Class Actions in Canada: a National Procedure in a Multi-Jurisdictional Society?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Clinique De Médiation De L'université

LE MAGAZINE DES JURISTES DU QUÉBEC 4$ Volume 24, numéro 6 La Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal et ses partenaires : se mobiliser pour l’accès à la justice Dans l’ordre habituel de gauche à droite, de bas en haut : Mme Rielle Lévesque (Coordonnatrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Sherbrooke) , Dr Maya Cachecho (Chercheure post- doctoral et coordonnatrice scientifique du Projet de recherche ADAJ), Me Laurent Fréchette (Président du Comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, Chambre des notaires du Québec), Pr Pierre-Claude Lafond (Professeur à l’Université de Montréal, membre du Groupe RéForMa et membre du Comité scientifique de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Me Hélène de Kovachich (Juge administratif et fondatrice-directrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Pr Marie-Claude Rigaud (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et directrice du Groupe RéForMa), Pr Catherine Régis (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et membre du Groupe RéForMa), Me Ariane Charbonneau (Directrice générale d’Éducaloi), Mme Anja-Sara Lahady (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), Mme Laurie Trottier-Lacourse (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), L’Honorable Henri Richard (Juge en chef adjoint à la chambre civile de la Cour du Québec), M Serge Chardonneau (Directeur général d’Équijustice), Mme Laurence Codsi (Présidente du Comité Accès à la Justice), Me Nathalie Croteau (Secrétaire-trésorière de l’IMAQ), Me Marie Annik Gagnon (Juge administratif coordonateur section des affaires sociales, TAQ), -

Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:21 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A. Macdonald The Legacy of Roncarelli v. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Article abstract L’héritage de l’affaire Roncarelli c. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Given the inclination of legal scholars to progressively displace the meaning of Volume 55, Number 3, September 2010 a judicial decision from its context toward abstract propositions, it is no surprise that at its fiftieth anniversary, Roncarelli v. Duplessis has come to be URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1000618ar interpreted in Manichean terms. The complex currents of postwar society and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1000618ar politics in Quebec are reduced to a simple story of good and evil in which evil is incarnated in Duplessis’s “persecution” of Roncarelli. See table of contents In this paper the author argues for a more nuanced interpretation of the case. He suggests that the thirteen opinions delivered at trial and on appeal reflect several debates about society, the state and law that are as important now as half a century ago. The personal socio-demography of the judges authoring Publisher(s) these opinions may have predisposed them to decide one way or the other; McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill however, the majority and dissenting opinions also diverged (even if unconsciously) in their philosophical leanings in relation to social theory ISSN (internormative pluralism), political theory (communitarianism), and legal theory (pragmatic instrumentalism). Today, these dimensions can be seen to 0024-9041 (print) provide support for each of the positions argued by Duplessis’s counsel in 1920-6356 (digital) Roncarelli given the state of the law in 1946. -

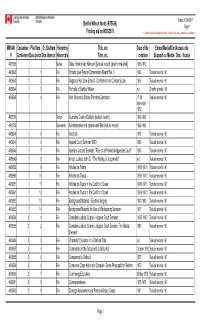

Bertha Wilson Fonds (R15636) Finding Aid No MSS2578 MIKAN

Date: 21/06/2017 Bertha Wilson fonds (R15636) Page 1 Finding aid no MSS2578 Y:\App\Impromptu\Mikan\Reports\Description_reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers_simplelist.im MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent/Media/Dim/Access cde # Contenant Dos./pièce Dos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 4938705 Series Osler, Hoskin and Harcourt [textual record, graphic material] 1965-1972 4939542 1 1 File Ontario Law Reform Commission Report No. 1 1965 Textual records / 90 4939543 1 2 File Osgoode Hall Law School - Conference on Company Law 1965 Textual records / 90 4939544 1 3 File Portraits of Bertha Wilson n.d Graphic (photo) / 90 4939545 1 4 File York Un ive rsity Estate Planning Seminars 17-18 Textual records / 90 November 1972 4938706 Series Supreme Court of Ontario [textual record] 1962-1982 4938708 Sub-series Administrative and operational files [textual record] 1962-1982 4939546 1 5 File Abortion 1976 Textual records / 90 4939547 1 6 File Appeal Court Seminar 1980 1980 Textual records / 90 4939548 1 7 File Apellate Judges' Seminar, "Role of a Provincial Appellate Court" 1980 Textual records / 90 4939549 1 8 File Arnup, Justice John D., "The Writing of Judgments" n.d Textual records / 90 4939550 1 9 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939550 1 10 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 11 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict of Laws [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 12 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

