Book Reviews 329 Reference Cited Jones, Stephen. Plucking the Winds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composer Performer

Capital Normal University is well-known for its role in educational and cultural transmission and innovation in China. It has set up various departments and offers complete sets of academic disciplines, including liberal arts, science, engineering, management, law, education, art, music and foreign languages etc.. It has also opened many research fields with unique oriental cultural characteristics. Music College of CNU is one of the most famous music schools in China. It comprises 7 departments serving undergraduate and graduate degrees in music education, composing, conducting, piano, vocal, Chinese and western musical instruments, recording technique, dancing,. It also serving doctoral degrees of music education, composing, theory of composing, musicology, music science as well as dancing. The Music College has its chorus troupe, national music band, Chinese and western chamber music band and dancing troupe. Composer Yangqing: Famous composer of Zhou Xueshi: composer,Professor of China. Professor, Dean of Music College Music College of CNU. of CNU. His works involves orchestral <New arrangement: Birds in the Shade>, music, chamber music, dance drama for Chinese Flute, Sheng, Xun, Pipa, Erhu and movie music, His music win a high and Percussion. The musical materials of admiration in china. Leader of this this piece originate from this work—Birds visiting group to USA. Special invited in the Shade for Chinese Flute Solo by to compose a piece of music for both Guanyue Liu. It presents an interesting Chinese and USA instrumentalists. counterpoint in ensemble and shows the technical virtuosity of performers by developing fixed melody patterns and sound patterns. Performer Zhou Shibin: Vice dean, professor Wang Chaohui: Pipa performer . -

Instrument List

Instrument List Africa: Europe: Kora, Domu, Begana, Mijwiz 1, Mijwiz 2, Arghul, Celtic & Wire Strung Harps, Mandolins, Zitter, Ewe drum collection, Udu drums, Doun Doun Collection of Recorders, Irish and other whistles, drums, Talking drums, Djembe, Mbira, Log drums, FDouble Flutes, Overtone Flutes, Sideblown Balafon, and many other African instruments. Flutes, Folk Flutes, Chanters and Bagpipes, Bodran, Hang drum, Jews harps, accordions, China: Alphorn and many other European instruments. Erhu, Guzheng, Pipa, Yuequin, Bawu, Di-Zi, Guanzi, Hulusi, Sheng, Suona, Xiao, Bo, Darangu Middle East: Lion Drum, Bianzhong, Temple bells & blocks, Oud, Santoor, Duduk, Maqrunah, Duff, Dumbek, Chinese gongs & cymbals, and various other Darabuka, Riqq, Zarb, Zills and other Middle Chinese instruments. Eastern instruments. India: North America: Sitar, Sarangi, Tambura, Electric Sitar, Small Banjo, Dulcimer, Zither, Washtub Bass, Native Zheng, Yuequin, Bansuris, Pungi Snake Charmer, Flute, Fife, Bottle Blows, Slide Whistle, Powwow Shenai, Indian Whistle, Harmonium, Tablas, Dafli, drum, Buffalo drum, Cherokee drum, Pueblo Damroo, Chimtas, Dhol, Manjeera, Mridangam, drum, Log drum, Washboard, Harmonicas Naal, Pakhawaj, Tamte, Tasha, Tavil, and many and more. other Indian instruments. Latin America: Japan: South American & Veracruz Harps, Guitarron, Taiko Drum collection, Koto, Shakuhachi, Quena, Tarka, Panpipes, Ocarinas, Steel Drums, Hichiriki, Sanshin, Shamisen, Knotweed Flute, Bandoneon, Berimbau, Bombo, Rain Stick, Okedo, Tebyoshi, Tsuzumi and other Japanese and an extensive Latin Percussion collection. instruments. Oceania & Australia: Other Asian Regions: Complete Jave & Bali Gamelan collections, Jobi Baba, Piri, Gopichand, Dan Tranh, Dan Ty Sulings, Ukeleles, Hawaiian Nose Flute, Ipu, Ba,Tangku Drum, Madal, Luo & Thai Gongs, Hawaiian percussion and more. Gedul, and more. www.garritan.com Garritan World Instruments Collection A complete world instruments collection The world instruments library contains hundreds of high-quality instruments from all corners of the globe. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

The Music of Bright Sheng: Expressions of Cross-Cultural Experience

The Music of Bright Sheng: Expressions of Cross-Cultural Experience Introduction: The idea of tapping non-Western compositional resources in Twentieth- century works is not new. With its beginning in Europe, it came to America in the mid-Twentieth century. Quite a few American avant-garde composers have tried to infuse Eastern elements in their works either by direct borrowing of melodic material or philosophical concepts. As a whole, these composers have challenged the American musical community to recognize cultural differences by finding the artistic values in this approach. Since the mid-1980s, Chou Wen- Chung, a champion of East-West musical synthesis, recruited a group of prize- winning young Chinese composers through his U.S.-China Arts Exchange to study at Columbia University. Most of these composers such as Tan Dun, Bright Sheng, Chen Yi, Zhou Long, Ge Gan-ru, Bun-Ching Lam had solid conservatory training before coming to the United States. They are now in their early 50s, and are successful in their individual careers, and are contributing a great deal for the musical life in America. Writing an article about this “Chinese phenomenon,” James Oestereich notes that although the American musical community has been slow to accepted this fact, “all of these composers tend to be marginalized at times, their cross-cultural works treated as novelties rather than a part of the contemporary-music mainstream (if mainstream there be anymore).” 1 Oestereich cites an example that, “in all the criticism of a paucity of contemporary music at the New York Philharmonic in recent years, Mr. Masur seldom receives points for his advocacy of some of these composers and others of Asian heritage.”2 This article was published five years ago. -

Understanding of Authentic Performance Practice in Bright Sheng’S Seven Tunes Heard in China for Solo Cello

UNDERSTANDING OF AUTHENTIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE IN BRIGHT SHENG’S SEVEN TUNES HEARD IN CHINA FOR SOLO CELLO A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Chiao-Hsuan Kang B.F.A., National Taiwan Normal University, 2009 M.M., College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 2012 May 2016 © [2016 copyright] [Chiao-Hsuan Kang] All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my heart-felt appreciation to my parents, Chen Min Kang and Mei Yuan Lin for their support, love and encouragement during my many years of education, both in Taiwan and in the United States. I would like to thank the composer, Bright Sheng for his insightful and helpful indications during the process of learning this music and preparing this document. I am also deeply indebted to the members of my Doctor of Musical Arts committee, Jan Grimes, who has been unwavering in her positive support and emotional strength, Robert Peck, who always has had the patience and ability to keep me from worrying more than necessary, Gang Zhou for her careful reading and participation in this project, and Dennis Parker, my major professor during my three years at Louisiana State University, who has been much more than merely a cello teacher, and has helped open my eyes to many other areas of art and life. There have been many wonderful teachers and mentors here and elsewhere from whom I have gathered inspiration, and with whom I have had marvelous performance opportunities. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Canadian Oboe Concertos

An Annotated Bibliography of Canadian Oboe Concertos Document Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe in the Performance Studies Division of the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music January 11, 2016 by Elizabeth E. Eccleston M02515809 B.M., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 D.M.A. Candidacy: April 5, 2012 256 Major Street Toronto, Ontario M5S 2L6 Canada [email protected] ____________________________ Dr. Mark Ostoich, Advisor ____________________________ Dr. Glenn Price, Reader ____________________________ Professor Lee Fiser, Reader Copyright by Elizabeth E. Eccleston 2016 i Abstract: Post-World War II in Canada was a time during which major organizations were born to foster the need for a sense of Canadian cultural identity. The Canada Council for the Arts, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Music Centre led the initiative for commissioning, producing, and disseminating this Canadian musical legacy. Yet despite the wealth of repertoire created since then, the contemporary music of Canada is largely unknown both within and outside its borders. This annotated bibliography serves as a concise summary and evaluative resource into the breadth of concertos and solo works written for oboe, oboe d’amore, and English horn, accompanied by an ensemble. The document examines selected pieces of significance from the mid-twentieth century to present day. Entries discuss style and difficulty using the modified rating system developed by oboist Dr. Sarah J. Hamilton. In addition, details of duration, instrumentation, premiere/performance history, including dedications, commissions, program notes, reviews, publisher information and recordings are included wherever possible. -

The Interaction of Cello and Chinese Traditional Music

The Interaction of Cello and Chinese Traditional Music BY LAN JIANG Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Dr. Paul Laird Mr. Edward Laut Mr. David Leslie Neely Dr. Martin J. Bergee Dr. Bryan Kip Haaheim Defense Date: May 25, 2017 i The Dissertation Committee for Lan Jiang certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Interaction of Cello and Chinese Traditional Music Chairperson Dr. Paul Laird Date approved: May 30, 2016 ii Abstract This document concerns the interaction of the cello and Chinese traditional music with an emphasis on three major areas. An historical introduction to western music in China includes descriptions of its early appearances and development, musical education influences, and how the cello became an important instrument in China. The second section is a discussion of techniques of western music and Chinese traditional music as used by Chinese composers, who write works in both styles separately and in admixtures of the two. The third section is a description of four Chinese works that include cello: “《二泉印月》” (Reflection of Moon in Er-Quan Spring), 《“ 川腔》” (The Voice of Chuan), “《渔舟唱晚》” (The Melodies of the Fishing Night), and “《对话集 I》” (Dialogue I). Analysis of these four works helps show how the cello has been assimilated into Chinese traditional music in both solo and ensemble fields, with specific looks at incorporating traditional performing techniques on the cello, the imitation of programmatic themes and aspects of Chinese culture in such works, and complex issues concerning aspects of performance. -

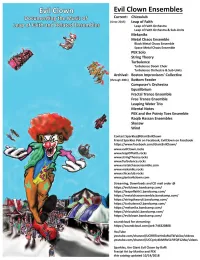

Evil Clown Ensembles

~wtj~ ~~@WITD Evil Clown Ensembles ~~Utffi OOL@ ~~ ®} Current: Chicxulub (since 2015} Leap of Faith ~~ ®} [f@flOOo ~[nXg] ~ ~~ Leap of Faith Orchestra Leap of Faith Orchestra & Sub-Units Mekaniks Metal Chaos Ensemble Black Metal Chaos Ensemble Space Metal Chaos Ensemble PEK Solo String Theory Turbulence Turbulence Doom Choir Turbulence Orchestra & Sub-Units Archival: Boston lmprovisors' Collective (through 2001) Bottom Feeder Composer's Orchestra Equalibrium Fractal Trance Ensemble Free Trance Ensemble Leaping Water Trio Mental Notes PEK and the Pointy Toes Ensemble Raqib Hassan Ensembles Skysaw Wind Contact Sparkles@GiantEvilClown Friend Sparkles Pek on Facebook, EvilClown on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/GiantEvilClown/ www.evilClown.rocks www.leapOfFaith.rocks www.stringTheory.rocks www.Turbulence.rocks www.metalchaosensemble.com www.mekaniks.rocks www.chicxulub.rocks www.giantevilclown.com Streaming, Downloads and CD mail order @ https://evilclown.bandcamp.com/ https://leapoffaithl.bandcamp.com/ https://metalchaosensemble.bandcamp.com/ https://stringtheory6.bandcamp.com/ https://turbulence2.bandcamp.com/ https://mekaniks.bandcamp.com/ https://chicxulubl.bandcamp.com/ https://evilclown.bandcamp.com/ soundcloud for streaming: https://soundcloud.com/pek-746320808 YouTube youtube.com/channel/UClfRITeeHnSxRsJTkFakiJw/videos youtube.com/channel/UCCprJy4kMIRs51FIFQF12dw/videos Sparkles, the Giant Evil Clown by Raffi Fractal Art by Martha and PEK this catalog updated 10/14/2018 Boston Improvisors' Collective Audio CD Evil Clown 5002 Boston -

