World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

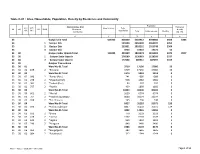

Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community

Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community Population Administrative Unit Population UN / MZ / Area in Acres Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence density WA MH Households Community Total In Households Floating [sq. km] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 33 Gazipur Zila Total 446363 826458 3403912 3398306 5606 1884 33 1 Gazipur Zila 565903 2366338 2363287 3051 33 2 Gazipur Zila 255831 1018252 1015748 2504 33 3 Gazipur Zila 4724 19322 19271 51 33 30 Gazipur Sadar Upazila Total 113094 449139 1820374 1815303 5071 3977 33 30 1 Gazipur Sadar Upazila 276589 1130963 1128206 2757 33 30 2 Gazipur Sadar Upazila 172550 689411 687097 2314 33 30 Gazipur Paurashava 33 30 01 Ward No-01 Total 3719 17136 17086 50 33 30 01 169 2 *Bhurulia 3719 17136 17086 50 33 30 02 Ward No-02 Total 1374 5918 5918 0 33 30 02 090 2 *Banua (Part) 241 1089 1089 0 33 30 02 248 2 *Chapulia (Part) 598 2582 2582 0 33 30 02 361 2 *Faokail (Part) 96 397 397 0 33 30 02 797 2 *Pajulia 439 1850 1850 0 33 30 03 Ward No-03 Total 10434 40406 40406 0 33 30 03 661 2 *Mariali 1629 6574 6574 0 33 30 03 797 2 *Paschim Joydebpur 8660 33294 33294 0 33 30 03 938 2 *Tek Bhararia 145 538 538 0 33 30 04 Ward No-04 Total 8427 35210 35071 139 33 30 04 496 2 *Purba Joydebpur 8427 35210 35071 139 33 30 05 Ward No-05 Total 3492 14955 14955 0 33 30 05 163 2 *Bhora 770 3118 3118 0 33 30 05 418 2 *Harinal 1367 6528 6528 0 33 30 05 621 2 *Lagalia 509 1823 1823 0 33 30 05 746 2 *Noagaon 846 3486 3486 0 33 30 06 Ward No-06 Total 1986 8170 8170 0 33 30 06 062 2 *Bangalgachh 382 1645 1645 0 33 30 06 084 2 *Baluchakuli 312 1244 1244 0 RMO: 1 = Rural, 2 = Urban and 3 = Other Urban Page 1 of 52 Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community Population Administrative Unit Population UN / MZ / Area in Acres Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence density WA MH Households Community Total In Households Floating [sq. -

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Mapping Exercise on Water- Logging in South West of Bangladesh

MAPPING EXERCISE ON WATER- LOGGING IN SOUTH WEST OF BANGLADESH DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS March 2015 I Preface This report presents the results of a study conducted in 2014 into the factors leading to water logging in the South West region of Bangladesh. It is intended to assist the relevant institutions of the Government of Bangladesh address the underlying causes of water logging. Ultimately, this will be for the benefit of local communities, and of local institutions, and will improve their resilience to the threat of recurring and/or long-lasting flooding. The study is intended not as an end point, but as a starting point for dialogue between the various stakeholders both within and outside government. Following release of this draft report, a number of consultations will be held organized both in Dhaka and in the South West by the study team, to help establish some form of consensus on possible ways forward, and get agreement on the actions needed, the resources required and who should be involved. The work was carried out by FAO as co-chair of the Bangladesh Food Security Cluster, and is also a contribution towards the Government’s Master Plan for the Agricultural development of the Southern Region of the country. This preliminary work was funded by DfID, in association with activities conducted by World Food Programme following the water logging which took place in Satkhira, Khulna and Jessore during late 2013. Mike Robson FAO Representative in Bangladesh II Mapping Exercise on Water Logging in Southwest Bangladesh Table of Contents Chapter Title Page no. -

Taxonomic Enumeration of Angiosperm Flora of Sreenagar Upazila, Munshigang, Dhaka, Bangladesh

J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh, Sci. 43(2): 161-172, December 2017 TAXONOMIC ENUMERATION OF ANGIOSPERM FLORA OF SREENAGAR UPAZILA, MUNSHIGANG, DHAKA, BANGLADESH ZAKIA MAHMUDAH, MD. MUZAHIDUL ISLAM, TAHMINA HAQUE AND MOHAMMAD ZASHIM UDDIN1 Department of Botany, University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Abstract The present article focuses the status of angiosperm flora of Sreenagar upazila under Munshiganj district. The study was done from July 2015 to June 2016. A total of 219 plant species of angiosperms was identified belonging to 165 genera and 70 families. Among them 38 species were monocotyledons and 181 plant species were dicotyledons. Herbs were the largest life forms among the angiosperms and contained about 58% of total plant species occurring in this area. Trees and shrubs occupied 23% and 12% respectively. Climbers were 6% but epiphytes (1%) were very negligible in number in the study area. About 51 medicinal plants were recorded from this study. The following species viz. Lasia spinosa, Calamus tenuis, Tinospora crispa, Passiflora foetida and Calotropis procera were recorded only once and hence considered as rare species in Sreenagar upazila. An invasive poisonous plant Parthenium hysterophorus was also found in Sreenagar. Key words: Diversity, Angiosperm flora, Sreenagar, Munshiganj district Introduction Sreenagar is an upazila under Munshiganj district situated on the bank of ‘Padma’ river. It is a part of Dhaka division, located in between 23°27' and 23°38' north latitudes and in between 90°10' and 90°22' east longitudes. The total area is 202, 98 square kilometer and bounded by Serajdikhan and Nawabganj upazilas on the north, Lohajong and Shibchar upazilas on the south, Serajdikhan and Nawabganj and Dohar upazilas on the west. -

57 47 01 096 2 *Banshbaria Dakshin Para 350 186 164 171 1 0 0 1

Table C-10: Distribution of Population aged 7 years and above not attending school by Employment Status, Sex, Residence and Community Employment Status Administrative Unit Population aged 7+ and not UN / MZ / ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence attending school Employed Looking for work Household work Do not work WA MH Community Both Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 57 Meherpur Zila Total 230121 110699 119422 98340 3162 383 222 692 102455 11284 13583 57 1 Meherpur Zila 211904 102347 109557 91261 2632 363 201 632 94669 10091 12055 57 2 Meherpur Zila 14056 6342 7714 5300 496 18 15 29 5946 995 1257 57 3 Meherpur Zila 4161 2010 2151 1779 34 2 6 31 1840 198 271 57 47 Gangni Upazila Total 116279 56215 60064 49999 1648 207 120 391 52038 5618 6258 57 47 1 Gangni Upazila 108304 52459 55845 46691 1517 196 114 356 48434 5216 5780 57 47 2 Gangni Upazila 6339 2975 3364 2606 117 10 4 14 2842 345 401 57 47 3 Gangni Upazila 1636 781 855 702 14 1 2 21 762 57 77 57 47 Gangni Paurashava 6339 2975 3364 2606 117 10 4 14 2842 345 401 57 47 01 Ward No-01 Total 825 423 402 386 10 0 0 1 371 36 21 57 47 01 096 2 *Banshbaria Dakshin Para 350 186 164 171 1 0 0 1 153 14 10 57 47 01 097 2 *Banshbaria Paschimpara 121 62 59 60 0 0 0 0 57 2 2 57 47 01 098 2 *Banshbaria Uttarpara 142 70 72 62 1 0 0 0 67 8 4 57 47 01 329 2 *Banshbaria Purbapara 105 46 59 38 5 0 0 0 52 8 2 57 47 01 337 2 *Jhinirpul Para 107 59 48 55 3 0 0 0 42 4 3 57 47 02 Ward No-02 Total 724 329 395 286 14 0 1 5 330 38 50 57 47 02 298 2 *Chuagachha Cinema -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

INTEGRATING LAND with WATER ROUTES: Proposal for a Sustainable Spatial Network for Keraniganj in Dhaka

Proceedings of the Ninth International Space Syntax Symposium Edited by Y O Kim, H T Park and K W Seo, Seoul: Sejong University, 2013 INTEGRATING LAND WITH WATER ROUTES: Proposal for a sustainable spatial network for Keraniganj in Dhaka Farida Nilufar 031 Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology e-mail : [email protected] Labib Hossain Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology e-mail : [email protected] Mahbuba Afroz Jinia Stamford University Bangladesh e-mail : [email protected] Abstract Cities in the delta have unique spatial character being criss-crossed by rivers and canals. Keraniganj Upazila of Dhaka District is a settlement surrounded by two big rivers which are again connected by a canal network. The spatial network of Keraniganj, therefore, has got some significance due to its connectivity with the water-ways. However, as a result of many insentient manmade efforts, the water-ways of this settlement did not developed to any integrated system with the surface routes. Canals are being used as drainage channels or being filled up. Moreover, seasonal floods have detrimental effects on the land-use and infrastructure. As a result the potential development of Keraniganj is being hampered. A new land-use proposal under Detailed Area Plan (DAP) is in process of implementation. Besides, the inhabitants are trying to develop their own solution through a number of local roads. None of them, the professionals or the locals, ever takes the challenge to live negotiating with nature. It appears that the spatial characteristics of the existing and proposed network need to be explored in order to evolve a sustainable spatial network for Keraniganj. -

Document of the World Bank

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR000028 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (IDA-31240 SWTZ-21082) ON A Public Disclosure Authorized CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 24.2 MILLION (US$ 44.4 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO BANGLADESH FOR ARSENIC MITIGATION WATER SUPPLY Public Disclosure Authorized June 10, 2007 Sustainable Development Department Environment and Water Resources Unit SOUTH ASIA REGION Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange rate effective: Average during project duration Currency unit = Taka (Tk) Tk 1.00 = US$ 0.016 US$ 1.00 = Tk 59.1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APL adaptable program loan BAEC Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission BAMWSP Bangladesh Arsenic Mitigation Water Supply Project BWSPP Bangladesh Water Supply Program Project DANIDA Danish International Development Agency DFID Department for International Development (UK) DPHE Department of Public Health Engineering GPS global positioning system IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency ICR Implementation Completion and Results Report ISR Implementation Status and Results Report MoU memorandum of understanding NAMIC National Arsenic Mitigation Information Center NWSSIC National Water Supply and Sanitation Information Center PDO project development objective PMU Project Management Unit SDC Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SIL specific investment loan UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WAMWUG ward arsenic mitigation water user group WSP Water and Sanitation Program Vice President: Praful Patel Country Director: Xian Zhu Sector Director: Constance Bernard Project Team Leader: Karin Erika Kemper ICR Team Leader: Karin Erika Kemper People’s Republic of Bangladesh Arsenic Mitigation Water Supply Project CONTENTS Data Sheet A. Basic Information…………………………………………………………………………... i B. Key Dates…………………………………………………………………………………... i C. -

Invitation for E-Tender (LTM)-Furniture-1St

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER EDUCATION ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT, NARAYANGANJ ZONE SHIKKHA BHABAN, MASDAIR, NARAYANGANJ [email protected] Memo No: 13/EED/NZ/2019-20/1666 Date: 25/07/2019 Invitation for e-Tender (LTM)-Furniture-1st SL Last Selling Last Closing Tender ID No. Name of Works no Date & Time Date & Time Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 1 345932 Selected Firoza Khatun Adarsha Mohila Dakhil Madrasha, Sadar 17:00 16:00 Upazila, Narayanganj District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 2 345930 Selected Darussunnah Kamil Madrasha, Fatullah, Sadar Upazila, 17:00 16:00 Narayanganj District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 3 345929 Selected Shadipur Islamia Senior Alim Madrasha, Sonargano Upazila, 17:00 16:00 Narayanganj District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 4 345928 Selected Beldi Darul Hadis Fazil Madrasha, Rupganj Upazila, 17:00 16:00 Narayanganj District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 5 345927 Selected Narayanganj High School, Sadar Upazila, Narayanganj 17:00 16:00 District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 6 345926 Selected Hazi Pande Ali High School, Fatullah, Sadar Upazila, 17:00 16:00 Narayanganj District. Manufacturing and Supplying of furniture for Academic building to 19-Aug-2019 20-Aug-2019 7 345925 Selected Godnail High School, Shiddirganj, Sadar Upazila, Narayanganj 17:00 16:00 District. -

Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER EDUCATION ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT, NARAYANGANJ ZONE SHIKKHA BHABAN, MASDAIR, NARAYANGANJ [email protected] Memo No: 74/EED/NZ/2019-20/2328 Date: 18/12/2019 Invitation for e-Tender LTM (5974-2nd) Name of Project: Repair/Renovation of Non-Govt. Educational Institutions. SL Tender ID Last Selling Last Closing Name of Works no No. Date & Time Date & Time Repair & Renovation Works of 02-Storied Academic Building at 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 1 399803 Malkhanagar Dakhil Madrasha Sirjdikhan Upazila Munshiganj 17:00 12:00 District. Repair & Renovation Works of Single Storied Academic Building & 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 2 399802 Office Room at Rasulpur Islamia Dakhil Madrasah Louhajang Upazila 17:00 12:00 Munshiganj District. Repair & Renovation Works at Beltoli G J High School Sreenagar 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 3 399801 Uapzila Munshiganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works at Kamargaon Adarsha School Sreenagar 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 4 399799 Upazila Munshiganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works 02-Storied Academic Building at 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 5 399798 Malopdia Adarsha High School Sirajdikhan Upazila Munshiganj 17:00 12:00 District. Repair & Renovation Works of 02-Storied Academic Building at 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 6 399797 Shekhornagar Girls High School Sirajdikhan Upazila Munshiganj 17:00 12:00 District. Repair & Renovation Works of Single Storied Academic Building at 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 7 399796 Bikrampur Adarsha College Sirajdikhan Upazila Munshiganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Three Storied Academic Building at 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 8 399795 Ali Asgar and Abdullah Degree College Sirajdikhan Upazila 17:00 12:00 Munshiganj District Repair & Renovation Works of Boundary Wall at Brahammangaon M 15-Jan-2020 16-Jan-2020 9 399794 L High School Lauhaganj Upazila Munshiganj District. -

Bounced Back List.Xlsx

SL Cycle Name Beneficiary Name Bank Name Branch Name Upazila District Division Reason for Bounce Back 1 Jan/21-Jan/21 REHENA BEGUM SONALI BANK LTD. NA Bagerhat Sadar Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 23-FEB-21-R03-No Account/Unable to Locate Account 2 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUR RAHAMAN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SHEIKH 3 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOKTADIR HOSEN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 4 Jan/21-Jan/21 BADSHA MIA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 5 Jan/21-Jan/21 MADHAB CHANDRA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SINGHA 6 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUL ALI UKIL SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 7 Jan/21-Jan/21 MRIDULA BISWAS SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 8 Jan/21-Jan/21 MD NASU SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 9 Jan/21-Jan/21 OZIHA PARVIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 10 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOHASHIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 11 Jan/21-Jan/21 FAHAM UDDIN SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 12 Jan/21-Jan/21 JAFAR SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. -

Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER EDUCATION ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT, NARAYANGANJ ZONE SHIKKHA BHABAN, MASDAIR, NARAYANGANJ [email protected] Memo No: 470/EED/NZ/2018-19/882 Date: 05/03/2019 Invitation for e-Tender (5974-3rd) SL Tender ID Last Selling Last Closing Name of Works no No. Date & Time Date & Time Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Araihazar Emdadul 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 1 291052 Ulum Alim Madrasha, Araihazar Upazila, Narayanganj Distrcit. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Kalapaharia Union High 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 2 291051 School, Araihazar Upazila, Narayanganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Kalagacia R F High 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 3 291050 School, Araihazar Upazila, Narayanganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Purbokandi Adarsha 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 4 291049 Dakhil Madrasha, Araihazar Upazila, Narayanganj District. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Nagar Dokadi 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 5 291048 Madrasha, Araihazar Upazila, Narayanganj Distrcit. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Dapa Adarsha High 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 6 291046 School, Sadar Upazila, Narayanganj Distrcit. 17:00 12:00 Repair & Renovation Works of Academic Building at Jalkuri Islamia Dakhil 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 7 291045 Madrasha, Sadar Upazila, Narayanganj District. 17:00 12:00 Ground Floor Hight Extension & Other Repair & Renovation Works at 20-Mar-2019 21-Mar-2019 8 291044 Mizmizi Poshimpara High School, Sadar Upazila, Narayanganj District.