The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's First Language Acquisition

School of Humanities Department of English Children’s first language acquisition What is needed for children to acquire language? BA Essay Erla Björk Guðlaugsdóttir Kt.: 160790-2539 Supervisor: Þórhallur Eyþórsson May 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Anatomy 5 2.1 Language production areas in the brain 5 2.2. Organs of speech and speech production 6 3 Linguistic Nativism 10 3.1 Language acquisition device (LAD) 11 3.2 Universal Grammar (UG) 12 4 Arguments that support Chomsky’s theory 14 4.1 Poverty of stimulus 14 4.2 Uniformity 15 4.3 The Critical Period Hypothesis 17 4.4 Species significance 18 4.5 Phonological impairment 19 5 Arguments against Chomsky’s theory 21 6 Conclusion 23 References 24 Table of figures Figure 1 Summary of classification of the organs of speech 7 Figure 2 The difference between fully grown vocal tract and infant's vocal tract 8 Figure 3 Universal Grammar’s position within Chomsky’s theory 13 Abstract Language acquisition is one of the most complex ability that human species acquire. It has been a burning issue that has created tension between scholars from various fields of professions. Scholars are still struggling to comprehend the main factors about language acquisition after decades of multiple different theories that were supposed to shed a light on the truth of how human species acquire language acquisition. The aim of this essay is to explore what is needed for children to acquire language based on Noam Chomsky theory of language acquisition. I will cover the language production areas of the brain and how they affect language acquisition. -

Your Pace Or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 1-2006 Your Pace or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation Ian MACDUFF Singapore Management University, [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2006.00084.x Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Citation MACDUFF, Ian. Your Pace or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation. (2006). Negotiation Journal. 22, (1), 31-45. Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/879 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Published in Negotiation Journal, Volume 22, Issue 1, January 2006, Pages 31-45. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2006.00084.x Your Pace or Mine? Culture, Time, and Negotiation Ian Macduff This article explores the impact that different perceptions of time may have on cross-cultural negotiations. Beyond obvious issues of punc- tuality and timekeeping, differences may occur in the value placed on the uses of time and the priorities given to past, present, or future ori- entations. -

The Importance of the Body Language and the Non-Verbal Signals in the Courtroom in the Criminal Proceedings

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 112 (2018) 74-84 EISSN 2392-2192 The importance of the body language and the non-verbal signals in the courtroom in the criminal proceedings. The outline of the problem Agnieszka Gurbiel Faculty of Law and Administration, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Cracow, Poland E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT This publication defines and characterizes the body language and tries to show its place and its role in the courtroom in the criminal proceedings. According to Albert Mehrabian - one of the first researchers of the body language - only 7% are affected by the words, 38% by the voice signals (the voice tone, the modulation) and 55% by the non-verbal signals. In view of the above fact it follows that the skills of the effective occurrence pay off so are the considerations in this context justified? Keywords: the body language, the courtroom, the criminal proceedings 1. INTRODUCTION The body language "can not be completely stopped", i.e. the non-verbal signals are "continuous and common" [1]. The criminal proceedings are also the process of the providing information by means of the non-language meanings.This is a compilation of, for example, an appearance, an outfit, a posture, a way of moving, the gestures, the facial expressions. The public is convinced that the case wins the court which will present the best evidence. However, a lawyer or a solicitor who once served as a defender or an attorney for a long time knows that the non-verbal communication interaction which takes place in the ( Received 14 September 2018; Accepted 29 September 2018; Date of Publication 30 September 2018 ) World Scientific News 112 (2018) 74-84 courtroom often turns out to be the most important force [2, 3]. -

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

Body Language As a Communicative Aid Amongst Language Impaired Students: Managing Disabilities

English Language Teaching; Vol. 14, No. 6; 2021 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Body Language as a Communicative Aid amongst Language Impaired Students: Managing Disabilities Nnenna Gertrude Ezeh1, Ojel Clara Anidi2 & Basil Okwudili Nwokolo1 1 The Use of English Unit, School of General Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka (Enugu Campus), Nigeria 2 Department of Language Studies, School of General Studies, Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria Correspondence: Nnenna Gertrude Ezeh, C/o Department of Theology, Bigard Seminary Enugu. P.O. Box 327, Uwani- Enugu, Nigeria. Received: April 10, 2021 Accepted: May 28, 2021 Online Published: May 31, 2021 doi: 10.5539/elt.v14n6p125 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v14n6p125 Abstract Language impairment is a condition of impaired ability in expressing ideas, information, needs and in understanding what others say. In the teaching and learning of English as a second language, this disability poses a lot of difficulties for impaired students as well as the teacher in the pedagogic process. Pathologies and other speech/language interventions have aided such students in coping with language learning; however, this study explores another dimension of aiding impaired students in an ESL situation: the use of body language. The study adopts a quantitative methodology in assessing the role of body language as a learning tool amongst language/speech impaired students. It was discovered that body language aids students to manage speech disabilities and to achieve effective communication; this helps in making the teaching and learning situation less cumbersome. Keywords: body language, communication, language and speech impairment, English as a second language 1. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

