The Court Case of the Mouse Against the Cat: a Casebook of Versions Recorded in Recent Decades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, October 26, 2017 NEWS CHART ACTION Kid Rock Announces November Album Release, New On The Chart —Debuting This Week Artist/song/label—chart pos. Tour Set For 2018 Ross Clayton/Turn Up Again/Big Palm Entertainment — 71 Brad Paisley/Heaven South/Arista Nashville — 73 Smith & Wesley/Superman For A Day/Dream Walkin' Records — 77 Greatest Spin Increase Artist/song/label—Spin Increase Midland/Make A Little/Big Machine — 253 Brett Young/Like I Loved You/BMLG — 208 Tim McGraw & Faith Hill/The Rest Of Our Life/Arista Nashville — 201 Russell Dickerson/Yours/Triple Tigers Records — 189 LANCO/Greatest Love Story/Arista Nashville — 178 Jon Pardi/She Ain't In It/Capitol Nashville — 171 Chris Young/Losing Sleep/Sony Music — 168 Blake Shelton/I'll Name The Dogs/Warner Bros. — 160 Most Added Artist/song/label—No. of Adds Jon Pardi/She Ain't In It/Capitol Nashville — 16 Tim McGraw & Faith Hill/The Rest Of Our Life/Arista Nashville — 12 Chris Lane feat. Tori Kelly/Take Back Home Girl/Big Loud — 12 Brad Paisley/Heaven South/Arista Nashville — 10 Kid Rock will release his debut album for BBR Music Group, titled Sweet Dustin Lynch/I’d Be Jealous Too/Broken Bow Records — 7 Southern Sugar, on Nov. 3. The eclectic album marks the irst Kid Rock has Russell Dickerson/Yours/Triple Tigers Records — 5 recorded in Nashville, and includes his recent single “Tennessee Mountain Shenandoah/Noise — 5 Top.” To read the full article, click here. Lady Antebellum/Heart Break/Capitol — 5 Brett Eldredge/The Long Way/Atlantic/Warner Music Nashville/WEA Kelsea Ballerini, Reba, Maren Morris, Naill Horan Radio & Streaming — 5 Set For CMA Awards Collaborations Maren Morris feat. -

Gate of Heaven, Saint Brigid & St. Monica-St. Augustine Parishes

St. Monica --- St. Augustine, Gate of heaven & Saint Brigid of Kildare Parishes South Boston, MA From the cloud came a voice: “This is my beloved Son. Listen to him.” SSecondecond Sunday of Lent March 1, 2015 Gate of Heaven, St Brigid, St Monica-St Augustine Parishes South Boston, MA Parish Information and Mass Schedule Gate of Heaven Church Saint Brigid Church 615 East Fourth Street, South Boston 841 East Broadway, South Boston MASS SCHEDULE: MASS SCHEDULE: Daily Mass: Monday - Friday at 9:00 a.m. Daily Mass: Monday - Friday at 7:00am Weekend: Saturday at 4:00 p.m. Weekend: Saturday at 4:00 p.m. Sunday at 9:00 a.m. and 12 noon Sunday at 8:00 a.m., 10:30 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. CONFESSION: CONFESSION: Saturday 3:30 p.m. - 3:50 p.m. Saturday 3:30 p.m. - 3:50 p.m. Saint Monica Church Saint Augustine Chapel 331 Old Colony Ave, South Boston 181 Dorchester Street, South Boston MASS SCHEDULE: MASS SCHEDULE: Sunday: 9:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. (Spanish) Saturday at 4 p.m. PARISH STAFF Pastor: Rev. Robert E. Casey Parochial Vicar: Rev. Eric M. Bennett Priest in Residence: Msgr. Liam Bergin Pastoral Associate: Mr. Javier Soegaard Business Manager: Mrs. Jo-Ann Geary Director of Religious Education KK----6:6: Mr. James Fowkes Confirmation Coordinator Grade 77----9:9: Mrs. Mea Quinn Mustone Music Director, Organist: Ms. Carolyn Martin Tuition Coordinator, South Boston Catholic Academy: Mrs. Kathy Meoli Secretaries: Mrs. Patricia Strumm, Mrs. Carol Glenn, Ms. -

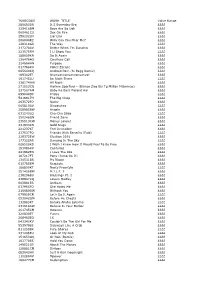

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

GES1005/SSA1208 Temple Visit Report Bao Gong Temple

GES1005/SSA1208 Temple Visit Report Bao Gong Temple 包公庙 Yuan Yongqing Janice Ng Su Li Li Peng Bei Ding ZhongNi Tutorial Group: D1 App Profile ID:224 1. Introduction Our group was assigned to visit Bao Gong Temple, which is part of the Jalan Kayu Joint Temple located at 70 Sengkang West Avenue. Despite the small scale, it is regarded as a holy place by numerous worshippers and it is the only temple named after Bao Gong among all the Singapore temples consecrating him. The Bao Gong Temple Council have dedicated considerable efforts to public welfare which attracted more devotees. They even supervised a publication of The Book for the Treasures of Singapore Bao Gong Temple (《新加坡包公庙典藏书》) in 2015 to further spread Bao Gong culture and to document the history of the temple. A free PDF version can be found on the temple website https://www.singaporebaogongtemple.com. We would like to express our gratitude here to the Chief of general affairs, Master Chen Yucheng (H/P: 82288478) for his generous help throughout our visit. 2. The Folk Belief in Bao Gong The belief of Bao Gong was derived from the folklores of Bao Zheng (999-1062). Born in Hefei, Bao Zheng started rendering government service in 1037 and gained continuous promotion from the then highest ruler, Emperor Renzong of Song in the next 26 years. Among all his political achievements, he was most well-known for the impartial adjudication when he served as the mayor of Kaifeng (the capital of Northern Song). Remediating corruption and impeaching guilty nobles, Bao Zheng always upheld the interests of the masses, was loyal to the nation and disciplined himself. -

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts Barend J. ter Haar During the last decade or so, social historians in China and the United States seem to have reached a new consensus on the origins of the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui; "society" is the usual translation for hui, which, strictly speaking, means "gathering"; for the sake of brevity, the phenomenon is referred to below with the common alternative name "Triad," a translation of sänke hui). They view the Triads äs voluntary brotherhoods organized for mutual support, which later developed into a successful predatory tradition. Supporters of this Interpretation react against an older view, based on a literal reading of the Triad foundation myth, according to which the Triads evolved from pro-Ming groups during the early Qing dynasty. The new Interpretation relies on an intimate knowledge of the official documents that were produced in the course of perse- cuting these brotherhoods on the mainland and on Taiwan since the late eigh- teenth Century. The focus of this recent research has been on specific events, resulting in a more detailed factual knowledge of the phenomenon than before (Cai 1987; Qin 1988: 1—86; Zhuang 1981 provides an excellent historiographical survey). Understandably, contemporary social historians have hesitated to tackle the large number of texts produced by the Triads because previous historians have misinterpreted them and because they are füll of obscure religious Information and mythological references. Nevertheless, the very fact that these texts were produced (or copied) continuously from the first years of the nineteenth Century —or earlier—until the late 1950s, and served äs the basis for Triad initiation rituals throughout this period, leaves little doubt that they were important to the members of these groups. -

A Songbook May.2017

ARTIST TITLE SONG TITLE ARTIST 4:00 AM Fiona, Melanie 12:51 Strokes, The 3 Spears, Britney 11 Pope, Cassadee 22 Swift, Taylor 24 Jem 45 Shinedown 73 Hanson, Jennifer 911 Jean, Wyclef 1234 Feist 1973 Blunt, James 1973 Blunt, James 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1982 Travis, Randy 1982 Travis, Randy 1985 Bowling For Soup 1994 Aldean, Jason 21875 Who, The #1 Nelly (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana (Kissed You) Good Night (Instrumental Version) Gloriana (you Drive Me) Crazy Spears, Britney (You Want To) Make A Memory Bon Jovi (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher And Higher McDonald, Michael 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1 2 3 4 Feist 1 Thing Amerie 1 Thing Amerie 1 Thing Amerie 1,2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 1,2,3,4 Plain White T's 10 Out Of 10 Lou, Louchie 10,000 Towns Eli Young Band 10,000 Towns (Instrumental Version) Eli Young Band 100 Proof Pickler, Kellie 100 Proof (Instrumental Version) Db Pickler, Kellie 100 Years Five For Fighting 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 1-2-3-4 Sumpin' New Coolio 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 15 Minutes (Backing Track) Atkins, Rodney 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee 15 Minutes Of Shame (Backing Track) B Cook, Kristy Lee 16 at War Karina 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. 18 And Life Skid Row 18 And Life Skid Row 19 And Crazy Bomshel 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark 19 You and Me Dan + Shay 19 You and Me (Instrumental Version) Dan + Shay 19-2000 Gorillaz 1994 (Instrumental Version) Aldean, Jason 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The ARTIST TITLE 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Becomes 1 Spice Girls 2 Faced Louise 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie 2 Step DJ Unk 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 20 Years And 2 Husbands Ago Womack, Lee Ann 21 Questions 50 Cent Feat. -

The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Journal of Cambridge Studies 1 The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief Yongyi YUE Beijing Normal University, P.R. China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Although the Zushiye (Grand Masters) belief is in some degree similar with the Worship of Ancestors, it obviously has its own characteristics. Before the mid-twentieth century, the belief of King Zhuang of Zhou (696BC-682BC), the Zushiye of many talking and singing sectors, shows that except for the group cult, the Zushiye belief which is bodily practiced in the form of kowtow as a basic action also dispersed in the group everyday life system, including acknowledging a master (Baishi), art-learning (Xueyi), marriage, performance, identity censorship (Pandao) and master-apprentice relationship, etc. Furthermore, the Zushiye belief is not only an explicit rite but also an implicit one: a thinking symbol of the entire society, special groups and the individuals, and a method to express the self and the world in inter-group communication. The Zushiye belief is not only “the nature of mind” or “the mentality”, but also a metaphor of ideas and eagerness for equality, as well as relevant behaviors. Key Words: Belief, Bodily practices, Everyday life, Legends, Subjective experience Yongyi YUE, Associate Professor, Folklore and Cultural Anthropology Institute, College of Chinese Language and Literature, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, PRC Volume -

The Political Aspect of Misogynies in Late Qing Dynasty Crime Fiction

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, April 2016, Vol. 6, No. 4, 340-355 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.04.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Political Aspect of Misogynies in Late Qing Dynasty Crime Fiction Lavinia Benedetti University of Catania, Catania, Italy In most Chinese traditional court-case narrative, women often serve as negative social actors, and may even be the alleged cause of the degeneration of men’s morality as the result of their seductiveness. In the late Qing Dynasty novel Digong’an, centred on the upright official Digong, there is strong evidence of misogyny by the author. Two female characters stand out from the story: one kills her husband with the help of her lover, who is partially justified by the latter being under the woman’s negative influence; and the other is Empress Wu, to whom the moral downfall of the Tang Dynasty is attributed. Both women are subject to insult and threat throughout the novel. The author’s attitude substantially relies on the sexist rhetoric prevalent in the Confucian idea of an ordered society, which usually took a negative outlook towards women partaking in public life. But for the latter we should also take in account that at the end of the Qing Dynasty a woman was, in reality, ruling the empire “from behind the curtain”. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to deconstruct the author’s misogyny, in order to shed a light on his criticism and connect it with a somewhat more political discourse. Keywords: Chinese courtcase novel, Digong’an, political criticism, Empress Cixi Introduction Crime and punishment are much appreciated themes in Chinese narrative production since its very beginning. -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

十六shí Liù Sixteen / 16 二八èr Bā 16 / Sixteen 和hé Old Variant of 和/ [He2

十六 shí liù sixteen / 16 二八 èr bā 16 / sixteen 和 hé old variant of 和 / [he2] / harmonious 子 zǐ son / child / seed / egg / small thing / 1st earthly branch: 11 p.m.-1 a.m., midnight, 11th solar month (7th December to 5th January), year of the Rat / Viscount, fourth of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] 动 dòng to use / to act / to move / to change / abbr. for 動 / 詞 / |动 / 词 / [dong4 ci2], verb 公 gōng public / collectively owned / common / international (e.g. high seas, metric system, calendar) / make public / fair / just / Duke, highest of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] / honorable (gentlemen) / father-in 两 liǎng two / both / some / a few / tael, unit of weight equal to 50 grams (modern) or 1&frasl / 16 of a catty 斤 / [jin1] (old) 化 huà to make into / to change into / -ization / to ... -ize / to transform / abbr. for 化 / 學 / |化 / 学 / [hua4 xue2] 位 wèi position / location / place / seat / classifier for people (honorific) / classifier for binary bits (e.g. 十 / 六 / 位 / 16-bit or 2 bytes) 乎 hū (classical particle similar to 於 / |于 / [yu2]) in / at / from / because / than / (classical final particle similar to 嗎 / |吗 / [ma5], 吧 / [ba5], 呢 / [ne5], expressing question, doubt or astonishment) 男 nán male / Baron, lowest of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] / CL:個 / |个 / [ge4] 弟 tì variant of 悌 / [ti4] 伯 bó father's elder brother / senior / paternal elder uncle / eldest of brothers / respectful form of address / Count, third of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] 呼 hū variant of 呼 / [hu1] / to shout / to call out 郑 Zhèng Zheng state during the Warring States period / surname Zheng / abbr. -

Das Prognosesystem Qimen Dunjia

Titel: Kognitive Divinationskünste im Kaiserlichen China: das Prognosesystem Qimen Dunjia zum Erreichen des Doktorgrades eingereicht im Fachbereich Sinologie FB Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaft der Freien Universität Berlin im Feburar, 2012 vorgelegt von Alejandro Peñataro Sánchez aus Alicante (Spanien) Tag der Disputation: 10. Juli 2012 1. Gutachter/in: Prof. Dr. phil. Dr. phil. habil. Dr. med. habil. M.P.H. Paul U. Unschuld 2. Gutachter/in: Prof. Dr. Klaus Mühlhahn 2 Widmung und Danksagung: A mi amor y toda mi familia, con cariño, a todos los que somos, los que nos dejaron su legado y los que vendrán. 奉獻給鐘義明及李貢銘 I dedicate this dissertation to all those persons who throughout my life have helped me and honored me with their friendships. 3 Kognitive Divinationskünste im Kaiserlichen China: das Prognosesystem Qimen Dunjia Inhaltverzeichnis Liste der Abbildungen und Tabellen, S. 7 I. Einführende Bemerkungen zum allgemeinen historischen Kontexts, S. 10 II. Einführende Betrachtungen zum konzeptuellen Fundament, S. 16 III. Zur Konzeption und Präsentation der Forschung, S. 20 IV. Bestimmung der Haupthypothesen der Untersuchung, S. 24 1. Grundlegende Konzeptionen, S. 26 1.1 Prognoseerstellung im chinesichen Altertum, S. 26 1.2 Prognosestellung und Entscheidungsfindung als Grundlage erfolgreichen Handelns, S. 32 1.3 Die Rolle der Weissagung im chinesischen Kriegswesen, S. 33 2. Versuch einer Definition des Qimen Dunjia, S. 37 2.1 Die Ausgangslage einer Definition, S. 37 2.2 Etymologische Herleitungen anhand der Referenzliteratur, S. 39 2.3 Grundlegende Rahmenkonzepte, S. 42 2.4 Etymologische Erläuterungen aus der Sicht der Fachliteratur, S. 44 2.5 Weitere historische Darstellungen des Qimen Dunjia, S. 47 3. Die unterschiedlichen Typen des Qimen Dunjia, S.