Great Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

James III and VIII

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. James III and VIII Professor Edward Corp Université de Toulouse Bonnie Prince Charlie Entering the Ballroom at Holyroodhouse before 30 Apr 1892. Royal Collection Trust/ ©Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018 EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The life story of James III and VIII is mainly contained Germain-en-Laye in France, James had good reason to within the Stuart Papers in the Royal Archives at be confident that he would one day be restored to the Windsor Castle. They contain thousands of documents thrones of his father. In the second (1719-66), when he in hundreds of volumes giving details of his political mainly lived at Rome, he increasingly doubted and and personal correspondence, of his finances, and of eventually knew that he would never be restored. The the management of his court. Yet it is important to turning point came during the five years from the recognise that the Stuart Papers provide a summer of 1714 to the summer of 1719, when James comprehensive account of the king's life only from the experienced a series of major disappointments and beginning of 1716, when he was 27 years old. They tell reverses which had a profound effect on his us very little about the period from his birth at personality. Whitehall Palace in June 1688 until he reached the age He had a happy childhood at Saint-Germain, where he of 25 in 1713, and not much about the next two years was recognised as the Prince of Wales and then, after from 1713 to the end of 1715. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

New Albion P1

State of California The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 2 of 30 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Site of New Albion P1. Other Identifier: ____ *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County Marin and (P2c, P2e, and P2b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad Date T ; R ; of of Sec ; B.M. c. Address 1 Drakes Beach Road City Inverness Zip 94937 d. UTM: (Give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone , mE/ mN e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, decimal degrees, etc., as appropriate) Site bounded by 38.036° North latitude, -122.590° West longitude, 38.030° North ° latitude, and -122.945 West longitude. *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) Site of Francis Drake’s 1579 encampment called “New Albion” by Drake. Includes sites of Drake’s fort, the careening of the Golden Hind, the abandonment of Tello’s bark, and the meetings with the Coast Miwok peoples. Includes Drake’s Cove as drawn in the Hondius Broadside map (ca. 1595-1596) which retains very high integrity. P5a. Photograph or Drawing (Photograph required for buildings, structures, and objects.) Portus Novae Albionis *P3b. Resource Attributes: (List attributes and codes) AH16-Other Historic Archaeological Site DPR 523A (9/2013) *Required information State of California The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 3 of 30 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Site of New Albion P1. -

Key Stage 3 Early Modern Britain

KS3 Knowing History Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide Key Stage 3 Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide Robert Peal Text © Robert Peal 2016; Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Limited 2016 1 KS3 Knowing History Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide William Collins’ dream of knowledge for all began with the publication of his first book in 1819. A self-educated mill worker, he not only enriched millions of lives, but also founded a flourishing publishing house. Today, staying true to this spirit, Collins books are packed with inspiration, innovation and practical expertise. They place you at the centre of a world of possibility and give you exactly what you need to explore it. Collins. Freedom to teach Published by Collins An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers The News Building 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF Text © Robert Peal 2016 Design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Robert Peal asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the Publisher. This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the Publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Emigration from Great Britain

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations Volume Author/Editor: Walter F. Willcox, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-017-5 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/will31-1 Publication Date: 1931 Chapter Title: Emigration from Great Britain Chapter Author: C. E. Snow Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5111 Chapter pages in book: (p. 237 - 260) PART III STUDIES OF NATIONALEMIGRATION CURRENTS CHAPTER IX EMIGRATION FROM GREAT BRITAIN.' By DR. C. E. SNOW. General Concerning emigration from Great Britain prior to 1815, only fragmentary statistics are available, for before that date no regular attempt was made to measure the outflow of population.For some years before the treaty of peace with France, under which Canada in 1763 became a colony of the United Kingdom, a certain number of emigrants from Great Britain to the British North Amer- ican colonies were reported, but no reliable figures are available. During the five years 1769—1774 there was an emigration, probably approaching 10,000 persons per annum,2 from Scotland to North America, and substantial numbers also left England for the same destination.It has been estimated by Johnson3 that during the first decade of the nineteenth century the annual emigration from the whole of the United Kingdom to the American Continent ex- ceeded 20,000 persons, the majority going from the Highlands of Scotland and from Ireland. Emigration can be considered from two distinct aspects: (a) from the point of view of the force attracting people to other countries; (b) from the point of view of the force expelling people from their own country. -

