Ends of War. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Past and New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Dušan Šarotar, Born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, Is a Writer, Poet and Screenwri- [email protected] Ter

Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. He studied Sociology of Culture and www.zalozba.org Philosophy at the University of Ljublja- www.readcentral.org na. He has published two novels (Island of the Dead in 1999 and Billiards at the Translation: Gregor Timothy Čeh Dušan Šarotar Hotel Dobray in 2007), three collecti- ons of short stories (Blind Spot, 2002, Editor: Renata Zamida Author’s Catalogue Layout: designstein.si Bed and Breakfast, 2003 and Nostalgia, Photo: Jože Suhadolnik, Dušan Šarotar 2010) and three poetry collections (Feel Proof-reading: Catherine Fowler, for the Wind, 2004, Landscape in Minor, Marianne Cahill 2006 and The House of My Son, 2009). Ša- rotar also writes puppet theatre plays Published by Beletrina Academic Press© and is author of fifteen screenplays for Ljubljana, 2012 documentary and feature films, mostly for television. The author’s poetry and This publication was published with prose have been included into several support of the Slovene Book Agency: anthologies and translated into Hunga- rian, Russian, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Czech and English. In 2008, the novel Billiards at the Hotel Dobray was nomi- nated for the national Novel of the Year Award. There will be a feature film ba- ISBN 978-961-242-471-8 sed on this novel filmed in 2013. Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. -

Fall 2011 / Winter 2012 Dalkey Archive Press

FALL 2011 / WINTER 2012 DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS CHAMPAIGN - LONDON - DUBLIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2010 SANDROF LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Award FROM THE NatiONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE what’s inside . 5 The Truth about Marie, Jean-Philippe Toussaint 6 The Splendor of Portugal, António Lobo Antunes 7 Barley Patch, Gerald Murnane 8 The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, Kjersti A. Skomsvold 9 The No World Concerto, A. G. Porta 10 Dukla, Andrzej Stasiuk 11 Joseph Walser’s Machine, Gonçalo M. Tavares Perfect Lives, Robert Ashley (New Foreword by Kyle Gann) 12 Best European Fiction 2012, Aleksandar Hemon, series ed. (Preface by Nicole Krauss) 13 Isle of the Dead, Gerhard Meier (Afterword by Burton Pike) 14 Minuet for Guitar, Vitomil Zupan The Galley Slave, Drago Jančar 15 Invitation to a Voyage, François Emmanuel Assisted Living, Nikanor Teratologen (Afterword by Stig Sæterbakken) 16 The Recognitions, William Gaddis (Introduction by William H. Gass) J R, William Gaddis (New Introduction by Robert Coover) 17 Fire the Bastards!, Jack Green 18 The Book of Emotions, João Almino 19 Mathématique:, Jacques Roubaud 20 Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Veteranyi (Afterword by Vincent Kling) 21 Iranian Writers Uncensored: Freedom, Democracy, and the Word in Contemporary Iran, Shiva Rahbaran Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955–2010), Christopher Domínguez Michael 22 Autoportrait, Edouard Levé 23 4:56: Poems, Carlos Fuentes Lemus (Afterword by Juan Goytisolo) 24 The Review of Contemporary Fiction: The Failure Issue, Joshua Cohen, guest ed. Available Again 25 The Family of Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela 26 On Elegance While Sleeping, Viscount Lascano Tegui 27 The Other City, Michal Ajvaz National Literature Series 28 Hebrew Literature Series 29 Slovenian Literature Series 30 Distribution and Sales Contact Information JEAN-PHILIPPE TOUSSAINT titles available from Dalkey Archive Press “Right now I am teaching my students a book called The Bathroom by the Belgian experimentalist Jean-Philippe Toussaint—at least I used to think he was an experimentalist. -

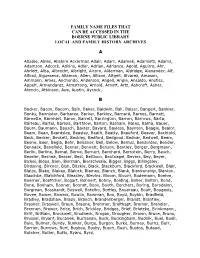

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Obituaries Buffalo News 2010 by Name

Obituaries as found in the Buffalo News: 2010 Date of Place of Date, Page of Last Name/Maiden First Name M.I. Age Death Death/Birth/Residence Date, Page detailed obit Abbarno Vincent "Lolly" A. 9/26/2010 Kenmore, NY 9-30-2010: C4 Abbatte/Saunders Murielle A. 87 1/11/2010 1-13-2010: B4 Abbo Joseph D. 57 5/31/2010 Lewiston, NY 6-3-2010: B4 Brooksville, FL; formerly of Abbott Casimer "Casey" 12/19/22009 Cheektowaga, NY 4-18-2010: C6 Abbott Phillip C. 3/31/2010 4-3-2010: B4 Abbott Stephen E. 7/6/2010 7-8-2010: B4 Abbott/Pfoetsch Barbara J. 4/20/2010 5-2-2010: B4 Abeles Esther 95 1/31/2010 2-4-2010: C4 Abelson Gerald A. 82 2/1/2010 Buffalo, NY 2-3-2010: B4 Abraham Frank J. 94 3/21/2010 3-23-2010: B4 Abrahams/Gichtin Sonia 2/10/2010 died in California 2-14-2010: C4 Abramo Rafeala 93 12/16/2010 12-19-2010: C4 Abrams Charlotte 4/6/2010 4-8-2010: B4 Abrams S. "Michelle" M. 37 5/21/2010 Salamanca, NY 5-23-2010: B4 Abrams Walter I. 5/15/2010 Basom, NY 5-19-2010: B4 Abrosette/Aksterowicz Sister Mary 6/18/2010 6-19-2010: C4 Refer to BEN 2-21-2010: B6/7/8 for more possible Abshagen Charles, Jr. L. 73 2/19/2010 North Tonawanda, NY 2-22-2010: B8 information Acevedo Miguel A. 10/6/2010 Buffalo, NY 10-27-2010: B4 Achkar John E. -

PDF Presentation

Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau Located in German-occupied Poland, Auschwitz consisted of three camps including a killing center. The camps were opened over the course of nearly two years, 1940-1942. Auschwitz closed in January 1945 with its liberation by the Soviet army. More than 1.1 million people died at Auschwitz, including nearly one million Jews. Those who were not sent directly to gas chambers were sentenced to forced labor. The Auschwitz complex differed from the other Nazi killing centers because it included a concentration camp and a labor camp as well as large gas chambers and crematoria at Birkenau constructed for the mass murder of European Jews. Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Hoecker/Auschwitz Albums Photo Analysis United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Auschwitz Album The "Auschwitz Album" specifically depicts the arrival of Hungarian Jews and the selection process that the SS imposed upon them. Lili Jacob (later Zelmanovic Meier), was deported with her family to Auschwitz in late May 1944 from Bilke (today: Bil'ki, Ukraine), a small town which was then part of Hungary. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION “We were taught as children”—I was told by a seventy- year-old Pole—“that we Poles never harmed anyone. A partial abandonment of this morally comfortable position is very, very difficult for me.” —Helga Hirsch, a German journalist, in Polityka, 24 February 2001 HE COMPLEX and often acrimonious debate about the charac- ter and significance of the massacre of the Jewish population of T the small Polish town of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941—a debate provoked by the publication of Jan Gross’s Sa˛siedzi: Historia za- głady z˙ydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny, 2000) and its English translation Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton, 2001)—is part of a much wider argument about the totali- tarian experience of Europe in the twentieth century. This controversy reflects the growing preoccupation with the issue of collective memory, which Henri Rousso has characterized as a central “value” reflecting the spirit of our time.1 One key element in the understanding of collec- tive memory is the “dark past” of nations—those aspects of the na- tional past that provoke shame, guilt, and regret; this past needs to be integrated into the national collective identity, which itself is continu- ally being reformulated.2 In this sense, memory has to be understood as a public discourse that helps to build group identity and is inevita- bly entangled in a relationship of mutual dependence with other iden- tity-building processes. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Variability of Throughfall and Stemflow Deposition in Pine and Beech Stands ( Czarne Lake Catchment, Gardno Lake Catchment on Wolin Island )

PrACE GEOGrAfICzNE, zeszyt 143 Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ Kraków 2015, 85 – 102 doi : 10.4467/20833113PG.15.027.4628 Variability of throughfall and stemflow deposition in pine and beech stands ( Czarne lake catchment, gardno lake catchment on wolin island ) Robert Kruszyk, Andrzej Kostrzewski, Jacek Tylkowski Abstract : The research sought to determine the range of conversion of the chemical composition of precipitation in a beech stand located in the Gardno Lake catchment ( Wolin Island ) and a pine stand in the Czarne Lake catchment ( Upper Parsęta catchment, West Pomerania Province ). The presented results cover three hydrological years : 2012, 2013 and 2014. The research focused on the chemical composition of bulk precipitation ( in the open ), throughfall and stemflow ( in a forest ). The obtained results confirm that after precipitation has had contact with plant surfaces there is an increase in its mineral content. This is due to the process of enrichment of throughfall and stemflow with elements leached out of needles + 2+ + – + 2+ 2– – and leaves ( K , Mg ) and coming from dry deposition ( NH 4, Cl , Na , Mg , SO 4 , NO 3 ) washed out from plant surfaces. The research, based on the canopy budget model, indicates that in the case of potassium, its load leached out of needles and leaves accounted for 75.6 % and 73 %, respectively, of its total deposition on the forest floor. Calcium leaching was not detected in either of the two stands. In comparison with potassium, the range of magnesium leaching was smaller and amounted to 34 % under beech and 26.5 % under pine. As to loads of potassium and magnesium in the beech stand, they were more than twice as large as the ones observed in the pine stand. -

Academic Year 1995/96

* * * * * * ■k * * * EDUCATION TRAINING YOUTH TEMPUS Compendium ACADEMIC YEAR 1995/96 Phare EUROPEAN COMMISSION Prepared for the European Commission Directorate-General XXII - Education, Training and Youth by the u European Training Foundation Villa Guatino Viale Settimio Severo 65 1-10133 Torino ITALY Tel.: (39)11-630.22.22 Fax: (39)11-630.22.00 E-mail: [email protected]. The European Training Foundation, which is an independent agency of the European Union, was established to support and coordinate activities between the EU and partner countries in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia in the field of education and training, and assists the European Commission in the implementation of the Tempus Scheme. * * * * * * * ** * EDUCATION TRAINING YOUTH TEMPUS Compendium ACADEMIC YEAR 1995/96 Phare EUROPEAN COMMISSION Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1995 ISBN 92-827-5476-6 © ECSC-EC-EAEC, Brussels · Luxembourg, 1995 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium o OS H INTRODUCTION The Tempus Programme Tempus (trans-European cooperation scheme for higher education), now in its sixth academic year of existence, was adopted on 7 May 1990 . The second phase (Tempus II), covering the period 1994-98 was adopted on 23 April 1993 . Tempus forms part of the overall European Union assistance programmes for the social and economic restructuring of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, known as the Phare Programme, and, since the beginning of its second phase, also for the New Independent States and Mongolia, known as the Tacis Programme. -

Young American Journalists in Germany and Poland International Summer Academy the Faces of Justice Auschwitz Album Revisited

O Ś WIĘ CIM ISSN 1899-4407 PEOPLE CULTURE HISTORY YOUNG AMERICAN JOURNALISTS IN GERMANY AND POLAND INTERNATIONAL SUMMER ACADEMY THE FACES OF JUSTICE AUSCHWITZ ALBUM REVISITED no. 31 July 2011 Oś—Oświęcim, People, History, Culture magazine, no. 31, July 2011 EDITORIAL BOARD: Oś—Oświęcim, People, History, Culture magazine EDITORIAL Last month, the Jewish Center host- Their authors were Rodryg Romer, Site? Gerhard Hausmann, a lecturer ed FASPE project participants, on his daughter Elżbieta, and her fi ancé at this German institution, answers which we reported in the previous Maksymilian Lohman, who were im- this question in an interview in this issue of the monthly. Among them prisoned in Auschwitz in 1943. Fam- Oś. were young journalists as well as ily members of the former prisoners students from the Columbia Univer- donated these priceless heirlooms. We also invite you to visit the ex- Editor: sity in New York. In this issue of Oś, Within this Oś, we also summarize hibition at the International Youth Paweł Sawicki we are publishing their texts, which the fi rst International Summer Acad- Meeting Center. For the fi rst time Editorial secretary: were the effect of the ten-day pro- emy, which was prepared for teach- in Poland, the works of Pat Mercer Agnieszka Juskowiak-Sawicka gram. To start with, we have chosen ers from abroad by the International Hutchens are on display. In total this Editorial board: general refl ections and descriptions Center for Education about Ausch- includes twenty-fi ve reproductions Bartosz Bartyzel Wiktor Boberek of the entire visit, as well as a text witz and the Holocaust; as well as of oil paintings, which are an artis- Jarek Mensfelt written by Eugene Kwibuka from report on a visit to the Memorial tic and literary interpretation from Olga Onyszkiewicz Rwanda, who, in a particularly emo- Site by members of the International the infamous Auschwitz Album.