Eleven Seconds Underwater Matthew .W Vadnais Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

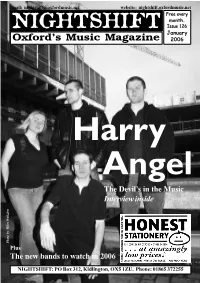

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 126 January Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Harry Angel The Devil’s in the Music Interview inside Photo by Miles Walkden Photo by Miles Plus The new bands to watch in 2006 NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 Evenings and Boywithatoy are among the local NEWNEWSS artists remixing the band. PINDROP PERFORMANCES is a new Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU monthly live music club night launched this Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] month at The Port Mahon in St Clement’s. Pindrop aims to showcase the best up and coming alternative folk and electronic acts THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT will take while the ground floor venue frontage will around. The first night takes place on Sunday place on Wednesday 10th May. Arrangements include a new bar area. A timetable for the 29th January and features Brickwork Lizards, for the annual showcase of the best unsigned refurbishment is yet to be finalised; in the The Thumb Quintet and Dan Glazebrook and music in Oxfordshire, organised by Nightshift, meantime the Zodiac is booking its spring Josie Webber. Each event starts at 5pm and are almost complete, with five venues already programme. Notable gigs already confirmed finishes at 8pm and tickets are limited to 35. confirmed and two more to be confirmed. As include: The Kooks (10th February), Julian Get them from Polar Bear on Cowley Road. ever, the Punt will kick off at Borders in Cope (14th Feb), The Paddingtons (16th Feb), Magdalen Street before moving on to Jongleurs, Regina Spektor (16th Feb), Battle (4th March), OXFORDBANDS.COM has launched an The Wheatsheaf, The City Tavern and finishing The Buzzcocks (5th Mar), Cave In (6th Mar), 65 updated version of its interactive venue guide. -

Cash Box: Album Reviews Pop Picks

cash box: album reviews pop picks COME ON OVER - Olivia Newton -John - MCA SONG OF JOY - Captain & Tennille - A&M SP 2186 - Producer: John Farrar - List: 6.98 4570 - Producers: Captain & Tennille - List: The constantly maturing vocals of Olivia ((//WJJ^^''// 6.98 Newton -John continue their musical growth on "Song Of Joy" by the Captain & Tennille is "Come On Over." Ms. Newton -John puts effec- characterized by a clear and entertaining bal- tive emotion into every song and, when played ance of music. Soulful ballads as well as uptem- off against clear instrumentals, strikes an effec- po movers benefit equally from Toni Tennille's tive tone on ballad and uptempo numbers alike. vocals and an overall clear production. Of AM adds are a cinch while easy listening and particular note this outing is the depth of each middle of the road lists should do the same. Top piece of music. Hats off to arrangement. AM cuts include "Who Are You Now?" "Blue Eyes chances are assured while easy listening outlets Crying In The Rain" and a moving cover of will also be there. Top cuts include "Smile For "Jolene." Me One More Time," "Thank You Baby" and a rousing cover of "Shop Around." ROCH N' ROLL ROCK 'N' ROLL LOVE LETTER - Bay City VE LETTER A TRICK OF THE TAIL - Genesis - Atco SD Rollers - Arista AL 4071 - Producers: Phil 36129 - Producers: David Hentschel and Gen- Wainman and Colin Frechter - List: 6.98 esis - List: 6.98 On "Rock 'N' Roll Love Letter" the Bay City Musical references and influences prove en- Rollers prove skilled practitioners of the pop and tertaining and recognizable on "A Trick Of The rock arts. -

George Harrison Visit 12/13/74” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 40, folder “Ford, John - Events - George Harrison Visit 12/13/74” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 40 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ROGERS & COWAN1 INC. 598 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK, N. Y. 10022 PUBLIC RELATIONS (212) 759-6272 CABLE ADDRESS ROCOPUB NEW YORK ,NEW YORK December 20, 1974 Ms. Sheila Widenfeld East Wing Press Off ice The White House Washington, D.c. 20500 Dear Sheila: Once again I extend many thanks for your assistance regarding George Harrison's visit to the White House. It was a superb day. Best regards, terling ._.."l.r..,...,...iainment Division , MS/aes 250 NORTH CANON DRIVE, BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA 90210 CRESTVIEW 5-4581 CABLE ADDRESS: ROCOPUB BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA -- I . -

TIGERSHARK Magazine

TIGERSHARK magazine Issue Fifteen – Autumn 2017 – Different Lives Tigershark Magazine Contents Fiction Issue Fifteen – Autumn 2017 Boring Vacation Different Lives Denny E. Marshall 3 A Snapshot of Society Mark Hudson 4 Editorial The Conversation Everyone is different, but we don’t always see that much DJ Tyrer 5 diversity in print. The aim of this issue – perhaps not quite as successful as it might have been – is to include pieces Dives from around the world revealing different lives. I think you Christopher Woods 10 will be entertained and informed. I may try a similar Kingston, London theme next year (I haven’t finalised on any yet, so, if you have a suggestion, drop me an email), but would also like Nick Piat 12 to remind all potential contributors that I’m always Dark Side of the Moon interested in receiving submissions from anyone Craig Smith 18 anywhere in the world and featuring all sorts of characters, cultures and locations, regardless of the topic, The Ghosts of Ourselves and am always happy to consider unthemed work. So, if Colin Farrington 25 you have a story, poem or article, don’t worry if we Bars haven’t featured anything like it before, send it along. Tony Concannon 29 Contributors are invited to submit a bio for inclusion on the Tigershark website and your comments on the issue The Bargain are welcome. Bill Davidson 36 Best, DS Davidson He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Concrete Buddha Neil K. Henderson 48 © Tigershark Publishing 2017 All rights reserved. Moloch Isn’t Eating Authors retain the rights to their individual work. -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking -

Søren Noah׳S Musiksamling 1. Juli 2011

SSøørreenn NNooaahh’’ss mmuussiikkssaammlliinngg 11.. jjuullii 22001111 Kunstner Album-titel # Format Årstal Genre Abba Abba Gold 134 CD 1992 Pop Afro Cuban All Stars Distinto, diferente 74 CD 1999 Salsa Airto Moireira Touching you touching me 130,2 Cass 1979 Latinjazz Al Di Meola Elegant gypsy 19 LP 1977 Fusion Al Jarreau Best of 376 CD 1996 Pop Al Jarreau L is for Lover 265,1 Cass 1986 Pop Al Jarreau Jarreau 92 LP 1983 Pop Al Jarreau & George Benson Givin' it up 380 CD 2006 Pop Alexander Vaulin (piano) Scandinavian romantic piano musik (vol. 2) 402 CD 2004 Klassisk Alphonso Johnson Yesterday's dreams 100 LP 1976 Fusion Ana Laura & Fernando Show Tango Argentino Vol. 2 246 CD 2003 Tango Andrea Bocelli Cieli di Toscana 458 CD 2001 Klassisk Andrés Segovia Dedication (2 cd) 401 CD 2004 Klassisk Andrew Lloyd Webber Highlights from ... "Phantom of the opera" 173 CD 1987 Musical Andrew Strong Out of time 88 CD 2000 Rock Angela Hewitt Chopin Nocturnes 327 CD 2004 Klassisk Anima Live Musikcafeen 1982 (bootleg fra DR) 188 CD 1982 Fusion Anima Kilgore 276 CD 1980 Fusion Anima Kilgore 66 LP 1980 Fusion Anne Dorte Michelsen Mellem dig og mig 316,1 Cass 1983 Pop Anne Linnet Nattog til Venus (2 CD) 494 CD 1999 Pop Anne Linnet Jeg er jo lige her 329,1 Cass 1988 Dansk Anne Linnet Hvid magi 107 LP 1985 Dansk Anne Linnet You´re crazy 55 LP 1979 Dansk Aretha Franklin Through the storm 176 LP 1989 Pop Aske Bentzon Badminton 24 LP 1979 Dansk Astor Piazzolla Chamber works 354 CD 2001 Tango Astor Piazzolla Classic tracks from Argentina 155 CD 1993 Klassisk Astor Piazzolla Key works 1984-1989 379 CD Tango Astor Piazzolla & Kronos Quartet Five tango sensations 156 CD 1991 Klassisk Bach m.fl. -

April 6 1976 CSUSB

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Paw Print (1966-1983) CSUSB Archives 4-6-1976 April 6 1976 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint Recommended Citation CSUSB, "April 6 1976" (1976). Paw Print (1966-1983). Paper 202. http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint/202 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CSUSB Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paw Print (1966-1983) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reporters & Writers Urgently Needed., page 2 Pleas? return to Offict. of r-jbiictifion Caiiiornio Stafo Colleg Gov. Brown Appoints SFSU San Bernardirio Woman To Trustee Position page 3 Jirrklg Pauijprtnt Published by the Associated Students of Cal-State, San Bernardino Tuesday, April 6,1976 Prickly Peor Seeks Contributions . page 5 What's Rock & Roll got to do with Finland.. page 8 Child Core Center Finally Opens . page 9 Corol Goss, Col-Stole Politicol Science instructor, registers people to vote during m her reguior office hours. Photo by Keith Legerat The Weekly PawPrint, Tuesday, April 6,1976, page 2 Writers and others needed By John Whitehair We need help. Just like at the beginning of every other quarter, we are making an appeal for students to get involved with their campus newspaper. Writing articles for a college newspaper gives a student an excellent chance to get some experience that cannot be gained in the classrooms. Most employers always ask perspective employees if they have been involved in any extra-curricular activities. -

Cash Box, News

cash box, news POINTS WEST - "Are you ready for this? I have absolutely no background in the rec- Atlantic Release Features ord business at all." While that probably measures out an accurate description of many of us involved in this industry. you've got to admit it's a pretty candid opener. Hal Freeman of Cin-Kay Records - "An Independent By Choice" - however. is Zeppelin, Wyman, Genesis flushed with victory at the moment. so he can be excused. And if you don't care to ex- cuse him. it won't matter much. because he's a very determined man. Two of his first NEW YORK Atlantic/Atco Records positions previously unavailable in the - three releases have broken onto the Cash Box country singles chart this week in the latest album release is led by 4 -channel mode for which they were in- forms of "Love Isn't Love (Till You Give It Away)" In "Presence," the seventh album by Led tended. by Eddie Bailes and Al Bolt's "I'm Love With My Pet Rock." Zeppelin (on Swan Song Records). Merchandising information, publicity Freeman is one of those characters who either acts on an idea immediately or lets it "Stone Alone." the second solo album materials and promotion priorities have ride completely. There's no in-between. Both earnest and easy-going. Hal scrapes from Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones been circulated in advance to all WEA the floor with the voice a radio (via Rolling Stone Records), and "A Corp. sales managers. marketing of jock as he speaks: "I'd been wondering why no one had released a record on a pet rock. -

Issue 133.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 133 August Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 The Half Rabbits Welcome to the dark side - interview inside plus TRUCK FESTIVAL Four-page review inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 DR SHOTOVER NEWNEWSS A Cornball In Cornwall Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU I say, did you see Shack at the Zodiac the other month? Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Much West Coast 60s melodicism and top-quality harmony vocals... so inspired was I by their song ‘Cornish Town’ that I found myself heading to the THIS YEAR’S WITTSTOCK (South) West Coast for my last golfing holiday... a FESTIVAL takes place over the weekend splendid little place in the Duchy of Cornwall called (I kid you not) Rock. Apparently it’s twinned with a small of 18th – 20th August. The three-day French town called Role... but I digress. I played a hole or festival is free and features a wide two, then, having pushed some Young People over a cliff selection of local bands and singers and for wearing aims to raise money for Motor Neurone offensive Disease research through donations and wetsuits, I sales of programmes and raffle tickets. settled in at the Headline act on the Friday night are club bar and hardcore punk wackos Barry & The regaled the Beachcombers; Saturday’s main acts locals with a few include Mary’s Garden, Junkie Brush, choice stories Phyal, Smilex and Twizz Twangle, while about my Burma on Sunday Suitable Case For Treatment days. -

Steve Gibbons Band „Live at Rockpalast “

Steve Gibbons Band „Live At Rockpalast “ Elisabeth Richter Hildesheimer Straße 83 30169 Hannover GERMANY Tel.: 0049‐511‐806916‐16 VÖ: 25.03.2011 Fax: 0049‐511‐806916‐29 CD Cat. No.: MIG 90342 Cell: 0049‐177‐7218403 Format: 1CD elisabeth.richter@mig‐music.de Genre: Rock WHEN HE STROLLED TO THE STAGE IN THE PALATIAL SURROUNDINGS OF THE BERLIN METROPOL STEVE GIBBONS WAS CERTAINLY NO NEWCOMER. HE HAD BEEN TO GERMANY SEVERAL TIMES BEFORE, THE FIRST TIME BEING 1963 WHEN HE AND HIS FELLOW BAND MEMBERS IN THE UGLYS GAVE UP THEIR DAY JOBS AND ACCEPTED THE OFFER OF A SIX WEEK ENGAGEMENT AT THE 'KON TIKI CLUB' IN MUNSTER WESTFALIA. ALTHOUGH THEY NOW HAD THE GREAT LUXURY OF NOT HAVING TO GET UP EARLY EVERY DAY IT WAS STILL HARD WORK, STARTING AT 9PM AND PLAYING THREE OR FOUR LONG SETS TILL THE EARLY HOURS OF THE MORN. THE MUSIC WAS ESSENTIALLY ROCK N ROLL, ELVIS, JERRY LEE, CHUCK BERRY, BUDDY HOLLY, GENE VINCENT, EDDIE COCHRAN AND ALSO LONNIE DONEGAN, THE KING OF SKIFFLE, BUT STEVE WAS SOON TO HEAR SOMETHING THAT WOULD COMPLETELY CHANGE HIS MUSICAL VISION. ONE NIGHT THE AMERICAN HOUSE DISC JOCKEY PUT THE NEEDLE DOWN ON A BRAND NEW RELEASE 'THE FREEWHEELIN BOB DYLAN' AND STEVE WAS DUMBFOUNDED. THE PROFOUND INFLUENCE THAT DYLAN’S MUSIC HAS HAD ON HIM OVER THE YEARS CAN BE HEARD NOT ONLY IN HIS SINGING TECHNIQUE --- GIBBONS IS STILL TODAY REGARDED AS ONE OF THE BEST 'INTERPRETERS OF DYLAN' BY MANY CRITICS --- BUT ALSO IN THE LYRICS OF THE SONGS HE WROTE WHICH BECAME INCREASINGLY SOCIALLY AWARE AND EVEN PSYCHODELIC. -

April 6 1976

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Paw Print (1966-1983) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 4-6-1976 April 6 1976 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint Recommended Citation CSUSB, "April 6 1976" (1976). Paw Print (1966-1983). 202. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint/202 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paw Print (1966-1983) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reporters & Writers Urgently Needed., page 2 Pleas? return to Offict. of r-jbiictifion Caiiiornio Stafo Colleg Gov. Brown Appoints SFSU San Bernardirio Woman To Trustee Position page 3 Jirrklg Pauijprtnt Published by the Associated Students of Cal-State, San Bernardino Tuesday, April 6,1976 Prickly Peor Seeks Contributions . page 5 What's Rock & Roll got to do with Finland.. page 8 Child Core Center Finally Opens . page 9 Corol Goss, Col-Stole Politicol Science instructor, registers people to vote during m her reguior office hours. Photo by Keith Legerat The Weekly PawPrint, Tuesday, April 6,1976, page 2 Writers and others needed By John Whitehair We need help. Just like at the beginning of every other quarter, we are making an appeal for students to get involved with their campus newspaper. Writing articles for a college newspaper gives a student an excellent chance to get some experience that cannot be gained in the classrooms. Most employers always ask perspective employees if they have been involved in any extra-curricular activities. -

Private Diary of James Wickersham July 6, 1927 to Oct 1, 1928 Sister

Alaska State Library – Historical Collections Diary of James Wickersham MS 107 BOX 6 DIARY 38 July 6, 1927 through October 1, 1928 Diary 38, 1927- [Front cover] Judge Reed on former case, so not argued. 1928 Private Diary Hellenthal, appearing for Treas. would not argue of question, but Rustgard, Atty Genl. did so, briefly, James Wickersham without the authorities. At Judge Reeds request I July 6, 1927 to Oct 1, 1928 presented the law on the point of the Parties: Hellenthal then talked - but I think the court will Sister Jen’s sickness & death pp. Aug 9th to April 6 sustain him on the point of the right of the taxpayer pp 27-55. & the defendant on the other questions: Then I will Dr. S. Hall Young’s death p.55 appeal. Geo. F. Reids death p. 130. Leave for Skagway tonight on “Alameda,” and will return on same next Monday. Diary 38, 1927 July 6th 1927. Diary 38, 1927 -10th - July 6-8 Busy in office as usual. Have a bad cold - but July 10 SS. Alameda docked at Haines at Six a.m. Met recovering. Mrs. Snyder on dock and talked with her about trial -7th – of her divorce case. Promised to see Bruce Brown Same as usual. Busy in office. & see if he is competent to be a witness for her & Mike Sullivan from Yakataga Oil fields in office. notify her. The German cruiser lying in the stream Preparing copies reports of Experts who have off Haines. examined that field to send with letter to J.B.