H 955 Great Britain

Great Britain H 955 BACKGROUND: The heading Great Britain is used in both descriptive and subject cataloging as the conventional form for the United Kingdom, which comprises England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. This instruction sheet describes the usage of Great Britain, in contrast to England, as a subject heading. It also describes the usage of Great Britain, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as geographic subdivisions. 1. Great Britain vs. England as a subject heading. In general assign the subject heading Great Britain, with topical and/or form subdivisions, as appropriate, to works about the United Kingdom as a whole. Assign England, with appropriate subdivision(s), to works limited to that country. Exception: Do not use the subdivisions BHistory or BPolitics and government under England. For a work on the history, politics, or government of England, assign the heading Great Britain, subdivided as required for the work. References in the subject authority file reflect this practice. Use the subdivision BForeign relations under England only in the restricted sense described in the scope note under EnglandBForeign relations in the subject authority file. 2. Geographic subdivision. a. Great Britain. Assign Great Britain directly after topics for works that discuss the topic in relation to Great Britain as a whole. Example: Title: History of the British theatre. 650 #0 $a Theater $z Great Britain $x History. b. England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Assign England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, or Wales directly after topics for works that limit their discussion to the topic in relation to one of the four constituent countries of Great Britain. -

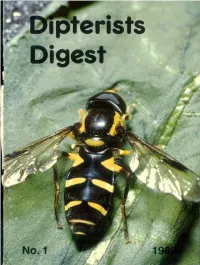

Ipterists Digest

ipterists Digest Dipterists’ Digest is a popular journal aimed primarily at field dipterists in the UK, Ireland and adjacent countries, with interests in recording, ecology, natural history, conservation and identification of British and NW European flies. Articles may be of any length up to 3000 words. Items exceeding this length may be serialised or printed in full, depending on the competition for space. They should be in clear concise English, preferably typed double spaced on one side of A4 paper. Only scientific names should be underlined- Tables should be on separate sheets. Figures drawn in clear black ink. about twice their printed size and lettered clearly. Enquiries about photographs and colour plates — please contact the Production Editor in advance as a charge may be made. References should follow the layout in this issue. Initially the scope of Dipterists' Digest will be:- — Observations of interesting behaviour, ecology, and natural history. — New and improved techniques (e.g. collecting, rearing etc.), — The conservation of flies and their habitats. — Provisional and interim reports from the Diptera Recording Schemes, including provisional and preliminary maps. — Records of new or scarce species for regions, counties, districts etc. — Local faunal accounts, field meeting results, and ‘holiday lists' with good ecological information/interpretation. — Notes on identification, additions, deletions and amendments to standard key works and checklists. — News of new publications/references/iiterature scan. Texts concerned with the Diptera of parts of continental Europe adjacent to the British Isles will also be considered for publication, if submitted in English. Dipterists Digest No.1 1988 E d ite d b y : Derek Whiteley Published by: Derek Whiteley - Sheffield - England for the Diptera Recording Scheme assisted by the Irish Wildlife Service ISSN 0953-7260 Printed by Higham Press Ltd., New Street, Shirland, Derby DE5 6BP s (0773) 832390. -

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History1

The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXV, 1: No. 219: April 2006, 1–27 MATTHEW H. HAMMOND Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish history1 ABSTRACT Historians have long tended to define medieval Scottish society in terms of interactions between ethnic groups. This approach was developed over the course of the long nineteenth century, a formative period for the study of medieval Scotland. At that time, many scholars based their analysis upon scientific principles, long since debunked, which held that medieval ‘peoples’ could only be understood in terms of ‘full ethnic packages’. This approach was combined with a positivist historical narrative that defined Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Normans as the harbingers of advances in Civilisation. While the prejudices of that era have largely faded away, the modern discipline still relies all too often on a dualistic ethnic framework. This is particularly evident in a structure of periodisation that draws a clear line between the ‘Celtic’ eleventh century and the ‘Norman’ twelfth. Furthermore, dualistic oppositions based on ethnicity continue, particu- larly in discussions of law, kingship, lordship and religion. Geoffrey Barrow’s Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, first published in 1965 and now available in the fourth edition, is proba- bly the most widely read book ever written by a professional historian on the Middle Ages in Scotland.2 In seeking to introduce the thirteenth century to such a broad audience, Barrow depicted Alexander III’s Scot- land as fundamentally -

British Geography 1918-1945

British Geography 1918-1945 British Geography 1918-1945 edited by ROBERT W. STEEL The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VUI in 1534. The University has printed and published continuously since 1584. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge London New York New Rochelle Melbourne Sydney CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www. Cambridge. org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521247900 © Cambridge University Press 1987 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1987 This digitally printed version 2008 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data British geography 1918-1945. Includes index. 1. Geography - Great Britain. I. Steel, Robert W. (Robert Walter), 1915- G99.B75 1987 910,941 87-6549 ISBN 978-0-521-24790-0 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-06771-3 paperback Contents Preface ROBERT W. STEEL vii 1 The beginning and the end ROBERT W. STEEL I 2 Geography during the inter-war years T. w. FREEMAN 9 3 Geography in the University of Wales, 1918-1948 E. G. BOWEN 25 4 Geography at Birkbeck College, University of London, with particular reference to J. F. Unstead and E. -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde.