Fiction of the Irish in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Illusion and Reality in the Fiction of Iris Murdoch: a Study of the Black Prince, the Sea, the Sea and the Good Apprentice

ILLUSION AND REALITY IN THE FICTION OF IRIS MURDOCH: A STUDY OF THE BLACK PRINCE, THE SEA, THE SEA AND THE GOOD APPRENTICE by REBECCA MODEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (Mode B) Department of English School of English, Drama and American and Canadian Studies University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers how Iris Murdoch radically reconceptualises the possibilities of realism through her interrogation of the relationship between life and art. Her awareness of the unreality of realist conventions leads her to seek new forms of expression, resulting in daring experimentation with form and language, exploration of the relationship between author and character, and foregrounding of the artificiality of the text. She exposes the limitations of language, thereby involving herself with issues associated with the postmodern aesthetic. The Black Prince is an artistic manifesto in which Murdoch repeatedly destroys the illusion of the reality of the text in her attempts to make language communicate truth. Whereas The Black Prince sees Murdoch contemplating Hamlet, The Sea, The Sea meditates on The Tempest, as Murdoch returns to Shakespeare in order to examine the relationship between life and art. -

The 'Insider Outsider, in Iris Murdoch,S Bruno's Dream And

にはなぜ目をつぶったのか。ケインズやムーア を正確に認識できないというペシミズムが、ヨー 物それぞれが主役となり、描出される図式に注目 タファーによって「連続性」を象徴した。またク の‘ Sincerity’ をロマンティシズムのあやまちだ ロッパの思想史に長く一貫して継承されてきた重 すると、人間関係の渦巻の連鎖が螺旋、組紐など リモンドをヒンドゥー教のナタラージャ(踊るシ と否定するけれども、彼女が敬意をもって肯定す 要な主題であるのを考えると、彼女の‘ Good’ や 聖書写本『ケルズの書』の抽象文様の世界をス ヴァ神)で象徴しようとしたものは、ヒンドゥー るシモ̶ヌ・ヴェイユの‘ Attention’ とどこがど ‘Perfection’ の理念はその系譜のうちのどこにど トーリーの運びによって描出しようとする、マー 教の重要な特徴である「宗教的寛容の精神」であ う違うと言えるのか。プラトンの洞窟の比喩や、 う位置づけられるものなのか。 ドックの技法が読み取れる。 ろう。ティマーがダンカンとの偶発的な愛の衝動 ピュロンの判断中止の懐疑主義以来、人間は現実 かつてジョイスは『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』 の結果、被った精神的打撃により、「古い神」へ で実験的言語を駆使して『ケルズの書』の宇宙の の信仰の喪失を体験したが、キルケゴールや、サ イメージを表現しようと試みた。ジョイスとはた ン・ファン・デラ・クルスを読み、次第に救われ がいに、きわめて異質の作家であるマードック てゆくプロセスを描いて、マードックは他者認識 研究発表要約 は、渦巻状をなす抽象的な形象の絡まり合いが、 を可能にする「寛容」の精神が小説論の基本にあ 次第に中心を移動させつつ連続してゆく世界の秩 ることを表明している。この作品中に『ケルズの The‘ Insider Outsider’ in Iris Murdoch’s Bruno’s Dream 序をストーリーによって表現することを試みたと 書』の intertextuality は随所に散見できるが、『ケ and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day 考察される。 ルズの書復刻版』の序文で U. エーコが、「未完 マードックは「連続性」の概念を次のように表 の書であるが今後も連続して書き続けることが期 Wendy Jones Nakanishi 現している。ローズはジェラードへの「憧憬と 待される哲学的大作の典型」であると述べたよう 愛」において善意の人であり、連続性の世界の住 に、本作品でもジェラードとクリモンドが「現代 This article compares two novels whose theme is the reflections and regrets of a 人であると述べ、一方ジィーンは、クリモンドと の善と魂」に関する思索の書を、今後も連続して lonely male protagonist. In Bruno’s Dream( 1969), it is Bruno, a sick old man nearing 共に連続性の世界の外側の偶発性をはらんだ実世 書き続けるだろうとの予感を提示して、小説はこ death. In The Remains of the Day( 1990), it is the butler Stevens who, preoccupied with 界に生きているという。 こで閉じている。 his work, has always kept to himself and now discovers a longing to establish human かねてマードックは絵画など芸術作品を援用 本作品は、同性婚や宗教的寛容の精神など、時 contact with others. Both are depicted as essentially alone. In the drama of life they are して作品のメッセージを提示するのだが、本作 代の抱えている問題を先取りしながら、それを超 spectators rather than actors. They are‘ insider outsiders’. 品ではマチスの絵画『ダンス』(Succession)のメ える普遍的な世界観を提示している。 The sense of alienation Bruno and Stevens experience is so acutely described because they are the creation of authors who were‘ insider outsiders’ themselves: inhabiting England but not native to it. -

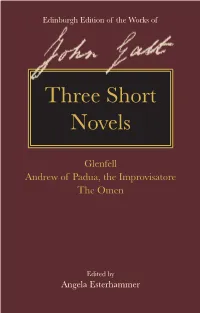

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Fiction Relating to Ireland, 1800-29

CARDIFF CORVEY: READING THE ROMANTIC TEXT Archived Articles Issue 4, No 2 —————————— SOME PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–1829 —————————— Jacqueline Belanger JACQUELINE BELANGER FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–29 I IN 1829, just after Catholic Emancipation had been granted, Lady Morgan wrote: ‘Among the Multitudinous effects of Catholic emancipation, I do not hesitate to predict a change in the character of Irish authorship’.1 Morgan was quite right to predict a change in ‘Irish authorship’ after the eventful date of 1829, not least because, in the first and most obvious instance, one of the foremost subjects to have occupied the attentions of Irish authors in the first three decades of the early nineteenth century— Catholic Emancipation—was no longer such a central issue and attention was to shift instead to issues revolving around parliamentary independence from Britain. However, while important changes did occur after 1829, it could also be argued that the nature of ‘Irish authorship’—and in particular authorship of fiction relating to Ireland—was altering rapidly throughout the 1820s. It was not only the case that the number of novels representing Ireland in some form increased over the course of the 1820s, but it also appears that publishing of this type of fiction came to be dominated by male authors, a trend that might be seen to relate both to general shifts in the pattern for fiction of this time and to specific conditions in British expectations of fiction that sought to represent Ireland. It is in order to assess and explore some of the trends in the production and reception of fiction relating to Ireland during the period 1800–29 that this essay provides a bibliography of those novels with significant Irish aspects. -

The Book of Abstracts

THE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Editor: Ferit Kılıçkaya, Ph.D. Mehmet Akif Ersoy University ____________________________________ Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Department of Foreign Language Education Burdur, TURKEY May 12 – 14, 2016 The 5th International Conference on Language, Literature and Culture [ THE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS ] Editor: Ferit Kılıçkaya, Ph.D. Mehmet Akif Ersoy University ____________________________________ Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Department of Foreign Language Education Burdur, TURKEY May 12 – 14, 2016 i Published by the Department of Foreign Language Education, Faculty of Education, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Burdur, TURKEY Original material in this book of abstracts may be reproduced with the permission of the publisher, provided that (1) the material is not reproduced for sale or profitable gain, (2) the author is informed, and (3) the material is prominently identified as coming from the 5th International Conference in Language, Literature and Culture: The Book of Abstracts. The authors are responsible for the contents of their abstracts and warrant that their abstract is original, has not been previously published, and has not been simultaneously submitted elsewhere. The views expressed in the abstracts in this publication are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by the editor or the reviewers. ©2016 Department of Foreign Language Education, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University ISBN: 9786058327900 ii HONORARY COMMITTEE Hasan Kürklü, Governor of Burdur Ali Orkun Ercengiz, Mayor of Burdur Prof. Dr. Adem -

1 No- G COMEDY and the EARLY NOVELS of IRIS MURDOCH Larry

no- G 1 COMEDY AND THE EARLY NOVELS OF IRIS MURDOCH Larry/Rockefeller A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1968 Approved by Doctoral Committee _Adviser Department of English I a Larry Jean Rockefeller 1969 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PREFACE Why has Iris Murdoch failed in her attempt to resur rect the novel of characters? That is the question which has perplexed so many readers who find in her novels sig nificant statements about the human condition rendered by a talent equalled only by a handful of other writers of our time, and it is the question which the pages follow ing try to answer. In general, the implicit argument under lying those pages is tripartite: (1) only comedy of a kind which resembles closely Murdoch's conception of love will allow a novelist to detach himself enough from his charac ters to give them a tolerant scope within which to humanly exist; (2) Murdoch has succeeded in maintaining that balanced synthesis between acceptance and judgement only in her earli est work and only with complete success in The Bell; and (3) the increasingly bitter tone of her satire — not to mention just the mere fact of her use of satire as a mode for character creation — has, in her most recent work, blighted the vitality of her characters by too strictly limiting them to usually negative meanings. Close analysis has been made, hence, of the ways in which comic devices affect us as readers in our perception of Murdoch's per sons. -

Evolving Representations of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Genre Fiction

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE IMAGINING IRISHNESS: EVOLVING REPRESENTATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENRE FICTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By R. MICHELLE LEE Norman, Oklahoma 2012 IMAGINING IRISHNESS: EVOLVING REPRESENTATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENRE FICTION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT BY ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Cottom, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Francesca Sawaya ______________________________ Dr. Timothy Murphy ______________________________ Dr. Daniela Garofalo ______________________________ Dr. Judith Lewis © Copyright by R. MICHELLE LEE 2012 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking Daniel Cottom for directing this dissertation and seeing me through nine years of graduate work. I knew I could always depend on his good advice and practical perspective, no matter the issue. His encouragement, guidance, patience, and sense of humor helped get me to this point, and I am a stronger writer and a better scholar because of him. I am also grateful to my committee members, Francesca Sawaya, Timothy Murphy, Daniela Garofalo, and Judith Lewis. Their kind words, valuable criticism—and, sometimes, their willingness to chat over a much-needed martini—have meant so much to me. This project would not be the same without the indispensable assistance of the many librarians and archivists in Ireland and America who helped me locate research materials. Their extensive knowledge and resourcefulness made sifting through countless of boxes, letters, and manuscripts a smooth and pleasant experience. I would like to thank Mr. Robin Adams and the other librarians in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library at Trinity College Dublin for helping me with my research on Bram Stoker, and Tara Wenger and Elspeth Healey at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library in Lawrence, Kansas for access to the P. -

Republic of Ireland. Wikipedia. Last Modified

Republic of Ireland - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Republic of Ireland Permanent link From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page information Data item This article is about the modern state. For the revolutionary republic of 1919–1922, see Irish Cite this page Republic. For other uses, see Ireland (disambiguation). Print/export Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ or /ˈɑrlənd/; Irish: Éire, Ireland[a] pronounced [ˈeː.ɾʲə] ( listen)), also known as the Republic Create a book Éire of Ireland (Irish: Poblacht na hÉireann), is a sovereign Download as PDF state in Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island Printable version of Ireland. The capital is Dublin, located in the eastern part of the island. The state shares its only land border Languages with Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of Acèh the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Адыгэбзэ Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, Saint Flag Coat of arms George's Channel to the south east, and the Irish Sea to Afrikaans [10] Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" Alemannisch the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The head "The Soldiers' Song" Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript of government, the Taoiseach, is nominated by the lower Ænglisc disabled or does not have any supported house of parliament, Dáil Éireann. player. You can download the clip or download a Aragonés The modern Irish state gained effective independence player to play the clip in your browser. from the United Kingdom—as the Irish Free State—in Armãneashce 1922 following the Irish War of Independence, which Arpetan resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. -

Of Iris Murdoch

ISSN 1347-4189 No.13 March, 2012 The Mar(k s)of Iris Murdoch Frances White She did not dissent when Philippa said she had an entry in an imaginary diary reading: ‘Mem.: to make my mark.’ Peter Conradi1 Iris Murdoch meant to make her mark on the world. Murdoch scholarship traces the marks she succeeded in leaving as her intellectual legacy. The dynamic of tracing these marks follows two trajectories: inwards and outwards. One spirals inwards to the formative influences on Murdoch’s work through study of the marks left in the myriad letters she wrote and the marginalia annotating her books. The other spirals outwards to plot the imprint Murdoch left through the traces of her presence in the writings of others. The Iris Murdoch Special Collections in the Archives of Kingston University are a rich resource for original research; new acquisitions inspire work by scholars from around the world2. Letters to Raymond Queneau, Hal Lidderdale, John Gheeraert and Harry Weinberger have recently been acquired3, and Anne Rowe and Avril Horner are currently editing Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch 1942 - 19954. Evidence that critical work on Murdoch is burgeoning is demonstrated by recent collections of essays, Iris Murdoch and Moral Imaginations(Roberts and Baumann), Iris Murdoch and Her Work: Critical Essays(Kırca and Okuroglu), and Iris Murdoch and Morality(Rowe and Horner), and by monographs such as Leeson’s Iris Murdoch: Philosophical Novelist and Zuba’s Iris Murdoch’s Contemporary Retrieval of Plato: The Influence of an Ancient Philosopher on a Modern Novelist. But what is even more significant is that Murdoch’s influence appears increasingly ubiquitous. -

Ancient Greek Tragedy and Irish Epic in Modern Irish

MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katherine Anne Hennessey, B.A., M.A. ____________________________ Dr. Susan Cannon Harris, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana March 2008 MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE Abstract by Katherine Anne Hennessey Over the course of the 20th century, Irish playwrights penned scores of adaptations of Greek tragedy and Irish epic, and this theatrical phenomenon continues to flourish in the 21st century. My dissertation examines the performance history of such adaptations at Dublin’s two flagship theatres: the Abbey, founded in 1904 by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, and the Gate, established in 1928 by Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards. I argue that the potent rivalry between these two theatres is most acutely manifest in their production of these plays, and that in fact these adaptations of ancient literature constitute a “disputed territory” upon which each theatre stakes a claim of artistic and aesthetic preeminence. Partially because of its long-standing claim to the title of Ireland’s “National Theatre,” the Abbey has been the subject of the preponderance of scholarly criticism about the history of Irish theatre, while the Gate has received comparatively scarce academic attention. I contend, however, that the history of the Abbey--and of modern Irish theatre as a whole--cannot be properly understood except in relation to the strikingly different aesthetics practiced at the Gate. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 11:58:33PM Via Free Access Gothic Genres

2 Gothic genres: romances, novels, and the classifications of Irish Romantic fiction • n his Revelations of the dead-alive (1824), John Banim depicts his time- Itravelling narrator encountering future interpretations of the fiction of Walter Scott. In twenty-first-century London, Banim’s narrator realises, Scott is little read; when he is, he is understood, as James Kelly points out, ‘not as the progenitor of the historical novel but rather as the last in line of an earlier Gothic style’.1 According to the readers encountered in his travels, Scott is actually the ‘last and most successful adaptor or modifier’ of a gothic literary mode introduced by Walpole and practised by Lewis and Radcliffe.2 Commenting slyly on the question of Scott’s originality while also denying lasting fame to the period’s most financially and popularly successful novelist, Banim’s Revelations of the dead-alive perceptively reveals the formal and generic slippages of historical and gothic fiction in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As it does so, it underscores the formal and generic fluidity of Romantic-era literature. While modern-day readers frequently view gothic and historical fictions of this period as distinctly different types of writing, especially in the period following the publication of Waverley (1814), contemporary accounts of these fictions are much more equivocal in their categorisations of works that were unquestioningly understood as cross-formal and cross-generic. Looking back to the novels of James White, considered in Chapter 1, we see the manner in which late eighteenth-century critics struggled with the formal classifications that are often accepted without question today.