Evolving Representations of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Genre Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Fenians: the Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876 Timothy Richard Dougherty Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, Timothy Richard, "Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 143. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the constitutive rhetorical strategies of revolutionary Irish nationalists operating transnationally from 1858-1876. Collectively known as the Fenians, they consisted of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the United Kingdom and the Fenian Brotherhood in North America. Conceptually grounded in the main schools of Burkean constitutive rhetoric, it examines public and private letters, speeches, Constitutions, Convention Proceedings, published propaganda, and newspaper arguments of the Fenian counterpublic. It argues two main points. First, the separate national constraints imposed by England and the United States necessitated discursive and non- discursive rhetorical responses in each locale that made -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

The Same Old Story Chief Science Officers

Fall 2 019 THE SAME OLD STORY A Short Story from the Sci-Fi World 8 CHIEF SCIENCE OFFICERS LOG SUBMITTED BY LT. BRAD JACOBS 23 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Welcome, Greetings, Salutations and yI'el! Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of the Ticonderoga newsletter. As difficult as it may seem to be, we are already moving into the final days of 2019. Like so many years that have come and gone, each has its own good and not so good events. This year, even with it's rough patches, has had an overtone that fits well with this issue. Super, and Super Heroes! We all have to admit sometimes, we would love to be able to be able to move that mountain of laundry with our minds, or see whats in the mystery collectibles boxes with X-Ray vision, or maybe just fly and buzz by our old high school bullies house and ding-dong-ditch em! Well, whatever your first activity might have been once you found out that super powers were yours, that moment may not ever happen. What will happen though, is super hero sized actions that have super sized results every day all across the country by “ordinary” crew who don't let their limits stop them. So that being said, even though we are going to have to move the laundry, buy the box without looking, and run like a mad man after ringing the bell, we still look to the skies, watch for that flash of lightning, and aspire to master our minds powers as we create our perfect hero in our books, films and comics. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Thin, white, and saved : fat stigma and the fear of the big black body Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55p6h2xt Author Strings, Sabrina A. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Thin, White, and Saved: Fat Stigma and the Fear of the Big Black Body A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Sabrina A. Strings Committee in charge: Professor Maria Charles, Co-Chair Professor Christena Turner, Co-Chair Professor Camille Forbes Professor Jeffrey Haydu Professor Lisa Park 2012 Copyright Sabrina A. Strings, 2012 All rights reserved The dissertation of Sabrina A. Strings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 i i i DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Alma Green, so that she might have an answer to her question. i v TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE …………………………………..…………………………….…. iii DEDICATION …...…....................................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………....................v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………...…………………………………….…...vi VITA…………………………..…………………….……………………………….…..vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION………………….……....................................viii -

The Favorite Press Release

!1 of !3 Wednesday, May 22, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE AVANTE GARAGE THEATRE COMPANY ANNOUNCES IT’S LOS ANGELES INAUGURAL PRODUCTION The Award-Winning Avante Garage Theatre Company, formerly of Nashville, and then NYC, will present it’s first production in Los Angeles this Summer at The Avery Schreiber Playhouse in the NOHO Arts District. First up for this talented bunch of professionals is the world premiere of a new play - “THE FAVORITE”, by Los Angeles Playwright Joe Correll. Mr. Correll is the Co-Artistic Director of The Avante Garage Theatre Company along with Avante Garage founder Michael Bouson.# “THE FAVORITE” is a dark comedy about the Holmes siblings who have just lost their mother and are cleaning out their parents' garage for the very last time. Shelby and Megan are competitive sisters with polar opposite world views; their adopted African American brother, Dylan is prone to having lively conversations with inanimate objects. They all have unresolved conflicts that get unpacked along with the mountains of boxes, bags and crates. As the family goes through the endless pile of their parents' accumulated treasures and junk, they relive childhood milestones and touchstones, both joyous and traumatic. Things take an unexpected turn when they uncover a painting that was painted by their mother. She has left a note saying that the painting should go to her favorite child, without specifying which one of them that is. Old wounds are exposed and generously doused in salt until the afternoon comes to a climax when Shelby's husband, Ethan makes a shocking discovery in a dusty old trunk.# Los Angeles Singer/Actress LAURA PHILBIN COYLE plays Shelby. -

Tipperary – It’S a Great Place to Live

Welcome to Tipperary – It’s a great place to live. www.tipperary.ie ü Beautiful unspoilt area with the Glen of Aherlow, mountains and rivers nearby. ü Superb Medical Facilities with hospitals and nursing homes locally. ü Major IR£3.5 million Excel Cultural and Entertainment Centre just opened with Cinemas, Theatre, Art gallery and café. ü Quick Access to Dublin via Limerick Junction Station - just 1hour 40 minutes with Cork and Shannon Airport just over 1 Hour. ü Wealth of sporting facilities throughout to cater for everyone. ü Tremendous Educational Facilities available. Third level nearby. ü Proven Community Spirit with positive attitude to do things themselves’. ü A Heritage Town with a great quality of life and a happy place to live. ü A cheaper place to live - better value for money – new homes now on the market for approx €140k. Where is Tipperary Town? Tipperary Town is one of the main towns in County Tipperary. It is situated on the National Primary Route N24, linking Limerick and Waterford road, and on the National Secondary Route serving Cashel and Dublin, in the heart of the ‘Golden Vale’ in the western half of south Tipperary. It is approximately twenty-five miles from both Clonmel and Limerick. Tipperary town lies in the superb scenic surroundings at the heart of the fertile ‘Golden Vale’. Four miles from the town’s the beautiful secluded Glen of Aherlow between the Galtee Mountains and the Slievenamuck Hills with magnificent panoramic views and ideal for hill walking and pony-trekking. Tipperary is a Heritage town designated as such by Bord Failte Located on the main rail rout from Waterford to Limerick, and in close proximity to Limerick Junction, the town is served with an Express Rail Service on the Cork-Dublin line with a connection to Limerick and www.tipperary.ie 1 Waterford. -

The Same Old Story

The Same Old Story The Same Old Story Ivan Goncharov Translated by Stephen Pearl ALMA CLASSICS AlmA ClAssiCs ltd Hogarth House 32-34 Paradise Road Richmond Surrey TW9 1SE United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com The Same Old Story first published in Russian in 1847 This translation first published by Alma Classics Ltd in 2015 Cover design: nathanburtondesign.com Translation and Translator’s Ruminations © Stephen Pearl, 2015 Published with the support of the Institute for Literary Translation, Russia. Notes © Alma Classics, 2015 Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-562-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents The Same Old Story 1 pArt i 3 Chapter 1 5 Chapter 2 31 Chapter 3 76 Chapter 4 101 Chapter 5 118 Chapter 6 151 pArt ii 173 Chapter 1 175 Chapter 2 204 Chapter 3 222 Chapter 4 261 Chapter 5 294 Chapter 6 313 Epilogue 347 Note on the Text 366 Notes 366 Translator’s Ruminations 375 Acknowledgements 387 To Brigitte always there to slap on the mortar at times when the bricks get dislodged – and this bricklayer is at his testiest S . P. The Same Old Story Part I Chapter 1 ne summer in the villAge of grachi, in the household O of Anna Pavlovna Aduyeva, a landowner of modest means, all its members, from the mistress herself down to Barbos, the watchdog, had risen with the dawn. -

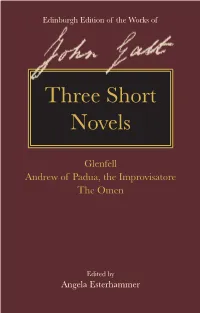

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969

ireiana Edward Norman I Edward Norman A History of Modem Ireland 1800-1969 Advisory Editor J. H. Plumb PENGUIN BOOKS 1971 Contents Preface to the Pelican Edition 7 1. Irish Questions and English Answers 9 2. The Union 29 3. O'Connell and Radicalism 53 4. Radicalism and Reform 76 5. The Genesis of Modern Irish Nationalism 108 6. Experiment and Rebellion 138 7. The Failure of the Tiberal Alliance 170 8. Parnellism 196 9. Consolidation and Dissent 221 10. The Revolution 254 11. The Divided Nation 289 Note on Further Reading 315 Index 323 Pelican Books A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969 Edward Norman is lecturer in modern British constitutional and ecclesiastical history at the University of Cambridge, Dean of Peterhouse, Cambridge, a Church of England clergyman and an assistant chaplain to a hospital. His publications include a book on religion in America and Canada, The Conscience of the State in North America, The Early Development of Irish Society, Anti-Catholicism in 'Victorian England and The Catholic Church and Ireland. Edward Norman also contributes articles on religious topics to the Spectator. Preface to the Pelican Edition This book is intended as an introduction to the political history of Ireland in modern times. It was commissioned - and most of it was actually written - before the present disturbances fell upon the country. It was unfortunate that its publication in 1971 coincided with a moment of extreme controversy, be¬ cause it was intended to provide a cool look at the unhappy divisions of Ireland. Instead of assuming the structure of interpretation imposed by writers soaked in Irish national feeling, or dependent upon them, the book tried to consider Ireland’s political development as a part of the general evolu¬ tion of British politics in the last two hundred years. -

Fiction Relating to Ireland, 1800-29

CARDIFF CORVEY: READING THE ROMANTIC TEXT Archived Articles Issue 4, No 2 —————————— SOME PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–1829 —————————— Jacqueline Belanger JACQUELINE BELANGER FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–29 I IN 1829, just after Catholic Emancipation had been granted, Lady Morgan wrote: ‘Among the Multitudinous effects of Catholic emancipation, I do not hesitate to predict a change in the character of Irish authorship’.1 Morgan was quite right to predict a change in ‘Irish authorship’ after the eventful date of 1829, not least because, in the first and most obvious instance, one of the foremost subjects to have occupied the attentions of Irish authors in the first three decades of the early nineteenth century— Catholic Emancipation—was no longer such a central issue and attention was to shift instead to issues revolving around parliamentary independence from Britain. However, while important changes did occur after 1829, it could also be argued that the nature of ‘Irish authorship’—and in particular authorship of fiction relating to Ireland—was altering rapidly throughout the 1820s. It was not only the case that the number of novels representing Ireland in some form increased over the course of the 1820s, but it also appears that publishing of this type of fiction came to be dominated by male authors, a trend that might be seen to relate both to general shifts in the pattern for fiction of this time and to specific conditions in British expectations of fiction that sought to represent Ireland. It is in order to assess and explore some of the trends in the production and reception of fiction relating to Ireland during the period 1800–29 that this essay provides a bibliography of those novels with significant Irish aspects. -

Ireland Between the Two World Wars 1916-1949, the Irish Political

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Oran Faculty of Letters, Arts and Foreign Languages, Department of Anglo-Saxon Languages Section of English THE IRISH QUESTION FROM HOME RULE TO THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND, 1891-1949 Thesis submitted to the Department of Anglo-Saxon Languages in candidature for the Degree of Doctorate in British Civilization Presented by: Supervised by: Mr. Abdelkrim Moussaoui Prof. Badra Lahouel Board of examiners: President: Dr. Belkacem Belmekki……………………….. (University of Oran) Supervisor: Prof. Badra Lahouel…………………………… (University of Oran) Examiner: Prof. Abbès Bahous………………….. (University of Mostaganem) Examiner: Prof. Smail Benmoussat …………………..(University of Tlemcen) Examiner: Dr. Zoulikha Mostefa…………………………… (University of Oran) Examiner: Dr. Faiza Meberbech……………………… (University of Tlemcen) 2013-2014 1 DEDICATION …To the Memory of My Beloved Tender Mother… 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS By the Name of God the Clement and the Merciful First and foremost, I would like to thank my mentor and supervisor, the distinguished teacher, Professor Badra LAHOUEL, to whom I am so grateful and will be eternally indebted for her guidance, pieces of advice, encouragement and above all, her proverbial patience and comprehension throughout the preparation of this humble research paper. I am also profoundly thankful to whom I consider as a spiritual father, Professor, El Hadj Fawzi Borsali may God preserve him, for his inestimable support and instructive remarks. Special thanks to all my previous teachers through my graduation years: Lakhdar Barka, Moulfi, Maghni, Mostefa, Sebbane, Boutaleb, Layadi, Chami, Rahal, and those we lost Mr Bouamrane and Mr Benali may their souls rest in peace. I would also like to express my gratitude to Mr Moukaddess from England, for his valuable help, and to my friend Abdelkader Kourdouli for being very willing to help.