The Spirituality of Anorexia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fad Diet Or Exercise? Maintainaing Weight Among Millennials

FAD DIET OR EXERCISE? MAINTAINAING WEIGHT AMONG MILLENNIALS by Leigh Mattson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Nutritional Sciences Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 7, 2018 Texas Christian University, Leigh Mattson, May 2018 FAD DIETS OR EXERCISE? MAINTAINING WEIGHT AMONG MILLENNIALS Project Approved: Supervising Professor: Dr. Anne VanBeber, PhD, RD, LD, FAND Department of Nutritional Sciences Dr. Lyn Dart, PhD, RD, LD Department of Nutritional Sciences Dr. Wendy Williams John V. Roach Honors College 2 Texas Christian University, Leigh Mattson, May 2018 ABSTRACT Background: Research indicates millennials are more concerned about having healthy eating habits than following fad diets, and they exercise more than their baby boomer counterparts. The purposes of this study were 1) to determine reasons university students follow fad diets, and 2) to determine other methods students utilize for weight management. Methods: In this un-blinded, randomized trial approved by TCU IRB, participants completed an online research questionnaire after providing informed consent. Population included 236 TCU male and female students, 18-22 years old. Analyses assessed students’ history of fad dieting and outcomes, perceived health status based on body weight and image, eating and exercise habits, and incidence of lifestyle practices such as smoking and alcohol use. Data was analyzed using SPSS (p<0.05). Frequency distributions and correlations were analyzed for trends in health maintenance behaviors. Results: Participants self-identified as 76% females, 85% white, 6% Hispanic, and 4% other ethnicity. Only 32% of participants had followed a fad diet (p=0.01). Participants who followed fad diets included 30% Paleolithic®, 23% Gluten-Free®, 20% Weight Watchers®, and 14% Atkins®. -

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

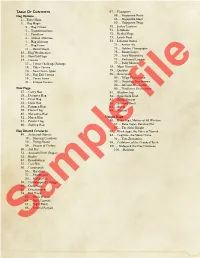

Table of Contents 67

Table Of Contents 67 . Hagspawn Hag Options 68 . Hagspawn Brute 2 . Elder Hags 68 . Hagspawn Mage 3 . Hag Magic 69 . Hagspawn Thug 3 . Hag Curses 70 . Jack o' Lantern 4 . Transformations 71 . Jermlaine 4 . Familiars 72 . Kenku Mage 4 . Animal Affinities 73 . Leech Toad 4 . Hag Alchemy 74 . Libation Oozes 7 . Hag Items 74 . Amber Ale 11 . Weird Magic 75 . Golden Champagne 15 . Hag Weaknesses 75 . Ebony Lager 16 . Non-Evil Hags 75 . Ivory Moonshine 17 . Covens 77 . Perfumed Liqueur 17 . Coven Challenge Ratings 77 . Ruby Merlot 18 . Elder Covens 78 . Moor Hound 18 . New Coven Types 79 . Quablyn 19 . Non-Evil Covens 80 . Scarecrow 19 . Coven Items 80 . Effigy Scarecrows 21 . Unique Covens 80 . Guardian Scarecrows 80 . Infernal Scarecrow New Hags 80 . Pestilence Scarecrows 27 . Carey Hag 81 . Shadow Asp 29 . Deemves Hag 82 . Sporeback Toad 31 . Deep Hag 82 . Stirge Swarm 33 . Dusk Hag 83 . Stitched Devil 35 . Fanggen Hag 84 . Styrix 38 . Hocus Hag 85 . Wastrel 40 . Marzanna Hag 42 . Mojan Hag Unique Hags 44 . Powler Hag 86 . Baba Yaga, Mother of All Witches 46 . Sighing Hag 87 . Baba Yaga's Dancing Hut 87 . The Solar Knight Hag Related Creatures 90 . Black Agga, the Voice of Vaprak 49 . Animated Objects 93 . Cegilune, the Moon Crone 49 . Dancing Cauldron 96 . Yaya Zhelamiss 50 . Flying Spoon 98 . Ceithlenn, of the Crooked Teeth 50 . Swarm of Cutlery 101 . Malagard, the Hag Countess 50 . Ash Rat 106 . Kalabon 52 . Assassin Devil (Dogai) 53 . Boglin 54 . Broodswarm 55 . Cait Sith 56 . Canomorph 56 . Haraknin 57 . Shadurakul 58 . Yeshbavhan 59 . Catobleopas Harbinger 60 . -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 102, No. 11

a c/> c/> The most famous names in American men's wear are here for you: Eagle, Society Brand, GGG, Hickey-Freeman, Burberry, Alligator, 'Botany' 500, Alpagora, Arrow, Hathaway, Swank, McGregor, Bemhard Altmann, Dobbs, Florsheim . and many, many more. Truly the finest men's clothing and furnishings ob tainable in today's world markets. On the Cmnfius—Notre Drnne o &&& ... so select what you need now: a new suit or topcoat for the holidays ahead . gifts for special friends, and charge them the Campus Shop way. By the way, the Campus Shop will give you quick, expert fitting service so that what you purchase now will be altered and ready before. you leave the campus for the holidays. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! CHARGE IT THE CAMPUS SHOP WAY 1/3 1/3 IN JUNE IN JULY No Carrying Charge ^ILBERrS On the Campus—Notre Dune Kttfa QaCampis MsShoIman (Author of "I Was a Teen-age Dwarf", "The Manii Loves of Dobie Gillis", etc.) DECK THE HALLS The time has come to make out our Robespierre, alas, was murdered quicker Inarticulate Society Christmas shopping lists, for Christmas than 3'ou could shout Jacques Robes Editor: %\-iU be upon us quicker than you can saj' pierre (or Jack Robinson as he is called Mr. Hudson, in last w^eek's Reper cussions, took issue with Mr. Smith's Jack Robinson. (Have j'ou ever won in the English-speaking countries). hierarchical theory of government: it dered, incidentall}--, about the origin of (There is, I am pleased to report, one was Mr. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions. -

Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-14-2014 Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14110747 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Mitchell, Michelle, "Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida SURVIVING AND THRIVING IN A HOSTILE RELIGIOUS CULTURE: CASE STUDY OF A GARDNERIAN WICCAN COMMUNITY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Michelle Irene Mitchell 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Michelle Irene Mitchell, and entitled Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture: Case Study of a Gardnerian Wiccan Community, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Lesley Northup _______________________________________ Dennis Wiedman _______________________________________ Whitney A. Bauman, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 14, 2014 The thesis of Michelle Irene Mitchell is approved. -

De-Demonising the Old Testament

De-Demonising the Old Testament An Investigation of Azazel , Lilith , Deber , Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible Judit M. Blair Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I declare that the present thesis has been composed by me, that it represents my own research, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. ______________________ Judit M. Blair ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank and acknowledge for their support and help over the past years. Firstly I would like to thank the School of Divinity for the scholarship and the opportunity they provided me in being able to do this PhD. I would like to thank my ‘numerous’ supervisors who have given of their time, energy and knowledge in making this thesis possible: To Professor Hans Barstad for his patience, advice and guiding hand, in particular for his ‘adopting’ me as his own. For his understanding and help with German I am most grateful. To Dr Peter Hayman for giving of his own time to help me in learning Hebrew, then accepting me to study for a PhD, and in particular for his attention to detail. To Professor Nick Wyatt who supervised my Masters and PhD before his retirement for his advice and support. I would also like to thank the staff at New College Library for their assistance at all times, and Dr Jessie Paterson and Bronwen Currie for computer support. My fellow colleagues have provided feedback and helpful criticism and I would especially like to thank all members of HOTS-lite I have known over the years. -

The Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram (LBRP) Class with Jane Pierce ([email protected])

The Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram (LBRP) Class with Jane Pierce ([email protected]) Qabalistic Cross 1. Standing in the center, facing East draw a line from above your head to your forehead and vibrate “A TAH.” (T hou art) 2. Continue drawing the line down below your feet and vibrate “ MALKUTH .” ( the Kingdom ) 3. Touch your breastbone with your right hand drawing a line as you extend your arm and vibrate “ VEGEVURAH .” ( the Power ) 4. Touch your breastbone with your left hand drawing a line as you extend your arm and vibrate “ VEGEDULAH .” ( the Glory ) 5. Bring both together, fingers up, in front of your breastbone and vibrate “ LEOLAM, AMEN .” (f orever, Amen. ) Sealing the Circle 6. Go to East, draw pentagram, point to center and vibrate “ YUD HEH VEV HEH. ” 7. Begin drawing the circle, stop in the south, draw a pentagram, point to the center and vibrate “ ADONAI.” 8. Continue drawing the circle, stop in the west, draw a pentagram, point to the center and vibrate “ EHHEYEH. ” 9. Continue drawing the circle, stop in the north, draw a pentagram, point to the center and vibrate “ AHGELAH .” 10. Complete drawing the circle to the place you started in the East. Return to the center. Invoking the Archangels 11. Face East and vibrate “ Before me, RAPHAEL. ” (Visualize him carrying a Caduceus.) 12. Vibrate “B ehind me, GABRIEL .” (Visualize her carrying a chalice.) 13. Vibrate “O n my right, MICHAEL. ” (Visualize him carrying a flaming sword.) 14. Vibrate “O n my left, URIEL .” (Visualize her carrying a living branch.) 15. -

BE Aware of the Threefold Law with This Kind of Spell!

Love Spells (BE aware of the threefold law with this kind of spell!) To obtain the love from a specific person At nighttime light a small fire in a cauldron or what ever you have available to contain the fire. Cut out a piece of paper that is 3 inches by 3 inches. Draw a heart on it and color it in with red. Write the name of the name of the person that you desire on the heart. While doing all this be thinking of this person being attracted to you and not being able to resist you! Think of his or her heart burning with desire for you just like the flames of the fire. Then kiss the name on the heart 3 times. Place the paper in the fire while saying these words 3 times. Do so with sincerity... "Fire come from below, bring me love that I do know, make my heart blaze and shine, to bring the love that will be mine!" Soon my love will come a day, three times strong and here to stay!" "SO MOTE IT BE!" Stay and meditate on the spell you just did, seeing it come true! After you are finished concentrating for a few minutes, extinguish the fire. Soon your love will come to you! Soulmate Dream Ritual Items: 3 almonds and 3 raisins - Milk - Honey Ritual: Put the almonds and raisins under your pillow. Before you go to bed, drink a cup of warm milk with a tsp. of honey then go to sleep. If you wonder if a certain person is your soulmate (“the” one) it will tell you in your dream. -

A Short Course in Scrying

A Short Course in Scrying Benjamin Rowe copyright 1997, 1998 Introduction This paper was written in response to requests by participants of the “enochian-l” and “Praxis” internet discussion groups; it first appeared as a series of posts on those groups in early 1997. The current version has been slightly rewritten to enhance the clarity of the presentation, and to include a small amount of additional material. The techniques described herein are adaptations of techniques I learned from two sources. The first of these is Mr. Brian D., who taught me the basic method many years ago. The second is Mr. Paul Solomon and his group, the Fellowship of the Inner Light, who had transformed that method into the foundation of their system of spiritual work. Special thanks also to the “secret chiefs” of the Fellowship, for their direct and effective contribution to my work at a critical point. Some debts can never be repaid; the best that can be done is to pass on what was given. ïL Chapter 1. Preliminary Considerations To begin, the reader should understand that scrying is as much a learned skill as is reading or ice-skating. Persistent practice is necessary to teach the nervous system how to do it, even where the person has some innate talent. And as with other learned skills, there is a learning curve. At first there will be a long period when you don't seem to be making any significant progress. Then things will suddenly fall together and your practice will improve markedly in a short period, before leveling off again at something close to your highest level of skill. -

Healers of Our Time: Women, Faith, and Justice a Mapping Report

HEALERS OF OUR TIME: WOMEN, FAITH, AND JUSTICE A MAPPING REPORT Conducted by The Institute for Women’s Policy Research Supplemented by Women in Theology and Ministry Candler School of Theology, Emory University October 2008 The Sister Fund Copyright 2008 tsf-cover-spine-spread.indd 2 11/18/08 8:54:22 AM The Sister Fund ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many individuals contributed to the produc- Professor and Director of Women in Theology tion of this study. At The Sister Fund, Dr. Helen and Ministry, and Hellena Moon, doctoral student LaKelly Hunt, President, and Kanyere Eaton, in the Graduate Division of Religion, the research Executive Director, conceived of the project and team extended the original pool of women’s planned its original content and design. Lilyane organizations and expanded the academic Glamben, former Deputy Director, served as research review. They also revised and edited the project director. Julia A. Cato, Program Officer, original report. Team members included Michelle and Linda Kay Klein, Director of Research and Hall, Ayanna Abi-Kyles, Josey Bridges, and Anne Communications, were invaluable members of Hardison-Moody. the project team. Lake Research Partners and Auburn Media The original study was conducted by the provided helpful review of the content and the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR). project as a whole. Elizabeth Perrachione served Dr. Amy Caiazza, former Director of Democracy as editor, with assistance from Leslie Srajek. The and Society Programs, served as primary Sister Fund hosted two separate sessions, May researcher and author. Anna Danziger, Mariam 10, 2007, and February 27, 2008, at which a K. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction,