TIGERSHARK Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019

Saturday 18th May 2019 | 10:00 Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019 Lot 19 Description Estimate 5 x Doo Wop / RnB / Pop 7" singles. The Temptations - Someday (Goldisc £15.00 - £25.00 3001). The Righteous Brothers - Along Came Jones (Verve VK-10479). The Jesters - Please Let Me Love You (Winley 221). Wayne Cochran - The Coo (Scottie 1303). Neil Sedaka - Ring A Rockin' (Guyden 2004) Lot 93 Description Estimate 10 x 1980s LPs to include Blondie (2) Parallel Lines, Eat To The Beat. £20.00 - £40.00 Ultravox (2) Vienna, Rage In Eden (with poster). The Pretenders - 2. Men At Work - Business As Usual. Spandau Ballet (2) Journeys To Glory, True. Lot 94 Description Estimate 5 x Rock n Roll 7" singles. Eddie Cochran (2) Three Steps To Heaven £15.00 - £25.00 (London American Recordings 45-HLG 9115), Sittin' On The Balcony (Liberty F55056). Jerry Lee Lewis - Teenage Letter (Sun 384). Larry Williams - Slow Down (Speciality 626). Larry Williams - Bony Moronie (Speciality 615) Lot 95 Description Estimate 10 x 1960s Mod / Soul 7" Singles to include Simon Scott With The LeRoys, £15.00 - £25.00 Bobby Lewis, Shirley Ellis, Bern Elliot & The Fenmen, Millie, Wilson Picket, Phil Upchurch Combo, The Rondels, Roy Head, Tommy James & The Shondells, Lot 96 Description Estimate 2 x Crass LPs - Yes Sir, I Will (Crass 121984-2). Bullshit Detector (Crass £20.00 - £40.00 421984/4) Lot 97 Description Estimate 3 x Mixed Punk LPs - Culture Shock - All The Time (Bluurg fish 23). £10.00 - £20.00 Conflict - Increase The Pressure (LP Mort 6). Tom Robinson Band - Power In The Darkness, with stencil (EMI) Lot 98 Description Estimate 3 x Sub Humanz LPs - The Day The Country Died (Bluurg XLP1). -

What's It Like to Be Black and Irish?

“What’s it like to be black and Irish?” “Like a pint of Guinness.” The above quote is taken from an interview with Phil Lynott, the charismatic lead singer of the Celtic rock band Thin Lizzy, on Gay Byrne’s ‘The Late Late Show’. Lynott’s often playful and bold responses to such questions about his identity served to mask his overwhelming feelings of insecurity and ambivalent sense of belonging. As an illegitimate black child brought up in the 1950s in a strict Catholic family in Crumlin, a working-class district of Dublin, Lynott was seen to have a “paradoxical personality” (Bridgeman, qtd. in Thomson 4): his upbringing imbued him “with an acute sense of national and gender identity” (Smyth 39), yet his skin color and illegitimacy made him the target of racial and social abuse in a predominantly white and conservative Ireland. For Lynott, becoming a rockstar offered an opportunity to reinvent himself and be whoever he wanted to be. While he played up to the rock and roll lifestyle in which he was embedded, Lynott is often considered to have been a man trapped inside a caricature (Thomson 301). Geldof (qtd. in Putterford 182) believes that this rocker persona was Lynott’s ultimate downfall and led to his untimely death at just 36 years of age in 1986. For all his swagger and bravado, behind the mask, Lynott was a troubled, young man searching for a place to belong. While many books have been written about the life of Phil Lynott (e.g. Putterford; Lynott; Thomson), few have drawn attention to the notion of identity and the way in which music provided Lynott with an outlet to explore his self. -

Adams Changes with Students by LYN M

Adams changes with students By LYN M. MUNLEY Student priorities are "The students today seem respect for grades — more the jobs are there on a changing, and the man at the to be a more mature group concern about career devel- qualitative basis, and the "heart of the institution," than I've ever seen," Adams opment and placement. Stu- competition is rough," he Frederick G. Adams, is pick- claims, "We don't have the dents seem to be aware of says. ing up the beat. emotional kinds of issues the economic realities of the Another kind of competi- As vice president for that drain our productive country," Adams says. tion, involving student gov- student affairs and services, energies. We can facilitate "People are more concern- ernment officials, worries Adams has his finger on the the learning of the three r's ed about themselves as indi- Adams. "There's a real pulse of the ujniversity. He is much more easily this way.' viduals. Even in dancing problem with the number of in charge of the human After being at UConn for closer together the concern is working hours the officials aspect of UConn's produc- nearly 10 years, first as reflected. It's healthy," he must expend vis a vis com- tion of educated beings. ombudsman, then in the remarks. peting priorities, such as As an individual, Adams school of allied health, then Adams points to what he their academic studies. I exudes an air of idealism, into administrative duty in 60's has turned into the calls a "competitive renais- wish there were some way to optimism and total involve- 1974, Adams has certainly silence of the 70's. -

Eleven Seconds Underwater Matthew .W Vadnais Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1999 Eleven seconds underwater Matthew .W Vadnais Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Vadnais, Matthew W., "Eleven seconds underwater" (1999). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 177. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/177 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eleven seconds underwater by Matthew William Vadnais A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Barbara Haas Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1999 Copyright© Matthew William Vadnais, 1999. All rights reserved 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's Thesis of Matthew William Vadnais has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signature redacted for privacy Major Professor Signature redacted for privacy For the Major Program Signature redacted for privacy For the Graduate College iii For my parents for knowing how to let go. For Allen Blair, Joshua Vadnais, and Patrick Wilson for knowing how to hold on. And for Mary Ann Hudson for everything else. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vi PARK MEMO RE: THE MYTH OF PROLOGUE 1 PART I. -

4. the Second Coming Summary 2. She Bangs the Drums 1. I Wanna

: r 4 e 3 2 b 1 m 2 u 1 HHEE TTOONNEE OOSSEESS n T S R 0 T S R r 1 3 4 Ian Brown , John Squire2, Gary 'Mani' Mountfield , Alan 'Reni' Wren 2 e t U s 1. Manchester, UK (twitter: @thestoneroses), 2. Manchester, UK, 3. Manchester, UK, 4. Manchester, UK. G o E P 11.. II WWaannnnaa BBee AAddoorreedd 44.. TThhee SSeeccoonndd CCoommiinngg • I don't have to sell my soul, he's already in me. Love Spreads Begging You I don't have to sell my soul, he's already in me. • Love spreads her arms, waits there • The fly on the coachwheel told me that he got it and he knew • I wanna be adored. for the nails. I forgive you, boy, I what to do with it, Everybody saw it, saw the dust that he will prevail. Too much to take, made. King bee in a frenzy, ready to blow, got the horn good to • Adored, I wanna be adored. You adore me. some cross to bear. I'm hiding in go wait. Oh, his sting's all gone, now he's begging you, begging You adore me. You adore me. the trees with a picnic, she's over you. • I wanna be adored. there, yeah. • Here is a warning, the sky will divide. Since I took off the lid, • Let me put you in the picture, let there's nowhere to hide. Now I'm begging you, I'm begging ← Cover of the I Wanna Be Adored single me show you what I mean. -

Undercover Power Play One Friday Afternoon in 1983 the Phone Rang

Undercover Power Play One Friday afternoon in 1983 the phone rang. “Hi, is that Bill Smith? This is Mick Jagger.” Art designer, Bill smith, looked around his studio to see who the prankster was. It was no prank. It was Mick Jagger and he liked the work of Bill Smith Studio. Jagger asked Smith to make a meeting the next Monday and he did. Smith discussed ideas about the new album Undercover with Charlie Watts. Smith was asked to come up with some visuals by that Friday for a band meeting in New York City. Smith was met at JFK airport by a white stretch limo that dropped his stuff at the Central Plaza Hotel and then drove on to Jagger’s New York Residence for a meeting with Jagger, Watts, Ronnie Wood, and Bill Wyman. Smith said, “The cover idea they all loved was a montage of each guy’s head with the head of an animal or a bird or a reptile- ‘undercover’- do you see? I think I prepared two really good montages one of Mick and a cheetah and one of Keith and a panther, the other montages were very rough and needed a lot of work still, to make them really look good, but they all seemed to like the initial idea including the inner bag concept which was some amazing Victorian illustrations of different apple varieties…” Smith’s idea was resurrected in 1992 Jagger told Smith everyone loiked the idea but because by Albert Watson in Los Angeles Keith Richards was not at the meeting he asked Smith where Jagger was photographed with to stay in New York for a few days and complete al the a cheetah for the 25th anniversary of artwork for the album cover and its inner sleeves, while Rolling Stone magazine. -

Intermixx Member and Founder of Miller’S Farm, the Band That Plays a Rather Unique Style of “Country Music for City Folk.”

by Noel Ramos I interviewed Bryan Miller, long time InterMixx member and founder of Miller’s Farm, the band that plays a rather unique style of “country music for city folk.” How did Miller’s Farm get started? The band started as my solo project in 1997 when I quit my full time job and decided to hit music as hard as I could. Pretty quickly I felt the desire to have a band behind me again and I brought in a drummer and a bassist that I'd worked with before in other bands. As we went along, we brought in the soloists (guitar and pedal steel/dobro/harmonica). The sound of the pedal steel/dobro/harmonica really helped focus the direction of the band into the Americana genre, where we are now. As the principal songwriter, what are your inspirations? I've been inspired by a wide range of singers. Robert Plant, Mel Tormé, Jon Anderson, Ray Charles, Paul King (of King)... later, Eddie Vedder, Kurt Cobain. The singers who can not only hit the notes, but can make the song their own. Lyle Lovett has been my most recent and biggest inspiration. From the first time I saw him on Dave Letterman singing "She's No Lady", I have aspired to write like him. Simple melodies, seemingly simple songs full of great description, often humorous with a real sense of honesty. Since then, I've gotten turned on to George Jones, Buck Owens and Hank Thompson, who have some similar qualities. What led you to begin writing "country music for city folk?” Before Miller's Farm, my writing experience was in an 8 piece party band, writing lyrics for music that was already written. -

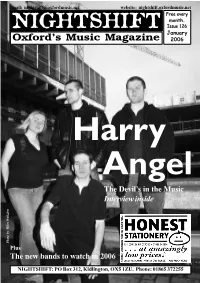

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 126 January Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Harry Angel The Devil’s in the Music Interview inside Photo by Miles Walkden Photo by Miles Plus The new bands to watch in 2006 NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 Evenings and Boywithatoy are among the local NEWNEWSS artists remixing the band. PINDROP PERFORMANCES is a new Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU monthly live music club night launched this Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] month at The Port Mahon in St Clement’s. Pindrop aims to showcase the best up and coming alternative folk and electronic acts THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT will take while the ground floor venue frontage will around. The first night takes place on Sunday place on Wednesday 10th May. Arrangements include a new bar area. A timetable for the 29th January and features Brickwork Lizards, for the annual showcase of the best unsigned refurbishment is yet to be finalised; in the The Thumb Quintet and Dan Glazebrook and music in Oxfordshire, organised by Nightshift, meantime the Zodiac is booking its spring Josie Webber. Each event starts at 5pm and are almost complete, with five venues already programme. Notable gigs already confirmed finishes at 8pm and tickets are limited to 35. confirmed and two more to be confirmed. As include: The Kooks (10th February), Julian Get them from Polar Bear on Cowley Road. ever, the Punt will kick off at Borders in Cope (14th Feb), The Paddingtons (16th Feb), Magdalen Street before moving on to Jongleurs, Regina Spektor (16th Feb), Battle (4th March), OXFORDBANDS.COM has launched an The Wheatsheaf, The City Tavern and finishing The Buzzcocks (5th Mar), Cave In (6th Mar), 65 updated version of its interactive venue guide. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

The Live Album Or Many Ways of Representing Performance

Sergio Mazzanti The live album or many ways of representing ... DOI: 10.2298/MUZ1417069M UDK: 78.067.26 The Live Album or Many Ways of Representing Performance Sergio Mazzanti1 University of Macerata (Macerata) Abstract The analysis of live albums can clarify the dialectic between studio recordings and live performances. After discussing key concepts such as authenticity, space, time and place, and documentation, the author gives a preliminary definition of live al- bums, combining available descriptions and comparing them with different typolo- gies and functions of these recordings. The article aims to give a new definition of the concept of live albums, gathering their primary elements: “A live album is an officially released extended recording of popular music representing one or more actually occurred public performances”. Keywords performance, rock music, live album, authenticity Introduction: recording and performance The relationship between recordings and performances is a central concept in performance studies. This topic is particularly meaningful in popular music and even more so in rock music, where the dialectic between studio recordings and live music is crucial for both artists and the audience. The cultural implications of this jux- taposition can be traced through the study of ‘live albums’, both in terms of recordings and the actual live experience. In academic stud- ies there is a large amount of literature on the relationship between recording and performance, but few researchers have paid attention to this particular -

Texture Messaging NEW YORK — Upholstery Fabrics Have Their Day in the Sun As Stylish, Embellished Looks Turn up in Rich, Textured Brocades and Lush Velvets

NEIMAN’S FIELD NARROWS/3 BOOMERS’ FASHION DIVIDEND/10 WWDWomen’s Wear DailyWEDNESDAY • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • March 23, 2005 • $2.00 Sportswear Texture Messaging NEW YORK — Upholstery fabrics have their day in the sun as stylish, embellished looks turn up in rich, textured brocades and lush velvets. Here, Nanette Lepore’s haute bohemian acrylic, cotton, polyamide and polyester coat, silk and metallic blouse and rayon and silk skirt. Patricia Makena necklace. For more, see pages 6 and 7. From Boho to Beading: India Draws Designers With Exotic Inspirations By Rusty Williamson E JESUS ritish fashion designer Matthew ANK D Williamson has traveled to India B36 times in the last 10 years and is eager to return. His fascination with the country is shared by Oscar de la Renta, Monique Y STAYC ST. ONGE; STYLED BY FR ONGE; STYLED BY ST. Y STAYC Lhuillier, Etro, Roberto Cavalli, Gucci and Tracy Reese, among others, who have embraced colorful and embellished Indian style. This is expressed in the gypsy and bohemian looks; beaded, ABIANA/WOMEN; HAIR AND MAKEUP B mirrored and metallic trims; embroidery; spicy colors, and tie-dye and ikat prints found in numerous collections. See Beyond, Page8 T ABC CARPET AND HOME; MODEL: F PHOTOGRAPHED BY CENTENO A TALAYA 2 WWD, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2005 WWD.COM Li & Fung Sets Sights on $10B by ’07 WWDWEDNESDAY By Scott Malone of them in the market,” he said. Sportswear He also noted that Li & Fung NEW YORK — Looking to extend recently took over the apparel their lead as the world’s largest sourcing operations of Mervyn’s GENERAL MAINSTREAM: Designers are taking inspiration from India, reflected in apparel sourcing company, Li & and Marc Ecko Enterprises. -

Wedding Ceremony Classical Favourites Charts 50'S, 60'S, 70'S

W edding Ceremony Classical Favourites Charts 50’s, 60’s, 70’s, 80’s Charts 90’s, 00’s, Now Christmas Classical Film and TV Jazz, Rags and Tangos Opera and Ballet Scottish & Irish Traditional Video Game Soundtracks ___________ EMAIL | FACEBOOK | TWITTER | YOUTUBE | INSTAGRAM © 2018. The Cairn String Quartet. All Rights Reserved Wedding Ceremony Classical Favourites BACK TO MENU A Thousand Years / Christina Perry Air on a G String / Bach All about You / McFly Ave Maria / Beyonce, Schubert and Gounod Canon / Pachelbel Caledonia / Dougie McLean For the Love of a Princess / Secret Wedding / Braveheart Here Come the Girls turning into Pachelbel’s Canon / Sugababes / Pachelbel Highland Cathedral I Giorno / Einaudi Kissing You / From Romeo and Juliet One Day Like this / Elbow The Final Countdown / Europe Wedding March / Wagner Wedding March / Mendelssohn Wedding March turning into Star Wars / Mendelssohn / Star Wars Wedding March turning into All you Need is Love / Mendelssohn / Beatles Wedding March turning into Another One Bites the Dust / Mendelssohn / Queen Wings / Birdy 500 Miles / the Proclaimers BACK TO MENU EMAIL | FACEBOOK | TWITTER | YOUTUBE | INSTAGRAM © 2018. The Cairn String Quartet. All Rights Reserved Charts 50, 60, 70, 80s BACK TO MENU A Forrest / The Cure A Hard Days Night / The Beatles A Little Help from My Friends / The Beatles A Little respect / Erasure Africa / Toto Ain't No Mountain High Enough / Marvin Gaye/Diana Ross Albatross / Fleetwood Mac All I Want is You