The Third Sector in Falkirk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Registration Reference PM3/674 Falkirk Wheel

First Registration Reference PM3/674 Falkirk Wheel - Tamfourhill - Falkirk - Carronshore - Stenhousemuir - FVRH 6 Camelon - Falkirk - Bainsford - Carronshore - Kinnaird Park - FVRH 6A Monday to Saturday Ref.No.: 01LW Service No 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A 6 6A Falkirk Wheel, Visitor Centre .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 0928 .... 1028 .... 1128 .... 1228 .... 1328 .... 1428 .... 1528 .... Tamfourhill, Lime Road 0555 .... .... .... 0730 .... 0830 .... 0930 .... 1030 .... 1130 .... 1230 .... 1330 .... 1430 .... 1530 .... Camelon, Ochiltree Terrace .... .... .... 0654 .... 0759 .... 0859 .... 0959 .... 1059 .... 1159 .... 1259 .... 1359 .... 1459 .... 1559 Summerford, Windsor Road 0600 .... .... 0700 0735 0805 0835 0905 0935 1005 1035 1105 1135 1205 1235 1305 1335 1405 1435 1505 1535 1605 Falkirk Community Hospital 0607 .... .... 0707 0742 0812 0842 0912 0942 1012 1042 1112 1142 1212 1242 1312 1342 1412 1442 1512 1542 1612 Falkirk, ASDA arr0610 .... .... 0710 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 1445 1515 1545 1615 Falkirk, ASDA dep .... 0611 0641 0711 0750 0820 0850 0920 0950 1020 1050 1120 1150 1220 1250 1320 1350 1420 1450 1520 1550 1620 Carron Centre .... 0619 0649 0719 0758 0828 0858 0928 0958 1028 1058 1128 1158 1228 1258 1328 1358 1428 1458 1528 1558 1628 Carronshore, The Shore .... 0625 0655 0725 0804 0834 0904 0934 1004 1034 1104 1134 1204 1234 1304 1334 1404 1434 1504 1534 1604 1634 Stenhousemuir, ASDA .... 0633 0703 0733 0812 0842 0912 0942 1012 1042 1112 1142 1212 1242 1312 1342 1412 1442 1512 1542 1612 1642 Larbert, Glenbervie Drive .... .... 0709 .... 0818 .... 0918 .... 1018 .... 1118 .... 1218 .... 1318 ... -

Tamfourhill: Temporary Camp

TAMFOURHILL: TEMPORARY CAMP Between Falkirk town centre and the Falkirk Wheel, to the south of Watling Lodge, in an open field between the Union Canal and Tamfourhill Wood, is the site of a Roman temporary camp. The camp is sometimes visible in aerial photographs, but cannot be seen on the ground today. To the north, along Tamfourhill Road is the best-preserved section of Antonine Wall Ditch and the site of a Roman fortlet on the grounds of Watling Lodge. HISTORY OF DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION: The Tamfourhill camp was first identified as This new extension bypasses the camp on its cropmarks in aerial photographs in 1977. In north side, and archaeological investigations 2000, the Falkirk Millennium Link Project built a were carried out prior to construction, but no new extension on the Union Canal to join it with excavations took place within the area of the Forth and Clyde Canal at the Falkirk Wheel. the camp. DESCRIPTION AND INTERPRETATION: Examination of aerial photographs and been recorded in front of entrance gaps investigation on the ground have revealed on the camp’s north, east, and south sides. that the Tamfourhill camp lies about 300m The camp appears to face the nearby fortlet, south of the Antonine Wall and about 400m and has been interpreted as a probable south-west of the fortlet at Watling Lodge. construction camp used during the building The camp is oriented on a slight north-east to of the Antonine frontier. south-west axis and encloses an area of about 2.7ha (6.7 acres). Tituli (staggered sections of bank and ditch that offered extra protection to the entryways or gates of Roman camps) have BIBLIOGRAPHY: CANMORE Record: http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/ site/46750/ Goodburn, R. -

16/01/2017 F25 Falkirk

F25 Monday to Friday Valid from: 16/01/2017 F25 FALKIRK - STANDBURN Via Circular Polmont Maddiston Shieldhill Service No.: F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 Notes: Falkirk (Bus Station) 0902 1102 1302 1502 1702 1902 Falkirk (Corentin Court) arr 0908 1108 1308 1508 1708 1908 Falkirk (Corentin Court) dep 0910 1110 1310 1510 1710 1910 Falkirk (Bus Station) 0916 1116 1316 1516 1716 1916 Laurieston (Mary Square) 0921 1121 1321 1521 1721 1921 Polmont (Black Bull) 0925 1125 1325 1525 1725 1925 Polmont (St Margarets Health Centre) 0931 1131 1331 1531 1731 1931 Redding Tesco arr 0936 1136 1336 1536 1736 1936 Redding Tesco dep 0938 1138 1338 1538 1738 1938 Wallacestone Brae 0944 1144 1344 1544 1744 1944 Maddiston, Primary School 0952 1152 1352 1552 1752 1952 Standburn 0955 1155 1355 1555 1755 1955 F25 Standburn - Falkirk Via Shieldhill F25 Standburn - Falkirk Via Shieldhill & Glen Village Service No.: F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 Notes: Standburn 0800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 1957 Avonbridge, Church 0805 1005 1205 1405 1605 1805 2002 California, Primary School 0810 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2007 Shieldhill (Clachan) 0812 1012 1212 1412 1612 1812 2009 Shieldhill (Cross) 0814 1014 1214 1414 1614 1814 2010 Glen Village ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- 2016 Falkirk (ASDA) ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- 2023 Shieldhill Easton Drive eastbound 0816 1016 1216 1416 1616 1816 ---- Wallacestone Brae 0821 1021 1221 1421 1621 1821 ---- Brightons (Cross) 0825 1025 1225 1425 1625 1825 ---- Prison Service College 0827 1027 1227 1427 1627 1827 ---- Redding, Tesco arr 0830 1030 -

FORTH, CLYDE and UNION CANALS Notes on Multi-Use Access

FORTH, CLYDE AND UNION CANALS Notes on multi-use access The Forth and Clyde Canal stretches 35 miles between Bowling, on the Clyde west of Glasgow, and the Forth estuary east of Falkirk, linking directly via the Union Canal to Edinburgh. Walkers and cyclists may now be a more common sight than the horses for whom the towpaths were originally created, and riding a horse alongside the canal may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act, horse-riders enjoy equal access rights to other non-motorised access takers. Most of the former barriers along the towpath have been removed or modified to allow multi-use access, although there are a few places where the passable width is very narrow, or where steps have been installed to divert around obstructions in the line of the towpath may not be passable with a horse. These notes have been produced by British Horse Society Scotland to help identify location and brief details of features which may influence multi-use of the Forth and Clyde and Union Canals. The notes are intended to supplement information already available from other sources, including detailed route guides, http://www.scottishcanals.co.uk/our-canals/forth-- clyde-canal and other relevant websites. The background information for these notes was provided by volunteers who surveyed the route in 2014 as part of a multi-use long distance route audit funded by Scottish Natural Heritage. BHS will endeavour to update notes as and when notification of subsequent changes is received, but cannot guarantee accessibility or the accuracy of information provided. -

The Falkirk Wheel Is the World’S Only Rotating Boat Lift, Combining Ancient Principles with 21St Century Engineering

The Falkirk Wheel is the world’s only rotating boat lift, combining ancient principles with 21st century engineering. The Falkirk Wheel is easily accessible in the heart of Scotland. Stirling The Falkirk Wheel 23 MILES Edinburgh 23 Miles Glasgow • Activities • Adventure & Water play parks • Boat Tours • Café with locally sourced produce • Car, Coach & Campervan Parking • Coach drop off & parking • Electric bike hire - Great for cycling to the Kelpies along the tow path • Holiday hire boat base • Meeting & Conference facilities • Retail • Wood fred pizza oven Our Tours - Fully Accessible Revolution Tour - Scheduled Daily Capacity 96, Duration: 35 minutes Embark the boat from directly outside the visitor centre to sail 35m into the sky during a 180 degree rotation to the top of The Wheel. Our crew will share knowledge and information about the history and workings of this iconic structure. You will then pause briefy at the top to take in views across central Scotland before beginning the descent back to the visitor centre. This is our shortest tour. Ideal for: tight travel trade itineraries; families with young children. Original Tour - Scheduled Daily Capacity 96, Duration: 60 minutes After sailing through the sky to to top of The Wheel, you will exit this feat of engineering and sail along the aqueduct. This tour takes you through the Roughcastle tunnel to the opening of the Union Canal and back again, rotating down through The Wheel. You will learn about The Wheel itself and the rich Roman history which surrounds the area. Blueprint Tour - Exclusive for TT partners & groups Capacity 20 – 55, Duration: 80 minutes The Blueprint Tour offers an immersive experience, adding the wow factor. -

First Falkirk Wheel

First Falkirk Wheel - Tamfourhill - Falkirk - Bainsford - Carronshore - Stenhousemuir - FVRH 6 Camelon - Falkirk - Bainsford - Antonshill - Stenhousemuir - FVRH 7 Camelon - Falkirk - Bainsford - Kinnaird Park - FVRH - Bonnybridge - Denny - Fankerton 8 Monday 5 April Ref.No.: 02L3 Service No 868868676867 6 8 6 7 7 6 8 6 Falkirk Wheel, Visitor Centre .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 0916 .... 46 .... 16 .... .... 1646 .... 1716 Tamfourhill, Lime Road .... 0541 .... .... 0735 .... 0819 .... 0849 .... 0919 .... 49 .... 19 .... .... 1649 .... 1719 Camelon, Ochiltree Terrace .... .... .... 0703 .... 0801 .... 0831 .... 0901 .... 0931 .... 01 .... 31 1631 .... 1701 .... Summerford, Windsor Road .... 0545 .... 0709 0739 0809 0824 0839 0854 0909 0924 0939 54 09 24 39 1639 1654 1709 1724 Falkirk Community Hospital .... 0551 .... 0715 0745 0816 0831 0846 0901 0916 0931 0946 01 16 31 46 1646 1701 1716 1731 Falkirk, ASDA arr .... 0554 .... 0718 0748 0819 0834 0849 0904 0919 0934 0949 04 19 34 49 1649 1704 1719 1734 Falkirk, ASDA dep .... 0557 .... 0721 0751 0822 0837 0852 0907 0922 0937 0952 07 22 37 52 1652 1707 1722 1737 Carron Centre .... 0603 .... 0727 0757 0830 0845 0900 0915 0930 0945 1000 then 15 30 45 00 1700 1715 1730 1745 Stenhousemuir, Carron Dams .... .... .... 0732 .... 0835 .... .... .... 0935 .... .... at .... 35 .... .... .... .... 1735 .... Carronshore, The Shore .... 0608 .... .... 0802 .... 0851 .... 0921 .... 0951 .... these 21 .... 51 .... .... 1721 .... 1751 Antonshill, Falkland Place .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 0909 .... .... .... 1009 mins. .... .... .... 09 until 1709 .... .... .... Stenhousemuir, ASDA .... 0615 .... 0736 0809 0839 0859 0914 0929 0939 0959 1014 past 29 39 59 14 1714 1729 1739 1759 Larbert, Main Street .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 0920 .... .... .... 1020 each .... .... .... 20 1720 .... .... .... Larbert, Glenbervie Drive .... 0620 .... .... 0814 .... 0906 .... 0936 .... 1006 .... hour 36 .... 06 .... .... 1736 .... 1806 Larbert, Muirhall Road .... .... .... 0743 .... 0846 ... -

