Thesis 19 Apr 37651154

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton's Forgotten Epidemics

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics / D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-9782417-4-2 Print catalogue data is available from Library and Archives Canada, at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca Cover Image: Historical City of Hamilton. Published by Rice & Duncan in 1859, drawn by G. Rice. http://map.hamilton.ca/old hamilton.jpg Cover Design: Robert Huang Group Photo: Temara Brown Ch2olera Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Contents FIGURES AND TABLES vii Introduction Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles 2 2 “From Time Immemorial”: British Imperialism and Cholera in India Diedre Beintema 8 3 Miasma Theory and Medical Paradigms: Shift Happens? Ayla Mykytey 18 4 ‘A Rose by Any Other Name’: Types of Cholera in the 19th Century Thomas Siek 24 5 Doesn’t Anyone Care About the Children? Katlyn Ferrusi 32 6 Changing Waves: The Epidemics of 1832 and 1854 Brianna K. Johns 42 7 Charcoal, Lard, and Maple Sugar: Treating Cholera in the 19th Century S. Lawrence-Nametka 52 iii 8 How Disease Instills Fear into a Population Jacqueline Le 62 9 The Blame Game Andrew Turner 72 10 Virulence Victims in Victorian Hamilton Jodi E. Smillie 80 11 On the Edge of Death: Cholera’s Impact on Surrounding Towns and Hamlets Mackenzie Armstrong 90 12 Avoid Cholera: Practice Cleanliness and Temperance Karolina Grzeszczuk 100 13 New Rules to Battle the Cholera Outbreak Alexandra Saly 108 14 Sanitation in Early Hamilton Nathan G. -

Miasma Vs Germ Theory Nina Kokayeff College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 10 Article 24 4-1-2012 Dying to be Discovered: Miasma vs Germ Theory Nina Kokayeff College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Kokayeff, Nina (2013) "Dying to be Discovered: Miasma vs Germ Theory," ESSAI: Vol. 10, Article 24. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol10/iss1/24 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kokayeff: Dying to be Discovered: Miasma vs Germ Theory Dying to be Discovered: Miasma vs Germ Theory by Nina Kokayeff (Chemistry 1551) n 1832, Mozart‘s librettist Lorenzo da Ponte arranged for the visit of an Italian opera troupe to cholera-stricken Manhattan. They arrived to find the streets empty and silent except for ―I the ringing of church bells and the rattle of carts taking corpses to graveyards. Every resident who could had fled…‖ (Karlen, 1995). The cholera outbreak across many countries in the 19th century was the last of the great pandemics in which the miasma theory about the origin of disease was considered. New practices were developed to reduce the spread of the disease and a new picture of disease transmission emerged. The efficacy of these measures inspired other countries to follow suit, and soon encouraged some of the most groundbreaking biomedical research in history. Miasma Theory of disease contagion was popular for centuries in Western cultures. -

V Sir Ronald Ross and the Significance of His Work

V SIR RONALD ROSS AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HIS WORK T WAS my pleasure in January, 1927, to be present at the I unveiling of a bronze tablet on a gateway in front of the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta, leading to the un- pretentious little brick building in the hospital compound which Sir Ronald Ross used as a laboratory twenty-nine years earlier. That spot deserves to rank among the first in the world in historic interest, yet I had lived in Calcutta for almost three years and had passed that very gateway hun- dreds of times, without knowing of its existence. In an ad- dress made at the time, Colonel Megaw, then Director of the School of Tropical Medicine in Calcutta, remarked that it was astonishing that so few of the inhabitants of Calcutta knew of the existence of the little laboratory where one of the greatest discoveries in the history of the world was made. He added that although over twenty-eight years had passed, we had only begun to scratch the surface of the vast mine of wealth which that discovery had placed in our hands. “A prophet,” said Col. Megaw, “is not without honor save in his own country. Sir Ronald’s offense did not consist merely in being a prophet; he added to it by being a poet and a scientist, and so trebly earned the indifference with which his great work was received in India.” This same Sir Ronald Ross, at the age of seventy-five, died at his modest home in Putney, England, barely six months ago. -

Sagar-XIX.Pdf

Editorial Board Ishan Chakrabarti – Co-Editor-in-Chief, The University of Texas at Austin Matthew D. Milligan – Co-Editor-in-Chief, The University of Texas at Austin Dan Rudmann – Co-Editor-in-Chief, The University of Texas at Austin Kaitlin Althen – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Reed Burman – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Christian Current – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Cary Curtis – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Christopher Holland – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Priya Nelson – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Natasha Raheja – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Keely Sutton – Editor, The University of Texas at Austin Faculty Advisor Syed Akbar Hyder, Department of Asian Studies Editorial Advisory Board Richard Barnett, The University of Virginia Manu Bhagavan, Hunter College-CUNY Nandi Bhatia, The University of Western Ontario Purnima Bose, Indiana University Raza Mir, Monmouth University Gyan Prakash, Princeton University Paula Richman, Oberlin College Eleanor Zelliot, Carleton College The University of Texas Editorial Advisory Board Kamran Ali, Department of Anthropology James Brow, Department of Anthropology Barbara Harlow, Department of English Janice Leoshko, Department of Art and Art History W. Roger Louis, Department of History Gail Minault, Department of History Veena Naregal, Department of Radio-Television-Film Sharmila Rudrappa, Department of Sociology Martha Selby, Department of Asian Studies Kamala Visweswaran, Department of Anthropology SAGAR A SOUTH ASIA GRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL Sponsored by South Asia Institute Itty Abraham, Director The University of Texas at Austin Volume 19, Spring 2010 Sagar is published biannually in the fall and spring of each year. -

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z Name Arrival date Biographical details Macartney (nee McGowan), Fanny B. 13.02.1841 in Ireland. D. 23.02.1873 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Occupation: Home Duties. Macartney, John B. 11.07.1840 in Ireland. D. 19.03.1927 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Lived at Flint St, Nth Ipswich. Occupation: Engine Driver for QLD Government Railways. MacDonald, Robina 1865 (Drayton) B. 03.03.1865. D. 27.12.1947. Occupation: Seamstress. Married Alexander 1867 (Ipswich) approx. Fairweather. MacDonald (nee Barclay), Robina 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 1834. D. 27.12.1908. Married to William MacDonald. Lived in Canning Street, 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) North Ipswich. Occupation: Housewife. MacDonald, William 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 13.04.1837. D. 26.11.1913. William lived in Canning Street, North Ipswich. 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) Occupation: Blacksmith. MacFarlane, John 1862 (Australia) B. 1829. John established a drapery business in Ipswich. He was an Alderman of Ipswich City Council in 1873-1875, 1877-1878; Mayor of Ipswich in 1876; a member of Parliament from 1877-1894; a member of a group who established the Woollen Mill in 1875 of which he became a Director; and a member of the Ipswich Hospital Board. John MacFarlane lived at 1 Deebing Street, Denmark Hill and built a house on the corner of Waghorn and Chelmsford Avenue, Denmark Hill. -

Colonial Medicine and Imperial Authority in JG Farrell's the Siege

J Med Humanit DOI 10.1007/s10912-014-9313-5 ‘AGreatBeneficialDisease’: Colonial Medicine and Imperial Authority in J.G. Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur Sam Goodman # The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article examines J. G. Farrell’s depictions of colonial medicine as a means of analysing the historical reception of the further past and argues that the end-of-Empire context of the 1970s in which Farrell was writing informed his reappraisal of Imperial authority with particular regard to the limits of medical knowledge and treatment. The article illustrates how in The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), Farrell repeatedly sought to challenge the authority of medical and colonial history by making direct use of period material in the construction of his fictional narrative; by using these sources with deliberate critical intent, Farrell directly engages with the received historical narrative of colonial India, that the British presence brought progress and development, particularly in matters relating to medicine and health. To support these assertions the paper examines how Farrell employed primary sources and period medical practices such as the nineteenth-century debate between miasma and water- borne Cholera transmission and the popularity of phrenology within his novels in order to cast doubt over and interrogate the British right to rule. Overall the paper will argue that Farrell’s critique of colonial medical practices, apparently based on science and reason, was shaped by the political context of the 1970s and used to question the wider moral position of Empire throughout his fiction. -

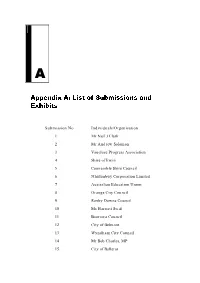

Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits

A Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits Submission No Individuals/Organisation 1 Mr Neil J Clark 2 Mr Andrew Solomon 3 Vaucluse Progress Association 4 Shire of Irwin 5 Coonamble Shire Council 6 Nhulunbuy Corporation Limited 7 Australian Education Union 8 Orange City Council 9 Roxby Downs Council 10 Ms Harriett Swift 11 Boorowa Council 12 City of Belmont 13 Wyndham City Council 14 Mr Bob Charles, MP 15 City of Ballarat 148 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT 16 Hurstville City Council 17 District Council of Ceduna 18 Mr Ian Bowie 19 Crookwell Shire Council 20 Crookwell Shire Council (Supplementary) 21 Councillor Peter Dowling, Redland Shire Council 22 Mr John Black 23 Mr Ray Hunt 24 Mosman Municipal Council 25 Councillor Murray Elliott, Redland Shire Council 26 Riddoch Ward Community Consultative Committee 27 Guyra Shire Council 28 Gundagai Shire Council 29 Ms Judith Melville 30 Narrandera Shire Council 31 Horsham Rural City Council 32 Mr E. S. Cossart 33 Shire of Gnowangerup 34 Armidale Dumaresq Council 35 Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales 36 City of Glen Eira 37 District Council of Ceduna (Supplementary) 38 Mr Geoffrey Burke 39 Corowa Shire Council 40 Hay Shire Council 41 District Council of Tumby Bay APPENDIX A: LIST OF SUBMISSIONS AND EXHIBITS 149 42 Dalby Town Council 43 District Council of Karoonda East Murray 44 Moonee Valley City Council 45 City of Cockburn 46 Northern Rivers Regional Organisations of Councils 47 Brisbane City Council 48 City of Perth 49 Shire of Chapman Valley 50 Tiwi Islands Local Government 51 Murray Shire Council 52 The Nicol Group 53 Greater Shepparton City Council 54 Manningham City Council 55 Pittwater Council 56 The Tweed Group 57 Nambucca Shire Council 58 Shire of Gingin 59 Shire of Laverton Council 60 Berrigan Shire Council 61 Bathurst City Council 62 Richmond-Tweed Regional Library 63 Surf Coast Shire Council 64 Shire of Campaspe 65 Scarborough & Districts Progress Association Inc. -

Medieval Medicine Medical Renaissance

Medieval England 1250-1500 1500-1700 Medical 18th and 19th Century Religion not Science Renaissance Britain Supernatural Ideas Enquiring Attitudes Science and Tech God sends disease as a punishment Continuity: Supernatural explanations - God Continuity: Although the same rational The position of the planets had an impact and Planets - became less popular. Rational explanations for disease were around the Theory on health explanations were more favoured - New - of the Four Humours had much less support. Rational Explanations diagnosis using urine analysis. Miasma and ‘Spontaneous Generation’ blamed for i)The Theory of the Four Humours - an New Scientific Approach disease by most doctors. imbalance in either blood, phlegm, black i) English doctor - Thomas Sydenham - Major Turning Point Alert!!!! bile, yellow bile causes illness encourages a return to diagnosis based on i)In 1861 Louis Pasteur of France proved the the 2) Miasma - (Bad smells) observation - not all illnesses are the same - microbes (germs) were the cause not the result of An invisible poisonous gas emerges rest and good food better than decay and disease - killing off 4 Humours, the wherever there is foul smelling waste and bleeding/purging Miasma theory and the theory Spontaneous this gas causes illness, especially ii) King Charles II sets up the Royal Society in Generation. contagious illness like the plague. London to encourage doctors to look for a ii)Surgeon Joseph Lister used Pasteur’s knowledge more scientific cause of illness and to try The continuing influence of Galen and to greatly reduced the rate of post-surgical experimenting with new techniques infection by using carbolic bandages and sprays to Hippocrates: iii) The invention of the printing press in the keep the surgery sterile. -

Sawbones 275: the First Pharmacist Published on May 18Th, 2019 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family

Sawbones 275: The First Pharmacist Published on May 18th, 2019 Listen here on themcelroy.family Clint: Sawbones is a show about medical history, and nothing the hosts say should be taken as medical advice or opinion. It's for fun. Can't you just have fun for an hour, and not try to diagnose your mystery boil? We think you've earned it. Just sit back, relax, and enjoy a moment of distraction from that weird growth. You're worth it. [theme music plays] [applause] Justin: Hello, everybody, and welcome to Sawbones, a marital tour of misguided medicine. I'm your cohost, Justin McElroy. [audience cheers] Sydnee: And I'm Sydnee McElroy. [audience cheers] Justin: Yes. Yes. We all know. We have something more important to discuss. My brother, not three minutes ago... Sydnee: [laughs] Justin: Let me take you back. Sydnee: We were right there. We saw the whole thing from right there. Justin: Wait. We saw the whole thing. Let me back up. Today, my family went to The Ruby Slipper Cafe. [audience cheers] Justin: I did not. I went and took my daughter, my baby, back for a nap. Because I'm a hero. I ate a lamp-heated sandwich that I bought at a store. That's not important. I come downstairs and I ask— we're going to the aquarium. I don't want to. But we have to, because we go to the aquarium every time. Because we have— Sydnee: We go anywhere. Not 'cause it's not great. He was just [whispers] kind of tired. -

A Study of Nursing Practices Used in the Management of Infection in Hospitals, 1929- 1948

A Study of Nursing Practices Used in the Management of Infection in Hospitals, 1929- 1948 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences 2014 David Justham School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work 2 LIST OF CONTENTS Page List of Contents 2 Abstract 6 Declaration 7 Copyright Statement 8 List of Abbreviations 9 Acknowledgements 10 Preface 11 Chapter 1 Introduction and Method 12 1.1 The Context of the Study 12 1.2 Rationale for the Study 14 1.3 Research Question 20 1.4 Methods Used and Methodological Considerations 21 1.4.1 Oral History Method 22 1.4.2 Oral History and Memory 25 1.4.3 Sampling Strategy 30 1.4.4 Ethical Considerations 32 1.4.5 Recording Oral History 33 1.4.6 Transcribing Data 34 1.4.7 Analysis of Oral History Data 38 1.4.8 Archival Research 39 1.4.9 Use of Memoirs 41 1.5 Historiographical Considerations 41 1.5.1 Nursing History as a Separate Field of History 41 1.5.2 The Interpretation of Data to Inform History 43 1.6 Summary of Method 47 1.7 Structure of the Thesis 47 Chapter 2 Underpinning Concepts of Relevance to Infection in the 50 1930s and 1940s 2.1 Introduction 50 3 2.2 Miasma and Germ Theory 50 2.3 Ideas of Sanitation 54 2.4 Removing Dirt 58 2.5 Fear of Infection 61 2.6 Immunology 64 2.7 The Impact of Sulphonamides and Antibiotics 67 2.8 Development of Infection Control 72 2.9 Summary 75 Chapter 3 Issues in the History of Nursing 77 3.1 Introduction 77 3.2 The Hiddenness of Nursing Work 77 3.3 Status Issues in Nursing 82 3.4 -

Public Health and Sanitation in Colonial Lahore, 1849-1910 by Maysoon Sheikh a Thesis Presented to the University of Waterloo In

Public Health and Sanitation in Colonial Lahore, 1849-1910 by Maysoon Sheikh A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Maysoon Sheikh 2018 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Rachel Berger Associate Professor, History Concordia University Supervisor Douglas Peers Professor, History and Dean of Arts University of Waterloo Internal Member Dan Gorman Professor, History University of Waterloo Internal Member Jesse Palsetia Associate Professor, History University of Guelph Internal-external Member Heather Smyth Associate Professor, English Language and Literature University of Waterloo ii Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract The British annexation of the Punjab in 1849 had important consequences for the city of Lahore. Indeed, the British occupation prompted Lahore’s transformation into a “modern” colonial city. New designs for urbanization, environmental reform, and sanitary improvement were implemented by the city’s new administrators, resulting in important changes in Lahore’s physical and social environment. At first, the impulse to redevelop the city stemmed largely from colonial anxieties about threats to the health of the army and Lahore’s British residents; however, by the late nineteenth century, this “enclavist” approach was replaced by a more extensive public health scheme that was geared towards managing and safeguarding the city’s entire population. -

Communicable Diseases and Germ Theory in Colonial India – an Assessment*

Indian Journal of History of Science, 48.3 (2013) 513-530 COMMUNICABLE DISEASES AND GERM THEORY IN COLONIAL INDIA – AN ASSESSMENT* Srabani Sen** The transition from miasma to germ theory in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century has been widely documented in narratives about the discovery of microbes, the evidence of contamination, or the procedures for sterilizations. This was a radical change in the history of understanding disease, treating and preventing it, and that shift marked a new era in medicine. However, it is important to find out how did that shift happen, what was it actually like to live through the transition while dealing with the disease, contagion, infection, transmission, treatment or prevention? This project was aimed to investigate the establishment of germ theory as the central paradigm in tropical medicine and the impact of germ theory on the indigenous physicians in colonial India. The study consists of the five following chapters: I. The Indo-Portuguese exchange of medical knowledge in colonial Goa. II. Bacteriological Investigations by Europeans in British India. III. The Debates on the Contagion as the origin of diseases. IV. The Impact of Germ Theory of Disease on Indigenous Practitioners. V. Bacteriology in the Service of Communicable diseases in Colonial India. First chapter presents the Indo-Portuguese exchange of medical knowledge in colonial Goa. By 1510 the Portuguese established themselves on the west coast of India with their capital at Goa and became regular visitors to India as traders, soldiers, sailors, adventurers, missionaries, naturalists, physicians and surgeons. Though, all the trading companies sent out physicians and surgeons with their expeditions, they had little experience of tropical diseases.