What's It Like to Be Black and Irish?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music-Week-1993-05-0

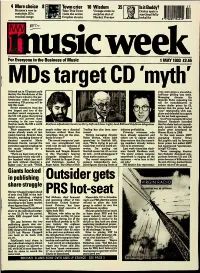

4 Morechoice 8 Town crier 10 Wisdom Kenyon'smaintain vowR3's to Take This Town Vintage comic is musical range visitsCroydon the streets active Marketsurprise Preview star of ■ ^ • H itmsKweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 1 MAY 1993 £2.65 iiistargetCO mftl17 Adestroy forced the eut foundationsin CD prices ofcould the half-hourtives were grillinggiven a lastone-and-a- week. wholeliamentary music selectindustry, committee the par- MalcolmManaging Field, director repeating hisSir toldexaraining this week. CD pricing will be reducecall for dealer manufacturers prices by £2,to twoSenior largest executives and two from of the "cosy"denied relationshipthat his group with had sup- a thesmallest UK will record argue companies that pricing in pliera and defended its support investingchanges willin theprevent new talentthem RichardOur Price Handover managing conceded director thatleader has in mademusic. the UK a world Kaufman adjudicates (centre) as Perry (left) and Ames (right) head EMI and PolyGram délégations atelythat his passed chain hadon thenot immedi-reduced claimsTheir alreadyarguments made will at echolast businesspeople rather without see athose classical fine Tradingmoned. has also been sum- industryPrivately profitability. witnesses who Warnerdealer Musicprice inintroduced 1988. by Goulden,week's hearing. managing Retailer director Alan of recordingsdards for years that ?" set the stan- RobinTemple Morton, managing whose director label othershave alreadyyet to appearedappear admit and managingIn the nextdirector session BrianHMV Discountclassical Centre,specialist warned Music the tionThe was record strengthened companies' posi-last says,spécialisés "We're intrying Scottish to put folk, out teedeep members concem thatalready the commit-believe lowerMcLaughlin prices saidbut addedhe favoured HMV thecommittee music against industry singling for outa independentsweek with the late inclusionHyperion of erwise.music that l'm won't putting be heard oth-out CDsLast to beweek overpriced, committee chair- hadly high" experienced CD sales. -

BTN6916 LMW NORTHERN SOUL ENTS GUIDE SK.Indd

22-25 SEPT 2017 20-23 SEPT 2019 SKEGNESS RESORT GLORIACELEBRATING 60 YEARS JONES OF MOTOWN BOBBY BROOKS WILSON BRENDA HOLLOWAY EDDIE HOLMAN CHRIS CLARK THE FLIRTATIONS TOMMY HUNT THE SIGNATURES FT. STEFAN TAYLOR PAUL STUART DAVIES•JOHNNY BOY PLUS MANY MORE WELCOME TO THE HIGHLIGHTS As well as incredible headliners and legendary DJs, there are loads WORLD’S BIGGEST AND more soulful events to get involved in: BEST NORTHERN SOUL ★ Dance competition with Russ Winstanley and Sharon Sullivan ★ Artist meet and greets SURVIVORS WEEKENDER ★ Shhhh... Battle of the DJs Silent Disco ★ Tune in to Northern Soul BBC – Butlin’s Broadcasting Company Original Wigan Casino jock and founder of the Soul Survivors Weekender, with Russ! Russ Winstanley, has curated another jam-packed few days for you. It’s an ★ incredible line-up with soul legends fl own in from around the world plus a Northern Soul Awards and Dance Competition host of your favourite soul spinners. We’re celebrating Motown Records 60th Anniversary in 2019. To mark this special occasion we have some of the original Motown ladies gracing the stage to celebrate this milestone birthday. SATURDAY 14.00 REDS Meet and Greet with Eddie Holman, Bobby Brooks Wilson, Tommy Hunt Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark and Gloria Jones will also be joining us for a Q&A session, together with Motown afi cionado, Sharon Davies, on Sunday afternoon in Reds. Not to be missed!! SUNDAY 14.00 REDS Don’t miss the Northern Soul dance classes, DJ Battles, Northern Soul Q&A with Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark, Gloria Jones and Sharon Davis awards and dance competitions across the weekend and be sure to look Hosted by Russ Winstanley and Ian Levine, followed by a meet and greet out for limited edition, souvenir vinyl and merch in the Skyline record stall. -

Whalley Range and Around Key

Edition Winter 2013/14 Winter Edition 2 nd Things about Historical facts, trivia and other things of interest Alexandra Park Manley Hall Primitive Methodist College The blitz 1 9 Wealthy textile merchant 12 Renamed Hartley Victoria College after its 16 The bombs started dropping on The beginning: Designed Samuel Mendel built a 50 benefactor Sir William P Hartley, was opened in Manchester during Christmas 1940 with by Alexander Hennell and the Range room mansion in the 1879 to train men to be religious ministers. homes in the Manley Park area taking opened in 1870, the fully + MORE + | CLUBS SPORTS | PARKS | SCHOOLS | HISTORY | LISTINGS | TRIVIA 1860s, with extensive Now known as Hartley Hall, it is an several direct hits. Terraced houses in public park (named after gardens running beyond independent school. Cromwell Avenue were destroyed and are Princess Alexandra) was an Bury Avenue and as far as noticeable by the different architecture. During oasis away from the smog PC Nicholas Cock, a murder Clarendon Road (pictured air raids people would make their way to a of the city and “served to 13 In the 1870s a policeman was fatally wounded left). Mendel’s business shelter, one of which was (and still is!) 2.5m deter the working men whilst investigating a disturbance at a house collapsed when the Suez under Manley Park and held up to 500 people. of Manchester from the near to what was once the Seymour Hotel. The Origins: Whalley Range was one of Manchester’s, and in fact Canal opened and he was The entrance was at the corner of York Avenue alehouses on their day off”. -

For Possible Action - Approval of the Agenda for the Board of County Commissioners’ Meeting of November 20, 2012

NYE COUNTY AGENDA INFORMATION FORM Action LI Presentation LI Presentation & Action Department: Nye County Clerk Agenda Date: Category: Regular Agenda Item January 22, 2013 Continued from meeting of: Contact: Sandra “Sam” Merlino, Nye County Clerk Phone: 482-8127 Return to: Sam Merlino Location: Tonopah Clerk’s Office Phone: 482-8127 Action requested: (Include what, with whom, when, where, why, how much ($) and terms) Discussion and deliberation of Minutes of the Board of County Commissioners’ meeting(s) for November 20, 2012 Complete description of requested action: (Include, if applicable, background, impact, long-term commitment, existing county policy, future goals, obtained by competitive bid, accountability measures) Approval of the BOCC Minutes for the following meeting(s): November 20, 2012 Any information provided after the agenda is published or during the meeting of the Commissioners will require you to provide 20 copies: one for each Commissioner, one for the Clerk, one for the District Attorney, one for the Public and two for the County Manager. Contracts or documents requiring signature must be submitted with three original copies. Expenditure Impact by FY(s): (Provide detail on Financial Form) LI No financial impact Routing & Approval (Sign & Date) 1. Dept Date 6. Dale 2. Dale 7. HR Date Date 1 3• 8. Legal Dal Iici Date 1 4 Da 9. Finance / \ 5 Date io. County Manager PlacQgenda Dale Board of County Commissioners Action Approved Disapproved L1 Amended as follows: Clerk of the Board Date iTEM Page 1 November 20, 2012 Pursuant to NRS the Nye County Board of Commissioners met in regular session at 10:00 a.m. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Life on-air: talk radio and popular culture in Ireland Author(s) Doyle-O'Neill, Finola Editor(s) Ní Fhuartháin, Méabh Doyle, David M. Publication date 2013-05 Original citation Doyle-O'Neill, F. (2013) 'Life on-air: talk radio and popular culture in Ireland', in Ní Fhuartháin, M. and Doyle, D.M. (eds.) Ordinary Irish life: music, sport and culture. Dublin : Irish Academic Press, pp. 128-145. Type of publication Book chapter Link to publisher's http://irishacademicpress.ie/product/ordinary-irish-life-music-sport-and- version culture/ Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, Irish Academic Press. Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/2855 from Downloaded on 2021-09-30T05:50:06Z 1 TALK RADIO AND POPULAR CULTURE “It used to be the parish pump, but in the Ireland of the 1990’s, national radio seems to have taken over as the place where the nation meets”.2 Talk radio affords Irish audiences the opportunity to participate in mass mediated debate and discussion. This was not always the case. Women in particular were excluded from many areas of public discourse. Reaching back into the 19th century, the distinction between public and private spheres was an ideological one. As men moved out of the home to work and acquired increasing power, the public world inhabited by men became identified with influence and control, the private with moral value and support. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

29Th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios by Bob Quinn If Brian

29th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios By Bob Quinn If Brian Dobson, Irish Television’s chief male newsreader had been sacked for his recent breach of professional ethics, pigs would surely have taken to the air over Dublin. Dobson, was exposed as doing journalistic nixers i.e. privately helping to train Health Board managers in the art of responding to hard media questions – from such as Mr. Dobson. When his professional bilocation was revealed he came out with his hands up – live, by phone, on a popular RTE evening radio current affairs programme – said he was sorry, that he had made a wrong call. If long-standing Staff Guidelines had been invoked, he might well have been sacked. Immediately others confessed, among them Sean O’Rourke, presenter of the station’s flagship News At One. He too, had helped train public figures, presumably in the usual techniques of giving soft answers to hard questions. Last year O’Rourke, on the live news, rubbished the arguments of the Chairman of Primary School Managers against allowing advertisers’ direct access to schoolchildren. O’Rourke said the arguments were ‘po-faced’. It transpires that many prominent Irish public broadcasting figures are as happy with part-time market opportunities as Network 2’s rogue builder, Dustin the Turkey, or the average plumber in the nation’s black economy. National radio success (and TV failure) Gerry Ryan was in the ‘stable of stars’ run by Carol Associates and could command thousands for endorsing a product. Pop music and popcorn cinema expert Dave Fanning lucratively opened a cinema omniplex. -

Radio-Radio-Mulryan

' • *427.. • • • • ••• • • • • . RADIO RADIO Peter Mulryan was born in Dublin in 1961. He took an honours degree in Communication Studies from the NIHE, Dublin. He began work as a presenter on RTE's Youngline programme, then moved to Radio 2 as a reporter, before becoming a television continuity announcer and scriptwriter. Since leaving RTE, he has been involved in independent film and video production as well as lecturing in broadcasting. He now lives and works in the UK. PUBLICATIONS RADIO RADIO 813 Peter Mulryan Borderline Publications Dublin, 1988 Published in 1988 by Borderline Publications 38 Clarendon Street Dublin 2 Ireland. CD Borderline Publications ISBN No. 1 870300 033 Computer Graphics by Mark Percival Cover Illustration and Origination by Artworks ( Tel: 794910) Typesetting and Design by Laserworks Co-operative (Tel: 794793) CONTENTS Acknowledgements Preface by the Author Introduction by Dave Fanning 1. The World's First Broadcast 1 2. Freedom and Choice 11 3. Fuse-wire, Black Coffee and True Grit 19 4. Fun and Games 31 5. A Radio Jungle 53 6. Another Kettle of Fish 67 7. Hamburger Radio 79 8. The Plot Thickens 89 9. A Bolt from the Blue 101 10. Black Magic and the Five Deadly Sins 111 11. Bees to Honey 129 12. Twenty Years Ago Today 147 Appendix I - Party Statements Appendix II - The Stations ACKNO WLEDGEMENTS In a book that has consumed such a large and important period of my life, I feel I must take time out to thank all those who have helped me over the years. Since the bulk of this text is built around interviews! have personally conducted, I would like to thank those who let themselves be interviewed (some several times). -

Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019

Saturday 18th May 2019 | 10:00 Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019 Lot 19 Description Estimate 5 x Doo Wop / RnB / Pop 7" singles. The Temptations - Someday (Goldisc £15.00 - £25.00 3001). The Righteous Brothers - Along Came Jones (Verve VK-10479). The Jesters - Please Let Me Love You (Winley 221). Wayne Cochran - The Coo (Scottie 1303). Neil Sedaka - Ring A Rockin' (Guyden 2004) Lot 93 Description Estimate 10 x 1980s LPs to include Blondie (2) Parallel Lines, Eat To The Beat. £20.00 - £40.00 Ultravox (2) Vienna, Rage In Eden (with poster). The Pretenders - 2. Men At Work - Business As Usual. Spandau Ballet (2) Journeys To Glory, True. Lot 94 Description Estimate 5 x Rock n Roll 7" singles. Eddie Cochran (2) Three Steps To Heaven £15.00 - £25.00 (London American Recordings 45-HLG 9115), Sittin' On The Balcony (Liberty F55056). Jerry Lee Lewis - Teenage Letter (Sun 384). Larry Williams - Slow Down (Speciality 626). Larry Williams - Bony Moronie (Speciality 615) Lot 95 Description Estimate 10 x 1960s Mod / Soul 7" Singles to include Simon Scott With The LeRoys, £15.00 - £25.00 Bobby Lewis, Shirley Ellis, Bern Elliot & The Fenmen, Millie, Wilson Picket, Phil Upchurch Combo, The Rondels, Roy Head, Tommy James & The Shondells, Lot 96 Description Estimate 2 x Crass LPs - Yes Sir, I Will (Crass 121984-2). Bullshit Detector (Crass £20.00 - £40.00 421984/4) Lot 97 Description Estimate 3 x Mixed Punk LPs - Culture Shock - All The Time (Bluurg fish 23). £10.00 - £20.00 Conflict - Increase The Pressure (LP Mort 6). Tom Robinson Band - Power In The Darkness, with stencil (EMI) Lot 98 Description Estimate 3 x Sub Humanz LPs - The Day The Country Died (Bluurg XLP1). -

“I Dig the Fact That Four Guys Can Grab the Same Fretless Bass and Sound

Furthermore, says Marco, different gigs demand different atti - tudes: “When I go into a quartet setup, I know there’s going to be a certain amount of freedom in the bass chair. But if it’s a quintet with keyboard and two guitars, my job is more about ““II ddiigg tthhee ffaacctt tthhaatt ffoouurr locking in with the drums and keeping the bottom heavy, groovy, gguuyyss ccaann ggrraabb tthhee ssaammee and fat.” ffrreettlleessss bbaassss aanndd ssoouunndd Mendoza says his favorite playing style is fingerstyle fretless. “For my money, fretless can be a little more expressive than ttoottaallllyy ddiiffffeerreenntt..”” fretted bass. I dig the fact that four guys can grab the same fretless bass and sound totally different, more so than with frets. I understand that certain genres of music need a fretted sound, but I like to think I excel a little more on the fretless.” Yet some of Mendoza’s best-known work was performed with a pick on four-string fretted bass. “On rock sessions, I end up playing with a pick 90-percent of the time, mainly because that’s what the guitar players want. Most rock guitarists have either worked with bass players who used a pick, or they’ve recorded a lot of the bass tracks themselves using a pick. They appreciate the attack of a pick—the clarity, the ping—especial - ly live. Ted Nugent was that way. So was the Thin Lizzy project. Given the opportunity, I’d rather play with my fingers, but I’ve learned to do both and jump between them.” “I guess I’m a chameleon of sorts,” muses session bassist Marco Mendoza. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

Midge Ure (Ultravox)

MUSIC He took us to Vienna, fed the world and now Ultravox frontman Midge Ure is back, writes Sally Browne SPARK t had never really been done before. ‘‘Synthpop’’ and ‘‘ballad’’ were two BURNS words that just didn’t go together. I But in 1981 UK band Ultravox released a single that would become a worldwide hit. It was called Vienna and it combined the grandeur of grand piano and strings with haunting, spare synthesiser beats. The song captured a generation, stayed for a month at No. 2 on the UK charts and was awarded Single of the Year at the Brit Awards for 1981. The video, filmed in its namesake Vienna, also set the trend for music videos to come. It was shot by noted Australian director Russell Mulcahy, who also made classic videos for acts including Duran Duran, Elton John, Culture Club, Bonnie Tyler and Queen. Dramatic and cinematic, the film clip for Vienna was reminiscent of noir film The Third Man, set in spy-filled post-war Austria and starring Orson Welles. The young Scotsman who had penned the lyrics to the unusual song had never been to Vienna until that time. ‘‘It wasn’t until we actually went to the city, I realised that what I’d imagined in my head was kind of real, this decaying Still playing: Ultravox elegance, this beautiful city,’’ Midge Ure frontman Midge Ure has a new says today. album after all these years. The band had taken a big risk to shoot the video there. They took out a loan of 7000 pounds to fund it.