A Chinese New Year Concert with the Orchestra Now

US-CHINA MUSIC INSTITUTE OF THE BARD COLLEGE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC CENTRAL CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC, CHINA THE SOUND OF SPRING A CHINESE NEW YEAR CONCERT WITH THE ORCHESTRA NOW JANUARY 25 AND 26, 2020 SOSNOFF THEATER, FISHER CENTER AT BARD COLLEGE ROSE THEATER, JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER’S FREDERICK P. ROSE HALL Welcome to the first annual Chinese New Year concert with The Orchestra Now, presented by the US-China Music Institute of the Bard College Conservatory of Music. This is a happy, optimistic time of year to honor family and wish one another good fortune, while enjoying the season’s many THE SOUND OF SPRING traditions. I am delighted that you have chosen to join us for today’s celebration. A CHINESE NEW YEAR CONCERT WITH THE ORCHESTRA NOW This year’s program, The Sound of Spring, features many extraordinary musicians on the distinguished faculty of our copresenter, the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, China. I would like to thank Saturday, January 25 at 7 pm President Yu Feng of the Central Conservatory, as well as our guests today: conductor Chen Bing; and Sosnoff Theater, Fisher Center for the Performing Arts soloists Wang Jianhua on percussion, Wang Lei on sheng, Yu Hongmei on erhu, Zhang Hongyan on pipa, and Zhang Weiwei on suona. Thanks also to folk singer Ji Tian, who has traveled from Shaanxi Sunday, January 26 at 3 pm Province, in Northwest China, to take part in today’s concert. In this program you will learn more about Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 119 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017) The Development of China 's Over - Seven - holes Hulusi Music Hongfei Liu School of Music, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan Hubei, 432000,China Key words: Over seven holes Hulusi, Hulusi music, Li Chunhua. Abstract. In this paper, the advantages and disadvantages of Over seven holes Hulusi and the traditional Hulusi were compared and analyzed. The basic conclusion of the analysis of the results, the present situation and the development potential of the super-seven-hole Hulusi is that the super-seven-hole Hulusi is still in the primary stage of development, and there are contradictions in the process of developing communication with the traditional Hulusi, But the development of Over seven holes Hulusi is the direction of the development of Hulusi, and the traditional Hulusi is also the basis of Over seven holes Hulusi, in the development process of Over seven holes Hulusi to learn from the traditional Hulusi excellent development experience. Over seven holes Hulusi instrument Hulusi music in recent years in the social music has been widely disseminated, showing a hot situation, Hulusi music performance theme is also increasingly rich, but the traditional Hulu instrument because of its sound field performance and other defects, has been in the gourd Silk music development process reflects a larger problem. In order to make Hercules music to sustainable development, in recent years, many people in the Hulusi industry began to improve the traditional gourd instruments. Such as: the 20th century, 70 years Hulusi artist Yu Tianyou according to their own playing experience, and proposed and Hulusi Craftsman Liu Zhen jointly developed a double master tube, four pipe, six pipe gourds, and in the reform of the Hulusi On the basis of the key to the test, which created a 17-degree, six-tube tone gourd silk. -

Sound Power Level Measurement of Sheng, a Chinese Wind Instrument Yue Zhe Zhaoa, Shuo Xian Wua, Jian Zhen Qiua, Li Ling Wub and Hong Huangb

Acoustics 08 Paris Sound power level measurement of Sheng, a Chinese wind instrument Yue Zhe Zhaoa, Shuo Xian Wua, Jian Zhen Qiua, Li Ling Wub and Hong Huangb aState Key Laboratory of Subtropical Building Science, South China University of Technology, 381 Wushan Street, 510640 Guangzhou, China bDept. of Musicology, Xinghai Conservatoire of Music, 510500 Guangzhou, China [email protected] 4331 Acoustics 08 Paris Sheng is one of Chinese traditional wind instruments. But its sound power level has never been carefully measured. In this paper, the sound power measurements of Sheng were performed for the first time in a reverberation chamber according to the ISO standard and Chinese national standard. Two qualified musicians performed on their own instruments in the center of the reverberation chamber. The radiated sound energy and dynamic ranges of the Shengs were investigated by four-channel acoustic measuring equipments. Typical sound power values were obtained through averaging. It was showed that the mean forte sound power level can reach up to 98.0dB with a dynamic range of 22.5dB when music scale was performed. The method discussed here is valuable for the sound power measurements of other musical instruments. The measured sound power data of national musical instruments lay foundations for further investigation into the acoustics of national music halls. installed, inserts to the wind dipper. The lengths of the pipes are different in accordance with the sound pitch. The 1 Introduction player’s fingers are put on the circular apertures located at the underside of the reed pipes. When blowing to the mouthpiece, sound is produced by the resonance of the reed Since the 1960s, studies on the radiated sound pressure or stripes and the column of air in the pipe and come from the sound power levels (SWLs) for the most important string openings on the top of the reed pipes.