Speechreading for Information Gathering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

An Inefficient Choice: An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ted Michael Dickinson Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Brandon van der Heide Copyrighted by Ted Michael Dickinson 2012 Abstract Media richness theory is frequently cited when discussing the strengths of various media in allowing for immediate feedback, personalization of messages, the ability to use natural language, and transmission of nonverbal cues. Most studies do not, however, address the theory’s main argument that people faced with equivocal message tasks will complete those tasks faster by choosing interpersonal communication media with these features. Participants in the present study either chose or were assigned to a medium and then timed on their completion of an equivocal message task. Findings support media richness theory’s prediction; those using videoconferencing to complete the task did so in less time than those using the leaner medium of text chat. Measures of electronic propinquity, a theory proposing a sense of psychological nearness to others in a mediated communication, were also tested as a potential adjunct to media richness theory’s predictions of medium selection, with mixed results. Keywords: media richness, electronic propinquity, media selection, computer-mediated communication, nonverbal -

The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 414 CS 504 984 AUTHOR McQuillen, Jeffrey S.;Ivy, Diana K. TITLE The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; Course Content; Course Organization; Educational Assessment; *Educational History; Educational Trends; Higher Education; *Speech Communication; *Speech Curriculum; Speech Instruction ABSTRACT Acknowledging the need for objective evaluation of. the focus and organization of the basic speechcommunication course, this paper reviews the progress of the basic course bytracing its changes and development. The first portion of the paperdiscusses the evolution of the basic course from the 1950s to the present,giving specific attention to historical modifications in thebasic course's orientation and focus. The second, portion of the paperaddresses questions concerning the current orientation,responsiveness, and appropriateness of the basic course, and reviewspromising answers to these questions. (HTH) ********************************************************************** * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** BEST COPY AVAILABLE THE BASIC COURSE IN SPEECH COMMUNICATION: Past, present and r--1 future CT r\J LtJ Jeffrey S. McQuillen Assistant Professor Speech Communication Program Texas ALCM University College Station, TX 77843 (409) 845-8328 Diana K. Ivy Doctoral Candidate Communication Department University of Oklahoma Norman, Ok 73019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL. RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERICI .>\Thisdocument has been reproduced as eceived from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions :riled in this dorm merit do not necessarily represent official NIE position or petit. -

Early Intervention: Communication and Language Services for Families of Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing Children

EARLY INTERVENTION: COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE SERVICES FOR FAMILIES OF DEAF AND HARD-OF-HEARING CHILDREN Our child has a hearing loss. What happens next? What is early intervention? What can we do to help our child learn to communicate with us? We have so many questions! You have just learned that your child has a hearing loss. You have many questions and you are not alone. Other parents of children with hearing loss have the same types of questions. All your questions are important. For many parents, there are new things to learn, questions to ask, and feelings to understand. It can be very confusing and stressful for many families. Many services and programs will be available to you soon after your child’s hearing loss is found. When a child’s hearing loss is identified soon after birth, families and professionals can make sure the child gets intervention services at an early age. Here, the term intervention services include any program, service, help, or information given to families whose children have a hearing loss. Such intervention services will help children with hearing loss develop communication and language skills. There are many types of intervention services to consider. We will talk about early intervention and about communication and language. Some of the services provided to children with hearing loss and their families focus on these topics. This booklet can answer many of your questions about the early intervention services and choices in communication and languages available for you and your child. Understanding Hearing Loss Timing: The age when a hearing loss has occurred is known as “age of onset.” You also might come across the terms prelingual and postlingual. -

UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

UNITED NATIONS STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Foreword Around the world, we are seeing a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred and persecution of Christians. Social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry. Neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream – in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. As a matter of principle, the United Nations must confront hate speech at every turn. Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims. Tackling hate speech is also crucial to deepen progress across the United Nations agenda by helping to prevent armed conflict, atrocity crimes and terrorism, end violence against women and other serious violations of human rights, and promote peaceful, inclusive and just societies. Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law. The United Nations has a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. -

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

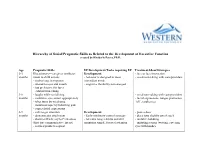

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

In This Issue: Speech Day 10

Soundwave 2016 The Mary Hare Magazine June 2016 maryhare.org.ukmaryhare.org.uk In this issue: Speech Day 10 HRH Princess Royal visits 17 Sports Day 28 Ski Trip 44 Hare & Tortoise Walk 51 Head Boy & Head Girl 18 Primary News 46 SLT & Audiology 53 1 Soundwave 2016 The Mary Hare Magazine June 2016 maryhare.org.uk Acknowledgements Contents Editors, Gemma Pryor and Sammie Wilkinson Looking back and looking forward The Mary Hare Year 4–20 by Peter Gale Getting Active 21–28 Cole’s Diner 29–30 Welcome to this wonderful edition of Soundwave – Mr Peter Gale a real showcase of the breadth and diversity of experiences Arts News 31–33 which young people at Mary Hare get to enjoy. I hope you Helping Others 34–35 will enjoy reading it. People News 35–39 This has been a great year but joined us for our whole school under strict control and while Our Principal one with a real sadness at its sponsored walk/run and a they are substantial, they only Alumni 40–41 heart – the death of a member recent visit from Chelsea allow us to keep going – to of staff. Lesley White made a Goalkeeper Asmir Begovic who pay the wages and heat the Getting Around 42–45 huge contribution to Mary Hare presented us with a cheque school and to try to keep on and there is a tribute to her on for £10,000 means that the top of the maintenance of two Mary Hare Primary School 46–48 page 39. swimming pool Sink or Swim complex campuses. -

Analyzing the Rhetoric of JFK's Inaugural Address

Analyzing the Rhetoric of JFK’s Inaugural Address Topic: John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: English Language Arts Time Required: 1-2 class periods Goals/Rationale An inaugural address is a speech for a very specific event—being sworn into the office of the presidency. The speeches of modern presidents share some commonalities in referencing American history, the importance of the occasion, and hope for the future. Each president, however, has faced the particular challenges of his time and put his own distinctive rhetorical stamp on the address. In the course of writing this address, John F. Kennedy and Theodore Sorensen, his advisor and main speechwriter, asked for and received suggestions from advisors and colleagues. (To see the telegram from Ted Sorensen dated December 23, 1960, visit http://tinyurl.com/6xm5m9w.) In his delivered speech, Kennedy included several sections of text provided by both John Kenneth Galbraith, an economics professor at Harvard University and Adlai Stevenson, former governor of Illinois and Democratic presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956. In this lesson plan, students consider the rhetorical devices in the address JFK delivered on January 20, 1961. They then analyze the suggestions made by Galbraith and Stevenson and compare them to the delivered version of the speech. Students then evaluate the impact of the changes on the resonance of the speech. Essential Question: How can the use of rhetorical devices enhance a speech? Objectives Students will: identify rhetorical terms and methods. examine the rhetorical devices of JFK’s inaugural address. analyze the effects of the rhetorical devices on the delivered speech. -

Research and Evidence 40 Years On

Cued Speech – research and evidence 40 years on In 2016 Cued Speech (CS) celebrates its 40 year anniversary with a conference in America which will be attended by academics and researchers from around the world. In the past 39 years a wide range of evidence has grown which demonstrates its effectiveness and yet there’s still confusion in the minds of many people in the UK as to what exactly CS is. The name ‘Cued Speech’ probably doesn’t help matters. Many people believe that the French name Langage Parlé Complété (LPC) or ‘completed spoken language’ paints a clearer picture and has helped to bring about the situation where every deaf child is offered the option of visual access to French through LPC. CS is a visual version of the spoken language in which it is used. Why then, the name Cued Speech? For hearing children the speech of parents / carers is both how they develop language and the first expression of language, then, when children start school, they have the language they need to learn to read, and then they learn yet more language through reading. For deaf children, CS does the job of speech; it is your speech made visible. When you use the 8 handshapes and 4 positons which are the ‘cues’ of CS, you turn the 44 phonemes of your speech into visible units which can, like sounds, be combined into words, sentences and, as a result, full language. Just as hearing children learn a full language thorough listening to speech, so deaf children can learn a full language through watching speech which is ‘cued’. -

The Language Skills of Singaporean Deaf Children Using Total Communication Mandy Phua Su Yin National University of Singapore 20

THE LANGUAGE SKILLS OF SINGAPOREAN DEAF CHILDREN USING TOTAL COMMUNICATION MANDY PHUA SU YIN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2003 THE LANGUAGE SKILLS OF SINGAPOREAN DEAF CHILDREN USING TOTAL COMMUNICATION MANDY PHUA SU YIN (B.A.(Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL SCIENCE (PSYCHOLOGY) DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WORK AND PSYCHOLOGY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2003 i Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to: ❖ A/P Susan Rickard Liow, Department of Social Work and Psychology, National University of Singapore, for your advice and patient guidance. ❖ The Principal, Mrs Ang-Chang Kah Chai, staff and students of the Singapore School for the Deaf for participating in this study and for teaching me much about the Deaf community. ❖ A/P Low Wong Kein, Head, Department of Otolaryngology, Singapore General Hospital, and colleagues in the Listen and Talk Programme for always being quick to provide instrumental aid. ❖ Ms Wendy Tham and Mr Tracey Evans Chan for your helpful suggestions and comments on the thesis. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Summary viii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Deaf Education Worldwide 1 1.1.1. Definitions and Terminology 1 1.1.2. Language and Literacy 2 1.1.3. Approaches to Deaf Education and Programmes 3 1.1.3.1. Auditory-Verbal Approach 4 1.1.3.2. Bilingual-Bicultural Approach 4 1.1.3.3. Cued Speech 5 1.1.3.4. Oral Approach 5 1.1.3.5. Total Communication 5 1.2. -

Penamerica Principles Oncampus Freespeech

of speech curtailed, there is not, as some accounts have PEN!AMERICA! suggested, a pervasive “crisis” for free speech on campus. Unfortunately, respect for divergent viewpoints has PRINCIPLES! not been a consistent hallmark of recent debates on ma!ers of diversity and inclusion on campus. Though ON!CAMPUS! sometimes overblown or oversimplified, there have been many instances where free speech has been suppressed FREE!SPEECH or chilled, a pa!ern that is at risk of escalating absent concerted action. In some cases, students and univer- sity leaders alike have resorted to contorted and trou- The State of Free Speech on Campus bling formulations in trying to reconcile the principles One of the most talked-about free speech issues in the of free inquiry, inclusivity, and respect for all. There are United States has li"le to do with the First Amendment, also particular areas where legitimate efforts to enable the legislature, or the courts. A set of related controversies full participation on campus have inhibited speech. The and concerns have roiled college and university campuses, discourse also reveals, in certain quarters, a worrisome dis- pi"ing student activists against administrators, faculty, and, missiveness of considerations of free speech as the retort almost as o#en, against other students. The clashes, cen- of the powerful or a diversion from what some consider tering on the use of language, the treatment of minorities to be more pressing issues. Alongside that is evidence and women, and the space for divergent ideas, have shone of a passive, tacit indifference to the risk that increased a spotlight on fundamental questions regarding the role sensitivity to differences and offense—what some call “po- and purpose of the university in American society. -

Speech Communication

SPEECH COMMUNICATION Associate of Art / Associate of Science degree Program and Career Description: The Speech Communication emphasis is a two-year program for students planning to complete a bachelor’s degree in Communications, Speech, or Public Relations. Students pursuing careers in public relations, advertising, law, speech writing, liaison, customer service, or corporate communications should consider this degree. Below are a few examples of career and salary estimates. Career Entry-Level Education Entry-Level Pay Median Pay Experienced Pay Advertising and Promotions Bachelor’s degree $40,720 $66,400 $102,450 Managers Arbitrators, Mediators, and Bachelor’s degree $35,520 $55,790 $68,340 Conciliators Communications Teachers, Master’s degree or $31,720 $48,700 $62,830 Postsecondary Doctoral degree Career and salary information taken from JOBS4TN.GOV. Check out this website for additional information about job de- scriptions, education requirements and abilities, and supply and demand for these careers. For additional information from a national perspective, go to Bureau of Labor Statistics, U. S. Department of Labor on the internet at www.bls.gov. Visit the Occupational Outlook Handbook on this website. Salaries are not guaranteed. Transfer Options This program is a Tennessee Transfer Pathway (TTP) major. A student who completes the associates degree in this major is guaranteed that all required community college courses will be accepted in this major at the transfer institution. To see which four-year institutions offer this TTP major and guarantees a seamless transfer, visit the Tennessee Transfer Pathway website at www.tntransferpathway.org. Articulation agreements exist between other private and non-TN public institutions. -

Speech Communication? the University of Georgia Career Center Clark Howell Hall, 706-542-3375

What can I do with a major in Speech Communication? The University of Georgia Career Center Clark Howell Hall, 706-542-3375, www.career.uga.edu Speech Communication Department, 706-542-4893, www.uga.edu/~spc/ The information below describes typical occupations and employers associated with this major. Understand that some of the options listed below may require additional training. Moreover, you are not limited to these options alone when choosing a possible career path. Description of Speech Communication Speech Communication is a branch of the liberal arts that seeks to develop skills in individual oral and written expression, critical thinking, group discussion, problem solving, and conceptualizing functions of communication. Speech Communication majors receive instruction in interpersonal and public communication, as well as acquire an understanding of both theory and application. The knowledge of application, theory, and research gained from a major in Speech Communication is a valuable foundation for any career. Graduates in Speech Communication can pursue careers in government agencies, courtrooms, political campaigns, social movements, personnel offices, organizational management, sales, corporate education, training, or public relations. This is also excellent preparation for law school, business school, or other professional and graduate training. Possible Job Titles (*As reported by Career Center post-graduate survey) Account Manager* Editor* Project Manager* Admissions Representative* Event Planner* Purchasing Agent* Alcohol