MSS2101 Graphic 1--4; 108--110.Xlsx

John Sopinka fonds MG31-E120 Finding aid no MSS2101 vols. 1--110; 07447; TCS 01429 R1312 Instrument de recherche no MSS2101 Hier. lvl. Media Label File Item Title Scope and content Vol. Dates Niv. Support Étiquette Dossier Pièce Titre Portée et contenu hier. John Sopinka fonds Activities as Justice at the Supreme Court of Canada Bench books 22 June 1989 - 7 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 1 Bench Book No. 1 1989 6 Dec. 1989 - 23 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 2 Bench Book No. 2 1990 26 Mar. 1990 - 12 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 1 3 Bench Book No. 3 1990 29 Oct. 1990 - 27 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 1 4 Bench Book No. 4 1991 28 Feb. 1991 - 4 July File Textual MG31-E120 1 5 Bench Book No. 5 1991 1 Oct. 1991 - 9 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 6 Bench Book No. 6 1991 10 Dec. 1991 - 25 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 7 Bench Book No. 7 1992 26 May 1992 - 11 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 2 1 Bench Book No. 8 1992 25 Jan. 1993 -27 May File Textual MG31-E120 32 1 Bench Book No. 9 1993 31 May 1993- 26 Jan. File Textual MG31-E120 32 2 Bench Book No. 10 1994 27 Jan. 1994 - 4 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 32 3 Bench Book No. 11 1993 4 Oct. 1994 - 23 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 32 4 Bench Book no. 12 1995 24 Feb. 1995 - 3 Nov. File Textual MG31-E120 32 5 Bench Book No. -

Claire L'heureux-Dub6 and the Career Prospects for Early Female Law Graduates from Laval University

"We Don't Hire a Woman Here": Claire L'Heureux-Dub6 and the Career Prospects for Early Female Law Graduates from Laval University Constance Backhouse" Claire L'Heureux-Dub, a bold and renowned member of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1987 to 2002, was among the first twenty women to graduatefrom Laval University's Faculty of Law. As a detourfrom the larger project of writing Claire's biography, the author offers insights into the events in Claire'slife that led her to a successful career inpnvatepractice, 2014 CanLIIDocs 33497 which at that time was virtually the only route to a judicial appointment. Perhaps the most pivotal of those events was the fact that when she was admitted to the bar, Sam Schwarz Bard, theprivatepractitionerforwhom she had been working as a secretary, had the breadth ofvision to immediately take her on as a lawyer and to mentor her through the early years ofher career. The author compares Claire'spath with the more meandering careerpathsof most of the other early Lavalfemale law graduates,and unpacks the dauntingchallenges they faced in establishing and pursuing a career in law. Among those challenges were open gender bias, unwelcoming male colleagues, marriage, self limiting expectations and a lack of information about career opportunities.By way ofcontrast,the authorlooks at thestrikingly more direct careertrajectories ofsome of their male classmates. * Professor of Law, University of Ottawa. I would like to thank my research assistants, Falon Milligan, Emelie Kozak and Jessica Kozak, and my administrative assistant, Veronique Larose. David Wexler of the Faculty of Law, University of Puerto Rico, offered many valuable insights to this work. -

