An Interview with Liza Lim Madeline Roycroft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composer Performer

Capital Normal University is well-known for its role in educational and cultural transmission and innovation in China. It has set up various departments and offers complete sets of academic disciplines, including liberal arts, science, engineering, management, law, education, art, music and foreign languages etc.. It has also opened many research fields with unique oriental cultural characteristics. Music College of CNU is one of the most famous music schools in China. It comprises 7 departments serving undergraduate and graduate degrees in music education, composing, conducting, piano, vocal, Chinese and western musical instruments, recording technique, dancing,. It also serving doctoral degrees of music education, composing, theory of composing, musicology, music science as well as dancing. The Music College has its chorus troupe, national music band, Chinese and western chamber music band and dancing troupe. Composer Yangqing: Famous composer of Zhou Xueshi: composer,Professor of China. Professor, Dean of Music College Music College of CNU. of CNU. His works involves orchestral <New arrangement: Birds in the Shade>, music, chamber music, dance drama for Chinese Flute, Sheng, Xun, Pipa, Erhu and movie music, His music win a high and Percussion. The musical materials of admiration in china. Leader of this this piece originate from this work—Birds visiting group to USA. Special invited in the Shade for Chinese Flute Solo by to compose a piece of music for both Guanyue Liu. It presents an interesting Chinese and USA instrumentalists. counterpoint in ensemble and shows the technical virtuosity of performers by developing fixed melody patterns and sound patterns. Performer Zhou Shibin: Vice dean, professor Wang Chaohui: Pipa performer . -

2012 02 20 Programme Booklet FIN

COMPOSITION - EXPERIMENT - TRADITION: An experimental tradition. A compositional experiment. A traditional composition. An experimental composition. A traditional experiment. A compositional tradition. Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] 22-23 February 2012, Orpheus Institute, Ghent Belgium The fourth International ORCiM Seminar organised at the Orpheus Institute offers an opportunity for an international group of contributors to explore specific aspects of ORCiM's research focus: Artistic Experimentation in Music. The theme of the conference is: Composition – Experiment – Tradition. This two-day international seminar aims at exploring the complex role of experimentation in the context of compositional practice and the artistic possibilities that its different approaches yield for practitioners and audiences. How these practices inform, or are informed by, historical, cultural, material and geographical contexts will be a recurring theme of this seminar. The seminar is particularly directed at composers and music practitioners working in areas of research linked to artistic experimentation. Organising Committee ORCiM Seminar 2012: William Brooks (U.K.), Kathleen Coessens (Belgium), Stefan Östersjö (Sweden), Juan Parra (Chile/Belgium) Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] The Orpheus Research Centre in Music is based at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium. ORCiM's mission is to produce and promote the highest quality research into music, and in particular into the processes of music- making and our understanding of them. ORCiM -

Instrument List

Instrument List Africa: Europe: Kora, Domu, Begana, Mijwiz 1, Mijwiz 2, Arghul, Celtic & Wire Strung Harps, Mandolins, Zitter, Ewe drum collection, Udu drums, Doun Doun Collection of Recorders, Irish and other whistles, drums, Talking drums, Djembe, Mbira, Log drums, FDouble Flutes, Overtone Flutes, Sideblown Balafon, and many other African instruments. Flutes, Folk Flutes, Chanters and Bagpipes, Bodran, Hang drum, Jews harps, accordions, China: Alphorn and many other European instruments. Erhu, Guzheng, Pipa, Yuequin, Bawu, Di-Zi, Guanzi, Hulusi, Sheng, Suona, Xiao, Bo, Darangu Middle East: Lion Drum, Bianzhong, Temple bells & blocks, Oud, Santoor, Duduk, Maqrunah, Duff, Dumbek, Chinese gongs & cymbals, and various other Darabuka, Riqq, Zarb, Zills and other Middle Chinese instruments. Eastern instruments. India: North America: Sitar, Sarangi, Tambura, Electric Sitar, Small Banjo, Dulcimer, Zither, Washtub Bass, Native Zheng, Yuequin, Bansuris, Pungi Snake Charmer, Flute, Fife, Bottle Blows, Slide Whistle, Powwow Shenai, Indian Whistle, Harmonium, Tablas, Dafli, drum, Buffalo drum, Cherokee drum, Pueblo Damroo, Chimtas, Dhol, Manjeera, Mridangam, drum, Log drum, Washboard, Harmonicas Naal, Pakhawaj, Tamte, Tasha, Tavil, and many and more. other Indian instruments. Latin America: Japan: South American & Veracruz Harps, Guitarron, Taiko Drum collection, Koto, Shakuhachi, Quena, Tarka, Panpipes, Ocarinas, Steel Drums, Hichiriki, Sanshin, Shamisen, Knotweed Flute, Bandoneon, Berimbau, Bombo, Rain Stick, Okedo, Tebyoshi, Tsuzumi and other Japanese and an extensive Latin Percussion collection. instruments. Oceania & Australia: Other Asian Regions: Complete Jave & Bali Gamelan collections, Jobi Baba, Piri, Gopichand, Dan Tranh, Dan Ty Sulings, Ukeleles, Hawaiian Nose Flute, Ipu, Ba,Tangku Drum, Madal, Luo & Thai Gongs, Hawaiian percussion and more. Gedul, and more. www.garritan.com Garritan World Instruments Collection A complete world instruments collection The world instruments library contains hundreds of high-quality instruments from all corners of the globe. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Book Reviews 329 Reference Cited Jones, Stephen. Plucking the Winds

book reviews 329 a general feel for the landscape of Chinese culture. However, if it is intended to be an in- depth discussion on Chinese culture, the work needs more structure. The topics are meant to be woven together through the notion of family, yet the Chinese concept of family (jia) is in fact ambiguous. The meaning of family ranges from the idea of a family unit to broader social relationships, and even to the notion of the state-family (guojia). Without a refined and critical framework, the perspectives in this volume remain loosely connected. reference cited Ong, Walter J. 2002 [1982] Orality and literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge. Pui-lam Law The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Jones, Stephen. Plucking the Winds: Lives of Village Musicians in Old and New China. Chime Studies in East Asian Music Volume 2. Leiden: Chime European Foundation for Chinese Music Research, 2004. x + 426 pages. Maps, illustrations, genealogy, appendices, music examples, bibliography, glossary-index, cd. Paper n. p.; isbn 90-803615-2-6 Stephen Jones is a well known and respected ethmusicologist specializing in the ritual and folk music of Northern China. He is a founding member of the editorial board of the European Foundation for Chinese Music Research, Chime. Since 1989 he has been studying the sheng-guan 笙管 music of the South Gaoluo Music Association. Founded in the Ming Dynasty, Gaoluo is situated between Laishui and Dingxing south of Beijing. The author was assisted by colleagues Xue Yibing and Zhang Zhentao who apparently did “much of the interviewing and notetaking” (viii). -

ANODE 2014 Press Release

ANODE 2014 Festival and Symposium presented by FOCI Arts in partnership with Tulane University and Coup d'Oeil Art Consortium April 10-14, 2014 Press Contact: Ray Evanoff: 504.214.7503 | [email protected] ANODE 2014 ("Artistic New Orleans: Discussions & Extensions") is a brand new contemporary music festival taking place in New Orleans and Chicago in April 10-14, organized by FOCI Arts in partnership with Coup d'oeil Art Consortium and the Tulane University Music Department. It features concerts, public discussions, gallery shows, and educational events showcasing a variety of internationally- prominent contemporary musicians, both based in New Orleans and from across the globe. ANODE 2014 will showcase their work in performances, and explore the visual documentation of their music through a display of scores and sketches at Coup d'oeil Art Consortium's gallery. The festival will feature numerous world premieres and New Orleans first performances, and is the first event of its kind to take place in New Orleans, with a sister concert in Chicago. ANODE 2014 is made possible in part through the generous support of the Harry and Alice Eiler Foundation, inc, the Newcomb College Institute of Tulane University, and Coup d'Oeil Art Consortium. Claus-Steffen Mankopf's attendance is made possible through the generous support of the Goethe- Institut Chicago. The attendance of Kathryn Schulmeister and Joan Arnau Pàmies is made possible through the generous support of New Music USA. 7:30 - Amanda DeBoer Bartlett, Shanna Gutierrez, and Jesse Langen -

