An Outline of the Succession and Migration of Non-Crinoid Pelmatozoan Faunas in the Lower Paleozoic of Scandinavia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paleoecology and Biogeography of Ordovician Edrioasteroids

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2011 The Paleoecology and Biogeography of Ordovician Edrioasteroids Rene Anne Lewis University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Rene Anne, "The Paleoecology and Biogeography of Ordovician Edrioasteroids. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1094 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Rene Anne Lewis entitled "The Paleoecology and Biogeography of Ordovician Edrioasteroids." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geology. Michael L. McKinney, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Colin D. Sumrall, Linda C. Kah, Arthur C. Echternacht Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) THE PALEOECOLOGY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF ORDOVICIAN EDRIOASTEROIDS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville René Anne Lewis August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by René Anne Lewis All rights reserved. -

PUBLICATIONS by JAMES SPRINKLE 1965 -- Sprinkle, James

PUBLICATIONS BY JAMES SPRINKLE 1965 -- Sprinkle, James. 1965. Stratigraphy and sedimentary petrology of the lower Lodgepole Formation of southwestern Montana. M.I.T. Department of Geology and Geophysics, unpublished Senior Thesis, 29 p. (see #56 and 66 below) 1966 1. Sprinkle, James and Gutschick, R. C. 1966. Blastoids from the Sappington Formation of southwest Montana (Abst.). Geological Society of America Special Paper 87:163-164. 1967 2. Sprinkle, James and Gutschick, R. C. 1967. Costatoblastus, a channel fill blastoid from the Sappington Formation of Montana. Journal of Paleon- tology, 41(2):385-402. 1968 3. Sprinkle, James. 1968. The "arms" of Caryocrinites, a Silurian rhombiferan cystoid (Abst.). Geological Society of America Special Paper 115:210. 1969 4. Sprinkle, James. 1969. The early evolution of crinozoan and blastozoan echinoderms (Abst.). Geological Society of America Special Paper 121:287-288. 5. Robison, R. A. and Sprinkle, James. 1969. A new echinoderm from the Middle Cambrian of Utah (Abst.). Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 1(5):69. 6. Robison, R. A. and Sprinkle, James. 1969. Ctenocystoidea: new class of primitive echinoderms. Science, 166(3912):1512-1514. 1970 -- Sprinkle, James. 1970. Morphology and Evolution of Blastozoan Echino- derms. Harvard University Department of Geological Sciences, unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, 433 p. (see #8 below) 1971 7. Sprinkle, James. 1971. Stratigraphic distribution of echinoderm plates in the Antelope Valley Limestone of Nevada and California. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 750-D (Geological Survey Research 1971):D89-D98. 1973 8. Sprinkle, James. 1973. Morphology and Evolution of Blastozoan Echino- derms. Harvard University, Museum of Comparative Zoology Special Publication, 283 p. -

001-012 Primeras Páginas

PUBLICACIONES DEL INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO. Nº 9 ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES planeta tierra Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and Ciencias de la Tierra para la Sociedad D. García-Bellido 9 788478 407590 MINISTERIO MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN E INNOVACIÓN ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido Instituto Geológico y Minero de España Madrid, 2008 Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO, Nº 9 INTERNATIONAL TRILOBITE CONFERENCE (4. 2008. Toledo) Advances in trilobite research: Fourth International Trilobite Conference, Toledo, June,16-24, 2008 / I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido, eds.- Madrid: Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 2008. 448 pgs; ils; 24 cm .- (Cuadernos del Museo Geominero; 9) ISBN 978-84-7840-759-0 1. Fauna trilobites. 2. Congreso. I. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, ed. II. Rábano,I., ed. III Gozalo, R., ed. IV. García-Bellido, D., ed. 562 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. References to this volume: It is suggested that either of the following alternatives should be used for future bibliographic references to the whole or part of this volume: Rábano, I., Gozalo, R. and García-Bellido, D. (eds.) 2008. Advances in trilobite research. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 9. -

Contributions in BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY

MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions In BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 51 November 29, 1982 A Compendium of Fossil Marine Families J. John Sepkoski, Jr. MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions in BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 51 November 29, 1982 A COMPENDIUM OF FOSSIL MARINE FAMILIES J. JOHN SEPKOSKI, JR. Department of the Geophysical Sciences University of Chicago REVIEWERS FOR THIS PUBLICATION: Robert Gernant, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee David M. Raup, Field Museum of Natural History Frederick R. Schram, San Diego Natural History Museum Peter M. Sheehan, Milwaukee Public Museum ISBN 0-893260-081-9 Milwaukee Public Museum Press Published by the Order of the Board of Trustees CONTENTS Abstract ---- ---------- -- - ----------------------- 2 Introduction -- --- -- ------ - - - ------- - ----------- - - - 2 Compendium ----------------------------- -- ------ 6 Protozoa ----- - ------- - - - -- -- - -------- - ------ - 6 Porifera------------- --- ---------------------- 9 Archaeocyatha -- - ------ - ------ - - -- ---------- - - - - 14 Coelenterata -- - -- --- -- - - -- - - - - -- - -- - -- - - -- -- - -- 17 Platyhelminthes - - -- - - - -- - - -- - -- - -- - -- -- --- - - - - - - 24 Rhynchocoela - ---- - - - - ---- --- ---- - - ----------- - 24 Priapulida ------ ---- - - - - -- - - -- - ------ - -- ------ 24 Nematoda - -- - --- --- -- - -- --- - -- --- ---- -- - - -- -- 24 Mollusca ------------- --- --------------- ------ 24 Sipunculida ---------- --- ------------ ---- -- --- - 46 Echiurida ------ - --- - - - - - --- --- - -- --- - -- - - --- -

Reinterpretation of the Enigmatic Ordovician Genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata)

Reinterpretation of the enigmatic Ordovician genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata). Emeric Gillet, Bertrand Lefebvre, Véronique Gardien, Emilie Steimetz, Christophe Durlet, Frédéric Marin To cite this version: Emeric Gillet, Bertrand Lefebvre, Véronique Gardien, Emilie Steimetz, Christophe Durlet, et al.. Reinterpretation of the enigmatic Ordovician genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata).. Zoosymposia, Magnolia Press, 2019, 15 (1), pp.44-70. 10.11646/zoosymposia.15.1.7. hal-02333918 HAL Id: hal-02333918 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02333918 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Reinterpretation of the Enigmatic Ordovician Genus Bolboporites 2 (Echinodermata) 3 4 EMERIC GILLET1, BERTRAND LEFEBVRE1,3, VERONIQUE GARDIEN1, EMILIE 5 STEIMETZ2, CHRISTOPHE DURLET2 & FREDERIC MARIN2 6 7 1 Université de Lyon, UCBL, ENSL, CNRS, UMR 5276 LGL-TPE, 2 rue Raphaël Dubois, F- 8 69622 Villeurbanne, France 9 2 Université de Bourgogne - Franche Comté, CNRS, UMR 6282 Biogéosciences, 6 boulevard 10 Gabriel, F-2100 Dijon, France 11 3 Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 12 13 Abstract 14 Bolboporites is an enigmatic Ordovician cone-shaped fossil, the precise nature and systematic affinities of 15 which have been controversial over almost two centuries. -

Pennsylvanian Crinoids of New Mexico

Pennsylvanian crinoids of New Mexico Gary D. Webster, Department of Geology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, and Barry S. Kues, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 Abstract north of Alamogordo; (2) Morrowan and groups present on the outcrop were sam- Atokan specimens from the La Pasada For- pled, often repeatedly over the years. Crinoids from each of the five Pennsylvanian mation in the Santa Fe area; and (3) a mid- These collections, reposited at the Univer- epochs are described from 26 localities in dle Desmoinesian species from the Alami- sity of New Mexico (UNM), testify to the New Mexico. The crinoid faunas occupied tos Formation, north of Pecos. Bowsher rarity of identifiable crinoid cups and diverse shelf environments around many intermontane basins of New Mexico during and Strimple (1986) described 15 late crowns in these assemblages, even in cases the Pennsylvanian. The crinoids described Desmoinesian or early Missourian crinoid where crinoid stem elements are common. here include 29 genera, 39 named species, species (several not named) from near the In nearly all collections, crinoid cups rep- and at least nine unnamed species, of which top of the Bug Scuffle Member of the Gob- resent only a small fraction of 1% of the one genus and 15 named species are new. bler Formation south of Alamogordo in the total identifiable specimens. The only This report more than doubles the number of Sacramento Mountains. Kietzke (1990) exception is the fauna from the Missourian previously known Pennsylvanian crinoid illustrated a Desmoinesian microcrinoid Sol se Mete Member, Wild Cow Formation, species from New Mexico; 17 of these species from the Flechado Formation near Talpa. -

Origin and Significance of Lovén's Law in Echinoderms

Journal of Paleontology, 94(6), 2020, p. 1089–1102 Copyright © 2020, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2020.31 Origin and significance of Lovén’s Law in echinoderms Christopher R. C. Paul1 and Frederick H. C. Hotchkiss2 1School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK <[email protected]> 2Marine and Paleobiological Research Institute, P.O. Box 1016, Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, USA 02568 <hotchkiss@MPRInstitute. org> Abstract.—Lovén’s Law described the position of larger basicoronal ambulacral plates in echinoids. The smaller basi- coronal plates form first in ontogeny. We restate Lovén’s Law to describe the position of first ambulacral plates using Carpenter’s ambulacra and left (L) or right (R) as: AR, BL, CR, DL, ER, with EA the pair of ambulacra both identical and adjacent. First ambulacral plates of the Cambrian edrioasteroid, Walcottidiscus, code identically. The transition from a tri-radiate 1-1-1 pattern to the 2-1-2 ambulacral pattern of Walcottidiscus and other pentaradiate Paleozoic echinoderms results in Lovén’s Law. This provides an hypothesis for the origin of Lovén’s Law and predicts its widespread occurrence among echinoderm classes. The ‘BD different’ pattern of primary brachioles in pentaradiate glyptocystitoid Rhombifera results from subterminal branching of the ambulacra. The ontogenetic sequence was triradiate, then lateral ambulacra bifurcated, and finally second brachioles developed. -

The Early History of the Metazoa—A Paleontologist's Viewpoint

ISSN 20790864, Biology Bulletin Reviews, 2015, Vol. 5, No. 5, pp. 415–461. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2015. Original Russian Text © A.Yu. Zhuravlev, 2014, published in Zhurnal Obshchei Biologii, 2014, Vol. 75, No. 6, pp. 411–465. The Early History of the Metazoa—a Paleontologist’s Viewpoint A. Yu. Zhuravlev Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, per. Pyzhevsky 7, Moscow, 7119017 Russia email: [email protected] Received January 21, 2014 Abstract—Successful molecular biology, which led to the revision of fundamental views on the relationships and evolutionary pathways of major groups (“phyla”) of multicellular animals, has been much more appre ciated by paleontologists than by zoologists. This is not surprising, because it is the fossil record that provides evidence for the hypotheses of molecular biology. The fossil record suggests that the different “phyla” now united in the Ecdysozoa, which comprises arthropods, onychophorans, tardigrades, priapulids, and nemato morphs, include a number of transitional forms that became extinct in the early Palaeozoic. The morphology of these organisms agrees entirely with that of the hypothetical ancestral forms reconstructed based on onto genetic studies. No intermediates, even tentative ones, between arthropods and annelids are found in the fos sil record. The study of the earliest Deuterostomia, the only branch of the Bilateria agreed on by all biological disciplines, gives insight into their early evolutionary history, suggesting the existence of motile bilaterally symmetrical forms at the dawn of chordates, hemichordates, and echinoderms. Interpretation of the early history of the Lophotrochozoa is even more difficult because, in contrast to other bilaterians, their oldest fos sils are preserved only as mineralized skeletons. -

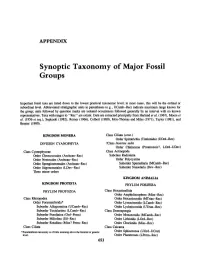

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Athenacrinus N. Gen. and Other Early Echinoderm Taxa Inform Crinoid

Athenacrinus n. gen. and other early echinoderm taxa inform crinoid origin and arm evolution Thomas Guensburg, James Sprinkle, Rich Mooi, Bertrand Lefebvre, Bruno David, Michel Roux, Kraig Derstler To cite this version: Thomas Guensburg, James Sprinkle, Rich Mooi, Bertrand Lefebvre, Bruno David, et al.. Athenacri- nus n. gen. and other early echinoderm taxa inform crinoid origin and arm evolution. Journal of Paleontology, Paleontological Society, 2020, 94 (2), pp.311-333. 10.1017/jpa.2019.87. hal-02405959 HAL Id: hal-02405959 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02405959 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Journal of Paleontology, 94(2), 2020, p. 311–333 Copyright © 2019, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2019.87 Athenacrinus n. gen. and other early echinoderm taxa inform crinoid origin and arm evolution Thomas E. -

Athenacrinus N. Gen. and Other Early Echinoderm Taxa Inform Crinoid Origin and Arm Evolution

Journal of Paleontology, 94(2), 2020, p. 311–333 Copyright © 2019, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2019.87 Athenacrinus n. gen. and other early echinoderm taxa inform crinoid origin and arm evolution Thomas E. Guensburg,1 James Sprinkle,2 Rich Mooi,3 Bertrand Lefebvre,4 Bruno David,5,6 Michel Roux,7 and Kraig Derstler8 1IRC, Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA <tguensburg@fieldmuseum.org> 2Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas, 1 University Station C1100, Austin, Texas 78712-0254, USA <[email protected]> 3Department of Invertebrate Zoology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA <[email protected]> 4UMR 5276 LGLTPE, Université Claude Bernard, Lyon 1, France <[email protected]> 5Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France <[email protected]> 6UMR CNRS 6282 Biogéosciences, Université de Bourgogne Franche-Comté, 21000 Dijon, France <[email protected]> 7Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, UMR7205 ISYEB MNHN-CNRS-UMPC-EPHE, Département Systématique et Évolution, CP 51, 57 Rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France <[email protected]> 8Department of Earth and Environmental Studies, University of New Orleans, 2000 Lake Shore Drive, New Orleans, Louisiana 70148, USA <[email protected]> Abstract.—Intermediate morphologies of a new fossil crinoid shed light on the pathway by which crinoids acquired their distinctive arms. -

An Introduction to the Study of Fossils (Plants and Animals)

ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY AT CORNELL UNIVERSITY THE GIFT OF Mrs. Winthrop Crane III DATE DUE IPPffl*^ HfflHHIfff IGOO APR i 3 IINTEO IN U.S.A. Cornell University Library QE 713.S55 An introduction to the study of fossils 3 1924 001 613 599 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 924001 61 3599 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF FOSSILS THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO - DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN &: CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF FOSSILS (PLANTS AND ANIMALS) BY HERVEY WOODBURN SHIMER, A.M., Ph.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF PALEONTOLOGY IN THE MASSA- CHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wefa gorfe THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1924 All rights reseinjed -713 Copyright, 1914, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1914. J. 8. Gushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Masa., U.S.A. MY WIFE COMRADE AND COLLABORATOR THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED PREFACE This little volume has grown out of a need experienced by the author during fifteen years of teaching paleontology. He has found that students come to the subject either with very little previous training in biology, or at best with a training which has not been along the lines that would definitely aid them in understanding fossils. Too often fossils are looked upon merely as bits of stone, differing only in form from the rocks in which they are embedded.