Westquarter Dovecote Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16/01/2017 F25 Falkirk

F25 Monday to Friday Valid from: 16/01/2017 F25 FALKIRK - STANDBURN Via Circular Polmont Maddiston Shieldhill Service No.: F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 Notes: Falkirk (Bus Station) 0902 1102 1302 1502 1702 1902 Falkirk (Corentin Court) arr 0908 1108 1308 1508 1708 1908 Falkirk (Corentin Court) dep 0910 1110 1310 1510 1710 1910 Falkirk (Bus Station) 0916 1116 1316 1516 1716 1916 Laurieston (Mary Square) 0921 1121 1321 1521 1721 1921 Polmont (Black Bull) 0925 1125 1325 1525 1725 1925 Polmont (St Margarets Health Centre) 0931 1131 1331 1531 1731 1931 Redding Tesco arr 0936 1136 1336 1536 1736 1936 Redding Tesco dep 0938 1138 1338 1538 1738 1938 Wallacestone Brae 0944 1144 1344 1544 1744 1944 Maddiston, Primary School 0952 1152 1352 1552 1752 1952 Standburn 0955 1155 1355 1555 1755 1955 F25 Standburn - Falkirk Via Shieldhill F25 Standburn - Falkirk Via Shieldhill & Glen Village Service No.: F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 F25 Notes: Standburn 0800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 1957 Avonbridge, Church 0805 1005 1205 1405 1605 1805 2002 California, Primary School 0810 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2007 Shieldhill (Clachan) 0812 1012 1212 1412 1612 1812 2009 Shieldhill (Cross) 0814 1014 1214 1414 1614 1814 2010 Glen Village ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- 2016 Falkirk (ASDA) ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- 2023 Shieldhill Easton Drive eastbound 0816 1016 1216 1416 1616 1816 ---- Wallacestone Brae 0821 1021 1221 1421 1621 1821 ---- Brightons (Cross) 0825 1025 1225 1425 1625 1825 ---- Prison Service College 0827 1027 1227 1427 1627 1827 ---- Redding, Tesco arr 0830 1030 -

Braes Area Path Network

Discover the paths in and around The Braesarea of Falkirk Includes easy to use map and eleven suggested locations something for everyone Discover the paths in and around The Braes area of Falkirk A brief history Falkir Path networks key and page 1 Westquarter Glen 5 The John circular Muir Way 2 Polmont Wood 8 NCN 754 Walkabout Union Canal 3 Brightons Wander 10 4 Maddiston to Rumford Loop 12 Shieldhill 5 Standburn Meander 14 6 Whitecross to 16 Muiravonside Loop 7 Big Limerigg Loop 18 8 Wallacestone Wander 20 Califor B803 9 Avonbridge Walk 22 10 Shieldhill to California 24 B810 and back again B 11 Slamannan Walkabout 26 River Avon r Slamannan e w o T k c B8022 o l C Binniehill n a n B825 n B8021 a m a l Limerigg S This leaflet covers walks in and around the villages of Westquarter, Polmont, Brightons, Maddiston, Standburn, Wallacestone, Whitecross, Limerigg, Avonbridge, Slamannan and Shieldhill to California. The villages are mainly of mining origin providing employment for local people especially during the 18th-19th centuries when demand for coal was at its highest. Today none of the pits are in use but evidence of the industrial past can still be seen. 2 rk Icon Key John Muir Way National Cycle M9 Network (NCN) Redding River Avon Polmont A801 Brightons Whitecross Linlithgow Wallacestone Maddiston nia B825 Union Canal Standburn 8028 B825 River Avon Avonbridge A801 Small scale coal mining has existed in Scotland since the 12th Century. Between the 17th & 19th Century the demand for coal increased greatly. -

Residential Development Plots at Duncrub, Dunning

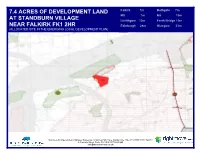

7.4 ACRES OF DEVELOPMENT LAND Falkirk 7m Bathgate 7m M9 7m M8 10m AT STANDBURN VILLAGE Linlithgow 13m Forth Bridge 15m NEAR FALKIRK FK1 2HR Edinburgh 28m Glasgow 33m (ALLOCATED SITE IN THE EMERGING LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN) Photo: The steading from the North West www.mccraemccrae.co.uk McCrae & McCrae Limited, Chartered Surveyors, 12 Abbey Park Place, Dunfermline, Fife, KY12 7PD 01383 722454 9 Charlotte Street, Perth, PH1 5LW 01738 634669 [email protected] McCrae & McCrae Limited, Chartered Surveyors, 12 Abbey Park Place, Dunfermline, Fife, KY12 7PD 01383 722454 9 Charlotte Street, Perth, PH1 5LW 01738 634669 [email protected] OFFERS OVER £375,000 ] DESCRIPTION This 7.4 acre (approx) development site is located at the south west end of the village of Standburn, near Maddiston to the south of Falkirk with entry from the main street. This site has been allocated in the emerging Falkirk Local Development Plan for residential dwellings and possible care-home facility (site H73) – the exact date of allocation is to be confirmed. Discussions have been held with Falkirk Council and in principal they are supportive of a 90 bed care facility in addition to the residential dwellings. Whilst the number of residential dwellings has been estimated, Falkirk Council are amenable to an increase of circa. 45 units, subject to planning (see attached alternative design proposals on final two pages) SITUATION Standburn is located on the B825 and is reached via the Bowhouse Roundabout on the A801 which is the link road between the M9 and M8. The village is within easy reach of the M9 for Stirling, Glasgow, Edinburgh and the Forth Road Bridge. -

Information February 2008

Insight 2006 Population estimates for settlements and wards Information February 2008 This Insight contains the latest estimates of the population of settlements and wards within Falkirk Council area. These update the 2005 figures published in April 2007. The total population of the Council area is 149,680. Introduction Table 2: Settlement population estimates 2006 Settlement Population This Insight contains the latest (2006) estimates of Airth 1,763 the total population of each of the settlements and Allandale 271 wards in Falkirk Council area by the R & I Unit of Avonbridge 606 Corporate & Commercial Services. The ward Banknock 2,444 estimates are for the multi-member wards which Blackness 129 came into effect at the elections in May 2007. Bo'ness 14,568 Bonnybridge 4,893 Brightons 4,500 The General Register Office for Scotland now California 693 publish small area population estimates for the 197 Carron 2,526 datazones in the Council area and these have been Carronshore 2,970 used to estimate the population of the wards and Denny 8,084 also of the larger settlements. The estimates for the Dennyloanhead 1,240 smaller settlements continue to be made by rolling Dunipace 2,598 forward the figures from the 2001 Census, taking Dunmore 67 account of new housing developments and Falkirk 33,893 controlling the total to the 2006 Falkirk Council mid Fankerton 204 Grangemouth 17,153 year estimate of population. Greenhill 1,824 Haggs 366 2006 Population estimates Hall Glen & Glen Village 3,323 Head of Muir 1,815 Table 1 shows the 2006 population -

Westquarter & Redding Cricket Club

On the Road to Becoming a Community Club Stephen Sutton, Director Westquarter & Redding Cricket Club C.I.C. Club formed as a Financial Crash Cricket and Bicycle First game played at means interest rates Club Bailliefields 6th June plummet 1908 1999 2010 1995 2004 Sold ground moved Substantial repairs to Roughhaugh Farm required to with over 8 acres of Farmhouse land Brief History First Step – Secure the club financially Ideas • What is right for us? • What assets do we have? • Suggestion of turning farmhouse into Children’s Nursery Validate & Research • Spoke with connections who work in childcare • Commercial rent gives much better ROI • Researched nurseries and demand in the area Action & Follow Up • Sent out detailed proposal to nursery companies • Met with those who responded Making Decisions Do What We Have Been Doing • Easy option • Club eventually runs out of money OR Take A Calculated Risk • Demand is there, still a risk • Secure the club financially Getting Things Done Hard Work Pays Off! Where do we want to be? • Thriving junior section • Age level games (Under 12, 14) • Second XI • Improved facilities • More volunteers to help build and grow the club • Integrated into the community • Ex players involved with the club • Secure Financial future Every Journey Starts with a Single Step How Do we Build the Junior Section? • Make it Fun • Make it Safe • Promote it • Engage whole family • Welcoming to All • NOT a baby sitting service! Welcome to the Westies • Qualified Coaches • Started winter session • Coach into local schools • -

Planning Applications Received 19 July 2020

PLANNING AND TRANSPORTATION WEEKLY PLANNING BULLETIN List of Valid Applications Submitted Date: 22 July 2020 Applications contained in this List were submitted during the week ending 19 July 2020. The Weekly List Format This List is formatted to show as much information as possible about submitted applications. Below is a description of the information included in the List: this means... Application : a unique sequential reference number for the application. Number Application : the type of application, e.g. detailed planning application, Listed Building Type Consent, Advertisement Consent. Proposal : a description of what the applicant sought consent for. Location : the address where they proposed to do it Community : the Community Council Area in which the application site lies Council Ward : the number and Name of the Council Ward in which the application site lies Applicants : the name of the individual(s) or organisation who applied for the consent Name and and their mailing address Address Case Officer : the name, telephone number and e-mail address of the officer assigned to the case. Grid Reference : the National Grid co-ordinates of the centre of the application site. Application No : P/20/0148/FUL Earliest Date of 10 August 2020 Decision Application Type : Planning Permission Hierarchy Level Local Proposal : Erection of Outbuilding and Formation of Vehicular access Location : Flat A Craig Logie Westquarter Avenue Westquarter Falkirk FK2 9SP Community Council : Lower Braes Ward : 08 - Lower Braes Applicant : Mrs Susan Kennedy -

1 Avonbridge & Standburn Community Council Minutes of the Monthly

Avonbridge & Standburn Community Council Minutes of the Monthly Meeting - Thursday 10thMay 2018 at 7.15pm Drumbowie School Standburn 1. Present G. Addison, N Cochrane, A. Frerichs, E. Chappell, J. Hirst, H. Kidd, D. Goldie, Cllr J Kerr, Cllr G Hughes, Cllr McLuckie and eight members of the public. Apologies D. Cameron, I. McGillivray, J Hunter, C. Sharples, D. Park, PC Todd, S & G Robertson. 2. Police Report – Emailed report PC not present at the meeting, no significant events this month. Since the last report (12/04/2018) there have been 7 calls made to police relating to the village of Avonbridge. Those consist of the following call types: Domestic Incident Road Traffic Matter (false call, good intent) Abandoned/Silent 999 Road Traffic Collision House Fire External Agency requesting welfare check Public Assistance re possible scam/bogus workman 2 crimes have been recorded in Avonbridge since the date of the last report in relation to Assault (non-injury), Vandalism (broken pane of glass in front door) and Threatening & Abusive Behaviour (Domestic) Obstruction of and disturbance of a Badger Sett For the village of Standburn there has been one call made to police in relation to Public Nuisance (unidentified male alleged to be trying to damage temp. crossing) There are no recorded crimes in that time within Standburn. 3. Community Safety Team Report Presented by GA. 4. Approval of Minutes from meeting held on Thursday 12th April 2018 Proposed by E. Chappell Seconded by H Kidd 5. Matters Arising from Minutes of Previous Meeting Xmas lights – GA has form and will complete for funding Muiravonside Country Park update - parking charges – letter sent registering our objection, joint meeting held with reps from ASCC, Maddiston CC, SCCC and Brightons CC with Claire Mennin of Falkirk Community Trust. -

26 Langton Road, Westquarter, Falkirk, Fk2 9Sz

26 LANGTON ROAD, WESTQUARTER, FALKIRK, FK2 9SZ OFFERS OVER £90,000 ENERGY PERFORMANCE RATING: 'D' GENERAL DESCRIPTION: This superb three bedroom Semi-detached Villa enjoys an outstanding location within a popular residential setting. Open aspects to the front and wooded aspects to the rear are only a minor part of its unique appeal. Well maintained and in good order the accommodation comprises:- welcoming reception hall, large lounge/diningroom with focal fireplace, re-fitted dining kitchen and re-fitted bathroom on the ground floor. Upstairs there are three generous bedrooms (possibility of en-suite to bedroom 1 subject to planning) and access to a useful loft space. Double glazing and gas central heating have been installed. To the front, side and rear are mature established garden grounds with ample space for a garage/hard stand and off-street parking suitable for boat/caravan if required. The garden shed is also to be included within the purchase price. Westquarter is a popular location well served by local amenities catering for most daily needs. Supermarkets at Redding, Polmont and Falkirk which also has a pedestrianised High Street and Retail Park, they are only a short distance by either public or private transport. For those wishing to commute there are good services by road or rail to most areas of commerce within Central Scotland. Schooling for all ages is to hand along with good sporting, leisure and recreational facilities. TRAVEL: From Falkirk take the B803 Callendar Road, pass Callendar Park follow the road and pass through Lauriston. Take the turning on the right sign posted Westquarter into Westquarter Avenue and then first right into Carhowden Road at the end of the road bear left into Langton Road, continue past the first turn-off on your right and number 26 is on your right hand side. -

Tour of Falkirk & the Kelpies

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Tour of Falkirk & The Kelpies ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 11.5 miles/18 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 4 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long but fairly flat 3 The Kelpies GRANGEMOUTH Rosebank Distillery 4 Falkirk Town Centre 5 FALKIRK 1 Callendar House JOHN MUIR WAY 2 Westquarter Glen GLEN VILLAGE To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE This tour of Falkirk’s surroundings takes in some of the most iconic landmarks in the area. Starting at Callendar Park, you’ll follow the John Muir Way past the impressive Callendar House before climbing through the huge trees of Callendar Wood to reach the Union Canal. Peeling off the canal (and leaving the John Muir Way), make your way to Westquarter Glen and pause at its peaceful waterfall before passing Falkirk Stadium on your way to the Helix with its famous Kelpies. After a tour of the giant sculptures and perhaps an indulgence in the café, you’ll pick up the Forth & Clyde Canal as far as Rosebank Distillery. A relaxed meander along Falkirk High St (and some well-earned refreshment in its selection of cafes and bistros) takes you back towards Callendar Park to complete the tour. The Kelpies ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 182m / Highest point 88m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Tour of Falkirk & The Kelpies PLACES OF INTEREST 1 CALLENDAR HOUSE Dating from the 14th century and set in the historic Callendar Park, the house featured in the TV series Outlander. Visit the exhibitions, Georgian kitchen and tearoom. WESTQUARTER GLEN 2 A peaceful little haven of pathways that follow Westquarter Burn as it meanders over a picturesque waterfall on its way towards Grangemouth. -

Tour of Falkirk and the Kelpies Walk

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Tour of Falkirk & The Kelpies ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 11.5 miles/18 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 4 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long but fairly flat 3 The Kelpies GRANGEMOUTH Rosebank Distillery 4 Falkirk Town Centre 5 FALKIRK 1 Callendar House JOHN MUIR WAY 2 Westquarter Glen GLEN VILLAGE To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE This tour of Falkirk’s surroundings takes in some of the most iconic landmarks in the area. Starting at Callendar Park, you’ll follow the John Muir Way past the impressive Callendar House before climbing through the huge trees of Callendar Wood to reach the Union Canal. Peeling off the canal (and leaving the John Muir Way), make your way to Westquarter Glen and pause at its peaceful waterfall before passing Falkirk Stadium on your way to the Helix with its famous Kelpies. After a tour of the giant sculptures and perhaps an indulgence in the café, you’ll pick up the Forth & Clyde Canal as far as Rosebank Distillery. A relaxed meander along Falkirk High St (and some well-earned refreshment in its selection of cafes and bistros) takes you back towards Callendar Park to complete the tour. The Kelpies ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 182m / Highest point 88m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Tour of Falkirk & The Kelpies PLACES OF INTEREST 1 CALLENDAR HOUSE Dating from the 14th century and set in the historic Callendar Park, the house featured in the TV series Outlander. Visit the exhibitions, Georgian kitchen and tearoom. WESTQUARTER GLEN 2 A peaceful little haven of pathways that follow Westquarter Burn as it meanders over a picturesque waterfall on its way towards Grangemouth. -

Falkirk Wheelhowierig

Planning Performance Framework Mains Kersie South South Kersie DunmoreAlloa Elphinstone The Pineapple Tower Westeld Airth Linkeld Pow Burn Letham Moss Higgins’ Neuk Titlandhill Airth Castle Castle M9 Waterslap Letham Brackenlees Hollings Langdyke M876 Orchardhead Blairs Firth Carron Glen Wellseld TorwoodDoghillock Drum of Kinnaird Wallacebank Wood North Inches Dales Wood Kersebrock Kinnaird House Bellsdyke of M9 Broadside Rullie River Carron Hill of Kinnaird Benseld M80 Hardilands The Docks Langhill Rosebank Torwood Castle Bowtrees Topps Braes Stenhousemuir Howkerse Carron Hookney Drumelzier Dunipace M876 North Broomage Mains of Powfoulis Forth Barnego Forth Valley Carronshore Skinats Denovan Chapel Burn Antonshill Bridge Fankerton Broch Tappoch Royal Hospital South Broomage Carron River Carron The Kelpies The Zetland Darroch Hill Garvald Crummock Stoneywood DennyHeadswood Larbert House LarbertLochlands Langlees Myot Hill Blaefaulds Mydub River Carron GlensburghPark Oil Renery Faughlin Coneypark Mungal Chaceeld Wood M876 Bainsford Wester Stadium Doups Muir Denny Castlerankine Grahamston Bankside Grangemouth Bo’ness Middleeld Kinneil Kerse Bonnyeld Bonny Water Carmuirs M9 Jupiter Newtown Inchyra Park Champany Drumbowie Bogton Antonine Wall AntonineBirkhill Wall Muirhouses Head of Muir Head West Mains Blackness Castle Roughcastle Camelon Kinneil House Stacks Bonnybridge Parkfoot Kinglass Dennyloanhead Falkirk Beancross Kinneil Arnothill Bog Road Wholeats Rashiehill Wester Thomaston Seabegs Wood Forth & Clyde Canal Borrowstoun Mains Blackness -

Westquarter Dovecot

Property in Care no: 330 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90311) Taken into State care: 1950 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE WESTQUARTER DOVECOT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH WESTQUARTER DOVECOT SYNOPSIS Westquarter Dovecot stands in Dovecot Road, Westquarter, a 1930s ‘garden suburb’ 2 miles ESE of Falkirk. The property comprises a fine dovecot of the rectangular or ‘lectern’ type. The heraldic panel above the entrance doorway displays the arms of Sir William Livingston of Westquarter and his wife, Helenore, and the date 1647. However, architectural details suggest a date early in the 18th century for its construction, and it seems likely that the armorial panel was brought here from elsewhere. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview: • 1503 – an Act of Parliament directs all lairds to erect ‘dowcats’ (pigeon houses) as a benefit to the community. • 1620s? – a mansion is built on the Westquarter (Wastquarter) estate, probably by Sir William Livingston and his wife, Dame Helenore. Westquarter House is depicted on Blaeu’s Atlas (1654). • 1650s - Sir William serves with his cousin and neighbour, James Livingston of Callendar, in the Royalist cause of Charles II against Oliver Cromwell. • 1701 – Westquarter passes to the Livingstons of Bedlormie (a village in West Lothian).