Frances Willard's Pedagogical Ministry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940)

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940) Nursing is love in action, and there is no finer manifestation of it than the care of the poor and disabled in their own homes Lillian D. Wald was a nurse, social worker, public health official, teacher, author, editor, publisher, women's rights activist, and the founder of American community nursing. Her unselfish devotion to humanity is recognized around the world and her visionary programs have been widely copied everywhere. She was born on March 10, 1867, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of four children born to Max and Minnie Schwartz Wald. The family moved to Rochester, New York, and Wald received her education in private schools there. Her grandparents on both sides were Jewish scholars and rabbis; one of them, grandfather Schwartz, lived with the family for several years and had a great influence on young Lillian. She was a bright student, completing high school when she was only 15. Wald decided to travel, and for six years she toured the globe and during this time she worked briefly as a newspaper reporter. In 1889, she met a young nurse who impressed Wald so much that she decided to study nursing at New York City Hospital. She graduated and, at the age of 22, entered Women's Medical College studying to become a doctor. At the same time, she volunteered to provide nursing services to the immigrants and the poor living on New York's Lower East Side. Visiting pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled in their homes, Wald came to the conclusion that there was a crisis in need of immediate redress. -

Hlocation of Legal Description

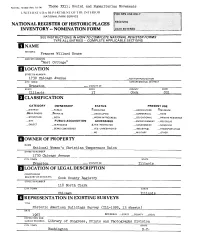

Form NO 10-300 (Rev 10-74) Theme XXI1; Social and Humanitarian Movements UNIT ED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Frances Willard House AND/OR COMMON "Rest Cottage" (LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Evans ton — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 17 Cook 031 HfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) J<PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -..COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER QJOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME National Woman's Christian Temperance Union STREET & NUMBER 1730 Chicago Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Evanston — VICINITY OF Illinois HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Cook County Registry STREET& NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY, TOWN STATE Ct|icaeo Illinois 3 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (ILL-1095, 13 sheets) DATE 1967 XFEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division " ~ " —--——————————————— CITY, TOWN Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE JfEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^-UNALTERED X—ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The home of Frances Willard and her family and the longtime headquarters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union was built by her father, Josiah Willard in 1865 and added to in 1878. -

HISTORY 263: U.S. Women's History

HISTORY 263: U.S. Women’s History This is a preliminary syllabus ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Summer 2012 HISTORY 263: U.S. Women’s History Instructor: Dr. Mara Dodge Tel. 413-572-5620 Use PLATO e-mail only Office: Bates 104 Course Description: This course explores all of American women’s history from the colonial period to the present and is open to students from any major. However, there is a daunting amount of material to cover in just 6 weeks so be prepared for a heavy reading load and a fast pace (and remember it is a 200 level course!) The course provides an excellent overview/ review of all of U.S. history with a special emphasis on women’s experiences and contributions. The course emphasizes the diversity of women’s experiences. We explore the unique experiences of specific European ethnic/ immigrant groups (ex. Irish, Italian, etc.) as well as the experiences of African-American, Native American, Asian-American, Latina, Jewish, Muslim, and lesbian women. The course makes extensive use of primary source materials. 1 Major themes include: changing ideas about women’s “proper place” in society; the history of the women’s rights movement; women’s role in social reform; changing ideas about sexuality, family, and reproduction; images of beauty and the “feminine ideal”; women and work; and movements for civil and legal rights. Note: Westfield State University assumes that a student will need to spend 16-20 hours a week to complete a 3 credit, on-line course in 6 weeks. These hours include all weekly course work and may include such activities as: textbook readings and assignments, watching videos, viewing Powerpoints, listening to podcasts, taking quizzes and exams, conducting research, writing essays/papers, posting to class discussion boards, and completing any other assigned weekly activities. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9001986 The mission of women’s colleges in an era of cultural revolution, 1890-1930 Leone, Janice Marie, Ph.D. -

FALCON V, LLC, Et Al.,1 DEBTORS. CASE NO. 19-10547 CHAPT

Case 19-10547 Doc 103 Filed 05/21/19 Entered 05/21/19 08:56:32 Page 1 of 13 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: CASE NO. 19-10547 FALCON V, L.L.C., et al.,1 CHAPTER 11 DEBTORS. (JOINTLY ADMINISTERED) ORDER APPROVING FALCON V, L.L.C.'S ACQUISITION OF ANADARKO E&P ONSHORE LLC’S INTEREST IN CERTAIN OIL, GAS AND MINERAL INTERESTS Considering the motion of the debtors-in-possession, Falcon V, L.L.C., (“Falcon”) for an order authorizing Falcon’s acquisition of the interest of Anadarko E&P Onshore LLC (“Anadarko”) in certain oil, gas and mineral leases (P-13), the evidence admitted and argument of counsel at a May 14, 2019 hearing, the record of the case and applicable law, IT IS ORDERED that the Debtors are authorized to take all actions necessary to consummate the March 1, 2019 Partial Assignment of Oil, Gas and Mineral Leases (the “Assignment”) by which Anadarko agreed to assign its right, title and interest in and to certain oil, gas and mineral leases in the Port Hudson Field, including the Letter Agreement between Falcon and Anadarko attached to this order as Exhibit 1. IT IS FURTHERED ORDERED that notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this order, the relief granted in this order and any payment to be made hereunder shall be subject to the terms of this court's orders authorizing debtor-in-possession financing and/or granting the use of cash collateral in these chapter 11 cases (including with respect to any budgets governing or related to such use), and the terms of such financing and/or cash collateral orders shall control if 1 The Debtors and the last four digits of their respective taxpayer identification numbers are Falcon V, L.L.C. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

Copyright (C) 2005 Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Massachusetts Permission to Publish from This Material Should Be Discussed with the Museum Curator

Guide to the Transcendentalist Manuscript Collection, Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Massachusetts www.fruitlands.org REGISTER MS T.1 S. Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810-1850) Papers, ca 1836-1850 Size: 2 Linear inches Acquisition: Materials were purchased from The Goodspeed Book Shop by Clara Endicott Sears BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH S. Margaret Fuller Ossoli (May 23, 1810-July 19, 1850) was a well known author, lecturer, and Transcendentalist in the Nineteenth Century. She is often called a "bluestocking", because of her feminist beliefs and unconventional life. She was born Sarah Margaret Fuller, the first of nine children of Timothy and Margaret Fuller of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. Her father was determined to give her a masculine education according to the classical curriculum of the day. The exacting and regimental education began at a very young age and was to take a great toll on her health. But it also gave her abroad knowledge of literature and languages. Following the completion of her formal studies, Margaret gained entrance into the intellectual circles of Cambridge and Harvard. Here she formed lasting friendships with many New England intellectuals. In 1836, Margaret Fuller was hired to teach languages at Bronson Alcott's Temple School. She stayed only a year, but continued her teaching career in Providence Rhode Island at the Greene Street School. In 1839, she returned to Massachusetts and began conducting "Conversations" for society women and others in Boston. At this time, Margaret Fuller also became an integral part of the Transcendentalist Movement. From 1840 to 1842 she edited and contributed to the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial. In 1845, she published her feminist work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. -

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY a Long March for Suffrage

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge in1810. By her late teens, she was considered a prodigy and equal or superior in intelligence to her male friends. As an adult she hosted “Conversations” for men and women on topics that ranged from women’s rights to philosophy. She joined Ralph Waldo Emerson in editing and writing for the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial from 1840-1842. It was in this publication that she wrote an article about women’s rights titled, “The Great Lawsuit,” which she would go on to expand into a book a few years later. In 1844, she moved to NYC to write for the New York Tribune. Her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in1845. She traveled to Europe as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent, the first woman to hold such a role. She died in a shipwreck off the coast of NY in July 1850 just as she was returning to life in the U.S. Her husband and infant also perished. It was hoped that she would be a leader in the equal rights and suffrage movements but her life was tragically cut short. 02 SARAH BURKS, CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL COMMISSION December 2019 CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Harriet A. Jacobs (1813-1897) was born into slavery in Edenton, NC. She escaped her sexually abusive owner in 1835 and lived in hiding for seven years. In 1842 she escaped to the north. She eventually was able to secure freedom for her children and herself. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

T H E C O Rin Th Ia N

May 2020 Volume 41, Issue 5 Strawberry Festival Canceled We are sorry to announce that the 46th annual Greece Historical Society Strawberry and Dessert Tasting Festival, scheduled for June 22nd, is canceled. The GHS Board of Trus- tees made the difficult decision to cancel our 2020 Festival due to the COVID-19 global pandemic We held off announcing the cancellation in hopes that the COVID pandemic would be resolved in time to still have our June 22nd festival, but it is now clear that won't happen We would like to thank all our vendors, event sponsors, community groups, members and friends, and especially our volunteers who have made our past festivals possible. While we are all deeply disappointed that this year’s event will not take place, we do plan to continue the tradition in 2021 and possibly have a different community event later this year. Membership Renewal May 1st through April 30th is the membership year in the Greece Historical Society. We sent a reminder letter to our current members early last month and are encouraged at the number of people who have renewed. If you are not a member please consider supporting the Greece Historical Society with a paid membership. Your membership will help support the programs and exhibits of the Society & Museum and the maintenance of our building, plus you will receive our monthly newsletter, the "Corinthian" . Membership applications are available at our museum and on our website at http:// greecehistoricalsociety.org/join-us/membership/. The Greece Historical Society is supported solely by the community and receives no fi- nancial assistance from local government. -

Semifinalists: 2021 National Merit Scholarship Program

160 Rich, Samantha M. CLIFTON PARK Semifinalists: 2021 National 821 Santora, Jeremy J. SHENENDEHOWA H. S. 999 Tunnicliffe, Galen 302 Grady-Willis, Emi A. Merit Scholarship Program 162 Wong, Emily 200 Han, Alice 742 Huang, Yicheng PACKER COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE 906 Kelly, Jack 821 Baum, Eli C. 000 Mackey, Catherine F. 000 Craig-Schwartz, Jordyn S. 600 Park, Brian 000 Harrell, Harper C. 000 Stevens, Taina 000 Paredes, Jaymie 000 Levine, Samuel O. 303 Tang, Kah Shiuh NEW YORK 000 Polish, Isadora J. 000 Yohn, Nicholas V. 450 Yevzerov, Alexander M. 000 Promi, Ramisa ALBANY 000 Reynolds, Kate POLY PREP COUNTRY COLD SPRING 000 Schrader, Max A. ACADEMY OF THE HOLY NAMES DAY SCHOOL HALDANE H. S. 000 Schwarz, Aviva 454 Bell, Megan E. 161 Axinn, Isadore J. 720 Kottman, Sophia O. 000 Sison, Benjamin E. 000 Morris, Henry J. 000 Sze, Edgar 000 Purohit, Gauri A. ALBANY ACADEMIES 000 Van Deventer, Hugh F. COLD SPRING HARBOR 455 Alonge, Mia C. 000 Yamaguchi, Jason A. COLD SPRING HARBOR H. S. 999 ST. ANN'S SCHOOL Li, Alex S. 000 Yamner, Miles E. 454 Ross, Matthew F. 712 302 Mody, Kiran S. Madan, Jay M. 000 Zeana-Schliep, Lars 943 Schisgall, Elias J. COMMACK 843 Tom, William J. AMHERST FIELDSTON SCHOOL COMMACK H. S. AMHERST CENTRAL H. S. 000 Hendrickson, Rachel A. 000 Chen, Kevin 628 Kang, Alex 000 Johnson, Julie A. BUFFALO 555 Park, Paul J. BUFFALO ACADEMY OF THE 450 Whitton, Max M. 000 Kao, Denika 999 Tawadros, Catherine A. SACRED HEART 999 Kim-Suzuki, Saya S. 000 Walsh, Jordan M. -

A Female Factor April 12, 2021

William Reese Company AMERICANA • RARE BOOKS • LITERATURE AMERICAN ART • PHOTOGRAPHY ______________________________ 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06511 (203) 789-8081 FAX (203) 865-7653 [email protected] A Female Factor April 12, 2021 Celebrating a Pioneering Day Care Program for Children of Color 1. [African Americana]: [Miller Day Nursery and Home]: MILLER DAY NURSERY AND HOME...THIRTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY PROGRAM... EBENEZER BAPTIST CHURCH [wrapper title]. [Portsmouth, Va. 1945]. [4]pp. plus text on inner front wrapper and both sides of rear wrapper. Quarto. Original printed wrappers, stapled. Minor edge wear, text a bit tanned. Very good. An apparently unrecorded program of activities planned to celebrate the thirty- fifth anniversary of the founding of the Miller Day Nursery and Home, the first day care center for children of color in Portsmouth, Virginia. The center and school were established by Ida Barbour, the first African-American woman to establish such a school in Portsmouth. It is still in operation today, and is now known as the Ida Barbour Early Learning Center. The celebration, which took place on November 11, 1945, included music, devotionals, a history of the center, collection of donations, prayers, and speeches. The work is also supplemented with advertisements for local businesses on the remaining three pages and the inside rear cover of the wrappers. In all, these advertisements cover over forty local businesses, the majority of which were likely African-American-owned es- tablishments. No copies in OCLC. $400. Early American Sex Manual 2. Aristotle [pseudonym]: THE WORKS OF ARISTOTLE, THE FAMOUS PHILOSOPHER. IN FOUR PARTS. CONTAINING I.