The Gothic Novel in Ireland, C. 1760–1829

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

A Natural History of the Romance Novel

A romance novel is a work ofprosefiction that tells the story of the courtship and betrothal ofone or more heroines. As this definition is neither widely known nor accepted, it ' -requires no little defense as well as some teasing out of dis- tinctions between the term put forward here, "romance novel," and terms in widespread use, such as .''E'&&nq~and "novel." I begin with the broadest term, "roman$< . ' The term "romance" is confusing~~iiiclp~~,meaning one ' .* - thing in r suncy- of me&eval lit entire& &&cc, in a cbntmhporary store for r copy of the h&mt Dartbur axit$:& &k will take you m the 'literacure" $t&on: a glance a; prdksintroduction will inform you that Malory's prose a~$$t,~4:f King Arthur is called a "romance." Ask for a roman<L d$he clerk will take t y. '%- you to the (generally) large section G& & &e stocked with Harlequins, Silhouettes and single-title releases by writers such as Nora Roberts, Amanda Quick, and Janet Dailey. Can Mal- 07's Mortc Dartbur and Quick's Dcctptwn both be romances? , They can be and are, but only Dcctption is also a romance novel . as I am defining the term here. Robert Ellrich hazards a definition of the old, encompassing term "romance": "the story of iridividual human beings pursu- :.hg their precarious existence with+ the circumscription of ~d,moral, and various other hs-worldly problems. the ce . means to show the &r what steps must be taken to reach a desired goal, sqresented often though not m the guise of a spouse" @f4-75). -

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

Chaotic Descriptor Table

Castle Oldskull Supplement CDT1: Chaotic Descriptor Table These ideas would require a few hours’ the players back to the temple of the more development to become truly useful, serpent people, I decide that she has some but I like the direction that things are going backstory. She’s an old jester-bard so I’d probably run with it. Maybe I’d even treasure hunter who got to the island by redesign dungeon level 4 to feature some magical means. This is simply because old gnome vaults and some deep gnome she’s so far from land and trade routes that lore too. I might even tie the whole it’s hard to justify any other reason for her situation to the gnome caves of C. S. Lewis, to be marooned here. She was captured by or the Nome King from L. Frank Baum’s the serpent people, who treated her as Ozma of Oz. Who knows? chattel, but she barely escaped. She’s delirious, trying to keep herself fed while she struggles to remember the command Example #13: word for her magical carpet. Malamhin of the Smooth Brow has some NPC in the Wilderness magical treasures, including a carpet of flying, a sword, some protection from serpents thingies (scrolls, amulets?) and a The PCs land on a deadly magical island of few other cool things. Talking to the PCs the serpent people, which they were meant and seeing their map will slowly bring her to explore years ago and the GM promptly back to her senses … and she wants forgot about it. -

Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2011 Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas Frans Weiser University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Weiser, Frans, "Con-Scripting the Masses: False Documents and Historical Revisionism in the Americas" (2011). Open Access Dissertations. 347. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/347 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2011 Program of Comparative Literature © Copyright 2011 by Frans-Stephen Weiser All Rights Reserved CON-SCRIPTING THE MASSES: FALSE DOCUMENTS AND HISTORICAL REVISIONISM IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation Presented by FRANS-STEPHEN WEISER Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________________ David Lenson, Chair _______________________________________________ -

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto 1 The Sadleir-Black Collection 2 2 The Microfilm Collection 7 3 Gothic Origins 11 4 Gothic Revolutions 15 5 The Northanger Novels 20 6 Radcliffe and her Imitators 23 7 Lewis and her Followers 27 8 Terror and Horror Gothic 31 9 Gothic Echoes / Gothic Labyrinths 33 © Peter Otto and Adam Matthew Publications Ltd. Published in Gothic Fiction: A Guide, by Peter Otto, Marie Mulvey-Roberts and Alison Milbank, Marlborough, Wilt.: Adam Matthew Publications, 2003, pp. 11-57. Available from http://www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/gothic_fiction/Contents.aspx Deposited to the University of Melbourne ePrints Repository with permission of Adam Matthew Publications - http://eprints.unimelb.edu.au All rights reserved. Unauthorised Reproduction Prohibited. 1. The Sadleir-Black Collection It was not long before the lust for Gothic Romance took complete possession of me. Some instinct – for which I can only be thankful – told me not to stray into 'Sensibility', 'Pastoral', or 'Epistolary' novels of the period 1770-1820, but to stick to Gothic Novels and Tales of Terror. Michael Sadleir, XIX Century Fiction It seems appropriate that the Sadleir-Black collection of Gothic fictions, a genre peppered with illicit passions, should be described by its progenitor as the fruit of lust. Michael Sadleir (1888-1957), the person who cultivated this passion, was a noted bibliographer, book collector, publisher and creative writer. Educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford, Sadleir joined the office of the publishers Constable and Company in 1912, becoming Director in 1920. He published seven reasonably successful novels; important biographical studies of Trollope, Edward and Rosina Bulwer, and Lady Blessington; and a number of ground-breaking bibliographical works, most significantly Excursions in Victorian Bibliography (1922) and XIX Century Fiction (1951). -

The Intellectual Functions of Gothic Fiction

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1977 FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION PAUL LEWIS Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEWIS, PAUL, "FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION" (1977). Doctoral Dissertations. 1160. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Partitive Article

Book Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.) Abstract The volume Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article, edited by Tabea Ihsane, focuses on different aspects of the distribution, semantics, and internal structure of nominal constituents with a “partitive article” in its indefinite interpretation and of potentially corresponding bare nouns. It further deals with diachronic issues, such as grammaticalization and evolution in the use of “partitive articles”. The outcome is a snapshot of current research into “partitive articles” and the way they relate to bare nouns, in a cross-linguistic perspective and on new data: the research covers noteworthy data (fieldwork data and corpora) from Standard languages - like French and Italian, but also German - to dialectal and regional varieties, including endangered ones like Francoprovençal. Reference IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.). Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article. Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020 DOI : 10.1163/9789004437500 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:145202 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article - 978-90-04-43750-0 Downloaded from PubFactory at 10/29/2020 05:18:23PM via Bibliotheque de Geneve, Bibliotheque de Geneve, University of Geneva and Universite de Geneve Syntax & Semantics Series Editor Keir Moulton (University of Toronto, Canada) Editorial Board Judith Aissen (University of California, Santa Cruz) – Peter Culicover (The Ohio State University) – Elisabet Engdahl (University of Gothenburg) – Janet Fodor (City University of New York) – Erhard Hinrichs (University of Tubingen) – Paul M. -

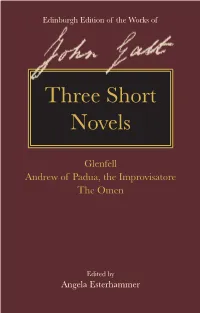

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Everything You Wanted to Know About Transgender Studies but Were Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve

humanities Article “More and More Fond of Reading”: Everything You Wanted to Know about Transgender Studies but Were Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve Desmond Huthwaite Faculty of English, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1TN, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Clara Reeve’s (1729–1807) Gothic novel The Old English Baron is a node for contemplating two discursive exclusions. The novel, due to its own ambiguous status as a gendered “body”, has proven a difficult text for discourse on the Female Gothic to recognise. Subjected to a temperamental dialectic of reclamation and disavowal, The Old English Baron can be made to speak to the (often) subordinate position of Transgender Studies within the field of Queer Studies, another relationship predicated on the partial exclusion of undesirable elements. I treat the unlikely transness of Reeve’s body of text as an invitation to attempt a trans reading of the bodies within the text. Parallel to this, I de- velop an attachment genealogy of Queer and Transgender Studies that reconsiders essentialism—the kind both practiced by Female Gothic studies and also central to the logic of Reeve’s plot—as a fantasy that helps us distinguish where a trans reading can depart from a queer one, suggesting that the latter is methodologically limited by its own bad feelings towards the former. Keywords: Clara Reeve; Female Gothic; trans; queer; gender; embodiment The “literary offspring of the Castle of Otranto” had, and continues to have, something Citation: Huthwaite, Desmond. 2021. of a difficult birth.1 In its first year of life, the text was christened twice (titled The Champion “More and More Fond of Reading”: of Virtue in 1777, then Old English Baron in a revised 1778 edition); described alternately Everything You Wanted to Know as a transcription, a translation, a history, a romance, and (most enduringly) a “Gothic about Transgender Studies but Were story”; attributed to “the editor of the PHOENIX” and then to Clara Reeve; and subjected Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve. -

An Oeo^Rejne

an oeo^RejNe Tsfte Monthly Magazine of Jin Qomunn <§aidhealaeh Volume XVI. Oct., 1920, to Sept., 1921. inclusive. AN COMUNN GAIDHEALACH 114 West Campfeli. Street, Glasgow. ^ CONTENTS. GAELIC DEPARTMENT. PAGE Am Fear Deasachaidh— Adhartachadh agus Foghlum na Gaidhlig 85 Oraid a’ Chinn Suidhe, - - - 1 Am biodh oibrichean mora chum maith Am Foghar agus an t-Samhain, - 17 na Gaidhealtaohd, - - - - 117 An Geamhradh, - - - - - 33 Ardachadh na Gaidhlig agus na Sochair- A’ Bhliadhna Ur, - - - - 49 ean a gheibh sinn troimh eolas oirre, 162 Gaidheil agus Fearann, - - - 65 Blar Chairinnis, ----- 67 An t-Earrach, ----- 81 Ceilidh nan Gaidheal, - - ' - - 123 Croiteirean an la an diugh, - - 97 Cruinne Eolas: Alba, - - - 38, 77 Meuran a’ Chomuinn, - - - 113 Dealbh Chluich, - - - - 41, 53 Spiorad na h-aimsir a tha ann, - 129 Eoghann Mac an Toisich agus na Leas na Gaidhealtaohd, - - - 145 Cuimeinich, ----- 100 Saothair a’ Chomuinn Ghaidhealaich, 161 Fas Gniomhachais na Gaidhealtachd, - 148 Seachd Bliadhna ’n ama so, - - 177 Fear a’ Chbta Shlibistich liath-ghlais, - 25 A’ Bheurla Shasunnach mar a Ghnach- Latha Blar Shron Chlachain, - - - 84 aiehear i an Albainn mu Dheas, Mar a thainig a latha fhein air Maol 132, 175, 179 Innis, ------ 181 Bardachd. PAGE Alba, - 61 Feasgar 7sa Ghleann, 13 Failte do Bharraidh, 83 Tir nan Og, - 72 Bardachd agus Ceol. PAGE PAGE A’ Chailinn tha tamh mu Loch Eite, 121 Bodach na Gealaich, 58 A’ Chaora Cheann-fhionn, 93 Caisteal a’ Ghlinne, 154 An Gaidheal air leaba-bais, - 73 Dh’ fhalbh mo leannan fhein, - 104 3 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT.