The Case of Bangladesh D National Se

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security and Social Safety Net Programs in Rural Bangladesh

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty? Food Security and Social Safety Net Programs in Rural Bangladesh K M Kabirul Islam A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Policy Research Centre Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of New South Wales July 2016 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Islam First name: K M Kabirul Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Social Policy Research Centre Faculty: Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Title: Is the glass half full or half empty? Food security and social safety net programs in rural Bangladesh Despite achieving self-sufficiency in food production in the late 1990s, food security is still a major policy issue in Bangladesh due to lack of access to safe and sufficient food for the poor. Consecutive governments have developed a range of social safety net programs (SSNPs) to address the issue. A number of studies have been conducted to assess these programs' impact on ensuring food security; however, the poorest people were not widely engaged in previous studies, nor in the design or implementation of the programs. This research explored the perceptions, insights and experiences of people in one of the poorest rural areas of Bangladesh. Two groups of people were interviewed: the beneficiaries of five selected SSNPs and non-beneficiaries who would have qualified for a program. This research focuses on exploring how people perceive their food security issues and how these issues could be solved to improve their lives. -

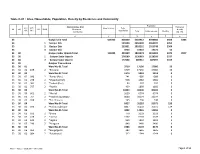

Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community

Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community Population Administrative Unit Population UN / MZ / Area in Acres Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence density WA MH Households Community Total In Households Floating [sq. km] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 33 Gazipur Zila Total 446363 826458 3403912 3398306 5606 1884 33 1 Gazipur Zila 565903 2366338 2363287 3051 33 2 Gazipur Zila 255831 1018252 1015748 2504 33 3 Gazipur Zila 4724 19322 19271 51 33 30 Gazipur Sadar Upazila Total 113094 449139 1820374 1815303 5071 3977 33 30 1 Gazipur Sadar Upazila 276589 1130963 1128206 2757 33 30 2 Gazipur Sadar Upazila 172550 689411 687097 2314 33 30 Gazipur Paurashava 33 30 01 Ward No-01 Total 3719 17136 17086 50 33 30 01 169 2 *Bhurulia 3719 17136 17086 50 33 30 02 Ward No-02 Total 1374 5918 5918 0 33 30 02 090 2 *Banua (Part) 241 1089 1089 0 33 30 02 248 2 *Chapulia (Part) 598 2582 2582 0 33 30 02 361 2 *Faokail (Part) 96 397 397 0 33 30 02 797 2 *Pajulia 439 1850 1850 0 33 30 03 Ward No-03 Total 10434 40406 40406 0 33 30 03 661 2 *Mariali 1629 6574 6574 0 33 30 03 797 2 *Paschim Joydebpur 8660 33294 33294 0 33 30 03 938 2 *Tek Bhararia 145 538 538 0 33 30 04 Ward No-04 Total 8427 35210 35071 139 33 30 04 496 2 *Purba Joydebpur 8427 35210 35071 139 33 30 05 Ward No-05 Total 3492 14955 14955 0 33 30 05 163 2 *Bhora 770 3118 3118 0 33 30 05 418 2 *Harinal 1367 6528 6528 0 33 30 05 621 2 *Lagalia 509 1823 1823 0 33 30 05 746 2 *Noagaon 846 3486 3486 0 33 30 06 Ward No-06 Total 1986 8170 8170 0 33 30 06 062 2 *Bangalgachh 382 1645 1645 0 33 30 06 084 2 *Baluchakuli 312 1244 1244 0 RMO: 1 = Rural, 2 = Urban and 3 = Other Urban Page 1 of 52 Table C-01 : Area, Households, Population, Density by Residence and Community Population Administrative Unit Population UN / MZ / Area in Acres Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence density WA MH Households Community Total In Households Floating [sq. -

