Sujit Choudhry* & Jean-François Gaudreault-Desbiens** FRANK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief Justice Rued Abortion Ruling, Book Says

Chief justice rued abortion ruling, book says Text based on Dickson's private papers gives insight into Supreme Court rulings By KIRK MAKIN From Friday's Globe and Mail (December 5, 2003) Years after he voted to reverse Henry Morgentaler's 1974 jury acquittal on charges of performing illegal abortions, chief justice Brian Dickson of the Supreme Court of Canada began to regret his harsh decision, says a new book on the late legendary judge. He stepped down from the bench in 1990 and died in 1998 at the age of 82. "In retrospect, it may not have been the wisest thing to do," chief justice Dickson is quoted as saying in the book, based on interviews and 200 boxes of private papers. He was privately horrified by a defence strategy predicated on Dr. Morgentaler's belief that an individual can ignore the law if his cause is sufficiently virtuous, according to the authors of Brian Dickson: A Judge's Journey . When Dr. Morgentaler again came before the court in 1988, chief justice Dickson suddenly found himself holding the swing vote during a private conference of the seven judges who heard the case. With his brethren deadlocked 3-3, the book says, chief justice Dickson saw a way to come full circle. This time, he voted to strike down the abortion law. However, he based his decision on the unconstitutionality of a cumbersome procedure for approving abortions, allowing him to uphold the acquittal but avoid sanctifying Dr. Morgentaler's decision to flout the law. "Dickson now accepted many of the same arguments that had failed to move him or any member of the Court in the Morgentaler 1," say the authors, Ontario Court of Appeal Judge Robert Sharpe and Kent Roach, a University of Toronto law professor. -

La Clinique De Médiation De L'université

LE MAGAZINE DES JURISTES DU QUÉBEC 4$ Volume 24, numéro 6 La Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal et ses partenaires : se mobiliser pour l’accès à la justice Dans l’ordre habituel de gauche à droite, de bas en haut : Mme Rielle Lévesque (Coordonnatrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Sherbrooke) , Dr Maya Cachecho (Chercheure post- doctoral et coordonnatrice scientifique du Projet de recherche ADAJ), Me Laurent Fréchette (Président du Comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, Chambre des notaires du Québec), Pr Pierre-Claude Lafond (Professeur à l’Université de Montréal, membre du Groupe RéForMa et membre du Comité scientifique de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Me Hélène de Kovachich (Juge administratif et fondatrice-directrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Pr Marie-Claude Rigaud (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et directrice du Groupe RéForMa), Pr Catherine Régis (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et membre du Groupe RéForMa), Me Ariane Charbonneau (Directrice générale d’Éducaloi), Mme Anja-Sara Lahady (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), Mme Laurie Trottier-Lacourse (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), L’Honorable Henri Richard (Juge en chef adjoint à la chambre civile de la Cour du Québec), M Serge Chardonneau (Directeur général d’Équijustice), Mme Laurence Codsi (Présidente du Comité Accès à la Justice), Me Nathalie Croteau (Secrétaire-trésorière de l’IMAQ), Me Marie Annik Gagnon (Juge administratif coordonateur section des affaires sociales, TAQ), -

A Rare View Into 1980S Top Court

A rare view into 1980s top court New book reveals frustrations, divisions among the judges on the Supreme Court By KIRK MAKIN JUSTICE REPORTER Thursday, December 4, 2003- Page A11 An unprecedented trove of memos by Supreme Court of Canada judges in the late 1980s reveals a highly pressured environment in which the court's first female judge threatened to quit while another judge was forced out after plunging into a state of depression. The internal memos -- quoted in a new book about former chief justice Brian Dickson -- provide a rare view into the inner workings of the country's top court, which showed itself to be badly divided at the time. The book portrays a weary bench, buried under a growing pile of complex cases and desperately worried about its eroding credibility. One faction complained bitterly about their colleagues' dithering and failure to come to grips with their responsibilities, according to memos seen for the first time by the authors of Brian Dickson: A Judge's Journey. The authors -- Mr. Justice Robert Sharpe of the Ontario Court of Appeal and University of Toronto law professor Kent Roach -- also interviewed many former judges and ex-clerks privy to the inner workings of the court at arguably the lowest point in its history. "The court was struggling with very difficult issues under very difficult circumstances at the time," Prof. Roach said yesterday. "It was a court that had an incredible amount on its plate and, in retrospect, we were well served by that court." The chief agitators were Mr. Justice Antonio Lamer and Madam Justice Bertha Wilson. -

An Unlikely Maverick

CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND 795 “THE MAVERICK CONSTITUTION” — A REVIEW OF CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND, WILLIAM KAPLAN (TORONTO: UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS FOR THE OSGOODE SOCIETY FOR CANADIAN LEGAL HISTORY, 2009) When a man has risen to great intellectual or moral eminence; the process by which his mind was formed is one of the most instructive circumstances which can be unveiled to mankind. It displays to their view the means of acquiring excellence, and suggests the most persuasive motive to employ them. When, however, we are merely told that a man went to such a school on such a day, and such a college on another, our curiosity may be somewhat gratified, but we have received no lesson. We know not the discipline to which his own will, and the recommendation of his teachers subjected him. James Mill1 While there is today a body of Canadian constitutional jurisprudence that attracts attention throughout the common law world, one may not have foreseen its development in 1949 — the year in which appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (Privy Council) were abolished and the Supreme Court of Canada became a court of last resort. With the exception of some early decisions regarding the division of powers under the British North America Act, 1867,2 one would be hard-pressed to characterize the Supreme Court’s record in the mid-twentieth century as either groundbreaking or original.3 Once the Privy Council asserted its interpretive dominance over the B.N.A. -

RT. HON. BRIAN DICKSON, P.C. CHIEF JUSTICE of CANADA "Law

RT. HON. BRIAN DICKSON, P.C. CHIEF JUSTICE OF CANADA "Law and Medicine: Conflict or Collaboration?" Cushing Oration American Association of Neurological Surgeons Toronto, April 25, 1988 - 2 - I INTRODUCTION I have the honour of coming before you as the Cushing orator. Perhaps it is wishful thinking on my part, but I like to imagine that Harvey Cushing would have accepted your selection of me as the one to deliver this year's Oration. Dr. Cushing took a serious interest in ethical questions.1 Ethics and law are inextricably bound. Dr. Cushing also worked closely with Sir William Osler, a truly great Canadian. For his biography of Osler,2 Dr. Cushing won the Pulitzer Prize. Dr. Cushing was a man of wide interests, perhaps even sufficiently wide to tolerate the prospect of a Canadian lawyer giving a lecture dedicated to his memory. Doctors and lawyers have much in common. We are both members of learned professions with long and proud histories. Both professions have highly developed ethical codes. 1 Pellegrino, E.D., "`The Common Devotion' - Cushing's Legacy and Medical Ethics Today" (1983) 59 J. Neurosurg. 567. 2 The Life of Sir William Osler (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 1925. - 3 - Dedication to the welfare of patient or client is our primary guide. Doctors and lawyers, however, often find themselves in apparent conflict, particularly where a patient seeks compensation from a doctor for alleged negligence or malpractice. The lawyer's task is to do the best he or she can for the client, and in cases of medical malpractice, this will be at the expense of the doctor. -

Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:21 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A. Macdonald The Legacy of Roncarelli v. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Article abstract L’héritage de l’affaire Roncarelli c. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Given the inclination of legal scholars to progressively displace the meaning of Volume 55, Number 3, September 2010 a judicial decision from its context toward abstract propositions, it is no surprise that at its fiftieth anniversary, Roncarelli v. Duplessis has come to be URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1000618ar interpreted in Manichean terms. The complex currents of postwar society and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1000618ar politics in Quebec are reduced to a simple story of good and evil in which evil is incarnated in Duplessis’s “persecution” of Roncarelli. See table of contents In this paper the author argues for a more nuanced interpretation of the case. He suggests that the thirteen opinions delivered at trial and on appeal reflect several debates about society, the state and law that are as important now as half a century ago. The personal socio-demography of the judges authoring Publisher(s) these opinions may have predisposed them to decide one way or the other; McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill however, the majority and dissenting opinions also diverged (even if unconsciously) in their philosophical leanings in relation to social theory ISSN (internormative pluralism), political theory (communitarianism), and legal theory (pragmatic instrumentalism). Today, these dimensions can be seen to 0024-9041 (print) provide support for each of the positions argued by Duplessis’s counsel in 1920-6356 (digital) Roncarelli given the state of the law in 1946. -

Criminal Fault As Per the Lamer Court and the Ghost of William Mcintyre

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 33 Issue 1 Volume 33, Number 1 (Spring 1995) Article 3 1-1-1995 Criminal Fault as Per the Lamer Court and the Ghost of William McIntyre Michael J. Bryant Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Bryant, Michael J.. "Criminal Fault as Per the Lamer Court and the Ghost of William McIntyre." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 33.1 (1995) : 79-103. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol33/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Criminal Fault as Per the Lamer Court and the Ghost of William McIntyre Abstract Contrary to recent criticisms to the effect that the Supreme Court of Canada favours the rights of criminal defendants and shuns the interests of the community, the Lamer Court has in fact championed the moral requisites of the community in its constitutional jurisprudence on criminal fault. By viewing rights and responsibilities as inextricably linked, the Lamer Court implicitly borrows from natural law traditions espoused by the Dickson Court's most conspicuous dissenter on criminal fault issues-Mr. Justice William McIntyre. This article argues that the tradition or philosophy underlying criminal fault as per the Lamer Court contrasts with the individualist, rights-oriented tendency of the Dickson Court, and corresponds with the approach of William McIntyre. -

No Brexit-Type Vote for Canada We Have the Clarity Act

For Immediate Release July 1, 2016 ARTICLE / PRESS RELEASE No Brexit-Type Vote For Canada We Have The Clarity Act Bill C-20, passed by the Parliament of Canada in the late 1990’s, otherwise known as the ‘Clarity Act’, ensures that all Canadians are fairly and democratically represented by a way of a “clear expression of a will by a clear majority of the population.” While the bill was drafted in response to the less-than-clear Quebec referendum question in both 1980 and 1995, it applies to all provinces. The Clarity Act is an integral component of our federalist system and seeks to protect Canadians from an underrepresented and unclear referendum question. I had the distinct honour as Deputy Unity Critic under Leader Preston Manning to strongly martial Reform Party Support for acceptance. The Clarity Act served to balance the pre-requisite of all societal organizations and constitutions that call for 66% (or two-thirds) of voter support for substantive changes that diametrically impact all members (read citizens) existing rights and those that wish for only 50% + 1 for change, because these changes will be difficult to reverse when enacted. The Clarity Act cites over 10 times that approval for referendum must be determined by a clear expression by a clear majority of the population eligible to vote. This means that a majority of all eligible voters must be considered, not just those who show up at the polls to vote. Furthermore, the Supreme Court of Canada, agreeing with Bill C-20, specifies that any proposal relating to the constitutional makeup of a democratic state is a matter of utmost gravity and is of fundamental importance to all of its citizens. -

The 1992 Charlottetown Accord & Referendum

CANADA’S 1992 CHARLOTTETOWN CONSTITUTIONAL ACCORD: TESTING THE LIMITS OF ASYMMETRICAL FEDERALISM By Michael d. Behiels Department of History University of Ottawa Abstract.-Canada‘s 1992 Charlottetown Constitutional Accord represented a dramatic attempt to transform the Canadian federation which is based on formal symmetry, albeit with a limited recognition of some asymmetry, into an asymmetrical federal constitution recognizing Canada‘s three nations, French, British, and Aboriginal. Canadians were called up to embrace multinational federalism, one comprising both stateless and state-based nations exercising self-governance in a multilayered, highly asymmetrical federal system. This paper explores why a majority of Canadians, for a wide variety of very complex reasons, opted in the first-ever constitutional referendum in October 1992 to retain their existing federal system. This paper argues that the rejection of a formalized asymmetrical federation based on the theory of multinational federalism, while contributing to the severe political crisis that fueled the 1995 referendum on Quebec secession, marked the moment when Canadians finally became a fully sovereign people. Palacio de la Aljafería – Calle de los Diputados, s/n– 50004 ZARAGOZA Teléfono 976 28 97 15 - Fax 976 28 96 65 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Charlottetown Consensus Report, rejected in a landmark constitutional referendum on 26 October 1992, entailed a profound clash between competing models of federalism: symmetrical versus asymmetrical, and bi-national versus multinational. (Cook, 1994, Appendix, 225-249) The Meech Lake Constitutional Accord, 1987-90, pitted two conceptions of a bi-national -- French-Canada and English Canada – federalism against one another. The established conception entailing a pan-Canadian French-English duality was challenged and overtaken by a territorial Quebec/Canada conception of duality. -

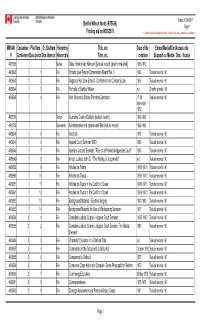

Bertha Wilson Fonds (R15636) Finding Aid No MSS2578 MIKAN

Date: 21/06/2017 Bertha Wilson fonds (R15636) Page 1 Finding aid no MSS2578 Y:\App\Impromptu\Mikan\Reports\Description_reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers_simplelist.im MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent/Media/Dim/Access cde # Contenant Dos./pièce Dos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 4938705 Series Osler, Hoskin and Harcourt [textual record, graphic material] 1965-1972 4939542 1 1 File Ontario Law Reform Commission Report No. 1 1965 Textual records / 90 4939543 1 2 File Osgoode Hall Law School - Conference on Company Law 1965 Textual records / 90 4939544 1 3 File Portraits of Bertha Wilson n.d Graphic (photo) / 90 4939545 1 4 File York Un ive rsity Estate Planning Seminars 17-18 Textual records / 90 November 1972 4938706 Series Supreme Court of Ontario [textual record] 1962-1982 4938708 Sub-series Administrative and operational files [textual record] 1962-1982 4939546 1 5 File Abortion 1976 Textual records / 90 4939547 1 6 File Appeal Court Seminar 1980 1980 Textual records / 90 4939548 1 7 File Apellate Judges' Seminar, "Role of a Provincial Appellate Court" 1980 Textual records / 90 4939549 1 8 File Arnup, Justice John D., "The Writing of Judgments" n.d Textual records / 90 4939550 1 9 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939550 1 10 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 11 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict of Laws [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 12 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict -

Council of the Federation

Constructive and Co-operative Federalism? A Series of Commentaries on the Council of the Federation Council of the Federation: An Idea Whose Time has Come J. Peter Meekison* Foreword In 2001 a Special Committee of the Quebec Canada’s Provincial and Territorial Premiers Liberal Party proposed the creation of a Council agreed in July 2003 to create a new Council of the of the Federation.1 Newly elected Quebec Federation to better manage their relations and ultimately to build a more constructive and Premier Jean Charest put this proposal, in cooperative relationship with the federal modified form, before the Annual Premiers government. The Council’s first meeting takes Conference in July 2003. The concept of place October 24, 2003 in Quebec hosted by establishing an institution such as the Council has Premier Jean Charest. been raised before in the context of constitutional reform, particularly in the period between the This initiative holds some significant promise 1976 Quebec election and the 1981 constitutional of establishing a renewed basis for more extensive patriation agreement. More recently the matter collaboration among governments in Canada, but was raised during the negotiations leading to the many details have yet to be worked out and several important issues arise that merit wider attention. 1992 Charlottetown Accord. The purpose of this paper is to examine its antecedents. Others The Institute of Intergovernmental Relations at writing in this series of articles on the Council of Queen’s University and the Institute for Research the Federation (Council) will comment in greater on Public Policy in Montreal are jointly publishing detail on the specifics of the Quebec proposal. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982.