The Visual Perception of Dynamic Body Language Maggie Shiffrar

05-Wachsmuth-Chap05 4/21/08 3:24 PM Page 95 5 The visual perception of dynamic body language Maggie Shiffrar 5.1 Introduction Traditional models describe the visual system as a general-purpose processor that ana- lyzes all categories of visual images in the same manner. For example, David Marr (1982) in his classic text Vision described a single, hierarchical system that relies solely on visual processes to produce descriptions of the outside world from retina images. Similarly, Roger N Shepard (1984) understood the visual perception of motion as dependent upon the same processes no matter what the image. As he eloquently proposed, “There evi- dently is little or no effect of the particular object presented. The motion we involuntarily experience when a picture of an object is presented first in one place and then in another, whether the picture is of a leaf or of a cat, is neither a fluttering drift nor a pounce, it is, in both cases, the same simplest rigid displacement” (p. 426). This traditional approach presents a fruitful counterpoint to functionally inspired models of the visual system. Leslie Brothers (1997), one of the pioneers of the rapidly expanding field of Social Neuroscience, argued that the brain is primarily a social organ. As such, she posited that neurophysiologists could not understand how the brain functions until they took into consideration the social constraints on neural development and evolution. According to this view, neural structures are optimized for execution and comprehension of social behavior. This raises the question of whether sensory systems process social and non- social information in the same way. -

Different Aspects of Intercultural Nonverbal Communication: a Study

CPUH-Research Journal: 2016, 1(1), 17-24 ISSN (Online): 2455-6076 http://www.cpuh.in/academics/academic_journals.php Different Aspects of Intercultural Nonverbal Communication: A Study Saurabh Kaushal 1School of Humanities & Management Sciences, Career Point University, Hamirpur (HP) INDIA E-mail: [email protected] (Received 05 July, 2015; Accepted 18 July, 2015; Published 03 Mar, 2016) ABSTRACT: Communication is a dynamic and wide process with its ever changing roles of sending and receiving information, ideas, emotions and the working of mind. Communication is not only a word but a term in itself with multiple interpretations. Out of a number of forms, there are two very important kinds of communication, verbal and non-verbal and the relation between them is inseparable. Non-verbal communication keeps the major portion of the periphery occupied and in absence of it communication can never happen. In the era of caveman, just using nonverbal communication could help to understand the other person, but in the complex society of today both ver- bal and non-verbal forms of communication are needed to fully understand each other. We start taking lessons in nonverbal communication from the very starting of our life from parents and the society in which we are surviving. There is a very common perception among people that for understanding any oral message we have to concentrate and subsequently be able to understand the nonverbal elements, but in reality nonverbal communication is not as easy to understand as it seems to be. Often it is misinterpreted and because of that wrong message is understood by the receiver. -

DDE Syllabuses

ORDINANCE, SCHEME OF EXAMINATION & SYLLABI FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION PROGRAMMES DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION MAHARSHI DAYANAND UNIVERSITY, ROHTAK (HARYANA) INDIA EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Dr. Narender Kumar Director Directorate of Distance Education M.D.University, Rohtak (India) Phone: 01262393189 & Professor & Head Department of Commerce, M.D.University, Rohtak (India) Dr. Rajpal Singh Associate Professor Department of Commerce M.D.University, Rohtak (India) & Coordinator Directorate of Distance Education M.D.University, Rohtak (India) Phone: 01262393187 Dr. Gopal Singh Assistant Professor Department of Computer Science & Applications M.D.University, Rohtak (India) & Coordinator Directorate of Distance Education M.D.University, Rohtak (India) Phone: 01262393187 Dr. M.M. Kaushik Officer on Special Duty Directorate of Distance Education M.D.University, Rohtak (India) Phone: 01262393192 TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Sh. S.L Gupta Supdt., Directorate of Distance Education Sh. Satish Sharma, Foreman, Directorate of Distance Education Pankaj Malik, clerk cum Jr. DEO, Directorate of Distance Education Rajbir Singh, Compositor, Directorate of Distance Education First Edition: July 2011 Copyright © M.D.University, Rohtak Contents ORDINANCE 5-13 Scheme of Examination 1. Bachelor of Arts (BA) 14 2. Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com) 17 3. Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) 19 4. Bachelor of Computer Applications (BCA) 21 5. Bachelor of Hotel Management (BHM) 23 6. Bachelor of Tourism Management (BTM) 24 7. Bachelor of Science (Animation & Multimedia) 25 8. Bachelor of Science (Interior Design) B.Sc. (ID) 27 9. Bachelor of Arts (Performing Arts) B.A. (PA) 29 10. Bachelor of Arts (Fine Arts) B.A. (FA) 31 11. Bachelor of Arts (YOGA) 33 12. Bachelor of Journalism & Mass Communication (B.J.M.C.) 34 13. -