(Bangladesh) (PDF

PARTICIPANTS’111TH INTERNATIONAL PAPERS SEMINAR PARTICIPANTS’ PAPERS THE ROLE OF POLICE, PROSECUTION AND THE JUDICIARY IN THE CHANGING SOCIETY Rebeka Sultana* I. INTRODUCTION resentment due to uneven economic prosperity; unstable public order Crime prevention means the elimination intensified by feud, illiteracy, of criminal activity before it occurs. unemployment etc, as the fundamental Prevention of crime is being effected/ causes of the high escalation of crime in enforced with the help of preventive Bangladesh. prosecution, arrest, surveillance of bad characters etc by the law enforcing Due to radical changes taking place in agencies of the country concerned. Crime, the livelihood of people in the recent past, and the control of crime throughout the criminals have also brought remarkable world, has been changing its features changes in their style of operation in rapidly. Critical conditions are taking place committing crimes. The crime preventive/ when there is change. Nowdays, causes of prosecution systems are not equipped crime are more complex and criminals are accordingly. As the existing prosecution becoming more sophisticated. With the cannot render appropriate support to the increase of social sensitivity to crime, more law enforcing agencies in controlling and more a changing social attitude, crimes, the criminals are indulged and particularly towards the responsibility of consequently, crime trends increase in the citizenry to law enforcement, arises. society. Besides, due to insufficient Existing legal systems and preventative preventive intelligence, crime prevention, measures for controling crime have to be particularly preventive prosecution, does changed correspondingly. There should be not achieve much. an attempt to devise the ways and means to equip the older system of crime It has been noticed that the younger prevention and criminal justice to face generation in this part of the world is being these new challenges. -

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Bangladesh April 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.7 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 - 4.45 Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 1972 –1982 4.5 - 4.8 1983 – 1990 4.9 - 4.14 1991 – 1999 4.15 - 4.26 2000 – the present 4.27 - 4.45 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.51 The constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.13 Judiciary 5.14 - 5.21 Legal Rights /Detention 5.22 - 5.30 - Death Penalty 5.31 – 5.32 Internal Security 5.33 - 5.34 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.35 – 5.37 Military Service 5.38 Medical Services 5.39 - 5.45 Educational System 5.46 – 5.51 6. Human Rights 6.1- 6.107 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.53 Overview 6.1 - 6.5 Torture 6.6 - 6.7 Politically-motivated Detentions 6.8 - 6.9 Police and Army Accountability 6.10 - 6.13 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.14 – 6.23 Freedom of Religion 6.24 - 6.29 Hindus 6.30 – 6.35 Ahmadis 6.36 – 6.39 Christians 6.40 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.41 Employment Rights 6.42 - 6.47 People Trafficking 6.48 - 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 - 6.52 Authentication of Documents 6.53 6.B Human Rights – Specific Groups 6.54 – 6.85 Ethnic Groups Biharis 6.54 - 6.60 The Tribals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts 6.61 - 6.64 Rohingyas 6.65 – 6.66 Women 6.67 - 6.71 Rape 6.72 - 6.73 Acid Attacks 6.74 Children 6.75 - 6.80 - Child Care Arrangements 6.81 – 6.84 Homosexuals 6.85 Bangladesh April 2004 6.C Human Rights – Other Issues 6.86 – 6.89 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 6.86 - 6.89 Annex A: Chronology of Events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: References to Source Material Bangladesh April 2004 1. -

Mapping Exercise on Water- Logging in South West of Bangladesh

MAPPING EXERCISE ON WATER- LOGGING IN SOUTH WEST OF BANGLADESH DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS March 2015 I Preface This report presents the results of a study conducted in 2014 into the factors leading to water logging in the South West region of Bangladesh. It is intended to assist the relevant institutions of the Government of Bangladesh address the underlying causes of water logging. Ultimately, this will be for the benefit of local communities, and of local institutions, and will improve their resilience to the threat of recurring and/or long-lasting flooding. The study is intended not as an end point, but as a starting point for dialogue between the various stakeholders both within and outside government. Following release of this draft report, a number of consultations will be held organized both in Dhaka and in the South West by the study team, to help establish some form of consensus on possible ways forward, and get agreement on the actions needed, the resources required and who should be involved. The work was carried out by FAO as co-chair of the Bangladesh Food Security Cluster, and is also a contribution towards the Government’s Master Plan for the Agricultural development of the Southern Region of the country. This preliminary work was funded by DfID, in association with activities conducted by World Food Programme following the water logging which took place in Satkhira, Khulna and Jessore during late 2013. Mike Robson FAO Representative in Bangladesh II Mapping Exercise on Water Logging in Southwest Bangladesh Table of Contents Chapter Title Page no. -

Monthly Human Rights Observation Report on Bangladesh

Monthly Human Rights Observation Report on Bangladesh December, 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS SUPPORT SOCIETY (HRSS) www.hrssbd.org Monthly Human Rights Report –December, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMERY Human Right Support Society is published this report based on incidents of human rights violation and atrocities based on information received through our district representatives and based on twelve prominent national dailies, has published bimonthly Human Rights report. In Dec ’18, the freedom of expression was denied and the constitutionally guaranteed rights of freedom of assembly and association witnessed a sharp decline especially during the election campaign and the Election Day. Restrictions on the political parties and civil societies, impunity to the abusive security forces, extrajudicial killing, enforced disappearance, abduction, violence against women, indiscriminate arrest and assault on opposition political leaders and activists, coercion and extortion are exposed a very glooming scenario of the overall human rights situation in Bangladesh. The situation reached such awful state that even the common people feel insecure everywhere. According to the sources of HRSS, in December, at least 11 people were extra-judicially killed; a total of 25 people have been forcefully disappeared by the members of law enforcement agencies, later most of them shown arrest. Moreover, the HRSS report finds that, a total of 22 females have been raped. Of them, 07 were identified as an adult and alarmingly 15 were children under the age of 16. A total of 15 women were killed in the family feud, 03 females were killed due to dowry related violence. It has also been reported that a total of 23 were abducted in different areas of the country, among them approximately 10 were male, 03 females, 10 children, and 15 were killed after the abduction. -

Annex 13 Master Plan on Sswrd in Mymensingh District

ANNEX 13 MASTER PLAN ON SSWRD IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATIVES (MLGRD&C) LOCAL GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT (LGED) MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT NOVEMBER 2005 PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL (PCI), JAPAN JICA MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT Map of Mymensingh District Chapter 1 Outline of the Master Plan Study 1.1 Background ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.2 Objectives and Scope of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.3 The Study Area ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.4 Counterparts of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.5 Survey and Workshops conducted in the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 3 Chapter 2 Mymensingh District 2.1 General Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.2 Natural Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.3 Socio-economic Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.4 Agriculture in the District ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.5 Fisheries -

Dbœq‡Bi Myzš¿ ‡Kl Nvwmbvi Gj Gš

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Dbœq‡bi MYZš¿ Local Government Engineering Department ‡kL nvwmbvi g~jgš¿ Office of the Executive Engineer District: Sunamganj. www.lged.gov.bd e-Tender Notice Number : 38/2019-2020 Memo No. 46.02.9000.000.99.028.19 . 67 Date : 07/012020 e-Tender is invited in the e-GP Portal(http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the following Packages Tender ID Package No Name of work Date and time Date and time of No of last selling Closing Haor Infrastructure and Livelihood Improvement Project (HILIP) 408153 HILIP/19/WD3 Improvement of Teranagar-Fenarbak road at 06-Feb-2020 06-Feb-2020 /UNR- ch.3900-5363 & 5663-6509m under Jamalganj 12:00 14:00 SUN/Jam-01 Upazilla Dist-Sunamganj ID no-690503010 387635 CALIP/19/WD Village internal service of Borakhali Village under 19-Jan-2020 19-Jan-2020 2/VIS- Jagannathpur Upazila Dist.-Sunamganj. 12.00 14.00 SUN/Jag-10 W.W.E.L540m T.W 04T04 Construction of Under 100m Bridges on Upazila, Union & Village Road Project(CBU-100) 409089 CBU-100/ Construction of 54.00 m Long RCC Girder Bridge 06-Feb-2020 06-Feb-2020 Purto-124 on Gobindogonj GCM-Rasulganj GCM via Buraia 12:00 14:00 bazar Chhatak Part at ch.12930m [Road ID- 690232010]Upazilla Chatak DistSunamganj This is an online Tender, where only e-Tenders will be accepted in e-GP Portal and no offline/hard copies will be accepted. To submit e-Tender, please register on e-GP system (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for more details please contact support desk contact numbers. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Aamir, A. (2015a, June 27). Interview with Syed Fazl-e-Haider: Fully operational Gwadar Port under Chinese control upsets key regional players. The Balochistan Point. Accessed February 7, 2019, from http://thebalochistanpoint.com/interview-fully-operational-gwadar-port-under- chinese-control-upsets-key-regional-players/ Aamir, A. (2015b, February 7). Pak-China Economic Corridor. Pakistan Today. Aamir, A. (2017, December 31). The Baloch’s concerns. The News International. Aamir, A. (2018a, August 17). ISIS threatens China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. China-US Focus. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/isis-threatens- china-pakistan-economic-corridor Aamir, A. (2018b, July 25). Religious violence jeopardises China’s investment in Pakistan. Financial Times. Abbas, Z. (2000, November 17). Pakistan faces brain drain. BBC. Abbas, H. (2007, March 29). Transforming Pakistan’s frontier corps. Terrorism Monitor, 5(6). Abbas, H. (2011, February). Reforming Pakistan’s police and law enforcement infrastructure is it too flawed to fix? (USIP Special Report, No. 266). Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Abbas, N., & Rasmussen, S. E. (2017, November 27). Pakistani law minister quits after weeks of anti-blasphemy protests. The Guardian. Abbasi, N. M. (2009). The EU and Democracy building in Pakistan. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https:// www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democ racy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-29.pdf Abbasi, A. (2017, April 13). CPEC sect without project director, key specialists. The News International. Abbasi, S. K. (2018, May 24). -

HRSS Annual Bulletin 2018

Human Rights in Bangladesh Annual Bulletin 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS SUPPORT SOCIETY (HRSS) www.hrssbd.org Annual Human Rights Bulletin Bangladesh Situation 2018 HRSS Any materials published in this Bulletin May be reproduced with acknowledgment of HRSS. Published by Human Rights Support Society D-3, 3rd Floor, Nurjehan Tower 2nd Link Road, Banglamotor Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.hrssbd.org Cover & Graphics [email protected] Published in September 2019 Price: TK 300 US$ 20 ISSN-2413-5445 BOARD of EDITORS Advisor Barrister Shahjada Al Amin Kabir Md. Nur Khan Editor Nazmul Hasan Sub Editor Ijajul Islam Executive Editors Research & Publication Advocacy & Networking Md. Omar Farok Md. Imamul Hossain Monitoring & Documentation Investigation & Fact findings Aziz Aktar Md. Saiful Islam Ast. IT Officer Rizwanul Haq Acknowledgments e are glad to announce that HRSS is going to publish “Annual Human Rights Bulletin 2018”, focusing on Wsignificant human rights violations of Bangladesh. We hope that the contents of this report will help the people understand the overall human rights situation in the country. We further expect that both government and non-government stakeholders working for human rights would be acquainted with the updated human rights conditions and take necessary steps to stop repeated offences. On the other hand, in 2018, the constitutionally guaranteed rights of freedom of assembly and association witnessed a sharp decline by making digital security act-2018. Further, the overall human rights situation significantly deteriorated. Restrictions on the activities of political parties and civil societies, impunity to the excesses of the security forces, extrajudicial killing in the name of anti-drug campaign, enforced disappearance, violence against women, arbitrary arrests and assault on opposition political leaders and activists, intimidation and extortion are considered to be the main reasons for such a catastrophic state of affairs. -

Accord Final Report

The Bangladesh Accord Foundation has provided the information on this signatory supplier list as of 7th October 2013 “as is” without any representations or warranties, express or implied. Approximate Approximate Total number of Factories: Total number of 1557 workers: 2,025,897 Number of Number of separate Floors of the Number of Factory housing Factory housing workers Phone City Phone buildings Number of stories of each building which Active Account ID Factory Name Address District Division Postal Code Phone in multi‐purpose in multi‐factory employed by Code Extension belonging to building the factory Members in building building factory (all production occupies Factory buildings) facility 9758 4 Knitwear Ltd Pathantuli,Godnail Narayanganj Dhaka 1400 2 7641780 No No 450 1 9965 4 You Clothing Ltd 367/1 Senpara parbota Mirpur Dhaka Dhaka Dhaka 1216 2 8020125 1/10; No No 2000 1 9552 4A YARN DYEING LTD. Kaichabari, Savar Dhaka Dhaka 2 79111568 3 1/5; 2/1; 3/1; No No 1250 3 10650 4S Park Style Ltd Durgapur, Ashulia, Savar. Dhaka Dhaka Dhaka 1341 2 9016954 1 6 no No 1/10 1200 1 10562 A Class Composite Ltd. East Isdair, Beside LGED Office, Fatullah, Narayanganj Dhaka 2 7642798 No No 1 Narayanganj 10086 A J Super Garments Ltd. Goshbag, Post‐ Zirabo, Thana ‐ Savar Dhaka Dhaka 1341 2 7702200 1 1/6; No No 2700 1 10905 A Plus Ind.Ltd. Plot‐28, Milk Vita Rd., Section‐07, Mirpur, Dhaka Dhaka Dhaka 1216 2 9338091 1 1/6; No Yes 1/0,3,4,5; 2200 1 10840 A&A Trousers Ltd Haribari Tak, Pubail Collage Gate, Pubail, Gazipur Dhaka 2 224255 1 1/5; Yes Yes 1/5‐2/5; 1200 1 Gazipur, Sadar, Gazipur 9229 A&B Outerwear Ltd Plot #29‐32, Sector # 4, CEPZ, Chittagong.