Southern Flows: WMD Nonproliferation in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Spotlights 2014

ALUMNI SPOTLIGHTS 2014 A publication of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies Graduates and Participants Course Legend Egresados y Participantes Leyenda del Curso Alumni (Resident course graduates) Egresados (graduados de los cursos presenciales) ADP = Defense Policy (Política de Defensa) CDIM = Curriculum Design and Instructional Methodology Course (Curso de Diseño de Curriculo y Metodologías de Instrucción) CDSC = Caribbean Defense and Security Course (Defensa y Seguridad en el Caribe) CINIS = Cybersecurity: Issues in National and International Security (Ciberseguridad) CPMR = Civ-Pol-Mil Relations and Democratic Leadership (Relaciones Civiles-Militares-Políticas y Liderazgo Democrático) CTOC = Combating Transnational Organized Crime and Illict Networks (Lucha Contra la Delincuencia Organizada Transnacional y las Redes Ilícitas en las Américas) DPRM = Defense Planning and Resource Management (Planificación y Administración de Recursos de Defensa) ECON = Defense Economics and Budgeting (Curso de Economía de Defensa) GGSA = Governance, Governability and Security in the Americas (Gobernanza, Gobernabilidad y Seguridad en las Américas: Respuestas al Crimen Transnacional Organizado) HR/ROL = Strategic Implications of Human Rights and Rule of Law (Implicaciones Estratégicas de los Derechos Humanos y el Estado de Derecho) ICCT = Inter-Agency Coordination and Combating Terrorism (Coordinación Interinstitucional y Combate al Terrorismo) PHSD = Perspectives on Homeland Security and Defense (Perspectivas de Seguridad y Defensa -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 16, Issue 8

Case School of Law Logo War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief Natalie Davis FREDERICK K. COX Volume 16 - Issue 8 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER May 8, 2021 Technical Editor-in-Chief Erica Hudson Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Matthew Pheneger Faculty Advisor Alan Dowling Jim Johnson War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA NORTH AFRICA Libya Azerbaijan Accused Of War Crimes After Execution Of Armenian Prisoners (Morining Star) CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic CAR To Form Commission Of Inquiry To Probe War Crimes – (UN Spokesman) Sudan & South Sudan Haftar blocking Dbeibah visit shows ongoing friction (Daily Sabah) Sudan Suspect Wanted For Darfur Crimes Says ‘Prefers’ ICC Trial (Capital News) Democratic Republic of the Congo Islamic leader slain in east Congo after attacks killing 19 (StarTribune) DR Congo declares state of siege over conflict in east (Anadolu Agency) Congo-Kinshasa: Anti-Monusco Protests Send a Clear Message to Tshisekedi (AllAfrica) WEST -

GRAMSCI La Teoría De La Hegemonía Y Las Transformaciones Políticas Recientes En América Latina Actas Del Simposio Internacional Asunción, 27-28 De Agosto De 2019

GRAMSCI La teoría de la hegemonía Y las transformaciones políticas recientes en América Latina Actas del Simposio Internacional Asunción, 27-28 de Agosto de 2019. CIA EN CI O R P AL N RMI E G AA.VV. Gramsci- La teoría de la hegemonía y las transformacio- nes políticas recientes en América Latina - Actas del Simposio Internacional Asunción, 27-28/8/2019 - 1a edición - Asunción: Centro de Estudios Germinal, 2019. 400 p. ; 15x21 cm – (Colección Germinal Prociencia) ISBN: 978-99967-972-6-2 1- Teoría de la Hegemonía - Siglo XXI. 2. Gramsci. 3. América Latina. CDD 322 © CEEP Germinal Colección Germinal-Prociencia Esta publicación realizada en el marco del Programa PROCIENCIA - Eventos Científicos Y Tecnológicos Emergentes (Proyecto VEVE 19-7), es cofinanciada por el Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología - CONACYT con recursos del FEEI Centro de Estudios y Educación Popular Germinal O›Leary 1143 – Asunción http://germinal.pyglobal.com [email protected] Diseño: Cecilia Rivarola Ilustración de tapa: Carmen López Impreso en Arandurâ Editorial Edición de 1000 ejemplares Queda hecho el depósito que establece la ley ISBN: 978-99967-972-6-2 «La presente publicación ha sido elaborada con el apoyo del CONACYT. El contenido de la misma es responsabilidad exclusiva de los autores y en ningún caso se debe considerar que refleja la opinión del CONACYT». Índice Introducción ..............................................................................7 Marcello Lachi & Raúl Burgos APERTURA Filología y política en la discusión contemporánea de la teoría de la hegemonía ............................................................................ 11 Javier Balsa TEMA 1 Hegemonía y realidad política actual de América Latina Notas sobre la disputa hegemónica y el sentido común en el largo ciclo de impugnación al neoliberalismo en América Latina ........................................................................ -

Descargar Número 847 Completo

847 Nº Boletín FUNDADO EN MAYO del Centro Naval DE 1882 AÑO 136 VOLUMEN CXXXVIAÑO 136 VOLUMEN / ABRIL DE 2018 ENERO BOLETÍN DEL CENTRO NAVAL BOLETÍN DEL CENTRO REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA AÑO 136 - VOL. CXXXVI Nº 847 ENE / ABR DE 2018 REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA Boletín del Centro Naval FUNDADO EN MAYO DE 1882 NÚMERO 847 ENERO / ABRIL DE 2018 Director Capitán de Navío (R) Héctor J. Valsecchi Presidente Consejo Editorial Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Alejandro J. Tierno Vocales Consejo Editorial Imagen de portada: Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Oscar D. Cabral Teniente Eliana Krawczyk. Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Juan J. Membrana FOTOGRAFÍA DE SILVINA ROSSELLO. CORTESÍA DE GACETA MARINERA. ARMADA ARGENTINA Capitán de Navío IM VGM (R) Hugo J. Santillán Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Carlos A. Ares Capitán de Navío (R) Gabriel O. Catolino Miembro de la Asociación de la Prensa Técnica y Especializada Argentina (APTA), desde el 7 de marzo de 1975 Arte y diagramación Guillermo P. Messina Distinciones al Boletín y a quienes en él escriben • Premio APTA/Rizzuto 1989 en la categoría Publicaciones sin fines de lucro Administración y composición • Primer Premio APTA/Rizzuto 1994 en la categoría Publicaciones Oficiales Norma B. González • Premio 1er. Accésit APTA/Rizzuto 1998 en la categoría Publicaciones Oficiales • Reconocimiento al Mérito 2002 Corrección • Reconocimiento a la Trayectoria 2003 Verónica Weinstabl de Iraola • Premio 2do. Accésit APTA/Rizzuto 2004 por Nota de Contenido Técnico • 1er. Premio APTA/Rizzuto 2006 por Nota Científica • Premio 1er. Accésit APTA/Rizzuto 2006 por Nota de Bien Público • Premio 1er. Accésit APTA/Rizzuto 2007 por Nota de Bien Público Florida 801, C1005AAQ Buenos Aires, • Premio 1er. -

Gaceta Universitaria De Derechos Humanos

Gaceta Universitaria de Derechos Humanos Publicación electrónica semanal del Fondo Documental de Derechos Humanos del Sistema de Infotecas Centrales de la Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila Atorado-Cartón de Helioflores 3 Plantearán en Permanente seguridad y plagio de migrantes 4 Pena de muerte: Uno de los mayores crímenes de Estados Unidos 6 Optimista-Cartón de Naranjo 8 De muerte natural- Cartón de Edmundo Gómez 9 ONG's critican el "endurecimiento" de fronteras 10 Trujillo Flores exhorta a vigilar derechos humanos 11 Abren Centro de Derechos Humanos en Berna 12 Aplausos- Cartón de Jabaz 15 Seis ciudades andaluzas reclaman la protección de los derechos humanos en los países del 16 Norte de África en conflicto Cadena perpetua para el asesino de un abogado ruso y una periodista 18 El CELS presentó su informe anual sobre derechos humanos 19 CNDH investiga explosión en pozo de Coahuila 20 Taty Almeida: "La SIP ataca a la democracia y a los derechos humanos" 21 Siria: Cinco muertos por tiros en Homs (Activistas DDHH) 22 China expresa su deseo de mantener un diálogo con EEUU en materia de DDHH 23 Oposición: politización de justicia incluso vulnera derechos humanos 24 Sólo por quejas ciudadanas podría intervenir la CEDH 26 Comisión inter-sectorial para Derechos Humanos traza líneas de actuación 28 Presidente de la comisión de Derechos Humanos refuta a Larroulet por voto chileno en el 29 exterior “No es admitible amnistía o indulto para casos de violaciones de DDHH” 30 Acreditan omisión de agente ministerial tras muerte de un menor atropellado -

Med Menneske– Rettar Som Forkleding

MED MENNESKE– RETTAR SOM FORKLEDING Oslo Freedom Forum sine gjestar frå Latin-Amerika 2009-2014 Rapporten er utgitt av Latin-Amerikagruppene i Norge (LAG) 2014 Støttet av Norad Rapporten kan også lastes ned på www.lagnorge.no Layout: Jon Arne Berg Trykk: 07 Latin-Amerikagruppene i Norge Med menneskerettar som forkleding Med menneskerettar som forkledning Latin-Amerikagruppene i Norge har sett Oslo Freedom Forum (OFF) i eit kri- International Norge, LIM og den Norske Helsinki Komité utgjer dei forei- tisk søkeljos sidan forumet vart etablert og arrangert for fyrste gong i 2009. ninga Oslo Freedom Forum. At Civita som høgresida sin tenketank inviterar Kvar vår er Oslo vertsby for forumet som er presentert som ein møteplass profilerte politikarar frå den latinamerikanske høgresida til Noreg er open- for menneskerettsheltar, ein stad å setje fokus på menneskerettane ved å bart. Men å profilere forumet som ei samling for menneskerettsforkjempa- setje stas på kvinner og menn verda over som har gjort ein spesiell innsats. rar, er etter LAG si meining ei suspekt tildekking av eit arrangement med ein LAG ynskjer eit internasjonalt menneskerettsforum velkommen, men stil- klar høgrepolitisk agenda. ler seg imidlertid veldig kritisk til dei personane som vert invitert frå La- LAG er vel vitande om at enkelte personar som har gjesta forumet opp tin-Amerika. Ein stor del av gjestene frå Latin-Amerika har markera seg som gjennom åra, har gjort ein skikkeleg innsats for mennesekerettar. Vår kritikk undertrykkerar snarare enn forkjemparar av menneskerettane, og enkelte går derfor ikkje til deltakarane. Men å kalle kuppmakarar og statsoverhode av gjestene som er inviterte som menneskerettsheltar er kuppmakarar. -

ILR Consolidated Table of Cases

CONSOLIDATED TABLE OF CASES ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY VOLUMES 1—125 Notes : This table of cases lists as comprehensively as possible, in alphabetical order, all cases reproduced or reported in the Annual Digest /International Law Reports, entering cases under all common variants of their title. It should be noted that many cases appearing in the AD/ILR do not have a title as such in their original version (e.g. in jurisdictions where the practice is to use case numbers rather than titles). There are other circumstances (e.g. ICJ cases) where to include the full formal title (including the introductory ‘Case concerning’) would be misleading in an alphabetical table. Such cases are listed under the key element[s] (e.g. ‘Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955’ rather than ‘Case concerning ...’). The full formal titles are used, where they exist, in the table of cases by jurisdiction. ILR practice, in the presentation of cases and in the treatment of cases referred to and in the matter of cross-references, has varied considerably over the years. So far as practicable, the current table brings earlier tables into conformity with current practice. Page references in earlier tables have accordingly been deleted where they contained no more than a cross- reference or a direction to another part of the volume where treatment of the case could be found. Where, in the Annual Digest in particular, a long extract from a case has been included, this has been treated as a full report rather than a note – ‘long’, of course, being a variable concept. Current ILR practice is, wherever appropriate, to use English in case titles (e.g. -

The Perpetrator As Citizen

The Perpetrator as Citizen Self-identification from National Hero to Victimised Subject Utrecht University Thesis RMA History Student: Francesca Hooft Student number: 5701422 Supervisor: dr. Uğur Ümit Üngör Second reader: dr. Geraldien von Frijtag Drabbe Kunzel Date: 23th of June 2017 Contents Introduction 3 Post-conflict dynamics and perpetrator narratives 10 Memory and narrative 10 Perpetrator narratives 12 Citizenship and power 16 Methodological framework 20 Argentina 24 Interpreting the past: memory and narrative 24 Framing the past, presenting the self 29 Perpetrators in society 46 Rwanda 52 Memory and narrative 52 Framing the past, presenting the self 57 Perpetrators in society 77 Conclusion 82 Sources 88 Literature 92 Appendix I 96 Appendix II 104 2 Introduction “I never tortured, it was not my job. But if they had asked me to torture, sure I would have. The Navy taught me to destroy. They did not teach me how to build, they taught me how to destroy. I know how to put mines and bombs, I know how to infiltrate, I know how to disarm an organization, I know how to kill. All that I know, I do well. I always say: I am crude, but I had a single act of lucidity in my life: that was to get into the Navy”. 1 Alfredo Astiz. “The crowd had grown. I seized the machete, I struck a first blow. When I saw the blood bubble up, I jumped back a step. Someone blocked me from behind and shoved me forward by both elbows. I closed my eyes and I delivered a second blow like the first. -

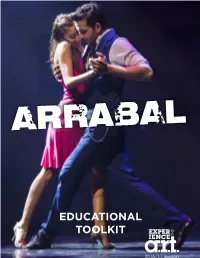

Toolkit Arrabal Toolkit

EDUCATIONAL TOOLKIT 2016/17 Season Photo: Evgnia Eliseeva Evgnia Photo: Welcome! This Toolkit includes materials collected to deepen engagement with the artists, music, dance style, and historical context behind the A.R.T. production of Arrabal. A new tango-infused dance theater piece, Arrabal follows one woman’s quest to understand the violence that took her father and disrupted a nation. Told through dance and propulsive music, Arrabal invites audiences into the underground world of Buenos Aires’ tango clubs for a dance between the present and the past. The materials included here are selected, organized, and contextualized for ease of use in a classroom setting and for personal enrichment in preparation or as a follow-up to attending the A.R.T. production of Arrabal. See you at the theater! BRENNA NICELY DANIEL BEGIN Education & Community Education & Community Programs Manager Programs Fellow @americanrep #ArrabalART Table of Contents Arrabal and the A.R.T. A Tango with the Past.............................................................................................................5-7 Meet the Artists of Arrabal.................................................................................................8-10 Thank you for participating Sergio Trujillo Talks About Arrabal................................................................................11-12 in the A.R.T. Education Gustavo Santaolalla Puts Argentina’s History in Arrabal Music........................13-15 Experience! Arrabal Synopsis........................................................................................................................16 -

Full Issue 5.2

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 1 August 2010 Full Issue 5.2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2010) "Full Issue 5.2," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 5: Iss. 2: Article 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol5/iss2/1 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors’ Introduction This special section focuses on genocide and related mass violence in Latin America. Clearly there is a long history of genocide of indigenous peoples, from the arrival of Columbus and other conquerors to the present day. Perpetrated first by European colonial powers, particularly Spain and Portugal, genocidal activities continued in postcolonial settler states following the revolutions of the nineteenth century. Government shifted from Europe to local Euro-American, as well as in some cases indigenous, elites, who shared economic and thus political power with imperialist international actors—including, in many cases, the United States and some of its large corporations. Human-rights abuses continued. In the second half of the twentieth century, the Cold War–era National Security Doctrine, as well as state- specific tensions and agendas, played out in various Latin American contexts in a new round of repression, genocide, and other forms of mass violence. The Guate- malan Genocide of the 1980s and systematic killings and general military repression under dictatorships in Chile and Argentina in the 1970s and 1980s are perhaps the best-known cases, but others abound. -

Health and Human Rights

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Human Rights and Health Introduction by Paul Hunt U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health and Professor of Law, University of Essex, UK Over fifty years ago, the constitution of the World Health Organization recognized the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental human right. Since then, the right to the highest attainable standard of health (“right to health”) has been enshrined in a series of international and regional human rights treaties, as well as in over 100 constitutions worldwide. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights includes as a central provision the right to health in international human rights law: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” (article 12). International treaties also recognize a range of other human rights of central relevance to health, including the rights to adequate shelter, food, education, privacy, non-discrimination and the prohibition against torture. There are a variety of links between health and human rights: Violations of, or inattention to, human rights can have serious consequences for health; Health policies and programs can either promote or violate human rights in the way that they are designed or implemented; Vulnerability and the impact of ill-health can be reduced by taking steps to respect, protect and fulfill human rights. Human rights are relevant to a great many health issues, including prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS; sexual and reproductive health; access to clean water and adequate sanitation; medical confidentiality; access to education and information on health; access to drugs; and the health of marginalized and vulnerable groups such as women, ethnic and racial minorities, refugees and people with disabilities. -

Gramsci, La Teoría De La Hegemonía Y Las Transformaciones Políticas

LOS AUTORES: COLECCIÓN GERMINAL-PROCIENCIA .VV. Edición a cargo de: AA Una colección de El Simposio Internacional Gramsci, la teoría de la hegemonía investigaciones, ensayos y Marcello Lachi y las transformaciones políticas recientes en América Latina actas de eventos realizados Raúl Burgos ha permitido debatir sobre la vigencia y la fuerza heurística en el marco del programa de la teoría gramsciana aplicada a diferentes contextos PROCIENCIA de CONACYT. sociopolíticos latinoamericanos, tanto a nivel nacional como regional. El debate ha movilizado las categorías de la teoría Han colaborado: de la hegemonía para pensar tanto cuestiones referentes Javier Balsa a la propia teoría, como los procesos de transformaciones políticas desencadenados en la región en las primeras atina Mabel Thwaites Rey décadas del siglo XXI. L Hernán Ouviña Este abordaje ofreció un telón de fondo extremamente Títulos publicados en esta colección: Miguel Angel Herrera Zgaib productivo para los debates. Al respecto, describiendo mérica a Antonio Gramsci y su obra, el historiador inglés Eric A AA.VV. Alma Monges, 100 AÑOS DE GOLPES Hobsbawn ha afirmado: “su estatura como pensador Y REVOLUCIONES Charles Quevedo marxista original – en mi opinión, el pensamiento más Actas del Simposio Internacional Raúl Burgos original surgido en occidente desde 1917– es reconocida, se Asunción, 12-13/12/2017. puede decir, por consenso”. En efecto, el pensamiento de Marcos Del Roio Gramsci ha influenciado prácticamente todas las esferas de Marcello Lachi Marcello Lachi la teoría social,