Victorian Steam Locomotives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluctuations in the Energetic Properties of a Spark-Ignition Engine Model with Variability

Entropy 2013, 15, 3277-3296; doi:10.3390/e15083367 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Fluctuations in the Energetic Properties of a Spark-Ignition Engine Model with Variability Pedro L. Curto-Risso 1, Alejandro Medina 2, Antonio Calvo-Hernandez´ 3, Lev Guzman-Vargas´ 4;* and Fernando Angulo-Brown 5 1 Instituto de Ingenier´ıa Mecanica´ y Produccion´ Industrial, Universidad de la Republica,´ Montevideo 11300, Uruguay; E-Mail: pcurto@fing.edu.uy 2 Departamento de F´ısica Aplicada, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca 37008, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Departamento de F´ısica Aplicada and IUFFYM, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca 37008, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Unidad Profesional Interdisciplinaria en Ingenier´ıa y Tecnolog´ıas Avanzadas, Instituto Politecnico´ Nacional, Av. IPN 2580, L. Ticoman,´ Mexico D.F. 07340, Mexico 5 Departamento de F´ısica, Escuela Superior de F´ısica y Matematicas,´ Instituto Politecnico´ Nacional, Edif. No. 9 U.P. Zacatenco, Mexico D. F. 07738, Mexico; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-55-57296000 ext. 56873; Fax: +52-55-57529318. Received: 8 June 2013; in revised form: 30 July 2013 / Accepted: 13 August 2013 / Published: 19 August 2013 Abstract: We study the energetic functions obtained in a simulated spark-ignited engine that incorporates cyclic variability through a quasi-dimensional combustion model. Our analyses are focused on the effects of the fuel-air equivalence ratio of the mixture simultaneously over the cycle-to-cycle fluctuations of heat release (QR) and the performance outputs, such as the power (P ) and the efficiency (η). -

Newsletter 155 Spring 2012

NEWSLETTER 155 SPRING 2012 Puddlers’ Bridge on the Trevithick Trail, near Merthyr Tydfil. Reg. Charity 1 No. 246586 CHAIRMAN’S ADDRESS Creating links The recent opening of the Sustrans bridge, covered elsewhere in this issue, to connect two lengths of the Trevithick Trail near Merthyr Tydfil came about a year after the University of Swansea published an investigation into the Welsh Copper Industry.* Both these significant events in industrial history depended upon Cornwall’s links with Wales. In the first instance, Richard Trevithick’s ingenuity and development of the high- pressure steam engine in Cornwall took form as the world’s first steam powered railway locomotive in Wales. It is well known for having pulled a train loaded with 10 tons of iron and some 70 passengers nearly ten miles. This was 25 years before the emergence of George Stephenson’s Rocket. The second event depended mainly on the little sailing ships that carried thousands of tons of copper ore from Cornwall and returned with the Welsh coal and iron that powered Cornwall’s mines and fed its industries. Investigations have shown that much of the copper smelting in Wales and shipping was controlled by Cornish families. Cornwall had similar industrial links to Bridgnorth, Dartford and other places throughout the country; all depended to a great extent upon Cornish ingenuity. This Society appears to be the only link today between Cornwall’s industrial archaeology and that of other parts of the country. If we are to encourage the study of Cornwall’s industrial archaeology we need to develop these links for the benefit of all concerned, wherever they may be. -

Newsletter 180 Summer 2018

NEWSLETTER 180 SUMMER 2018 Robert Metcalfe leading the AGM weekend walk around Wheal Owles. Reg. Charity 1 No. 1,159,639 the central machinery hall, and consists of REPUTED TREVITHICK a single-cylinder return crank engine of the ENGINE vertical type, which there is every reason to consider it being one of Richard Trevithick’s design. Whilst it bears no maker’s name nor any means of direct identification, it presents so many well-known Trevithick features that it may be pretty certainly set down as a product of the ingenuity of the Father of High-pressure Steam. The engine was employed for over fifty years, down to 1882, at some salt works at Ingestre, Staffordshire, on the Earl’s estate. Prior to that it had been used for the winding at a colliery at Brereton, near Rugeley, and is thought to have been built at Bridgnorth. It is known that Haseldine and Co, of that place, built many engines to Trevithick’s design, under agreement with him. The engine is somewhat later than the other examples of his, close by, and is therefore of peculiar interest in enabling the course of gradual improvement to be easily followed. Thanks to Peter Coulls, the Almost everything about the request for a copy of The Engineer article machine is of cast iron, and probably its (Volume 113, page 660 (21st June 1912) original boiler was too. This, however, had about the mystery Reputed Trevithick long disappeared - they generally burst High-pressure Engine was successful. A - steam having been supplied at Ingestre copy of the article promptly arrived in the by an egg-ended boiler, 8.5 ft long by post and is reproduced here in full: 3 ft in diameter, set with a partial wheel draught and working at 35 lb pressure. -

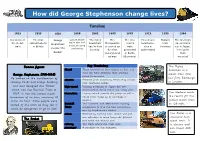

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

History of the Automobile

HISTORY OF THE AUTOMOBILE Worked by: Lara Mateus nº17 10º2 Laura Correia nº18 10º2 Leg1: the first car. THE EARLY HISTORY The early history of the automobile can be divided into a number of eras, based on the prevalent means of propulsion. Later periods were defined by trends in exterior styling, size, and utility preferences. In 1769 the first steam powered auto-mobile capable of human transportation was built by Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot. In 1807, François Isaac de Rivaz designed the first car powered by an internal combustion engine fueled by hydrogen. In 1886 the first petrol or gasoline powered automobile the Benz Patent-Motorwagen was invented by Karl Benz.This is also considered to be the first "production" vehicle as Benz made several identical copies. FERDINAND VERBIEST Ferdinand Verbiest, a member of a Jesuit mission in China, built the first steam-powered vehicle around 1672 as a toy for the Chinese Emperor. It was of small enough scale that it could not carry a driver but it was, quite possibly the first working steam-powered vehicle. Leg2: Ferdinand Verbiest NICOLAS-JOSEPH CUGNOT Steam-powered self-propelled vehicles large enough to transport people and cargo were first devised in the late 18th century. Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot demonstrated his fardier à vapeur ("steam dray"), an experimental steam-driven artillery tractor, in 1770 and 1771. As Cugnot's design proved to be impractical, his invention was not developed in his native France. The center of innovation shifted to Great Britain. NICOLAS-JOSEPH CUGNOT By 1784, William Murdoch had built a working model of a steam carriage in Redruth. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 25 June 1 4/2010/00006843 AIR21 GLOBAL AIR21 GLOBAL, INC. [PH] 35 and39 2010 20 2 4/2012/00011594 September AAA SUNQUAN LU [PH] 19 2012 11 May 3 4/2012/00501163 CACATIAN, LEUGIM D [PH] 25 2012 24 4 4/2012/00740257 September MIX N` MAGIC MICHAELA A TAN [PH] 30 2012 11 June NEUROGENESIS 5 4/2013/00006764 LBI BRANDS, INC. [CA] 32 2013 HAPPY WATER BABAYLAN SPA AND ALLIED 6 4/2013/00007633 1 July 2013 BABAYLAN 44 INC. [PH] 12 July OAKS HOTELS & M&H MANAGEMENT 7 4/2013/00008241 43 2013 RESORTS LIMITED [MU] 25 July DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY 8 4/2013/00008867 DAIWA HOUSE 36; 37 and42 2013 CO., LTD. [JP] 16 August ELLEBASY MEDICALE ELLEBASY MEDICALE 9 4/2013/00009840 35 2013 TRADING TRADING [PH] 9 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE 10 4/2013/00010788 September UNSTOPABLES 3 COMPANY [US] 2013 9 October BELL-KENZ PHARMA INC. -

Lean's Engine Reporter and the Development of The

Trans. Newcomen Soc., 77 (2007), 167–189 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Lean’s Engine Reporter and the Development of the Cornish Engine: A Reappraisal by Alessandro NUVOLARI and Bart VERSPAGEN THE ORIGINS OF LEAN’S ENGINE REPORTER A Boulton and Watt engine was first installed in Cornwall in 1776 and, from that year, Cornwall progressively became one of the British counties making the most intensive use of steam power.1 In Cornwall, steam engines were mostly employed for draining water from copper and tin mines (smaller engines, called ‘whim engines’ were also employed to draw ore to the surface). In comparison with other counties, Cornwall was characterized by a relative high price for coal which was imported from Wales by sea.2 It is not surprising then that, due to their superior fuel efficiency, Watt engines were immediately regarded as a particularly attractive proposition by Cornish mining entrepreneurs (commonly termed ‘adventurers’ in the local parlance).3 Under a typical agreement between Boulton and Watt and the Cornish mining entre- preneurs, the two partners would provide the drawings and supervise the works of erection of the engine; they would also supply some particularly important components of the engine (such as some of the valves). These expenditures would have been charged to the mine adventurers at cost (i.e. not including any profit for Boulton and Watt). In addition, the mine adventurer had to buy the other components of the engine not directly supplied by the Published by & (c) The Newcomen Society two partners and to build the engine house. -

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED the LIVE STEAM SCENE

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED THE LIVE STEAM SCENE fredlub |SNCF231E | 8 februari 2021 1 Content 1 Content ................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 3 1975 - 1985 .......................................................................................................................... 6 Southern Railway Schools Class .................................................................................................................... 6 JNR 8550 .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 V&T RR Reno ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Old Faithful ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Shay Class B ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 JNR C12 ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 PLM 231A ..................................................................................................................................................... -

RT Rondelle PDF Specimen

RAZZIATYPE RT Rondelle RAZZIATYPE RT RONDELLE FAMILY Thin Rondelle Thin Italic Rondelle Extralight Rondelle Extralight Italic Rondelle Light Rondelle Light Italic Rondelle Book Rondelle Book Italic Rondelle Regular Rondelle Regular Italic Rondelle Medium Rondelle Medium Italic Rondelle Bold Rondelle Bold Italic Rondelle Black Rondelle Black Italic Rondelle RAZZIATYPE TYPEFACE INFORMATION About RT Rondelle is the result of an exploration into public transport signage typefa- ces. While building on this foundation it incorporates the distinctive characteri- stics of a highly specialized genre to become a versatile grotesque family with a balanced geometrical touch. RT Rondelle embarks on a new life of its own, lea- ving behind the restrictions of its heritage to form a consistent and independent type family. Suited for a wide range of applications www.rt-rondelle.com Supported languages Afrikaans, Albanian, Basque, Bosnian, Breton, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Faroese, Fijian, Finnish, Flemish, French, Frisian, German, Greenlandic, Hawaiian, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Irish, Italian, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Maltese, Maori, Moldavian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Provençal, Romanian, Romany, Sámi (Inari), Sámi (Luli), Sámi (Northern), Sámi (Southern), Samoan, Scottish Gaelic, Slovak, Slovenian, Sorbian, Spa- nish, Swahili, Swedish, Tagalog, Turkish, Welsh File formats Desktop: OTF Web: WOFF2, WOFF App: OTF Available licenses Desktop license Web license App license Further licensing -

Bitten by the Bug Part 1 R J Alliott

• Bitten by The Bug Part 1 R J Alliott Britain’s railway history is littered with a perhaps surprising number of one-offs - the Turbomotive, the Hush-Hush, Fowler’s Ghost, the Duke of Gloucester, and the Great Bear. Many of these remained one-offs because they were partially or wholly unsuccessful, because of subsequent changes of direction in locomotive development or because they were only experimental. However, an unusual example of a one-off that was always intended to be unique from the very outset was the LSWR 4-2-4T known officially as Mr. Drummond’s Car , but known far better by locomen of the time and by enthusiasts ever since as “The Bug”. Drummond himself has also gone down in locomotive engineer folklore as something of a one-off. Born at Ardrossan in 1840, he had served on the Dumbartonshire and Caledonian Railways, and at the North British Railway, where he worked under S. W. Johnson, before moving to the Highland Railway at Inverness under William Stroudley. After a spell with Stroudley again at Brighton, he had become locomotive superintendent of the North British Railway in 1875. Seven years later he joined the Caledonian, but then jointly formed the unsuccessful Australasian Locomotive Engine Works at Sydney. He had then returned quickly to Scotland and founded the Glasgow Railway Engineering Company, finally joining the London and South Western on 1st August 1895 at the very considerable salary of £1,500, this being sharply increased to £2,000 the following year. At the LSWR, he varied between the brilliant and the sadly unsuccessful in his designs and between the severe and compassionate in his dealings with his men and his machines. -

Pupils Look for a Book in Shildon

Issue No 941 At the heart of our wonderful community Friday 11th October 2019 GREEFIELD STUDENTS SHOW ACTS OF KINDNESS STUDENTS OF Greenfield Community College have been reacting positively to a call to action follow- ing their student led con- ference, Make it Matter. Make it Matter is the result of hundreds of stu- dents having a voice and a say about things that matter to them. The successful confer- ence last term created actions for the whole school to try, test and notice their impact. Future initiatives All of the eager children from Timothy Hackworth Primary School and Chair of Governors, Pauline Crook, with the 88 books “will include outside school before heading off to hide them for others to find. practical on- site recycling, PUPILS LOOK FOR A BOOK IN SHILDON Wellbeing ON FRIDAY 4th October, excitement back into work? child by packaging and Wednesday and pupils, governors, teach- reading,” said Year 6 If a parent or their child then hiding books in the random acts ers and parents from Tim- teacher, Jamie Wilcox. finds a book and they like local area. othy Hackworth Primary “The reading initiative the look of it, they can A note should be left for of kindness School went out on an was first started in the take it home to read. the finder explaining that adventure in Shildon to Northumberland area,” They could read it them- once they have read it, to Students created hide books all around the explained Mr Wilcox, “by selves, with an adult or to hide it again. -

On Cycle-To-Cycle Heat Release Variations in a Simulated Spark Ignition Heat Engine

On cycle-to-cycle heat release variations in a simulated spark ignition heat engine P.L. Curto-Risso 1 Departamento de F´ısica Aplicada, Universidad de Salamanca, 37008 Salamanca, Spain A. Medina ∗;2 Departamento de F´ısica Aplicada, Universidad de Salamanca, 37008 Salamanca, Spain A. Calvo Hern´andez 3 Departamento de F´ısica Aplicada, Universidad de Salamanca, 37008 Salamanca, Spain L. Guzm´an-Vargas Unidad Profesional Interdisciplinaria en Ingenier´ıay Tecnolog´ıasAvanzadas, Instituto Polit´ecnico Nacional, Av. IPN No. 2580, L. Ticom´an,M´exico D.F. 07340, M´exico F. Angulo-Brown Departamento de F´ısica, Escuela Superior de F´ısica y Matem´aticas, Instituto Polit´ecnico Nacional, Edif. No. 9 U.P. Zacatenco, M´exico D.F. 07738, M´exico Abstract The cycle-by-cycle variations in heat release for a simulated spark-ignited engine are analyzed within a turbulent combustion model in terms of some basic parameters: the characteristic length of the unburned eddies entrained within the flame front, a arXiv:1005.5410v1 [physics.class-ph] 28 May 2010 characteristic turbulent speed, and the location of the ignition kernel. The evolution of the simulated time series with the fuel-air equivalence ratio, φ, from lean mixtures to over stoichiometric conditions, is examined and compared with previous experi- ments. Fluctuations on the characteristic length of unburned eddies are found to be essential to simulate heat release cycle-to-cycle variations and recover experimental results. Relative to the non-linear analysis of the system, it is remarkable that at fuel ratios around φ ' 0:65, embedding and surrogate procedures show that the dimensionality of the system is small.