Genevieve Lacey Recorder Genevieve Lacey Is a Recorder Virtuoso

Ancient and new! Traversing a thousand years of music for recorder, leading Australian performer Genevieve Lacey weaves together an enticing program of traditional tunes, baroque classics and newly composed music. Genevieve Lacey Recorder Genevieve Lacey is a recorder virtuoso. Her repertoire spans ten centuries, and she collaborates on projects as diverse as her medieval duo with Poul Høxbro, performances with the Black Arm Band, and her role in Barrie Kosky’s production of Liza Lim’s opera ‘The Navigator’. Genevieve has a substantial recording history with ABC Classics, and her newest album, ‘weaver of fictions’, was released in 2008. As a concerto soloist Genevieve has appeared with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Australian Brandenburg Orchestra, Academy of Ancient Music (UK), English Concert (UK), Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra and the Melbourne, West Australian, Tasmanian and Queensland Symphony Orchestras. Genevieve has performed at all the major Australian arts festivals and her European festival appearances have included the Proms, Klangboden Wien, Copenhagen Summer, Sablé, Montalbane, MaerzMusik, Europäisches Musikfest, Mitte Europa, Spitalfields, Cheltenham, Warwick, Lichfield and Huddersfield. Genevieve is strongly committed to contemporary music and collaborations on new works include those with composers Brett Dean, Erkki‐Sven Tuur, Moritz Eggert, Elena Kats‐ Chernin, James Ledger, John Rodgers, Damian Barbeler, Liza Lim, John Surman, Maurizio Pisati, Jason Yarde, Steve Adam, Max de Wardener, Bob Scott and Andrew Ford. As Artistic Director, Genevieve will direct the 2010 and 2012 Four Winds Festivals. In 2009, she will also design a composer mentorship/residency program for APRA‐AMCOS, and program a season of concerts for the 3MBS inaugural Musical Portraits series. -

Download Booklet

SAM HAYDEN FREE DOWNLOAD from our online store Sam Hayden Die Abkehr 11’07 Ensemble Musikfabrik • Stefan Asbury conductor Helen Bledsoe fl ute/piccolo/alto fl ute · Peter Veale oboe/cor anglais Richard Haynes contrabass clarinet · Rike Huy trumpet/piccolo trumpet Bruce Collings trombone · Benjamin Kobler piano · Dirk Rothbrust percussion Hannah Weirich violin · Axel Porath viola · Dirk Wietheger cello Håkon Thelin double bass Enter code: HAYDEN247 nmcrec.co.uk/recording/dieabkehr Die Abkehr (Turning Away) is the most recent drive or melodic elegance of a particular part one composition presented here. As Hayden explains, moment, to the dialogic interplay between different ‘[t]he more poetic meanings of the title hint at a instruments the next and the more complex and critical commentary on the increasingly nostalgic diffuse surface of the totality at another time. What and inward-looking culture of the UK’. Abkehr also remains tantalisingly out of reach is an appreciation means ‘renunciation’, and to what extent that title of the whole and its constituent parts at the same time. is expressed more specifi cally in the piece, over and Again like earlier works, Die Abkehr is highly above being embodied by a musical language that episodic: there are three movements, each seems out of step with what the composer sees as consisting of a number of short individual sections the dominant trends in the UK and that is largely each exploring a particularly type of material. If shared with the rest of his oeuvre is hard to say. As anything, however, Hayden appears to have grown the composer also states, the composition ‘is the bolder in his use of the general pause: time and latest of a cycle of pieces that combine ideas related again, the music recedes into silence, before to “spectral” traditions with algorithmic approaches starting afresh. -

Impact Report 2019 Impact Report

2019 Impact Report 2019 Impact Report 1 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report “ Simone Young and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s outstanding interpretation captured its distinctive structure and imaginative folkloric atmosphere. The sumptuous string sonorities, evocative woodwind calls and polished brass chords highlighted the young Mahler’s distinctive orchestral sound-world.” The Australian, December 2019 Mahler’s Das klagende Lied with (L–R) Brett Weymark, Simone Young, Andrew Collis, Steve Davislim, Eleanor Lyons and Michaela Schuster. (Sydney Opera House, December 2019) Photo: Jay Patel Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report Table of Contents 2019 at a Glance 06 Critical Acclaim 08 Chair’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 2019 Artistic Highlights 14 The Orchestra 18 Farewelling David Robertson 20 Welcome, Simone Young 22 50 Fanfares 24 Sydney Symphony Orchestra Fellowship 28 Building Audiences for Orchestral Music 30 Serving Our State 34 Acknowledging Your Support 38 Business Performance 40 2019 Annual Fund Donors 42 Sponsor Salute 46 Sydney Symphony Under the Stars. (Parramatta Park, January 2019) Photo: Victor Frankowski 4 5 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report 2019 at a Glance 146 Schools participated in Sydney Symphony Orchestra education programs 33,000 Students and Teachers 19,700 engaged in Sydney Symphony Students 234 Orchestra education programs attended Sydney Symphony $19.5 performances Orchestra concerts 64% in Australia of revenue Million self-generated in box office revenue 3,100 Hours of livestream concerts -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

1 © Luisa Greenfield

1 © Luisa Greenfield © Luisa MING TSAO (*1966) 1 – 7 ensemble ascolta Conductors: 1 – 7 Johannes Kalitzke, Andrea Nagy, clarinet 8 – 19 Stefan Schreiber Erik Borgir, violoncello Recording dates: 1 – 7 18–19 Jul 2014, Hubert Steiner, guitar 8 – 19 28–29 Nov 2015 Plus Minus (2012 /13) Mirandas Atemwende (2014 /15) Andrew Digby, trombone Recording venues: 1 – 7 KvB-Saal Funkhaus Köln, Germany Realization of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Markus Schwind, trumpet 8 – 19 Teldex Studio Berlin, Germany “Plus Minus” Anne-Maria Hoelscher, accordion Producer: 1 – 7 Eckhard Glauche Florian Hoelscher, piano 8 – 19 Markus Heiland 1 Plus Minus – Page I. 05:53 8 Erwartung 02:54 Martin Homann, percussion Recording engineer: 1 – 7 Mark Hohn Boris Müller, percussion 8 – 19 Markus Heiland Julian Belli, percussion Technique / Editing: 1 – 7 Astrid Groflmann 2 Plus Minus – Page II. 05:38 9 Es gibt einen Ort 02:33 Akos Nagy, percussion Executive Producer: 1 – 7 Harry Vogt 8 – 19 Markus Heiland 3 Plus Minus – Page III. 04:15 10 Du entscheidest dich 02:01 8 – 19 Kammerensemble Final mastering: Markus Heiland Neue Musik Berlin Graphic Design: Alexander Kremmers 4 Plus Minus – Page IV. 03:24 11 Heute 04:44 Miranda: Tajana Raj, soprano (paladino media), cover based on Caliban: Christoph Gareisen and artwork by Erwin Bohatsch 5 Plus Minus – Page V. 03:04 12 Helligkeitshunger 04:36 Jan Pohl, speaking voices Publisher: Edition Peters Rebecca Lenton, flute Gudrun Reschke, oboe / english horn 1 – 7 © 2014 Produced by 6 13 Plus Minus – Page VI. 03:59 Das Geschriebene 03:44 Theo Nabicht, bass clarinet Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln. -

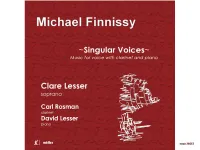

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices 1 Lord Melbourne †* 15:40 2 Song 1 5:29 3 Song 16 4:57 4 Song 11 * 3:02 5 Song 14 3:11 6 Same as We 7:42 7 Song 15 7:15 Beuk o’ Newcassel Sangs †* 8 I. Up the Raw, maw bonny 2:21 9 II. I thought to marry a parson 1:39 10 III. Buy broom buzzems 3:18 11 IV. A’ the neet ower an’ ower 1:55 12 V. As me an’ me marra was gannin’ ta wark 1:54 13 VI. There’s Quayside fer sailors 1:19 14 VII. It’s O but aw ken weel 3:17 Total Duration including pauses 63:05 Clare Lesser soprano David Lesser piano † Carl Rosman clarinet * Michael Finnissy – A Singular Voice by David Lesser The works recorded here present an overview of Michael Finnissy’s continuing engagement with the expressive and lyrical possibilities of the solo soprano voice over a period of more than 20 years. It also explores the different ways that the composer has sought to ‘open-up’ the multiple tradition/s of both solo unaccompanied song, with its universal connotations of different folk and spiritual practices, and the ‘classical’ duo of voice and piano by introducing the clarinet, supremely Romantic in its lyrical shadowing of, and counterpoints to, the voice in Song 11 (1969-71) and Lord Melbourne (1980), and in an altogether more abrasive, even aggressive, way in the microtonal keenings and rantings of the rarely used and notoriously awkward C clarinet in Beuk O’ Newcassel Sangs (1988).