Some Excavations on the Line of the Antonine Wall, 1994–2001

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 132 (2002), 259–304 Some excavations on the line of the Antonine Wall, 1994–2001 Prepared for publication by Andrew Dunwell*, Geoff Bailey†, Alan Leslie‡ & Andrea Smith** from reports and contributions by J Atkinson, G Bailey, K Cameron, A Duffy, C Ellis, J Evans, B Glendinning, J Gooder, M Hastie, A Leslie, R McCullagh, E Photos-Jones, P Robins, K Speller & R Strachan ABSTRACT The results of over 30 separate excavations and watching briefs along the line of the Antonine Wall are presented. The alignment and character of the frontier works and fort defences were clarified in several places. New information was obtained regarding a possible enclosure on the north side of the Wall near Auchendavy. INTRODUCTION Roman Temporary Camp (Lowe & Moloney 2000), Falkirk Roman fort (Bailey, forthcom- This report pulls together the results of over ing a), Kinneil (Glendinning 2000), and Mum- 30 excavations and watching briefs conducted rills annexe (Bailey, forthcoming b). A ford along the line of the Antonine Wall between discovered near Rough Castle, which was 1994 and 2001. Preliminary accounts of the originally thought to have been Roman, as it results of these investigations have been pub- lay beside the Military Way, was subsequently lished in the relevant issues of Discovery and proved to have been prehistoric (Discovery Excavation in Scotland and Britannia. Excav Scot 1995,12&1996, 42; Hamilton et Summary mention is made of some of the al 2001). interventions recorded here in the recently The format of this report follows those of revised fifth edition of The Antonine Wall: A previous compilations (most recently Keppie Handbook to the Surviving Remains (Robert- et al 1995) in many respects. -

Braes Area Path Network

Discover the paths in and around The Braesarea of Falkirk Includes easy to use map and eleven suggested locations something for everyone Discover the paths in and around The Braes area of Falkirk A brief history Falkir Path networks key and page 1 Westquarter Glen 5 The John circular Muir Way 2 Polmont Wood 8 NCN 754 Walkabout Union Canal 3 Brightons Wander 10 4 Maddiston to Rumford Loop 12 Shieldhill 5 Standburn Meander 14 6 Whitecross to 16 Muiravonside Loop 7 Big Limerigg Loop 18 8 Wallacestone Wander 20 Califor B803 9 Avonbridge Walk 22 10 Shieldhill to California 24 B810 and back again B 11 Slamannan Walkabout 26 River Avon r Slamannan e w o T k c B8022 o l C Binniehill n a n B825 n B8021 a m a l Limerigg S This leaflet covers walks in and around the villages of Westquarter, Polmont, Brightons, Maddiston, Standburn, Wallacestone, Whitecross, Limerigg, Avonbridge, Slamannan and Shieldhill to California. The villages are mainly of mining origin providing employment for local people especially during the 18th-19th centuries when demand for coal was at its highest. Today none of the pits are in use but evidence of the industrial past can still be seen. 2 rk Icon Key John Muir Way National Cycle M9 Network (NCN) Redding River Avon Polmont A801 Brightons Whitecross Linlithgow Wallacestone Maddiston nia B825 Union Canal Standburn 8028 B825 River Avon Avonbridge A801 Small scale coal mining has existed in Scotland since the 12th Century. Between the 17th & 19th Century the demand for coal increased greatly. -

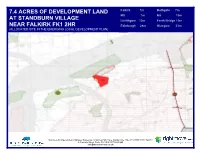

Residential Development Plots at Duncrub, Dunning

7.4 ACRES OF DEVELOPMENT LAND Falkirk 7m Bathgate 7m M9 7m M8 10m AT STANDBURN VILLAGE Linlithgow 13m Forth Bridge 15m NEAR FALKIRK FK1 2HR Edinburgh 28m Glasgow 33m (ALLOCATED SITE IN THE EMERGING LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN) Photo: The steading from the North West www.mccraemccrae.co.uk McCrae & McCrae Limited, Chartered Surveyors, 12 Abbey Park Place, Dunfermline, Fife, KY12 7PD 01383 722454 9 Charlotte Street, Perth, PH1 5LW 01738 634669 [email protected] McCrae & McCrae Limited, Chartered Surveyors, 12 Abbey Park Place, Dunfermline, Fife, KY12 7PD 01383 722454 9 Charlotte Street, Perth, PH1 5LW 01738 634669 [email protected] OFFERS OVER £375,000 ] DESCRIPTION This 7.4 acre (approx) development site is located at the south west end of the village of Standburn, near Maddiston to the south of Falkirk with entry from the main street. This site has been allocated in the emerging Falkirk Local Development Plan for residential dwellings and possible care-home facility (site H73) – the exact date of allocation is to be confirmed. Discussions have been held with Falkirk Council and in principal they are supportive of a 90 bed care facility in addition to the residential dwellings. Whilst the number of residential dwellings has been estimated, Falkirk Council are amenable to an increase of circa. 45 units, subject to planning (see attached alternative design proposals on final two pages) SITUATION Standburn is located on the B825 and is reached via the Bowhouse Roundabout on the A801 which is the link road between the M9 and M8. The village is within easy reach of the M9 for Stirling, Glasgow, Edinburgh and the Forth Road Bridge. -

2 Rowan Crescent, Tamfourhill, Falkirk, Fk1 4Rq

2 ROWAN CRESCENT, TAMFOURHILL, FALKIRK, FK1 4RQ FIXED PRICE £57,000 ENERGY PERFORMANCE RATING: 'D' GENERAL DESCRIPTION: This beautifully presented one bedroom VILLA will appeal both to the 1st time buyer or investor looking for an easily maintained home. The ground floor comprises lounge with feature staircase, well fitted kitchen with washing machine, cooker and fridge/freezer included in the sale price. Upstairs there is a double bedroom with built-in wardrobe and a tiled bathroom with corner bath/shower, w.c and wash hand basin. The property is enhanced by gas fired central heating and double glazing. To front is an open area of garden ground with a driveway and detached garage to side. To the rear there is an enclosed shared drying green. Tamfourhill is a popular residential location well served by local amenities catering for most daily needs and only a few miles from Falkirk town centre with its wide and diverse range of shopping, leisure and recreational facilities. There are also a number of bars and restaurants within the town and surrounding area along with country parks and canal walks for the more energetic. For the commuter there is good access by either public or private transport to many areas of commerce within the central belt and schooling for all ages is to hand. TRAVEL: From Falkirk town centre take the Camelon Road (A803) taking the 1st exit at the Beefeater roundabout onto Glenfuir Road (B816). Continue along this road straight over the 1st roundabout and take the 2nd turning on your right into Tamfourhill Road (B816). -

Westquarter Dovecote Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC166 Designations: Listed Building (LB8315) Taken into State care: 1950 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE WESTQUARTER DOVECOT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE WESTQUARTER DOVECOT CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 4 2.3 Historical values 5 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 8 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 8 2.6 Natural heritage values 9 2.7 Contemporary/use values 9 3 Major gaps in understanding 9 4 Associated properties 10 5 Keywords 10 Bibliography 10 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 12 Appendix 2: General History of Doocots 13 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. -

Information February 2008

Insight 2006 Population estimates for settlements and wards Information February 2008 This Insight contains the latest estimates of the population of settlements and wards within Falkirk Council area. These update the 2005 figures published in April 2007. The total population of the Council area is 149,680. Introduction Table 2: Settlement population estimates 2006 Settlement Population This Insight contains the latest (2006) estimates of Airth 1,763 the total population of each of the settlements and Allandale 271 wards in Falkirk Council area by the R & I Unit of Avonbridge 606 Corporate & Commercial Services. The ward Banknock 2,444 estimates are for the multi-member wards which Blackness 129 came into effect at the elections in May 2007. Bo'ness 14,568 Bonnybridge 4,893 Brightons 4,500 The General Register Office for Scotland now California 693 publish small area population estimates for the 197 Carron 2,526 datazones in the Council area and these have been Carronshore 2,970 used to estimate the population of the wards and Denny 8,084 also of the larger settlements. The estimates for the Dennyloanhead 1,240 smaller settlements continue to be made by rolling Dunipace 2,598 forward the figures from the 2001 Census, taking Dunmore 67 account of new housing developments and Falkirk 33,893 controlling the total to the 2006 Falkirk Council mid Fankerton 204 Grangemouth 17,153 year estimate of population. Greenhill 1,824 Haggs 366 2006 Population estimates Hall Glen & Glen Village 3,323 Head of Muir 1,815 Table 1 shows the 2006 population