of brands’ use of textual paralanguage. -

Dealing with Paralinguistic Features

2012 LINGUA POSNANIENSIS LIV (2) DOI 10.2478/v10122-012-0013-1 THE BOUNDARIES OF LANGUAGE: DEALING WITH PARALINGUISTIC FEATURES MACIEJ KARPIŃSKI ABSTRACT: Maciej Karpiński. The Boundaries of Language: Dealing with Paralinguistic Features. Lin- gua Posnaniensis, vol. LIV (2)/2012. The Poznań Society for the Advancement of the Arts and Sci- ences. PL ISSN 0079-4740, ISBN 978-83-7654-252-2, pp. 37–54. The paralinguistic component of communication attracted a great deal of attention from contemporary linguists in the 1960s. The seminal works written then by Trager, Crystal and others had a powerful in- fl uence on the concept of paralanguage that lasted for many years. But, with the focus shifting towards the socio-psychological context of communication in the 1970s, the development of spoken corpora and databases and the signifi cant progress in speech technology in the 1980s and 1990s, the need has arisen for a more comprehensive, coherent and formalised – but also fl exible – approach to paralinguistic features. This study advances some preliminary proposals for a revised treatment of paralanguage that would meet some of these requirements and provide a conceptual basis for a new system of annota- tion for paralinguistic features. A range of views on paralinguistic features, which come mostly from the fi elds of speech prosody and gesture analysis, are briefl y discussed. A number of assumptions and postulates are formulated to allow for a more consistent approach to paralinguistic features. The study suggests that there should be more reliance on continua than on binary categorisations of features, that multi-functionality and multimodality should be fully acknowledged and that clear distinctions should be made among the levels of description, and between the properties of speakers and the speech signal itself. -

Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication

Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Ylva Hård af Segerstad Department of Linguistics University of Gothenburg, Sweden 2002 Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Ylva Hård af Segerstad Doctoral Dissertation Publicly defended in Stora Hörsalen, Humanisten, University of Gothenburg, on December 21, 2002, at 10.00, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Göteborg University, Sweden 2002 This volume is a revised version of the dissertation. ISBN 91-973895-3-6 Use and Adaptation of Written Language to the Conditions of Computer-Mediated Communication Abstract The purpose of the present study is to investigate how written language is used and adapted to suit the conditions of four modes of computer-mediated communication (CMC). Texts from email, web chat, instant messaging and mobile text messaging (SMS) have been analyzed. The general human ability to adapt is deemed to underlie linguistic adaptation. A linguistic adaptivity theory is proposed here. It is proposed that three interdependent variables influence language use: synchronicity, means of expression and situation. Two modes of CMC are synchronous (web chat and instant messaging), and two are asynchronous (email and SMS). These are all tertiary means of expression, written and transmitted by electronic means. Production and perception conditions, such as text input technique, limited message size, as well as situational parameters such as relationship between communicators, goal of interaction are found to influence message composition. The dissertation challenges popular assumptions that language is deteriorating because of increased use in CMC. It is argued that language use in different modes of CMC are variants, or repertoires, like any other variants.