Thomas Moore Memoirs of Captain Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

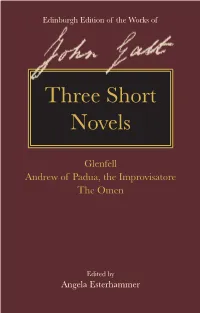

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Fiction Relating to Ireland, 1800-29

CARDIFF CORVEY: READING THE ROMANTIC TEXT Archived Articles Issue 4, No 2 —————————— SOME PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–1829 —————————— Jacqueline Belanger JACQUELINE BELANGER FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–29 I IN 1829, just after Catholic Emancipation had been granted, Lady Morgan wrote: ‘Among the Multitudinous effects of Catholic emancipation, I do not hesitate to predict a change in the character of Irish authorship’.1 Morgan was quite right to predict a change in ‘Irish authorship’ after the eventful date of 1829, not least because, in the first and most obvious instance, one of the foremost subjects to have occupied the attentions of Irish authors in the first three decades of the early nineteenth century— Catholic Emancipation—was no longer such a central issue and attention was to shift instead to issues revolving around parliamentary independence from Britain. However, while important changes did occur after 1829, it could also be argued that the nature of ‘Irish authorship’—and in particular authorship of fiction relating to Ireland—was altering rapidly throughout the 1820s. It was not only the case that the number of novels representing Ireland in some form increased over the course of the 1820s, but it also appears that publishing of this type of fiction came to be dominated by male authors, a trend that might be seen to relate both to general shifts in the pattern for fiction of this time and to specific conditions in British expectations of fiction that sought to represent Ireland. It is in order to assess and explore some of the trends in the production and reception of fiction relating to Ireland during the period 1800–29 that this essay provides a bibliography of those novels with significant Irish aspects. -

Evolving Representations of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Genre Fiction

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE IMAGINING IRISHNESS: EVOLVING REPRESENTATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENRE FICTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By R. MICHELLE LEE Norman, Oklahoma 2012 IMAGINING IRISHNESS: EVOLVING REPRESENTATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENRE FICTION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT BY ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Cottom, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Francesca Sawaya ______________________________ Dr. Timothy Murphy ______________________________ Dr. Daniela Garofalo ______________________________ Dr. Judith Lewis © Copyright by R. MICHELLE LEE 2012 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking Daniel Cottom for directing this dissertation and seeing me through nine years of graduate work. I knew I could always depend on his good advice and practical perspective, no matter the issue. His encouragement, guidance, patience, and sense of humor helped get me to this point, and I am a stronger writer and a better scholar because of him. I am also grateful to my committee members, Francesca Sawaya, Timothy Murphy, Daniela Garofalo, and Judith Lewis. Their kind words, valuable criticism—and, sometimes, their willingness to chat over a much-needed martini—have meant so much to me. This project would not be the same without the indispensable assistance of the many librarians and archivists in Ireland and America who helped me locate research materials. Their extensive knowledge and resourcefulness made sifting through countless of boxes, letters, and manuscripts a smooth and pleasant experience. I would like to thank Mr. Robin Adams and the other librarians in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library at Trinity College Dublin for helping me with my research on Bram Stoker, and Tara Wenger and Elspeth Healey at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library in Lawrence, Kansas for access to the P. -

Republic of Ireland. Wikipedia. Last Modified

Republic of Ireland - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Republic of Ireland Permanent link From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page information Data item This article is about the modern state. For the revolutionary republic of 1919–1922, see Irish Cite this page Republic. For other uses, see Ireland (disambiguation). Print/export Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ or /ˈɑrlənd/; Irish: Éire, Ireland[a] pronounced [ˈeː.ɾʲə] ( listen)), also known as the Republic Create a book Éire of Ireland (Irish: Poblacht na hÉireann), is a sovereign Download as PDF state in Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island Printable version of Ireland. The capital is Dublin, located in the eastern part of the island. The state shares its only land border Languages with Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of Acèh the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Адыгэбзэ Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, Saint Flag Coat of arms George's Channel to the south east, and the Irish Sea to Afrikaans [10] Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" Alemannisch the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The head "The Soldiers' Song" Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript of government, the Taoiseach, is nominated by the lower Ænglisc disabled or does not have any supported house of parliament, Dáil Éireann. player. You can download the clip or download a Aragonés The modern Irish state gained effective independence player to play the clip in your browser. from the United Kingdom—as the Irish Free State—in Armãneashce 1922 following the Irish War of Independence, which Arpetan resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. -

Ancient Greek Tragedy and Irish Epic in Modern Irish

MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katherine Anne Hennessey, B.A., M.A. ____________________________ Dr. Susan Cannon Harris, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana March 2008 MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE Abstract by Katherine Anne Hennessey Over the course of the 20th century, Irish playwrights penned scores of adaptations of Greek tragedy and Irish epic, and this theatrical phenomenon continues to flourish in the 21st century. My dissertation examines the performance history of such adaptations at Dublin’s two flagship theatres: the Abbey, founded in 1904 by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, and the Gate, established in 1928 by Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards. I argue that the potent rivalry between these two theatres is most acutely manifest in their production of these plays, and that in fact these adaptations of ancient literature constitute a “disputed territory” upon which each theatre stakes a claim of artistic and aesthetic preeminence. Partially because of its long-standing claim to the title of Ireland’s “National Theatre,” the Abbey has been the subject of the preponderance of scholarly criticism about the history of Irish theatre, while the Gate has received comparatively scarce academic attention. I contend, however, that the history of the Abbey--and of modern Irish theatre as a whole--cannot be properly understood except in relation to the strikingly different aesthetics practiced at the Gate. -

The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1988 The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798 Judith A. Ridner College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ridner, Judith A., "The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798" (1988). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625476. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-d1my-pa56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIETY OF UNITED IRISHMEN AND THE REBELLION OF 1798 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Judith Anne Ridner 1988 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts *x CXm j UL Author Approved, May 1988 Thomas Sheppard Peter Clark James/McCord TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS................................................. iv ABSTRACT................................. V CHAPTER I. THE SETTING.............. .................................. 2 CHAPTER II. WE WILL NOT BUY NOR BORROW OUR LIBERTY.................... 19 CHAPTER III. CITIZEN SOLDIERS, TO ARMS! ........................... 48 CHAPTER IV. AFTERMATH................................................. 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY........................................................... 87 iii ABSTRACT The Society of United Irishmen was one of many radical political clubs founded across the British Isles in the wake of the American and French Revolutions. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 11:58:33PM Via Free Access Gothic Genres

2 Gothic genres: romances, novels, and the classifications of Irish Romantic fiction • n his Revelations of the dead-alive (1824), John Banim depicts his time- Itravelling narrator encountering future interpretations of the fiction of Walter Scott. In twenty-first-century London, Banim’s narrator realises, Scott is little read; when he is, he is understood, as James Kelly points out, ‘not as the progenitor of the historical novel but rather as the last in line of an earlier Gothic style’.1 According to the readers encountered in his travels, Scott is actually the ‘last and most successful adaptor or modifier’ of a gothic literary mode introduced by Walpole and practised by Lewis and Radcliffe.2 Commenting slyly on the question of Scott’s originality while also denying lasting fame to the period’s most financially and popularly successful novelist, Banim’s Revelations of the dead-alive perceptively reveals the formal and generic slippages of historical and gothic fiction in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As it does so, it underscores the formal and generic fluidity of Romantic-era literature. While modern-day readers frequently view gothic and historical fictions of this period as distinctly different types of writing, especially in the period following the publication of Waverley (1814), contemporary accounts of these fictions are much more equivocal in their categorisations of works that were unquestioningly understood as cross-formal and cross-generic. Looking back to the novels of James White, considered in Chapter 1, we see the manner in which late eighteenth-century critics struggled with the formal classifications that are often accepted without question today. -

BIOGRAPHY 43 Fitzgerald, Brian. the Anglo-Irish

BIOGRAPHY 43 FitzGerald, Brian. The Anglo-Irish; three representative types: Cork, Ormonde, Swift, 1602-1745. London, New York: 1952. 369 p. Bibliography: p. 361-363. The author uses three famous figures to illustrate the three phases of the Anglo-Irish rise to power; together they compose the "man of the Ascendancy." The men are Richard Boyle, 1st earl of Cork, and a capitalist settler; James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde, an aristocratic landlord; and Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral and protestant patriot. An interesting presentation of 150 years of Irish history. 44 O'Donoghue, David James. The poets of Ireland; a biographical dictionary with bibliographical particulars. London: 1892-93. 265, x p. A biographical dictionary of Irish poets, including some who were known more for prose than poetry. Only scanty biographical facts are given in many places, but the compiler does list bibliographies of the poet's works. The interest of this work lies in the fact that, at its publication, there vas no book of similar nature in existence; it was meant really as a beginning for a dictionary of Irish writers. 45 Ryan, Richard. Biographia hibernica A biographical dictionary of the worthies of Ireland. London: 1819-21. 2 v. Ryan finds little to criticize about his subjects. His purpose is to "reveal them... in their early grandeur" or "at least to lead us to the spots hallowed by their presence, to shew us the memorials of their hands, and point out the sublime track by which they ascended to immortality." Outdated, but has some interesting facts. -

William Henry Curran, > Barrister at Law

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com THE LIFE of THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JOHN PHILPOT CURRAN, LATE MASTER OF THE ROLLS IN IRELAND. BY HIS SON, WILLIAM HENRY CURRAN, > BARRISTER AT LAW. IN TWO VOLUMES. WOL. II. LONDON : PRINTED FOR ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND CO. EDINBURGH, Long MAN, HuRst, RREs, on ME, and Brown, AND HURST, RoRINson, AND Co. LoNDoN. - - 1819. THE LIFE of THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JOHN PHILPOT CURRAN, LATE MASTER OF THE ROLLS IN IRELAND. BY HIS SON, WILLIAM HENRY CURRAN, _` BARRISTER AT LAW. IN TWO VOLUMES, WOL. II. LONDON : PRINTED FOR ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND CO. EDINBURGH, LoNGMAN, HURST, REEs, or ME, AND Brown, AND HURsr, RoRINson, AND Co. LoNDON. - 1819. C O N T E N T S TO - WOL. II. == CHAPTER I. * - Reb lli º of 1798—Its causes—Unpopular system of i.”-Influence of the French Revolution— ased *lligence in Ireland–Reform societies— j jºini, views and proceedings–Ap "one-N * France—Anecdote of Theobald Wolfe of the e *mbers of the United Irishmen—Condition *res of th *y and conduct of the aristocracy—Mea "rection * severnment—Public alarm—General in page 1 ºil fH CHAPTER II. 0 en - ry *nd John Sheares - . 45 ºil, CHAPTER III. f M = 'ei ºrn, Jean, Byrne, and Oliver Bond—Reynolds | T*-ord Edward Fitzgerald—his attainder | THE LIFE of THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JOHN PHILPOT CURRAN, LATE MASTER OF THE ROLLS IN IRELAND. -

Fiction of the Irish in England

The Fiction of the Irish in England The Fiction of the Irish in England Tony Murray The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Fiction Edited by Liam Harte Print Publication Date: Oct 2020 Subject: Literature, Literary Studies - 19th Century, Literary Studies - Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers, World Literature Online Publication Date: Oct 2020 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198754893.013.43 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines the way in which Irish fiction has engaged with one of the most persistent features of Irish history over the last 200 years, the migration of its people to England. In doing so, it highlights how novels and short stories have played a role in me diating the experiences of Irish migrants in England and how writers have used fiction to fashion a means by which to articulate a sense of Irish cultural identity abroad. The analysis demonstrates how, over two centuries of fiction about the Irish in England, there has been a discernible shift of emphasis away from matters of primarily public concern to those of a more private dimension, resulting in works that illuminate latent as well as manifest features of the diasporic experience and its attendant cultural allegiances and identities. Keywords: Ireland, fiction, the Irish in England, Anglo-Irish, Irish women in England, second-generation identity IF emigration is ‘a mirror in which the Irish nation can always see its true face’,1 such a mirror is by no means flawless. It has cracks, abrasions, and missing pieces which distort our understanding of how one of the most persistent features of Irish history has affected its people’s perception of themselves. -

William Maume: United Irishman and Informer in Two Hemispheres

William Maume: United Irishman and Informer in Two Hemispheres MICHAEL DUREY I adical and revolutionary movements in Ireland in the eighteenth and Rnineteenth centuries are reputed to have been riddled with spies and informers. Their persistent influence helped to distract attention from other causes of failure. Weaknesses within movements, such as internecine strife among leaders, poorly-conceiv~d strategies and exaggerated estimates of popular support, could be hidden behind an interpretation of events which placed responsibility for failure on a contingency that was normally beyond rebel control. In some respects, therefore, it was in the interests of Irish leaders, and sympathetic later commentators, to exaggerate the influence of spies and informers. 1 Such conclusions are possible, however, only because commentators, both contemporary and modern, have failed to make a distinction between spies, being persons 'engaged in covert information-gathering activities', and informers, who are persons who happen to possess relevant information that they are persuaded to divulge. 2 Admittedly, this distinction is not always clear-cut, for some who begin as informers subsequently agree to become spies. Moreover, from the point of view of the authorities, all information, however acquired, tends to be grist to their intelligence mill. Nevertheless, keeping this distinction clear can help to elucidate some of the problems facing revolutionary societies as they sought to keep their activities secret. It is unlikely, for example, that the United Irishmen in the 1790s were at greater risk from spies, as opposed to informers, than either the Jacobins or the Royalists in France in the same period. At no time could Dublin Town-Major Henry Sirr, or security chief Edward Cooke in Dublin Castle, call on the same security apparatus as was available to the police in Paris under the See, for example, W.J.