Bitten by the Bug Part 1 R J Alliott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRACKS Will Be a Useful Reference

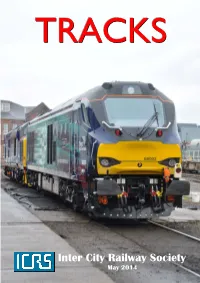

TTRRAACCKKSS Inter City Railway Society May 2014 Inter City Railway Society founded 1973 www.intercityrailwaysociety.org Volume 42 No.5 Issue 497 May 2014 The content of the magazine is the copyright of the Society No part of this magazine may be reproduced without prior permission of the copyright holder President: Simon Mutten (01603 715701) Coppercoin, 12 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4RT Chairman: Carl Watson - [email protected] Mob (07403 040533) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Treasurer: Peter Britcliffe - [email protected] (01429 234180) 9 Voltigeur Drive, Hart, Hartlepool TS27 3BS Membership Sec: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Secretary: Stuart Moore - [email protected] (01603 714735) 64 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4SA Events: Louise Watson - [email protected] Mob (07921 587271) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Magazine: Editor: Trevor Roots - [email protected] details as above Editorial Team: Sightings: James Holloway - [email protected] (0121 744 2351) 246 Longmore Road, Shirley, Solihull B90 3ES Traffic News: John Barton - [email protected] (0121 770 2205) 46, Arbor Way, Chelmsley Wood, Birmingham B37 7LD Website: Manager: Christine Field - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Yahoo Administrator: Steve Revill Books: Publications Manager: Carl Watson - [email protected] details as above Publications Team: Trevor Roots / Carl Watson / Eddie Rathmill / Lee Mason Contents: Officials Contact List ......................................... 2 Stock Changes / Repatriated 92s ......... 44, 47 Society Notice Board ..................................... 2-5 Traffic and Traction News ................... -

2A. Bluebell Railway Education Department

2a. Bluebell Railway Education Department The main parts of a locomotive Based on a Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway locomotive, built in 1925 From the book “Steam Railways Explained”, author Stan Yorke, with permission of Countryside Books BLUEBELL RAILWAY EDUCATION DEPARTMENT 2b. The development of the railway locomotive 1. The steam locomotive is, in essence, a large kettle which heats water until it turns into steam, that steam is then used, under pressure, to move the engine and the train. One of the earliest and most successful locomotives was “The Rocket” used on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which opened in 1830. The Rocket Wheel arrangement 0-2-2 Built 1829 2. This early design was rapidly improved upon and the locomotive soon assumed the shape that we recognise today. “Captain Baxter was built in 1877 and can be seen today at the Bluebell Railway. Dorking Greystone Lime Company No 3 “Captain Baxter” Wheels 0-4-0T Built 1877 3. A the years went by bigger and faster locomotives were developed to meet the needs of both passengers and freight as illustrated by this South Eastern & Chatham Railway engine which ran between London and the Kent coast. South Eastern & Chatham Railway No. 263 Wheel arrangement 0-4-4T Built 1905 4. As passenger traffic grew in the 20th century still larger and more powerful engines were required. This Southern Railway engine, built in 1936, was sent to Barry Scrapyard in South Wales following the end of steam on British Railways in 1968. It was rescued by the Bluebell and delivered to Sheffield Park Station in 1978, where it was restored to running order. -

Memory Lane – Auf Der Straße Der Erinnerung

Memory Lane – Auf der Straße der Erinnerung Ein uraltes blaues Photoalbum erregte meine Aufmerksamkeit in einem walisischen Junk-Shop. Es enthält zahlreiche Photos von Dampflokomotiven, aber auch von Flugzeugen, Hubschraubern und Schiffen, sowie Bahnhöfen, Straßen und Gebäuden. Der unbekannte Photograph nahm sie ab 1951 auf. Besonderes Interesse zeigte er nicht nur an Kirmes- und Garteneisenbahnen, an den großen und kleinen Loks der British Railways, sondern auch an der schmalspurigen Talyllyn Railway in Wales. Spannend war die detektivische Suche nach weiteren Details zu den Lokomotiven und Orten. Eine unschätzbare Hilfe ist mit vielen Informationen die Internetseite http://www.railuk.info/steam/getsteam.php?row_id=23182 . @P. Dr. D. Hörnemann, Eisenbahnmuseum Alter Bahnhof Lette, www.bahnhof-lette.de, Seite 1 von 49 1 Auf die Innenseite des Albumdeckels klebte der unbekannte Photograph sein größtes Bild, die vom schweren Alltagsdienst gezeichnete Güterzuglok der Great Western Railway 3813 mit ihrem Personal. 3813 – GWR 2800 Class 2-8-0 Konstrukteur.................................... Churchward Baujahr ........................................... 30/09/1939 Hersteller ........................................ Swindon Works (GWR/British Railways) Heimatbetriebswerk 1948.................. 83D Plymouth Laira Letzte Beheimatung .......................... 84J Croes Newydd Von der Ausbesserung zurückgestellt .. 31/07/1965 Verschrottet..................................... 31/12/1965 Birds Morriston. @P. Dr. D. Hörnemann, Eisenbahnmuseum Alter Bahnhof Lette, www.bahnhof-lette.de, Seite 2 von 49 2 „Lighter Modes of Travelling“ – „leichtere Transportarten“ nannte der Albumgestalter seine Bilder von der „Emmett Railway“ und der „Battersea Fun Fair“, einer Art Kirmes-Eisenbahn. Die Wagen tragen eine Beschilderung „FTO Railway“ („Far Tottering and Oyster Creek Railway” nach einem Entwurf von Rowland Emmett). Der Battersea Park ist ein 0,83 km² großer Park in Battersea, London. -

'Terrier' Manual

P a g e | 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Features ......................................................................................................................... 4 Background .................................................................................................................... 6 Scenarios ........................................................................................................................ 7 Control Modes ............................................................................................................... 8 Driving Controls ............................................................................................................. 9 Driving in Advanced Mode ........................................................................................... 28 Locomotive Numbering ............................................................................................... 30 Rolling Stock ................................................................................................................. 33 Modification Policy ...................................................................................................... 34 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... 35 Copyright Victory Works 2017, all rights reserved Release Version DTG1.0 P a g e | 3 Introduction Thank you for purchasing the Stroudley -

Honorary President Professor Dugald Cameron OBE

Honorary President Professor Dugald Cameron OBE PACIFIC PROGRESS (photo courtesy www.colourrail.com) We haven’t seen much snow in Surrey in recent years but you can almost feel the chill in this fine view of Merchant Navy No 35005 ‘Canadian Pacific’ approaching Pirbright Junction in the winter of 1963. As mentioned previously in these pages, ‘Can Pac’ was one of 10 Merchant Navy Pacifics to be fitted with North British boilers from new and the loco still carries it in preservation today. At the present time No 35005 is undergoing a thorough overhaul with the NBL boiler at Ropley on the Mid Hants Railway and the frames etc at Eastleigh Works in Hampshire. Mid Hants volunteer John Barrowdale was at Ropley on 15th January and reports that CP’s new inner firebox was having some weld grinding attention before some new weld is added. The boilersmith told him that apart from the welding on the inner wrapper plus a bit on the outer wrapper it is virtually complete with the thermic synthons all fitted in. They hope to be able to drop the inner wrapper into the outer wrapper by the end of March and then the long task of fitting all the 2400 odd stays into the structure beckons plus the fitting of the foundation ring underneath. After work on the boiler is complete it will be sent to Eastleigh to be reunited with the frames and final assembly can begin. There is a long way to go but it shows what can be achieved by a dedicated team of preservationists ! We wish John and his colleagues the very best of luck and look forward to seeing Canadian Pacific in steam again in the years to come. -

Heljan 2020 Catalogue Posted

2020 UK MODEL RAILWAY PRODUCTS www.heljan.dk OO9 GAUGE Welcome …to the 2020 HELJAN UK catalogue. Over the coming pages we’ll introduce you to our superb range of British outline locomotives and rolling stock in OO9, OO and O gauge, covering many classic 6 steam, diesel and electric types. As well as new versions of existing PIN LYNTON & BARNSTAPLE RAILWAY products, we’ve got some exciting new announcements and updates DCC MANNING, WARDLE 2-6-2T READY on a few projects that you’ll see in shops in 2020/21. Class Profile: A trio of 2-6-2T locomotives built VERSION 1 - YEO, EXE & TAW NEM for the 1ft 11½in gauge Lynton & Barnstaple COUPLERS 9953 SR dark green E760 Exe New additions to the range since last year include the Railway in North Devon, joined by a fourth locomotive, Lew, in 1925 and used until the 9955 L&BR green Exe much-requested OO gauge Class 45s and retooled OO Class 47s, the SPRUNG railway closed in 1935. A replica locomotive, BUFFERS 9956 L&BR green Taw GWR ‘Collett Goods’, our updated O gauge Class 31s, 37s and 40s, the Lyd, is based at the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales. ubiquitous Mk1 CCT van and some old favourites such as the O gauge Built by: Manning, Wardle of Leeds VERSION 2 - LEW & LYD Number built: 4 9960 SR green E188 Lew Class 35 and split headcode Class 37. We’re also expanding our rolling Number series: Yeo, Exe & Taw (SR E759-761), stock range with a new family of early Mk2 coaches. -

Southern Railway Locomotive Drawings and Microfilm Lists.Xlsx

Southern Railway Microfilm Lists Description: These are a selection from the Southern Railway Works drawings collection deemed to be of particular interest to researchers and preserved railways. The cards are listed in two tables – a main list of drawings from each of the main works and a smaller list of sketches. There are 943 drawings in total. The main table of drawings has been sub-divided into the three constituent works of the former Southern Railway and British Rail (Southern Region). These were Ashford (formerly the South Eastern & Chatham Railway), Brighton (formerly the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, both B and W series) and Eastleigh (formerly the London & South Western Railway and including the predecessor works at Nine Elms). There are 826 drawings in this series. Details in the tables are drawn directly from the originals. Further information may be obtained by cross-reference with the full list of surviving original drawings (locomotives only) or works registers. A small number of drawings are of poor quality and will not print out in fine detail. This has usually been indicated. Users of these aperture cards are advised that they should view the aperture cards before purchasing printed copies as there can be no guarantee that all details will be clearly visible. The tables as set out include all drawings copied up to the present. The majority are from locomotives, but there are some from carriage and wagons. At all the works these were drawn in the same numerical series. The listing of the original carriage and wagon drawings from the former Southern works is still at an early stage and there may therefore be additions to the available aperture cards in due course. -

Running Day Reports Volume 36. No. 1. February 2008

Volume 36. No. 1. February 2008 Setting up our November display to remember the contribution of LBSC on the 40th anniversary of his death. Running Day Reports with some runs at the full capacity of the cars. I enjoyed run- ning at a nice steady goods train speed time after time up the November 2007 Running Day Report. grade. It made up for the embarrassment of having to retire to This day was hot and humid, there was some high cloud early loco after the first lap to build up the fire with the aid of the but this cleared earlier than we would have liked. As soon as compressed air blower. Teaches one to pay attention to locomo- the cloud cleared the temperature climbed. Our visitors rolled tive preparation and not be distracted. Both locomotives retired in fairly quickly. to loco at about 5.00pm., it was a long afternoon. Bernie was on the gate with the help of a Redkite volunteer as it The ground level running was just the opposite providing the was our Redkite charity day. Shade was at a premium. One best locomotive display for some months. Barry Potter and his group had their own gazebo while another had their own shade friends from Orange were down for the day. Barry had D5507 cover hanging off the foot bridge, even the shady spots on the while Greg and Les Bird came with C3239, as well Roger Ker- pathway were utilised. For I think the first time ever one group shaw acted as spare driver. The 55 and the 32 were out on the had a playpen to keep someone or something contained! track early running one of the outer track trains. -

May 2019 Inter City Railway Society Founded 1973

TTRRAA CCKKSS Inter City Railway Society – May 2019 Inter City Railway Society founded 1973 www.intercityrailwaysociety.org Volume 47 No.4 Issue 552 May 2019 The content of the magazine is the copyright of the Society No part of this magazine may be reproduced without prior permission of the copyright holder President: Simon Mutten - [email protected] (01603 715701) Coppercoin, 12 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4RT Treasurer: Peter Britcliffe - [email protected] (01429 234180) 9 Voltigeur Drive, Hart, Hartlepool TS27 3BS Membership Sec: Colin Pottle - [email protected] (01933 272262) 166 Midland Road, Wellingborough, Northants NN8 1NG Mob (07840 401045) Secretary: Christine Field - [email protected] contact details as below for Trevor Chairman: filled by senior officials as required for meetings Magazine: Editor: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Sightings: James Holloway - [email protected] (0121 744 2351) 246 Longmore Road, Shirley, Solihull B90 3ES Photo Database: Colin Pottle Books: Publications Manager: Trevor Roots - [email protected] Publications Team: Trevor Roots / Eddie Rathmill Website / IT: Website Manager: Trevor Roots - [email protected] contact details as above Social Media: Gareth Patterson Yahoo Administrator: Steve Revill Sales Manager: Christine Field contact details -

CT Crane Tank

CT Crane Tank - a T type loco fitted with load lifting apparatus F Fireless steam locomotive IST Inverted Saddle Tank PT Pannier Tank - side tanks not fastened to the frame ST Saddle Tank STT Saddle Tank with Tender T side Tank or similar - a tank positioned externally and fastened to the frame VB Vertical Boilered locomotive WT Well Tank - a tank located between the frames under the boiler BE Battery powered Electric locomotive BH Battery powered electric locomotive - Hydraulic transmission CA Compressed Air powered locomotive CE Conduit powered Electric locomotive D Diesel locomotive - unknown transmission DC Diesel locomotive - Compressed air transmission DE Diesel locomotive - Electrical transmission DH Diesel locomotive - Hydraulic transmission DM Diesel locomotive - Mechanical transmission F (as a suffix, for example BEF, DMF) – Flameproof (see following paragraph) FE Flywheel Electric locomotive GTE Gas Turbine Electric locomotive P Petrol or Paraffin locomotive - unknown transmission PE Petrol or Paraffin locomotive - Electrical transmission PH Petrol or Paraffin locomotive - Hydraulic transmission PM Petrol or Paraffin locomotive - Mechanical transmission R Railcar - a vehicle primarily designed to carry passengers RE third Rail powered Electric locomotive WE overhead Wire powered Electric locomotive FLAMEPROOF locomotives, usually battery but sometimes diesel powered, are denoted by the addition of the letter F to the wheel arrangement in column three. CYLINDER POSITION is shown in column four for steam locomotives. In each case, a prefix numeral (3, 4, etc) denotes more than the usual two cylinders. IC Inside cylinders OC Outside cylinders VC Vertical cylinders G Geared transmission - suffixed to IC, OC or VC RACK DRIVE. Certain locomotives are fitted with rack-drive equipment to enable them to climb steep inclines; and were mainly developed for underground use in coal mines. -

RCTS Library Book List

RCTS Library Book List Archive and Library Library Book List Column Descriptions Number RCTS Book Number Other Number Previous Library Number Title 1 Main Title of the Book Title 2 Subsiduary Title of the Book Author 1 First named author (Surname first) Author 2 Second named author (Surname first) Author 3 Third named author (Surname first) Publisher Publisher of the book Edition Number of the edition Year Year of Publication ISBN ISBN Number CLASS Classification - see next Tabs for deails of the classification system RCTS_Book_List_Website_09-12-20.xlsx 1 of 199 09/12/2020 RCTS Library Book List Number Title 1 Title 2 Author 1 Author 2 Author 3 Publisher Edition Year ISBN CLASS 351 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of Great Britain as at 31 December 1934 Railway Obs Eds RCTS 1935 L18 353 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of Great Britain as at 31 December 1935 Pollock D R Smith C White D E RCTS 1936 L18 355 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of GB & Ireland as at 31 December 1936 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1937 L18 357 Locomotive Stock Book Appendix 1938 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1938 L18 359 Locomotive Stock Book 1939 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1938 L18 361 Locomotive Stock Alterations 1939-42 RO Editors RCTS 1943 L18 363 Locomotive Stock Book 1946 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Proud Peter RCTS 1946 L18 365 Locomotive Stock Book Appendix 1947 Stock changes only. -

'Knights' of the Southern Lands

ABOVE: No.30772 Sir Percivale makes a move away from ‘KNIGHTS’ OF THE SOUTHERN LANDS Farnborough in 1960. The ‘King Arthurs’, if not sleekly handsome, were certainly purposeful in appearance. The large 5,000-gallon The N15 ‘King Arthur’ Class was the express version of Mr. double bogie tender enhances the suggestion of size and strength. Urie’s two-cylinder 4-6-0 designs for the London & South (Colour-Rail.com 340082) Western Railway on which they were introduced in 1918. After the formation of the Southern Railway at the 1923 BELOW: No.30454 Queen Guinevere briskly works an up South grouping, the new Chief Mechanical Engineer Richard Western main line stopping train, consisting of five Bulleid Maunsell improved the original design in 1925 and vehicles in carmine and cream, past Bramshot in February 1957. added another 54 to make a total of 74. The legendary No.30454 was from the first order for the Southern Railway N15s King Arthur and his knights, ladies and associated which were built at Eastleigh Works in 1925. (Trevor Owen/Colour-Rail.com BRS1973) places became the naming theme for the class (see BT 22/10 for more details) and fine locomotives they were. ABOVE: A very agreeable portrait of No.30805 Sir Constantine during an ‘R BELOW: The signal is ‘off’ for No.30773 Sir Lavaine and R’ break in front of the coaling stage at Ashford shed on 23rd July to depart from Eastleigh station with a service for 1953. Sir Harry was from the final order for N15s delivered from Eastleigh Portsmouth on the evening of 15th August 1961.