Chapter 4 the SOUTH and CENTRE the South Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Ref No Title Author 1001 Living with Death and Dying Kubler-Ross

Ref No Title Author 1001 Living With Death And Dying Kubler-Ross, Elisabeth 1002 Spiritual Guide for the Separated Laz, Medard 1003 Living Waters None 1004 Catholics and Broken Marriage Catoir, John 1005 Help For the Separated and Divorced Laz, Medard 1006 On the Theology of Death Rahner, Karl 1007 The Road Less Traveled Peck, M Scott 1008 Catholic Almanac None 1009 Visual Talks for Children's Groups Hutchcroft, Vera 1010 Why am I Afraid to Love? Powell, John 1011 On Death and Dying Kubler-Ross, Elisabeth 1012 Islam Williams, John 1013 What is Process Theology? Mellert, Robert 1014 Jesus Christ Liberator Boff, Leonardo 1015 We Were Never Their Age DiGiacomo, James 1016 Who Do You Say that I Am? Ciuba, Edward 1017 Handbook for Today's Catholic None 1018 Portrait of Youth Ministry Harris, Maria 1019 The Pedagogy of Ressurection Bissonnier, Henri 1020 Handbook for Today's Catholic Family None 1021 The Faith that Does Justice Haughey, John 1022 Religion Teacher's Pet Mclntyre, Marie 1023 Constitution on the Church None 1024 Jesus God and Man Brown, Raymond 1025 The Wounded Healer Nouwen, Henri 1026 Should You Ever Feel Guilty? McNulty, Frank J 1027 Who is a Catholic? McBrien, Richard 1028 Candidate's Reflection and Mission Journal Zanzig, Thomas 1029 Human Sexuality Kosnik, Anthony 1030 Successful Single Parenting Bosco, Antoinette 1031 Telling Yourself the Truth Backus, William 1032 The Art of Counseling May, Rollo 1033 Psychological Seduction Kilpatrick, William 1034 Alone with the Alone Maloney, George 1035 Learning to Live Again Sue Carpenter -

The Poem-Book of Gael. Translations from Irish Gaelic Poetry Into English

THE POEM-BOOK OF THE GAEL Mil ,|| líi £ £ O £ Iflíl iiil í 2- ?: Ji JP^ c ^ ^ r:u ^^ ilfil lílU' ^ llfÍJ ^íí Printed bj' Ballantyne, Hanson &>» Co. At the Uallantyne Press, Edinburgh THE POEM-BOOK OF THE GAEL Translations from Irish Gaelic Poetry into English Prose and Verse SELECTED AND EDITED BY ELEANOR HULL AUTHOR OF "THE CUCHULLIN SAGA IN IRISH LITERATURE" "A TEXT-BOOK OF IRISH LITERATURE," ETC. WITH A FRONTISPIECE LONDON CHATTO (^ WINDUS 1912 K^ r [A// rights reservci{\ CONTENTS ( Where not otherwise indicated, the translation or poetic setting is by the ciithor.) PAGE Introduction xv THE SALTAIR NA RANN, OR PSALTER OF THE VERSES í I. The Creation of the Universe . 3 II. The Heavenly Kingdom . II III. The Forbidden Fruit 20 IV. The Fall and Expulsion from Paradise 22 V. The Penance of Adam and Eve 31 VI. The Death of Adam .... 43 ANCIENT PAGAN POEMS The Source of Poetic Inspiration (founded on transla- tion by Whitley Stokes) 53 Amorgen's Song (founded on translation by John MacNeill) 57 25719? viii THE POEM-BOOK OF THE GAEL PAGE The Song of Childbirth . 59 Greeting to the New-born Babe 6i What is Love ? . 62 Summons to Cuchulain . Laegh's Description of Fairy-land 65 The Lamentation of Fand when she is about to leave Cuchulain 69 Mider's Call to Fairy- land 71 The Song of the Fairies . A. H. Leahy 73 The great Lamentation of Deirdre for the Sons of Usna 74 OSSIANIC POETRY First Winter-Song . Alfred Perciv al Graves 81 Second Winter-Song 82 In Praise of May . -

The Tipperary

Walk The Tipperary 10 http://alinkto.me/mjk www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 48 hours in Tipperary This is the Ireland you have been looking for – base yourself in any village or town in County Tipperary, relax with friends (and the locals) and take in all of Tipperary’s natural beauty. Make the iconic Rock of Cashel your first stop, then choose between castles and forest trails, moun- tain rambles or a pub lunch alongside lazy rivers. For ideas and Special Offers visit www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 Walk The Tipperary 10 Challenge We challenge you to walk all of The Tipperary 10 (you can take as long as you like)! Guided Walks Every one of The Tipperary 10 will host an event with a guide and an invitation to join us for refreshments afterwards. Visit us on-line to find out these dates for your diary. For details contact John at 087 0556465. Accommodation Choose from B&Bs, Guest Houses, Hotels, Self-Catering, Youth Hostels & Camp Sites. No matter what kind of accommodation you’re after, we have just the place for you to stay while you explore our beautiful county. Visit us on line to choose and book your favourite location. Golden to the Rock of Cashel Rock of Cashel 1 Photo: Rock of Cashel by Brendan Fennssey Walk Information 1 Golden to the Rock of Cashel Distance of walk: 10km Walk Type: Linear walk Time: 2 - 2.5 hours Level of walk: Easy Start: At the Bridge in Golden Trail End (Grid: S 075 409 OS map no. 66) Cashel Finish: At the Rock of Cashel (Grid: S 012 384 OS map no. -

Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: a True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy

134 Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy endowed university. The Bardic schools and the monastic schools were the universities of their day; they bestowed privileges and Barra Ó Donnabháin Symposium: status on their students and teachers, much as the modern university awards degrees and titles to recipients to practice certain professions. There are few descriptions of the structure and operation of Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A the Bardic schools, but an account contained in the early eighteenth century Memoirs of the Marquis of Clanricarde claims that admission True Exponent of the Bardic WR %DUGLF VFKRROV ZDV FRQÀQHG WR WKRVH ZKR ZHUH GHVFHQGHG from poets and had within their tribe “The Reputation” for poetic Legacy OHDUQLQJ DQG WDOHQW ´7KH TXDOLÀFDWLRQV ÀUVW UHTXLUHG VLF ZHUH Pádraig Ó Cearúill reading well, writing the Mother-tongue, and a strong memory,” according to Clanricarde. With regard to the location of the schools, he asserts that it was necessary that the place should “be in the solitary access of a garden” or “within a set or enclosure far out of the reach of any noise.” The structure containing the Bardic school, we are told, “was snug, low, hot and beds in it at convenient distances, each within a small apartment without much furniture of any kind, save only a table, some seats and a conveniency for he poetry of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin (1748-1784)— cloaths (sic) to hang upon. No windows to let in the day, nor any Tregarded as one of Ireland’s great eighteenth century light at all used but that of candles” according to Clanricarde,2 poets—has endured because of it’s extraordinary metrical whose account is given credence by Bergin3 and Corkery. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

United Irish Cultural Center, Inc. 2700 - 45Th Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94116 Tel: 415-661-2700 Fax: 415-661-8620 E-Mail: [email protected]

Foras Cultuir Gaeil Aontuighthe United Irish Cultural Center, Inc. 2700 - 45th Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94116 Tel: 415-661-2700 Fax: 415-661-8620 E-mail: [email protected] www.irishcentersf.org BOARD MESSAGE Volume XLV No. 11 Dear Members, November 2014 As we come into the month of November, we do so with joy and excitement. October was absolutely wonderful in so many ways! Our San Francisco Giants led the way! The momentum of fall is with us, as we look forward to an absolutely wonderful November and holiday season. Events in November include some significant Sunday activities: a Library Open House on Sunday, November 2nd. Check out the library’s new look and wonderful collection of artifacts; a superb fashion show on Sunday, November 16th, sponsored by the LAOH, Division 2; the Annual Deceased Members’ Mass on Sunday, November 23rd at 10:00 a.m. It is with great respect that we celebrate the lives of those who gave 2014-2015 OFFICERS so much. BOARD OF DIRECTORS I would like to rectify an omission that occurred in the October Bulletin. When thanking the wonderful Building Committee and the incredible volunteers who helped during the August closure of the Judith Kell Center, I left out the name of one of the primary contributors on the Committee: Gerry Cassidy. Apologies President to Gerry and kudo’s to him and those who were mentioned in the October Bulletin for their stellar contribution to our beloved Center. Caitie O’Shea I am bringing my large family and friends to celebrate Thanksgiving with the UICC’s incredible Vice President Thanksgiving dinner. -

The Phylogenealogy of R-L21: Four and a Half Millennia of Expansion and Redistribution

The phylogenealogy of R-L21: four and a half millennia of expansion and redistribution Joe Flood* * Dr Flood is a mathematician, economist and data analyst. He was a Principal Research Scientist at CSIRO and has been a Fellow at a number of universities including Macquarie University, University of Canberra, Flinders University, University of Glasgow, University of Uppsala and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. He was a foundation Associate Director of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. He has been administrator of the Cornwall Y-DNA Geographic Project and several surname projects at FTDNA since 2007. He would like to give credit to the many ‘citizen scientists’ who made this paper possible by constructing the detailed R1b haplotree over the past few years, especially Alex Williamson. 1 ABSTRACT: Phylogenealogy is the study of lines of descent of groups of men using the procedures of genetic genealogy, which include genetics, surname studies, history and social analysis. This paper uses spatial and temporal variation in the subclade distribution of the dominant Irish/British haplogroup R1b-L21 to describe population changes in Britain and Ireland over a period of 4500 years from the early Bronze Age until the present. The main focus is on the initial spread of L21-bearing populations from south-west Britain as part of the Beaker Atlantic culture, and on a major redistribution of the haplogroup that took place in Ireland and Scotland from about 100 BC. The distributional evidence for a British origin for L21 around 2500 BC is compelling. Most likely the mutation originated in the large Beaker colony in south-west Britain, where many old lineages still survive. -

Maths Answers Warm Up

Monday - Maths Answers Warm Up: Doubling Number Chains You have a go: ❖ 3 → 6 → 12 → 24 → 48 → 96 ❖ 2 → 4 → 8 → 16 → 32 → 64 ❖ 5 → 10 → 20 → 40 → 80 → 160 Activity 1: True or False (a) False (b) True (c) False (d) True Activity 2: Answer the following questions based on the bar chart below showing us how many books Cara read over four months. (a) How many books did she read in March? 5 books (b) How many books did she read altogether? 12 books (c) How many months are represented on the chart? 4 months (d) What is the average number of books read per month? 3 books (e) In which month did she read more than the average number of books? March (f) In which months did she read less than the average number of books? February / April Activity 3: Calculating the average 7+11= 18 ➗ 2 = 9 10 + 16 + 13 + 9 = 48 ➗ 4 = 12 64 + 68 + 54 = 186 ➗ 3 =62 Monday - English Answers 1. New Words Obedient: complies with or follows rules Humiliate: to make someone feel ashamed or embarrassed Relinquish: to give up Intimidate: to frighten or scare someone into doing something Questions 1. What breed of dog is Marley? Marley is a labrador 2. What did Marely weigh? Marley weighed 90 pounds 3. What is Marley's owner's name? Marley's owners names was Jenny 4. What advice did the instructor give? The instructor said that they need to gain control over their dog. 5. How did they feel driving home? Why do you think they felt like this? They were embarrassed on the journey because Marley had made a show of them and they felt humiliated by being out of control Dé Luain - Gaeilge ionad siopadóireachta freastalaí sparán praghas airgead cárta creidmheasa Líon na bearnaí: Use these words to fill in the sentences below 1. -

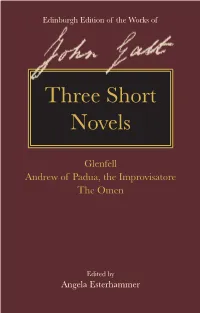

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

Manuel II Palaiologos' Point of View

The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska − University of Łódź, Faculty of Philosophy and History Department of Medieval History, 90-219 Łódź, 27a Kamińskiego St. REVIEWERS Maciej Salamon, Jerzy Strzelczyk INITIATING EDITOR Iwona Gos PUBLISHING EDITOR-PROOFREADER Tomasz Fisiak NATIVE SPEAKERS Kevin Magee, François Nachin TECHNICAL EDITOR Leonora Wojciechowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Katarzyna Turkowska Cover Image: Last_Judgment_by_F.Kavertzas_(1640-41) commons.wikimedia.org Printed directly from camera-ready materials provided to the Łódź University Press This publication is not for sale © Copyright by Małgorzata Dąbrowska, Łódź 2017 © Copyright for this edition by Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź 2017 Published by Łódź University Press First edition. W.07385.16.0.M ISBN 978-83-8088-091-7 e-ISBN 978-83-8088-092-4 Printing sheets 20.0 Łódź University Press 90-131 Łódź, 8 Lindleya St. www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] tel. (42) 665 58 63 CONTENTS Preface 7 Acknowledgements 9 CHAPTER ONE The Palaiologoi Themselves and Their Western Connections L’attitude probyzantine de Saint Louis et les opinions des sources françaises concernant cette question 15 Is There any Room on the Bosporus for a Latin Lady? 37 Byzantine Empresses’ Mediations in the Feud between the Palaiologoi (13th–15th Centuries) 53 Family Ethos at the Imperial Court of the Palaiologos in the Light of the Testimony by Theodore of Montferrat 69 Ought One to Marry? Manuel II Palaiologos’ Point of View 81 Sophia of Montferrat or the History of One Face 99 “Vasilissa, ergo gaude...” Cleopa Malatesta’s Byzantine CV 123 Hellenism at the Court of the Despots of Mistra in the First Half of the 15th Century 135 4 • 5 The Power of Virtue.