Countrystudy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Respuesta 105-2014-William Fernando Marroquín

IP-093-14-2015 En las instalaciones de la Unidad de Acceso a la Información Pública de LA ADMINISTRACIÓN NACIONAL DE ACUEDUCTOS Y ALCANTARILLADOS (ANDA): En la ciudad de San Salvador, a las catorce horas con cincuenta y cinco minutos del día doce de Octubre del año dos mil quince. La suscrita Oficial de Información CONSIDERANDO QUE: I) El día treinta de septiembre del presente año, se recibió mediante correo electrónico en la Unidad de Acceso a la Información Pública de ANDA (en adelante UAIP ANDA), solicitud de información por parte de la ciudadana: _______________, quien no se identificó por medio de ningún Documento de identidad personal, pero manifestó que era estudiante de la maestría de Centroamérica en Ciencias del Agua con énfasis en Calidad de Agua. UNAN/Managua. Y que para su proyecto de tesis está trabajando con el departamento Ambiental de la Alcaldía Municipal de Osicala, Morazán, que el título de la tesis es “Evaluación de la seguridad hídrica usando metología PSA, para la zona cafetalera de Osicala, Morazán, El Salvador, 2015-2016” los objetivos son: Estimar la disponibilidad Hídrica para la zona cafetalera de Osicala Morazán, El Salvador, 2015-2016. Evaluar el sistema de abastecimiento de agua con la metodología de plan de agua. Estimar la capacidad futura del sistema de agua potable en relación al crecimiento población y el efecto del cambio climático. Manifestó además que escribía para solicitar colaboración en la gestión de la siguiente información necesaria para realizar su trabajo de tesis: El proyecto en ArcGuis del mapa hidrogeológico de El Salvador, correspondiente a la zona de Morarán (Carolina). -

Morazan Sibasi Morazan

MINISTERIO DE SALUD PUBLICA Y ASISTENCIA SOCIAL DIRECCION DE PLANIFICACION DE LOS SERVICIOS DE SALUD 0 -1 IE UNIDAD DE INFORMACION EN SALUD C Red de Establecimientos de Salud funcionando, año 2006 DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZAN SIBASI MORAZAN T O T A L S I B A S I Hospitales 1 Unidades de Salud 25 Casas de Salud 12 Centros Rurales de Salud y Nutrición 5 T o t a l 43 ESTABLECIMIENTO DE SALUD MUNICIPIO Hospital Nacional General "Dr. Héctor Antonio Hernández Flores" San Francisco (Gotera) Unidad de Salud Arambala Arambala Unidad de Salud Cacaopera Cacaopera Unidad de Salud Corinto Corinto Unidad de Salud Chilanga Chilanga Unidad de Salud Delicias de Concepción Delicias de Concepción Unidad de Salud El Divisadero El Divisadero Unidad de Salud Gualococti Gualococti Unidad de Salud Guatajiagua Guatajiagua Unidad de Salud Joateca Joateca Unidad de Salud Jocoaitique Jocoaitique Unidad de Salud Jocoro Jocoro Unidad de Salud Lolotiquillo Lolotiquillo Unidad de Salud Meanguera Meanguera Unidad de Salud Osicala Osicala Unidad de Salud Perquín Perquín Fuente : Sistema Básico de Salud Integral (SIBASI) Página 1 de 2 MINISTERIO DE SALUD PUBLICA Y ASISTENCIA SOCIAL DIRECCION DE PLANIFICACION DE LOS SERVICIOS DE SALUD 0 -1 IE UNIDAD DE INFORMACION EN SALUD C Red de Establecimientos de Salud funcionando, año 2006 DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZAN SIBASI MORAZAN ESTABLECIMIENTO DE SALUD MUNICIPIO Unidad de Salud San Carlos San Carlos Unidad de Salud San Fernando San Fernando Unidad de Salud San Isidro San Isidro Unidad de Salud San Luis Meanguera Unidad de Salud San Simón -

Universidad De El Salvador Facultad Multidisciplinaria Oriental Departamento De Medicina Doctorado En Medicina

UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL DEPARTAMENTO DE MEDICINA DOCTORADO EN MEDICINA INFORME FINAL DE INVESTIGACIÓN: RELACIÓN DE LA ENFERMEDAD RENAL CRÓNICA Y EL CONTACTO OCUPACIONAL CON AGROQUÍMICOS H ERBICIDAS (FITO AMINA, PARAQUAT Y HEDONAL) UTILIZADOS EN CULTIVOS AGRÍCOLAS EN REGIONES SOBRE LOS 250 MSNM, EN LA POBLACIÓN DE 20 A 60 AÑOS DE EDAD QUE CONSULTA N EN LAS UNIDADES COMUNITARIAS DE SALUD F AMILIAR ESPECIALIZADAS CIUDAD BARRIOS, SAN MIGUEL, SENSEMBRA, MORAZÁN Y UNIDAD COMUNITARIA DE SALUD FAMILIAR INTERMEDIA GUALOCOCTI, MORAZÁN. AÑO 2016. PRESENTADO POR: SAMUEL ELIEZER ALVAREZ MELARA. GILMER MANFREDY HERNANDEZ CARRANZA. IRVIN JOSAEL ARGUETA ORELLANA. PARA OPTAR AL TÍTULO DE: DOCTOR EN MEDICINA. DOCENTE ASESOR: DR. RENÉ MERLOS RUBIO. NOVIEMBRE 2016 SAN MIGUEL, EL S AL VADOR, CENTRO AMÉRICA. AUTORIDADES UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR AUTORIDADES: LIC. JOS É LUIS ARGUETA ANTILLÓN RECTOR INTERINO . LIC. ROGER ARMANDO ÁR IAS. VICERRECTOR ACADÉMICO INTERINO . ING. CARLOS ARMAN DO VILLALTA. VICERR ECTOR ADMINISTRATIVO INTERINO . DRA. ANA LETICIA ZAVALETA DE AMAYA SECRETARI A GENERAL INTERINA . LICDA. NORA BEATRIZ MÉL E NDEZ . FISCAL GENERAL INTERINA. i AUTORIDADES DE FACULTAD MULTIDICIPLINARIA ORIENTAL. INGENIERO JOAQUÍN ORLANDO MACHUCA GÓMEZ . DECANO. LICENCIADO CARLOS ALEXANDER DÍAZ. VICEDECANO. MAESTRO JORGE ALBERTO ORTEZ HERNÁNDEZ. SECRETARIO . MAESTRO JORGE PASTOR FUENTES CABRERA. DIRECTOR GENERAL DEL PROCESO DE GRADUACIÓN ii DEPARTAMENTO DE MEDICINA: AUTORIDADES. DOCTOR FRANCISCO ANTONIO GUEVARA GARAY JEFE DE DEPARTAMENTO. MAESTRA ELBA MARGARITA BERRIOS CASTILLO. COORDINADORA GENERAL DE PROCESO DE GRADUACIÓN . iii ASESORES DE INVESTIGACIÓN. DR: RENÉ MERLOS RUBIO DOCENTE ASESOR MAESTRA ELBA MARGARITA BERRIOS CASTILLO. ASESORA DE METODOLOGÍA LIC. SIMÓN MARTINEZ DÍ AZ ASESOR DE ESTADÍ STICA. iv TRIBUNAL CALIFICADOR: DOCTOR HENRRY GEOVANNI MATA LAZO . -

La Dinámica Socio-Económica Del Territorio Microregión Osicala-Perquín

1 La Dinámica Socio-Económica del Territorio Microregión Osicala-Perquín: Social: Dentro de esta microregión nos referiremos a los municipios de Gualococti, Guatajiagua, Joateca, San Isidro y Torola, cinco municipios que aunque no presentan altos registros de eventos naturales como sismos, terremotos, inundaciones, sí presenta características socio-económicos que muestran altos niveles de vulnerabilidad. Estas características se agravan ante las malas prácticas antrópicas sobre el territorio, especialmente las agrícolas. Son municipios de población escasa, eminentemente rurales y altos índices de necesidades básicas insatisfechas (INBI). Para los municipios mencionados encontramos INBIs entre 57 y 62, siendo 80 el puntaje más alto que representa a aquellos municipios con más necesidades básicas insatisfechas. (Ver cuadro 1) CUADRO 1: Poblaciones Municipio N total N rural N Urbana Densidad Peso N Área Peso A INBI (hab/Km2) (km2) Gualococti 3356 2537 819 180.2 0.05 18.62 0.09 57 Guatajiagua 10941 6499 4442 154.6 0.16 70.77 0.34 59 Joateca 3907 3180 727 59 0.06 66.27 0.31 62 San Isidro 3463 2715 748 300.9 0.05 11.51 0.05 60 Torola 1575 1168 407 27 0.02 58.26 0.28 61 TOTAL 23242 16099 7143 0.34 1.07 FUENTE : EHPM, 2003 De los municipios identificados, aquel que tiene una mayor población es el de Joateca. Los municipios catalogados como de extrema pobreza severa tienen una población promedio de 3mil 075 habitantes, siendo estos municipios de muy poca población total. Son municipios donde el crecimiento de población ha sido relativamente bajo, y su total de población representa el 0.34% del total de la población de todo el país. -

Universidad De El Salvador Facultad Multidisciplinaria Oriental Departamento De Ingenieria Y Arquitectura

UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERIA Y ARQUITECTURA TRABAJO DE GRADO: PROPUESTA DE DISEÑO ARQUITECTONICO DEL PARQUE ECOLOGICO “BAILADERO DEL DIABLO” PERQUIN, MORAZAN. PRESENTADO POR: MARLEN SARAI CLAROS VIGIL. GLORIA MARIELA GONZALEZ DE CRUZ. PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: ARQUITECTA. DOCENTE DIRECTOR: ARQ. JAVIER REINIERY ABREGO DEL CID. CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA ORIENTAL, 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR AUTORIDADES RECTOR: ING. MARIO ROBERTO NIETO LOVO VICERECTOR ACADEMICA: MS.D ANA MARIA GLOWER DE ALVARADO SECRETARIO GENERAL: DR. ANA LETICIA ZAVALETA DE AMAYA FISCAL GENERA: LIC. FRANCISCO CRUZ LETONA AUTORIDADES FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL DECANO: LIC. CRISTOBAL HERNAN RIOS BENITEZ VICE DECANO: LIC. CARLOS ALEXANDER DIAZ SECRETARIO: LIC. JORGE ALBERTO ORTEZ HERNANDEZ UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERIA Y ARQUITECTURA TRABAJO DE GRADO: PROPUESTA DE DISEÑO ARQUITECTONICO DEL PARQUE ECOLOGICO “BAILADERO DEL DIABLO” PERQUIN, MORAZAN. PRESENTADO POR: MARLEN SARAI CLAROS VIGIL. GLORIA MARIELA GONZALEZ DE CRUZ. PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: ARQUITECTA. Trabajo de graduación aprobado por: DOCENTE DIRECTOR DEL PROYECTO: ARQ. JAVIER REINIERY ABREGO DEL CID. SAN MIGUEL, 21 ENERO DE 2015 TRABAJO DE GRADUACION APROBADO POR: DOCENTE DIRECTOR: ARQ. JAVIER REINIERY ABREGO DEL CID COORDINADORA DEL PROCESO DE TESIS: ING. MILAGRO BARDALES DE GARCIA INDICE Contenido 1.1 PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA. ........................................................................................ -

Peace Agreements Digital Collection El Salvador >> Peace Agreement >> Annexes to Chapter VII

Peace Agreements Digital Collection El Salvador >> Peace Agreement >> Annexes to Chapter VII Annexes to Chapter VII Table of Contents Annex A Annex B Annex C Annex D Annex E Annex F Annex A Places where FAES forces shall be concentrated by D-Day + 5 A. Ahuachacan 1. Llano del Espino, Beneficio Agua Chica and Geotérmica Ausoles (Ausoles geothermal station) and Finca San Luis 2. Beneficio Molino, Beneficio Sta. Rita, Repetidora Apaneca (Apaneca relay station), Puente Sunzacate, Finca Alta Cresta 3. Military Detachment No. 7 (DM-7) B. Sonsonate 4. Complejo Industrial Acajutla (Acajutla industrial complex), Puente Hacienda Km 5, Puente Río Bandera 5. Military Detachment No. 6 (DM-6) C. Santa Ana 6. Beneficio Tazumal, Beneficio Venecia, Beneficio La Mia and Cerro Singüil 7. Planta San Luis Uno and San Luis Dos 8. El Rodeo 9. Sitio Plan El Tablón 10. Cerro El Zacatío 11. Santa Rosa Huachipilín 12. Banderas 13. Cerro El Zacamil 14. Second Brigade D. Chalatenango 15. Cantón and Caserío El Encumbrado (El Encumbrado canton and hamlet) 16. Cantón and Caserío Potrero Sula (Potrero Sula canton and hamlet) 17. Cantón and Caserío El Carrizal (El Carrizal canton and hamlet) 18. San Rafael 19. La Laguna 20. Concepción Quezaltepeque 21. Potonico 22. Fourth Infantry Brigade 23. Military Detachment No. 1 (DM-1) 24. El Refugio base E. La Libertad 25. Presa San Lorenzo (San Lorenzo dam), Beneficio Río Claro and Beneficio Atapasco 26. San Juan de los Planes 27. Cantón and Caserío Las Granadillas (Las Granadillas canton and hamlet) 28. ESTRANFA (Transport Unit) 29. Artillery Brigade 30. Atlacatl BIRI (Rapid Deployment Infantry Brigade) 31. -

Municipio De Cacaopera, Departamento De Morazan

MUNICIPIO DE CACAOPERA, DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZAN “CAPACITACIÓN Y ASISTENCIA TÉCNICA PARA LA FORMULACIÓN Y SEGUIMIENTO DEL PLAN ESTRATÉGICO PARTICIPATIVO PARA EL MUNICIPIO DE CACAOPERA”. CODIGO 255840 “PLAN ESTRATÉGICO PARTICIPATIVO PARA EL MUNICIPIO DE CACAOPERA”. FASE III PASO 11 ELABORADO POR: FUNDACIÓN DE EDUCACIÓN POPULAR CIAZO JULIO 2013 INDICE PRESENTACION ............................................................................................................ 4 CONCEJO MUNICIPAL 2012-2015 ............................................................................... 6 INSTANCIA DE PARTICIPACION PERMANENTE (IPP) ......................................... 7 AUSPICIANTES, PARTICIPANTES Y FACILITADORES ......................................... 8 CAPÍTULO I: INFORMACIÓN GENERAL DEL MUNICIPIO ................................. 10 1.1 Ficha básica del municipio. ...................................................................................... 10 1.2 Síntesis Histórica. ..................................................................................................... 11 1.3 Hitos Históricos. ....................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Datos culturales. ....................................................................................................... 11 1.5 El Municipio en el Departamento y en El Salvador. ................................................ 12 1.6 Equipamiento en el municipio. ................................................................................ -

Cultad Multidisciplinaria Oriental Departamento De Ingenieria Y Arquitectura

UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERIA Y ARQUITECTURA TRABAJO DE GRADO: “APLICACIÓN DE SIG PARA LA GESTION DEL LEVANTAMIENTO CATASTRAL DEL MUNICIPIO DE CHILANGA DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZÁN”. PRESENTADO POR: GUEVARA ARGUETA, CARLOS OSMEL PONCE RAMOS, JOSE MAURICIO RÍOS DÍAZ, ROXANA LIZETH PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: INGENIERO CIVIL DOCENTE DIRECTOR ING. UVIN EDGARDO ZUNIGA CRUZ CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA ORIENTAL, SEPTIEMBRE DE 2017 SAN MIGUEL EL SALVADOR CENTROAMERICA UNIVERSIDAD DE EL SALVADOR AUTORIDADES RECTOR: M. SC. ROGER ARMANDO ARIAS VICE-RECTOR ADMINISTRATIVO: ING. NELSON BERNABE GRANADOS SECRETARIO GENERAL: M. SC. CRISTOBAL RIOS FACULTAD MULTIDISCIPLINARIA ORIENTAL AUTORIDADES DECANO: ING. JOAQUIN ORLANDO MACHUCA GOMEZ VICE-DECANO: LIC. CARLOS ALEXANDER DIAZ SECRETARIO: LIC. JORGE ALBERTO ORTEZ HERNANDEZ JEFE DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERIA Y ARQUITECTURA: ING. JUAN ANTONIO GRANILLO COREAS AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios, que nos llena de bendiciones día con día y nos entrega la sabiduría para alcanzar nuestras metas y nos mueve a cumplir todos nuestros planes. A mis padres, porque son el principal apoyo en todos mis proyectos y me han formado como una persona de bien, gracias por ser estrictos cuando era necesario y por demostrarme su amor. A mis compañeros de tesis, que también son mis amigos gracias por estos años en los que hemos crecido juntos como personas, por todas las veces que me obligaron a trabajar y estudiar para ponerme al día, por las salidas “obligatorias” para regular nuestro estrés, gracias por todo compañeros. A todos mis amigos músicos, gracias muchachos por enseñarme y por aceptarme en sus vidas, gracias por todas las horas que pasamos aprendiendo juntos y mejorando nuestras habilidades, eso me ha servido mucho para tener disciplina en todos los aspectos de mi vida, gracias y a seguir aprendiendo. -

No. 3. Año I. El Salvador, C.A., May 1 1984.

SEMANARIO DE ANALISIS POLITICO Director Alfonso Quijada U rias No. 3. Año I. El Salvador, C.A., May 1 1984. that we Ould authorize him to carry out preventive mili- tary operations against what he calls "terrorism". But To ourpeople and all the peoples of the world what is really at issue is legitimizing state terrorism on a world level, something Washington is involved in up to its ears. Before the people of the United States, the FMLN declares: the path taken by Reagan has reached the F.M.L.N. COMMUNIQUThe victor will be whoever is imposed through this point that a choice must be made between accepting THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT struggle taking place behind the backs of the Salvadoran the FMLN's proposal for dialogue and negotiation, PRESSURED THE SALVADORAN GOVERN- people, who have never had a genuine opportunity to teading to the establishment of a broadly based provi- elect their rulers. Once again the vote will be a farce, MENT, RIGHT—WING POLITICAL PARTIES, sional government, or carrying out against our country a and the government that emerges will have to follow the military intervention that is more direct and more AND PUPPET ARMED FORCES TO HOLD dictates of Yankee imperialista. Reagan has already raid massive than the present intervention, It has already PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS. THE AIM WAS that he will support any president, including one put in been shown that the dictatordiip's army is incapable of TO AID REAGAN IN HIS CAMPAING FOR power by a coup, and that the will continue pressing defeating us and is clearly losing the war, despite ahead with his plan of war for El Salvador and Central REELECTION AND TO GIVE POLITICAL Washington's multimillion dollar support and advisers. -

59-60-61-62-63-64-55-Ape-2019 Cámara Especializada De Lo

59-60-61-62-63-64-55-APE-2019 CÁMARA ESPECIALIZADA DE LO PENAL, Santa Tecla, Departamento de La Libertad, a las quince horas con trece minutos del día veintiséis de septiembre del año dos mil diecinueve. 59 a 65-APE-2019 (13). Por recibido el día treinta de enero del año dos mil diecinueve, en la Secretaría de esta Cámara el oficio N° 222 de fecha veintiocho de ese mismo mes y año, proveniente del Juzgado Especializado de Sentencia de San Miguel, por medio del cual remiten con 4586 Fs, el proceso penal instruido en contra de los imputados: 1) SCPP, alias “CH***” de veintiún años de edad, hijo de ******** y ********, residente en ********, jurisdicción de Yoloaquin, Departamento de Morazán; 2) NMAM, alias “El G***” de diecinueve años de edad, soltero, jornalero, con fecha de nacimiento el veintisiete de noviembre de mil novecientos noventa y seis, originario y residente en ********, Jocoaitique Morazán. 3) BASG alias “B***” de veinte años de edad, cabello negro, piel morena delgado, hijo de ******** y ********, r000esidente en ******** municipio de Yoloaiquin. 4) GASG alias “LA M***”, de treinta y cuatro años de edad, de fecha de nacimiento treinta de septiembre del año mil novecientos ochenta y dos, soltero, cabello negro, piel morena, ojos café, ayudante de albañil, hijo de ******** y ********. 5) GAD alias “M***” de veintisiete años de edad, soltero, sin oficio, hijo de ********, residente en ******** Jocoaitique Morazán; imputados a quienes se les atribuye el delito de ORGANIZACIONES TERRORISTAS previsto y sancionado en el Art. 13 de la Ley Especial contra Actos de Terrorismo en perjuicio de la SEGURIDAD DEL ESTADO. -

TS-051-16 TRIBUNAL DE SENTENCIA, SAN FRANCISCO GOTERA, DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZAN , a Las Ocho Horas Con Treinta Minutos Del Día Diecinueve De Julio De Dos Mil Dieciséis

TS-051-16 TRIBUNAL DE SENTENCIA, SAN FRANCISCO GOTERA, DEPARTAMENTO DE MORAZAN , a las ocho horas con treinta minutos del día diecinueve de julio de dos mil dieciséis. A partir de las diez horas del día cinco de julio del presente año, se instaló la Vista Pública, en la que el suscrito Juez designado, Licenciado OSCAR RENE ARGUETA ALVARADO, conoció en forma Unipersonal sobre la causa penal número TS 051/2016, que se instruye contra el imputado detenido, señor RAFAEL ANTONIO B. G., alias [...] , de veintiocho años de edad, soltero, jornalero, hijo de [...] y [...], originario de Gualococti y residente en el Cantón [...], Jurisdicción de Gualococti, Departamento de Morazán, procesado por el delito de SECUESTRO, tipificado en el Art. 149 del Código Penal, en perjuicio de la víctima con Régimen de Protección identificada con la clave “ROMEO” ; audiencia en la que participaron como Representantes del Fiscal General de la República, las Licenciadas ADA LORENA H. DE S. y JENNY LOURDES R. DE M. y como Defensor Público del imputado, el Licenciado MARIO SERGIO C. C.- Y CONSIDERANDO: I- Que el día veintitrés de noviembre del año dos mil once, la Licenciada Rosa Antonia L. de A. , en su calidad de Agente Auxiliar del Fiscal General de la República, presentó ante el señor Juez Especializado de Instrucción de la ciudad de San Miguel, el dictamen de acusación en contra del señor Rafael B., alias [...] y otros imputándoles el delito de Secuestro, tipificado en el Art. 149 Pn y ROBO AGRAVADO, tipificado en los Arts. 212 en relación con el Art. 213 Nº 2 Pn ambos delitos en perjuicio de la víctima denominada con clave “ROMEO”; sosteniendo en el referido dictamen como relación circunstanciada de los hechos, la siguiente: “Que los hechos investigados dan inicio con reuniones previas realizadas por parte del testigo “ELOISA” junto a JOSE ANTONIO V. -

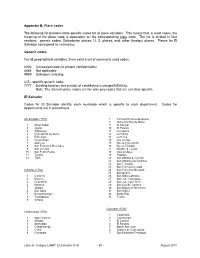

Appendix B: Place Codes the Following List Provides State-Specific

Appendix B: Place codes The following list provides state-specific codes for all place variables. This means that, in most cases, the meaning of the place code is dependent on the corresponding state code. The list is divided in four sections: generic codes; Salvadorian places; U. S. places; and, other (foreign) places. Places for El Salvador correspond to municipios. Generic codes For all geographical variables, there exist a set of commonly used codes: 0000 Concealed code (to protect confidentiality) 8888 Not applicable 9999 Unknown / missing U.S.- specific generic code: 7777 Existing location, but outside of established municipio/MSA/city. Note: The Generic place codes are the only geo-codes that are not state-specific. El Salvador Codes for El Salvador identify each municipio which is specific to each department. Codes for departments are in parenthesis. Ahuachapán (1701) 7 Concepción Quezaltepeque 8 Dulce Nombre de María 1 Ahuachapán 9 El Carrizal 2 Jujutla 10 El Paraíso 3 Atiquizaya 11 La Laguna 4 Concepción de Ataco 12 La Palma 5 El Refugio 13 La Reina 6 Guaymango 14 Las Vueltas 7 Apaneca 15 Nueva Concepción 8 San Francisco Menéndez 16 Nueva Trinidad 9 San Lorenzo 17 Nombre de Jesús 10 San Pedro Puxtla 18 Ojos de Agua 11 Tacuba 19 Potonico 12 Turín 20 San Antonio de la Cruz 21 San Antonio Los Ranchos 22 San Fernando 23 San Francisco Lempa Cabañas (1702) 24 San Francisco Morazán 25 San Ignacio 1 Cinquera 26 San Isidro Labrador 2 Dolores 27 San José Cancasque 3 Guacotecti 28 San José Las Flores 4 Ilobasco 29 San Luis del Carmen 5