Graham Greene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism Christopher Wachal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wachal, Christopher, "Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism" (2011). Dissertations. 181. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Christopher Wachal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PAX ECCLESIA: GLOBALIZATION AND CATHOLIC LITERARY MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY CHRISTOPHER B. WACHAL CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Christopher B. Wachal, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nothing big worth undertaking is undertaken alone. It would certainly be dishonest for me to claim that the intellectual journey of which this text is the fruition has been propelled forward solely by my own energy and momentum. There have been many who have contributed to its completion – too many, perhaps, to be done justice in so short a space as this. Nonetheless, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to some of those whose assistance I most appreciate. My dissertation director, Fr. Mark Bosco, has been both a guide and an inspiration throughout my time at Loyola University Chicago. -

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

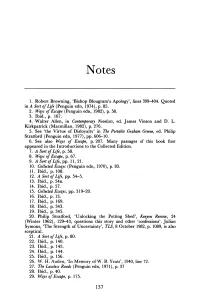

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

Moral Values in Espionage Novels by Graham Greene

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Viktoria Fedorova Moral Values In Espionage Novels by Graham Greene Bachelor's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2017 / declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Viktória Fedorová 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for all his valuable advice. I would also like to thank my family, my partner and my friends for their support. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Graham Greene: Life and Vision 10 2.1. Espionage 15 2.2. Greene and Catholicism 17 2.3. The Entertainments and "Serious Novels" 21 3. The Ministry of Fear 23 4. The Quiet American 32 5. The Comedians 46 6. Conclusion °1 7. Works Cited 65 8. Resume (English) 67 9. Resume (Czech) 68 4 1. Introduction The aim of this thesis is to analyse and compare the treatment of moral values in three espionage novels by Graham Greene- The Ministry of Fear, The Quiet American and The Comedians- to show that the debate of moral values in Greene's novels is closely connected with the notion that the gravity of sins committed is connected to the amount of pain one's decision causes to other human beings. The evil committed by his characters is to be judged individually and one of his characters' greatest fears is the fear to cause the pain to other human beings. Espionage novels were used because Greene's experience with espionage is often projected into his novels and it is often central to the plot. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene Stephen D. Arata College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arata, Stephen D., "The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625259. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6j1s-0j28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mystery of Evil // in Five Works by Graham Greene A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Stephen D. Arata 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts /;. WiaCe- Author Approved, September 1984 ABSTRACT Graham Greene's works in the 1930s reveal his obsession with the nature and source of evil in the world. The world for Greene is a sad and frightening place, where betrayal, injustice, and cruelty are the norm. His books of the 1930s, culminating in Brighton Rock (1938), are all, on some level, attempts to explain why this is so. -

1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 Am Introduction

THE MINISTRY OF FEAR AN ENTERTAINMENT Grahame Greene Introduction by richard greene Coeor’s LıBrarY 3 1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 am Introduction Spies, fugitives, double-agents, traitors, informers: Graham Greene seemed to carry these stock characters of fiction inside his skin. His imagination endowed them with moral urgency. He found in the plots of the common thriller, its concealments and duplicities, the elements of a more universal tale. His characters become the agents of the divided heart and their yearning for safety, escape, refuge, becomes a fable of the modern world. Graham Greene’s childhood would have divided any heart. Born in 1904, he was the son of a master (later headmaster) of Berkhamsted School in Hert- fordshire. After a quiet childhood, he was sent at the age of thirteen to live as a boarder in the school. This placed him on the other side of a symbolic green baize door which separated the family quarters from the school. The other boys assumed he was a Judas, reporting to his father all that happened in the dormitory. Two of his friends subjected him to elaborate mental cruelties, which he recalled as torture. Greene fell apart, made attempts at suicide, and eventually ran away to Berkhamsted Common, intending to become, as he wrote in his autobio- graphy, A Sort of Life (1971), ‘an invisible watcher, a spy on all that went on’. His parents brought him back into the family quarters, but he was never the same. In a family with a devastating history of mental illness, he showed signs of depression and instability.