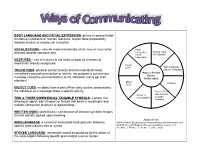

Body Language and Facial Expression

BODY LANGUAGE AND FACIAL EXPRESSION: physical representation to internal (emotional or mental) reactions, maybe done purposefully towards another or maybe just a reaction VOCALIZATIONS – sounds made intentionally which may or may not be Body directed towards someone else Language / Written Word Facial (Print/Braille) Expression GESTURES – use of motions of the limbs or body as a means of expression socially recognized Touch Cues Sign Language / TOUCH CUES: physical contact directly onto the individuals body Spoken Language immediately preceding an action or activity, the purpose is conveying a Ways a Person Can be message (receptive communication) to the individual (not to get their Understood attention) Object Pictures Cues OBJECT CUES: an object from a part of their daily routine, presented to the individual as a message about a specific activity. Two or Three- dimensional Gestures Vocalizations Tangible TWO & THREE-DIMENSIONAL TANGIBLE SYMBOLS: a photo, line Symbols drawing or object/ part of object or texture that bears a meaningful and realistic connection to what it is representing. WRITTEN WORD (print/Braille): combination of abstract symbolic shapes to have socially agreed upon meaning Adapted from SIGN LANGUAGE: a system of articulated hand gestures following Hand In Hand: Essenstials of communication and Orientation and specific grammatical rules or syntax Mobility for your Students Who are deaf-Blind, Volume I.; K. Huebner, J. Prickett, T. Welch, E. Joffee:1995. SPOKEN LANGUAGE: meaningful sound as produced by the action of the vocal organs following specific grammatical rules or syntax Receptive Expressive Ways ____ Ways others understands understand others ____________ Identify the ways people Identify the ways _______ gets communicate with ______ so others to understand him/her. -

Improving Communication Based on Cultural

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2011 IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Patricia Darlington, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies, and has been approved by the members ofhis supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~o--b Patricia Darlington, Ph.D. ~.:J~~ Nannetta Durnell-Uwechue, Ph.D. ~~C-~ Arthur S. E ans, J. Ph.D. c~~~Q,IL---_ Emily~ard, Ph.D. Director, Comparative Studies Program ~~~ M~,Ph.D. Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College ofArts & Letters ~~~~ Dean, Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee Prof. Patricia Darlington, Prof. Nennetta Durnell-Uwechue, Prof. Arthur Evans, and Prof. Angela Rhone for your diligent readings of my work as well as your limitless dedication to the art of teaching. I would like to offer a special thanks to my Chair Prof. Patricia Darlington for your counsel in guiding me through this extensive and arduous project. I speak for countless students when I say that over the past eight years your inspiration, guidance, patience, and encouragement has been a constant beacon guiding my way through many perils and tribulations, along with countless achievements and accomplishments. -

Bachelor of Science in Chemistry

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN CHEMISTRY (Honours) CURRICULUM AND SYLLABUS (For Students admitted from academic year 2018 – 2019 onwards) UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM Sri Ramasamy Memorial University, Sikkim 5th Mile, Tadong, Gangtok, Sikkim 737102 B.Sc. Chemistry (For students admitted from the academic year 2018–2019 onwards) CURRICULUM AND SYLLABUS Objectives: 1. To help the students to acquire a comprehensive knowledge and sound understanding of fundamentals of Chemistry. 2. To develop practical and analytical skills of Chemistry. 3. To prepare students to acquire a range of general skills, to solve problems, to evaluate information, to use computers productively, to communicate with society effectively and learn independently. 4. To enable them to acquire a job efficiently in diverse fields such as Science and Engineering, Education, Banking, Public Services, Business etc., Eligibility: The candidates seeking admission to the B.Sc. Degree program shall be required to have passed (10+2) (Higher Secondary) examination or any other equivalent examination of any authority, recognized by this University, with Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics/Biosciences. Duration: 3 Years (6 Semesters) SCHEME AND SYLLABUS FOR CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM FOR B.Sc. CHEMISTRY CURRICULUM Core course Ability Skill Discipline Specific Enhancement Enhancement Elective Compulsory Course Course SEM I 1. Structure and Bonding in English LASR 1. Basic Chemistry Computer 2. States of Matter and Ionic skills equilibria 2. Environmental Studies SEM II1. 1. Thermodynamics, Chemical English C-programming Equilibrium, Solutions and communication language Colligative Properties 2. 2. Basic Concepts of Organic Chemistry SEM 1. General Principles of Food III Metallurgy, Acids and Bases, Chemistry and Main Group Elements, Inorganic Analysis life Polymers.