STUDENT OVERVIEW London 1854: Cesspits, Cholera and Conflict Over

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F:\RSS\Me\Society's Mathemarica

School of Social Sciences Economics Division University of Southampton Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK Discussion Papers in Economics and Econometrics Mathematics in the Statistical Society 1883-1933 John Aldrich No. 0919 This paper is available on our website http://www.southampton.ac.uk/socsci/economics/research/papers ISSN 0966-4246 Mathematics in the Statistical Society 1883-1933* John Aldrich Economics Division School of Social Sciences University of Southampton Southampton SO17 1BJ UK e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper considers the place of mathematical methods based on probability in the work of the London (later Royal) Statistical Society in the half-century 1883-1933. The end-points are chosen because mathematical work started to appear regularly in 1883 and 1933 saw the formation of the Industrial and Agricultural Research Section– to promote these particular applications was to encourage mathematical methods. In the period three movements are distinguished, associated with major figures in the history of mathematical statistics–F. Y. Edgeworth, Karl Pearson and R. A. Fisher. The first two movements were based on the conviction that the use of mathematical methods could transform the way the Society did its traditional work in economic/social statistics while the third movement was associated with an enlargement in the scope of statistics. The study tries to synthesise research based on the Society’s archives with research on the wider history of statistics. Key names : Arthur Bowley, F. Y. Edgeworth, R. A. Fisher, Egon Pearson, Karl Pearson, Ernest Snow, John Wishart, G. Udny Yule. Keywords : History of Statistics, Royal Statistical Society, mathematical methods. -

History of the Development of the ICD

History of the development of the ICD 1. Early history Sir George Knibbs, the eminent Australian statistician, credited François Bossier de Lacroix (1706-1777), better known as Sauvages, with the first attempt to classify diseases systematically (10). Sauvages' comprehensive treatise was published under the title Nosologia methodica. A contemporary of Sauvages was the great methodologist Linnaeus (1707-1778), one of whose treatises was entitled Genera morborum. At the beginning of the 19th century, the classification of disease in most general use was one by William Cullen (1710-1790), of Edinburgh, which was published in 1785 under the title Synopsis nosologiae methodicae. For all practical purposes, however, the statistical study of disease began a century earlier with the work of John Graunt on the London Bills of Mortality. The kind of classification envisaged by this pioneer is exemplified by his attempt to estimate the proportion of liveborn children who died before reaching the age of six years, no records of age at death being available. He took all deaths classed as thrush, convulsions, rickets, teeth and worms, abortives, chrysomes, infants, livergrown, and overlaid and added to them half the deaths classed as smallpox, swinepox, measles, and worms without convulsions. Despite the crudity of this classification his estimate of a 36 % mortality before the age of six years appears from later evidence to have been a good one. While three centuries have contributed something to the scientific accuracy of disease classification, there are many who doubt the usefulness of attempts to compile statistics of disease, or even causes of death, because of the difficulties of classification. -

Prime Soho Restaurant Opportunity

Prime Soho Restaurant Opportunity 49 LEXINGTON STREET Location Lexington Street is a charming street in the very heart of Soho and surrounded by Soho’s edgy bars, cafés and shops and connects Broadwick Street and Beak Street, both popular dining and shopping destinations. The property is situated on the northern end of Lexington Street close to its junction within an elegant Grade 2 listed Georgian building. It is a hotspot for eating, drinking and shopping, and is busy seven days a week attracting shoppers, tourists, office workers and residents. Other nearby operators include; Bao, Andrew Edmunds, Mildreds, Fernandez and Wells, Temper, The Ivy Soho Brasserie, Said, Tapas Brindisa, Yauatcha, Ember Yard, Polpetto, The Duck and Rice and Social Eating House. Nearby is Carnaby, home to over 60 restaurants, pubs, bars and cafés including the 3-floor foodie hub, Kingly Court with over 20 independent and concept restaurants including Whyte & Brown, Señor Ceviche and The Rum Kitchen. The Property The restaurant will be delivered in a shell condition with a new kitchen extract duct installed. Temper Ember Yard Bao The Duck and Rice PRIME SOHO RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITY 49 LEXINGTON STREET Accommodation Service charge and Insurance The restaurant has the following approximate gross floor areas net of The service charge for the current financial year is stairs: estimated at £5,200 per annum. Insurance is estimated at £600 per Ground 460 sq ft annum. Further information available on request. Basement 531 sq ft Garden 271 sq ft Rates Total 1,262 sq ft Interested parties should make their own enquiries with the Local Authority. -

Hamilton's Forgotten Epidemics

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics / D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-9782417-4-2 Print catalogue data is available from Library and Archives Canada, at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca Cover Image: Historical City of Hamilton. Published by Rice & Duncan in 1859, drawn by G. Rice. http://map.hamilton.ca/old hamilton.jpg Cover Design: Robert Huang Group Photo: Temara Brown Ch2olera Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Contents FIGURES AND TABLES vii Introduction Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles 2 2 “From Time Immemorial”: British Imperialism and Cholera in India Diedre Beintema 8 3 Miasma Theory and Medical Paradigms: Shift Happens? Ayla Mykytey 18 4 ‘A Rose by Any Other Name’: Types of Cholera in the 19th Century Thomas Siek 24 5 Doesn’t Anyone Care About the Children? Katlyn Ferrusi 32 6 Changing Waves: The Epidemics of 1832 and 1854 Brianna K. Johns 42 7 Charcoal, Lard, and Maple Sugar: Treating Cholera in the 19th Century S. Lawrence-Nametka 52 iii 8 How Disease Instills Fear into a Population Jacqueline Le 62 9 The Blame Game Andrew Turner 72 10 Virulence Victims in Victorian Hamilton Jodi E. Smillie 80 11 On the Edge of Death: Cholera’s Impact on Surrounding Towns and Hamlets Mackenzie Armstrong 90 12 Avoid Cholera: Practice Cleanliness and Temperance Karolina Grzeszczuk 100 13 New Rules to Battle the Cholera Outbreak Alexandra Saly 108 14 Sanitation in Early Hamilton Nathan G. -

Rare Long-Let Freehold Investment Opportunity INVESTMENT SUMMARY

26 DEAN STREET LONDON W1 Rare Long-Let Freehold Investment Opportunity INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Freehold. • Prominently positioned restaurant and ancillary building fronting Dean Street, one of Soho’s premier addresses. • Soho is renowned for being London’s most vibrant and dynamic sub-market in the West End due to its unrivalled amenity provisions and evolutionary nature. • Restaurant and ancillary accommodation totalling 2,325 sq ft (216.1 sq m) arranged over basement, ground and three uppers floors. • Single let to Leoni’s Quo Vadis Limited until 25 December 2034 (14.1 years to expiry). • Home to Quo Vadis, a historic Soho private members club and restaurant, founded almost a 100 years ago. • Restaurant t/a Barrafina’s flagship London restaurant, which has retained its Michelin star since awarded in 2013. • Total passing rent £77,100 per annum, which reflects an average rent of £33.16 per sq ft. • Next open market rent review December 2020. • No VAT applicable. Offers are invited in excess of £2,325,000 (Two Million Three Hundred and Twenty-Five Thousand Pounds), subject to contract. Pricing at this level reflects a net initial yield of 3.12% (after allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.35%) and a capital value of £1,000 per sq ft. Canary Wharf The Shard The City London Eye South Bank Covent Garden Charing Cross Holborn Trafalgar Square Leicester Square Tottenham Court Road 26 DEAN Leicester Square STREET Soho Square Gardens Tottenham Court Road Western Ticket Hall Oxford Street London West End LOCATION & SITUATION Soho has long cemented its reputation as the excellent. -

Biodefense and Constitutional Constraints

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2011 Biodefense and Constitutional Constraints Laura K. Donohue Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 11-96 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/677 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1882506 4 Nat'l Security & Armed Conflict L. Rev. 82-206 (2014) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons BIODEFENSE AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS Laura K. Donohue* I. INTRODUCTION"""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""" & II. STATE POLICE POWERS AND THE FEDERALIZATION OF U.S. QUARANTINE LAW """"""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""" 2 A. Early Colonial Quarantine Provisions""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""" 3 """"""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""" 4 """""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""&) -

16/18 Beak Street Soho, London W1F 9RD Prime Soho Freehold

16/18 Beak Street Soho, London W1F 9RD Prime Soho Freehold INVESTMENT SUMMARY n Attractive, six storey period building occupying a highly prominent corner site. n Situated in a prime Soho position just off Regent Street, in direct proximity of Golden Square and Carnaby Street. n Double fronted restaurant with self contained, high specification, triple aspect offices above. n Total accommodation of 1,097.84 sq m (11,817 sq ft) with regular floorplates of approximately 1,700 sq ft over the upper floors. n Multi let to five tenants with 46% of the income secured against the undoubted covenant of Pizza Express on a new unbroken 15 year lease. n Total rent passing of £645,599 per annum. n Newly let restaurant, and reversionary offices, let off a low average base rent of less than £50 per sq ft. n Substantial freehold interest. n Multiple asset management opportunities to enhance value. n Seeking offers in excess of £12.85 million reflecting the following attractive yield profile and a capital value of £1,087 per sq ft: n Net Initial Yield: 4.75% n Equivalent Yield: 5.15% n Reversionary Yield: 5.30% T W STREE RET IM R RGA E MA P G OLE CAVENDISH E SQUARE N T S S TR T R TOTTENHAM E E E E E COURT ROAD T AC L T A P ST TT . G FORD STREET IL HENRIE OX E S HI GH ST. SOHO SQUARE P O OXFORD B LA E CIRCUS RW N EET R D C I FORD ST CK H OX S A T WA T RE STRE G R EE R I R R N . -

8-12 Broadwick Street

8-12 BROADWICK STREET 898 sq ft of contemporary loft-style office space on the 4th floor UNIQUE space 8-12 Broadwick Street is a unique office building in the heart of Soho. The available loft-style space is on the 4th floor and has been refurbished in a contemporary style. The office features a large central skylight, views over Soho and original timber flooring. The floor benefits from a demised WC and shower as well as a fitted kitchenette. SPECIFICATION • Loft-style offices with fantastic natural light • Original parquet timber flooring • Demised WC and shower • Perimeter trunking • New comfort cooling system • Refurbished entrance and common parts • Fitted kitchenette • Lift to 3rd floor • BT internet available 4th FLOOR PLAN 898 sq ft / 84 sq m Shower NORTH Kitchen CLICK HERE FOR VIRTUAL tour 360 BROADWICK STREET LOCATION Broadwick Street sits in an area of Soho famed for its record shops, markets and restaurant scene, with the iconic Carnaby Street an easy walking distance away. There are excellent transport links available, with Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Circus, Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus within a 10-minute walk. Oxford Street Oxford Berwick Street Tottenham Court Road Circus BREWDOG Dean Street SOULCYCLE Noel Street Street Wardour Poland Street Poland Tenants will benefit from discounts from tens of Soho food, drink and fashion staples with the Soho NEIGHBOURHOOD London Soho Square TED’S Gin Club CARD. Neighbourhood Card holders are BLANCHETTE GROOMING CARNABY entitled to receive 10% off full price STREET D’Arblay Street merchandise, menus or services at Sheraton Street participating stores, restaurants, bars and cafés across Soho and Carnaby. -

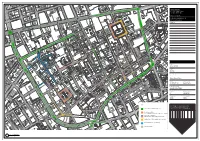

Soho OS Map SKETCH-BEN

RATHBONE BERNERS PLACE STREET REGENT STREET MARGARET STREET OXFORD GREAT NEW STREET BERNERS TITCHFIELD PLACE STREET WELLS EASTCASTLE STREET STREET STREET BUCKNALL Margaret Perry's ST GILES' CIRCUS GREAT Court Transit Studio Place PORTLAND STREET 43 Frith Street, Soho, OXFORD Adam ROAD STREET MARKET and STREET ROMAN PLACE EARNSHAW Eve BUCKNALL London, W1D 4SA Court STREET WINSLEY FALCONBERG MARKET 020 3877 0006 STREET SOHO PLACE MEWS Central STREET STREET CASTLE St Giles [email protected] GREAT Piazza transitstudio.co.uk PLACE Post MARKET ST GILES STREET HIGH HIGH GILES STREET GREAT STREET ST Market Revisions CASTLE GREAT PLACE Hospital Wall Court CHAPEL ROW DENMARK STREET SUTTON OXFORD SQUARE STREET SOHO ROAD ROMAN WARDOUR STREET HOLLEN STREET STREET DENMARK 5 STREET St Giles YARD Hospital GOSLETT (site of) COMPTON NEW OXFORD CIRCUS HILLS PLACE STREET ORANGE NOEL STREET Argyll Swallow Passage PLACE SQUARE RAMILLIES CARLISLE Post YARD Street STREET SOHO RAMILLIES Play Area SHERATON STREET St BERWICK DEAN STREET Flitcroft MANETTE STREET STREET SWALLOW Bateman's Ps REGENT ST CHARING GILES PLACE Buildings PASSAGE STREET CROSS STACEY STREET D'ARBLAY WARDOUR STREET Posts ROAD POLAND STREET MEWS STREET STREET CHAPONE STREET SM ARGYLL PLACE COMPTON PHOENIX ARGYLL LITTLE NEW Court Anne's STREET St Posts GREEK STREET STREET PORTLAND MEWS ROYALTY MARLBOROUGH BUILDINGS MEWS GREAT RICHMOND FRITH Car Park WARDOUR STREET St Giles House STREET STREET Ct STREET Flaxman BATEMAN Walk St LIVONIA Caxton STREET AVENUE Greek Marlborough Posts BROADWICK -

Vol 37 Issue 1.Qxp

EH Forrest 27 Mathurin P, Abdelnour M, Ramond M-J et al. Early change in critical appraisal and meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med bilirubin levels is an important prognostic factor in severe 1995; 23:1430-–9. alcoholic hepatitis treated with prednisolone. Hepatol 2003; 32 Bollaert P-E, Charpentier C, Levy B, Debouvrie M, Audiebert G, 38:1363–9 Larcan, A. Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic 28 Morris JM, Forrest EH. Bilirubin response to corticosteroids in doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med 1998; 26:645–50. alcoholic hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 17:759–62. 33 Staubach K-H, Schroeder J, Stuber F,Gehrke K,Traumann E, Zabel 29 Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. P. Effect of pentoxifylline in severe sepsis: results of a randomised Pentoxifylline improves short term survival in severe alcoholic double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Surg 1998; hepatitis: a double blind placebo controlled trial. Gastroenterol 133:94–100. 2000; 119:1637–48. 34 Bacher A, Mayer N, Klimscha W, Oismuller C, Steltzer H, 30 Lefering R, Neugebauer EAM. Steroid controversy in sepsis and Hammerle A. Effects of pentoxifylline on haemodynamics and septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 1995; 23:1294–303. oxygenation in septic and non-septic patients. Crit Care Med 31 Cronin L, Cook DJ, Carlet J et al. Corticosteroid for sepsis: a 1997; 25:795–800. GENERAL MEDICINE BOOKS YOU SHOULD READ of the spread of cholera across Europe and its eventual spread into The Medical Detective by Sandra England in the early nineteenth Hempel. -

Now on Cholerad--The Special Lecture in the Second British ,Epidemiology

~~,,~lnalof Epidemiology Vol. 8. No. 4 Oct --- $now on cholerad--The Special Lecture in the second British ,Epidemiology and ...Public Health Course at Kansai .Systems Laboratory dn 24 AIJ~S~I968 - .- -- .-- -- - " -- Shinichi Tan'ihara ', Seiji Morioka 2, Kazunori Kodama 3, Tsutomu Hashimoto 2, Hiroshi Yanagawa I, and Walter W Holland TheSecond British Epidemiology and Public Health Course was held from 19 to 25 August 1996 in Osaka as a satellite meeting for the 14th lnternational Scientific Meeting of the lnternational Epidemiological Association. Thirty-three researchers from 10 countries participated in the course. Professor Walter W Holland gave a special lecture about Snow on cholera during the course, and the lecture revealed that Henry Whitehead who was a junior priest at that time contributed to Snow's work to prevent the cholera outbreak in Golden Square in 1854. What John Snow did in his life are reviewed in detail in this paper J Epiderniol, 1998 ; 8 : 185-1 94. -3 John Snow, cholera, Henry Whitehead, British Course After the success of the First British Epidemiology and as my first lecture to my students. I think almost all the Public Health Course in 1994 I). the \econd course was Japanese professors of epidemiology or publlc health would planned. The organising committee for the course (see Table Like to speak about John Snow in their lectures. I regret that in 1) was able to prepare it from 19 August to 25 August 1996 in the first course, I missed his lecture. But today, I can listeihto Osaka, just bel'ore the 14th International Scientific Meeting for the lecw from fust to last. -

The Ghost Map: the Story of London’S Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World by Steven Johnson

Welcome to our April book, Historians! We will meet on Tuesday, April 3 at 6:30 to discuss The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World by Steven Johnson. This is the story of the cholera outbreak in Victorian London in 1854. The book centers on Dr. John Snow who created a map of the cholera cases and the Reverend Henry Whitehead who knew the community through his church work and who was able to use this “social intelligence” to figure out the source of the outbreak, the now infamous water pump on Broad Street. In The Ghost Map, we meet these men and the victims and medical workers, both named and unnamed, who worked to stop a disease that no one understood or understood how it spread. Fighting disease in a densely populated urban environment was a new development in medicine. With two and one-half million inhabitants, no city in history had been as large as London is in 1854. When a disease like cholera hits, the results are devastating. As Johnson explains, cholera acts swiftly upon the body. People can die in as fast as twelve hours as cholera causes you to lose the water in your body. Sadly, because the water keeping your brain hydrated is the last water to disappear, victims are consciously dying, fully aware of their circumstances. The medical community believes that cholera is spread by bad air, what is called the miasma theory. Snow and Whitehead provide the evidence that cholera is spread by bad water, but the medical community is slow to accept the evidence, even when shutting down the Broad Street water pump ends the epidemic.