Roderick A. Macdonald*

McGill Law Journal ~ Revue de droit de McGill WAS DUPLESSIS RIGHT? Roderick A. Macdonald* Given the inclination of legal scholars to Étant donné la tendance qu’ont les juristes progressively displace the meaning of a judicial à extraire la signification d’une décision judiciaire decision from its context toward abstract propo- de son contexte pour l’amener vers des proposi- sitions, it is no surprise that at its fiftieth anni- tions abstraites, il n’est pas surprenant que versary, Roncarelli v. Duplessis has come to be l’arrêt Roncarelli c. Duplessis, dont c’est le cin- interpreted in Manichean terms. The complex quantième anniversaire, soit interprété d’une currents of postwar society and politics in Que- manière manichéenne. Les courants sociopoliti- bec are reduced to a simple story of good and ques complexes du Québec de l’après-guerre evil in which evil is incarnated in Duplessis’s sont réduits à une simple histoire de bien et de “persecution” of Roncarelli. mal dans laquelle la « persécution » de Roncarelli In this paper the author argues for a more par Duplessis incarne le mal. nuanced interpretation of the case. He suggests Dans cet essai, l’auteur propose une inter- that the thirteen opinions delivered at trial and prétation plus nuancée de l’arrêt. Il suggère que on appeal reflect several debates about society, les treize jugements prononcés en première in- the state and law that are as important now as stance et en appel reflètent plusieurs débats sur half a century ago. The personal socio-demography la société, sur l’État et sur le droit qui sont tout of the judges authoring these opinions may have aussi pertinents aujourd’hui qu’il y a un demi- predisposed them to decide one way or the siècle. -

Parliamentary Sovereignty Rests with the Courts:” the Constitutional Foundations of J

Title Page “Parliamentary sovereignty rests with the courts:” The Constitutional Foundations of J. G. Diefenbaker’s Canadian Bill of Rights Jordan Birenbaum Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jordan Birenbaum, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Abstract The 1980s witnessed a judicial “rights revolution” in Canada characterized by the Supreme Court of Canada striking down both federal and provincial legislation which violated the rights guaranteed by the 1982 Charter of Rights. The lack of a similar judicial “rights revolution” in the wake of the 1960 Canadian Bill of Rights has largely been attributed to the structural difference between the two instruments with the latter – as a “mere” statute of the federal parliament – providing little more than a canon of construction and (unlike the Charter) not empowering the courts to engage in judicial review of legislation. Yet this view contrasts starkly with how the Bill was portrayed by the Diefenbaker government, which argued that it provided for judicial review and would “prevail” over other federal legislation. Many modern scholars have dismissed the idea that the Bill could prevail over other federal statutes as being incompatible with the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. That is, a bill of rights could only prevail over legislation if incorporated into the British North America Act. As such, they argue that the Diefenbaker government could not have intended the Bill of Rights to operate as anything more than a canon of construction. However, such a view ignores the turbulence in constitutional thinking on parliamentary sovereignty in the 1930s through 1960s provoked by the Statute of Westminster. -

Sujit Choudhry* & Jean-François Gaudreault-Desbiens** FRANK

Sujit Choudhry* & Jean-Franc¸ois Gaudreault-DesBiens** FRANK IACOBUCCI AS CONSTITUTION MAKER: FROM THE QUEBEC VETO REFERENCE TO THE MEECH LAKE ACCORD AND THE QUEBEC SECESSION REFERENCE † I Introduction Frank Iacobucci occupies a unique place in Canadian constitutional history. As a Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada for thirteen years, he played a central role in the development of Canadian constitutional jurisprudence. Yet prior to his appointment to the bench, he served as deputy attorney-general of Canada between 1985 and 1988 and was a principal member of the federal team in the negotiations over the Meech Lake Accord. This accord was not only a legal but also a political document, reflecting and advancing a view of Quebec’s place in the fed- eration and proposing a set of constitutional amendments that would have implemented that vision. Although the negotiations failed, we are arguably still living with the consequences of that failure today. Does exploring Iacobucci’s views on his role as constitution maker during the Meech Lake saga shed light on his subsequent career as con- stitutional interpreter on the bench? As Brian Dickson: A Judge’s Journey1 reminds us, in the Canadian legal academy, biography is both an import- ant and an underutilized source of insight on the judicial mind. In Iacobucci’s case, his career prior to his judicial appointment is all the more valuable as a source of insight because of his central role in the poli- tics of constitutional reform. The natural place to explore this link is the case in which the Court was thrust into the heart of the national unity dispute – the Secession Reference.2 One of the most puzzling aspects of the judgment, which has thus far escaped attention, is its curiously selective account of consti- tutional history. -

Church..Evicts Day Care His Request for Documents Were up for Negotiation

.'A,ILIA g,J, ~LD~;S V£.C~TORZA B C Alcan route for hydro, oil, rail Northern corridor may kill Kitimat line PRINCE RUPERT, 'B.C. to the West Coast, as a the northwest to a host of ",We can do it several move our northern produc- developments in the north crude oil has to be found on He said, however, that if (CP) --An oil pipeline nation builder in the true other developments. times over. We can build a tion, oil as well as gas, to the ndamay move this way. Metals the Canadian side of the big Canadian oil pools are paralleling the AlasKa lligh- sense of the word," he said. "As more oil reserves are largediameter oil line down highest price markets in other minerals will, Alaska-Yukon Boundary." found quickly in the north, it way natural gaspipeline is Even if big oil discoveries developed around Prudhse the Alaska Highway. North America. even some forest products. "It has to be found in large will make a Kitimat oil line inevitable, Jack Davis, are slow in coming, said the Bay, off-shore and on-shore, "We can pipe Alaskan' Oil "In transportation terms I "A railway link could be quantities in the MeKenzie redundant. British Columbia energy, minister, and even if a economists and engineers down from Edmonton see a big new northwest economic in time. And, with Delta or offshore where "Believe me, I'm not transport and com- Kitimat-toEdmonton oil will say what we can do with through the Inter-provincial corridor developing... all this happening, Canada's Dome Petroleum is ex- mentioning a Kitimat oil munications minister, said pipeline is built, "an oil line as we can do with oil," Oil Pipeline System to "Who know? Electricity two major transportation ploring now," he said. -

“Class Roots: the Genesis of the Ontario Class Proceedings Act, 1966-1993”

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by YorkSpace “Class Roots: The Genesis of the Ontario Class Proceedings Act, 1966-1993” Suzanne Chiodo A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Laws Graduate Program in Law, York University, Toronto, Ontario November 2016 © Suzanne Chiodo, 2016 Abstract Nearly 25 years since its passage, the Ontario Class Proceedings Act has become one of the most frequently debated procedural mechanisms of its kind. The CPA came about following the release of the Attorney General’s Advisory Committee (AGAC) Report in 1990. None of the current narratives explain how this Report pulled together so many divergent interests where previous attempts had failed. My thesis answers this question with reference to the historical sources and the legal, political and social changes that took place throughout this period. This thesis also highlights the unique nature of the AGAC consultation process, which saw the negotiation of a consensus between the parties and the subsequent drafting of legislation. Although this process was effective, however, it led to compromises and a lack of democratic oversight that continue to affect the CPA and its goals of access to justice to this day. ii Table of Contents ABSTRACT II TABLE OF CONTENTS III CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 A. OVERVIEW 1 B. WHY A HISTORICAL STUDY OF THE CPA? 4 C. LITERATURE REVIEW 7 D. METHODOLOGY 13 E. TERMINOLOGY 14 F. SCOPE AND STRUCTURE 17 CHAPTER 2: CLASS ACTIONS IN ENGLAND, NORTH AMERICA, AUSTRALIA 19 A. -

Tradition Et Modernité À La Faculté De Droit De L'université Laval De 1945 À 1965 Sylvio Normand

Document generated on 09/25/2021 5:12 p.m. Les Cahiers de droit Tradition et modernité à la Faculté de droit de l'Université Laval de 1945 à 1965 Sylvio Normand Volume 33, Number 1, 1992 Article abstract For two decades—from 1945 to 1965 — the Laval University Law Faculty was to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/043129ar undergo profounds changes. At the outset, the school was shrouded in a veil of DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/043129ar tradition and whatever hints of change to be manifested were fiercely combatted. With the onset of the Quiet Revolution, when Quebec society itself See table of contents was in profound transition, the law Faculty becomes the subject of indepth questioning. Under pressure from the student body — which benefitted from widespread popular support—Faculty authorities were to acquiesce to Publisher(s) substantial changes. Faculté de droit de l’Université Laval ISSN 0007-974X (print) 1918-8218 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Normand, S. (1992). Tradition et modernité à la Faculté de droit de l'Université Laval de 1945 à 1965. Les Cahiers de droit, 33(1), 141–187. https://doi.org/10.7202/043129ar Tous droits réservés © Faculté de droit de l’Université Laval, 1992 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal.