6 ^ ® ® German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Antiaircraft Artillery and Its Use, and at the Same Time to Furnish U

U 15 U635 no. 10 c.3 =~ UNCuSSIFIED MILITARY INTELLIGENCE SPECIAL SERIES SERVICE No. 10 WAR DEPARTMENT MIS 461 WASHINGTON, February 8, 1943 NOTICE 1. Publication of Special Series is for the purpose of providing officers with reasonably confirmed information from official and other reliable sources. 2. Nondivisional units are being supplied with copies on a basis similar to the approved distribution for divisional commands, as follows: INr DIV CAV DIv ARMD Div Div Hq 8 Div Hq 8 Div Hq 11 Rcn Tr 2 OrdCo 2 Rcn Bn 7 Sig Co 2 Sig Tr 2 Engr Bn 7 Engr Bn 7 Rcn Sq 7 Med Bn 7 Med Bn 7 Engr Sq 7 Maint Bn 7 QM Co 7 MedSq 7 Sup Bn 7 Hq Inf Regt, 6 each 18 QM Sq 7 Div Tn Hq 8 Inf Bn, 7 eatch 63 IHq Cav Brig, 3 each 6 Armd Regt, 25 each 50 lIq Div Arty 8 Cav Regt, 20 each 80 FA Bn, 7 each 21 FA Bn, 7 each 28 fHq Div Arty 3 Inf Regt 25 -- FA Bn, 7 each 21 -- 150 ---- 150 150 Distribution to air units is being made by the A-2 of Army Air Forces. 3. Each command should circulate available copies among its officers. Reproduction within the military service is permitted provided (1) the source is stated, (2) the classification is not changed, and (3) the information is safeguarded. Attention is invited to paragraph 10a, AR 380-5, which is quoted in part as follows: "A document * * * will be classified and * * * marked restricted when information contained therein is for official use only, or when its disclosure should be * * * denied the general public." 4. -

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Morphological Clues to the Relationships of Japanese and Korean

Morphological clues to the relationships of Japanese and Korean Samuel E. Martin 0. The striking similarities in structure of the Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungusic languages have led scholars to embrace the perennially premature hypothesis of a genetic relationship as the "Altaic" family, and some have extended the hypothesis to include Korean (K) and Japanese (J). Many of the structural similarities that have been noticed, however, are widespread in languages of the world and characterize any well-behaved language of the agglutinative type in which object precedes verb and all modifiers precede what is mod- ified. Proof of the relationships, if any, among these languages is sought by comparing words which may exemplify putative phono- logical correspondences that point back to earlier systems through a series of well-motivated changes through time. The recent work of John Whitman on Korean and Japanese is an excellent example of productive research in this area. The derivative morphology, the means by which the stems of many verbs and nouns were created, appears to be largely a matter of developments in the individual languages, though certain formants have been proposed as putative cognates for two or more of these languages. Because of the relative shortness of the elements involved and the difficulty of pinning down their semantic functions (if any), we do well to approach the study of comparative morphology with caution, reconstructing in depth the earliest forms of the vocabulary of each language before indulging in freewheeling comparisons outside that domain. To a lesser extent, that is true also of the grammatical morphology, the affixes or particles that mark words as participants in the phrases, sentences (either overt clauses or obviously underlying proposi- tions), discourse blocks, and situational frames of reference that constitute the creative units of language use. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE STORY BEHIND THE STORIES British and Dominion War Correspondents in the Western Theatres of the Second World War Brian P. D. Hannon Ph.D. Dissertation The University of Edinburgh School of History, Classics and Archaeology March 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 6 The Media Environment ……………...……………….……………………….. 28 What Made a Correspondent? ……………...……………………………..……. 42 Supporting the Correspondent …………………………………….………........ 83 The Correspondent and Censorship …………………………………….…….. 121 Correspondent Techniques and Tools ………………………..………….......... 172 Correspondent Travel, Peril and Plunder ………………………………..……. 202 The Correspondents’ Stories ……………………………….………………..... 241 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 273 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………...... 281 Appendix …………………………………………...………………………… 300 3 ABSTRACT British and Dominion armed forces operations during the Second World War were followed closely by a journalistic army of correspondents employed by various media outlets including news agencies, newspapers and, for the first time on a large scale in a war, radio broadcasters. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

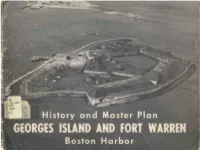

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

The Languages of Japan and Korea. London: Routledge 2 The

To appear in: Tranter, David N (ed.) The Languages of Japan and Korea. London: Routledge 2 The relationship between Japanese and Korean John Whitman 1. Introduction This chapter reviews the current state of Japanese-Ryukyuan and Korean internal reconstruction and applies the results of this research to the historical comparison of both families. Reconstruction within the families shows proto-Japanese-Ryukyuan (pJR) and proto-Korean (pK) to have had very similar phonological inventories, with no laryngeal contrast among consonants and a system of six or seven vowels. The main challenges for the comparativist are working through the consequences of major changes in root structure in both languages, revealed or hinted at by internal reconstruction. These include loss of coda consonants in Japanese, and processes of syncope and medial consonant lenition in Korean. The chapter then reviews a small number (50) of pJR/pK lexical comparisons in a number of lexical domains, including pronouns, numerals, and body parts. These expand on the lexical comparisons proposed by Martin (1966) and Whitman (1985), in some cases responding to the criticisms of Vovin (2010). It identifies a small set of cognates between pJR and pK, including approximately 13 items on the standard Swadesh 100 word list: „I‟, „we‟, „that‟, „one‟, „two‟, „big‟, „long‟, „bird‟, „tall/high‟, „belly‟, „moon‟, „fire‟, „white‟ (previous research identifies several more cognates on this list). The paper then concludes by introducing a set of cognate inflectional morphemes, including the root suffixes *-i „infinitive/converb‟, *-a „infinitive/irrealis‟, *-or „adnominal/nonpast‟, and *-ko „gerund.‟ In terms of numbers of speakers, Japanese-Ryukyuan and Korean are the largest language isolates in the world. -

1 Coast Artillery Living History Fort

Coast Artillery Living History Fort Hancock, NJ On 20-22 May 2016, the National Park Service (NPS) conducted the annual spring Coast Defense and Ocean Fun Day (sponsored by New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium – (http://njseagrant.org/) in conjunction with the Army Ground Forces Association (AGFA) and other historic and scientific organizations. Coast Defense Day showcases Fort Hancock’s rich military heritage thru tours and programs at various locations throughout the Sandy Hook peninsula – designated in 1982 as “The Fort Hancock and Sandy Hook Proving Ground National Historic Landmark”. AGFA concentrates its efforts at Battery Gunnison/New Peck, which from February to May 1943 was converted from a ‘disappearing’ battery to a barbette carriage gun battery. The members of AGFA who participated in the event were Doug Ciemniecki, Donna Cusano, Paul Cusano, Chris Egan, Francis Hayes, Doug Houck, Richard King, Henry and Mary Komorowski, Anne Lutkenhouse, Eric Meiselman, Tom Minton, Mike Murray, Kyle Schafer, Paul Taylor, Gary Weaver, Shawn Welch and Bill Winslow. AGFA guests included Paul Casalese, Erika Frederick, Larry Mihlon, Chris Moore, Grace Natsis, Steve Rossi and Anthony Valenti. The event had three major components: (1) the Harbor Defense Lantern Tour on Friday evening; (2) the Fort Hancock Historic Hike on Saturday afternoon and (3) Coastal Defense Day on Sunday, which focused on Battery Gunnison/New Peck operations in 1943, in conjunction with Ocean Fun Day. The educational objective was to provide interpretation of the Coast Artillery mission at Fort Hancock in the World War Two-era with a focus on the activation of two 6” rapid fire M1900 guns at New Battery Peck (formerly Battery Gunnison). -

REFERENCE BOOK Table of Contents Designer’S Notes

REFERENCE BOOK Table of Contents Designer’s Notes ............................................................ 2 31.0 Mapmaker’s Notes ................................................. 40 26.0 Footnoted Entries ........................................... 2 32.0 Order of Battle ....................................................... 41 27.0 Game Elements .............................................. 13 33.0 Selected Sources & Recommended Reading ......... 48 28.0 Units & Weapons ........................................... 21 29.0 OB Notes ....................................................... 33 30.0 Historical Notes ............................................. 39 GMT Games, LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 2 Operation Dauntless Reference Book countryside characterized by small fields rimmed with thick and Designer’s Notes steeply embanked hedges and sunken roads, containing small stout I would like to acknowledge the contributions of lead researchers farms with neighbouring woods and orchards in a broken landscape. Vincent Lefavrais, A. Verspeeten, and David Hughes to the notes Studded with small villages, ideal for defensive strongpoints…” appearing in this booklet, portions of which have been lifted rather 6 Close Terrain. There are few gameplay differences between close liberally from their emails and edited by myself. These guys have terrain types. Apart from victory objectives, which are typically my gratitude for a job well done. I’m very pleased that they stuck village or woods hexes, the only differences are a +1 DRM to Re- with me to the end of this eight-year project. covery rolls in village hexes, a Modifier Chit which favors village and woods over heavy bocage, and a higher MP cost to enter woods. Furthermore, woods is the only terrain type that blocks LOS with 26.0 Footnoted Entries respect to spotting units at higher elevation. For all other purposes, close terrain is close terrain. -

Thyroid Cancer in Children and Adolescents of Bryansk and Kaluga Regions

BY0000285 Thyroid Cancer in Children and Adolescents of Bryansk and Kaluga Regions A.F. TSYB, E.M. PARSHKOV, V.V. SHAKHTARIN, V.F. STEPANENKO, V.F. SKVORTSOV, I.V. CHEBOTAREVA MRRC RAMS, Obninsk, Russia Abstract We analyzed 62 cases of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents of Bryansk and Kaluga regions, the most contaminated as a result of the Chernobyl accident. The data on specified radiation situation as well as probable radiation doses to the thyroid are given. It is noted that the development of thyroid cancer depends on the age of children at the time of accident (0-3, 7-9, 12-15 years). They arc the most critical periods for the formation and functioning of the thyroid, in particular, in girls. It is suggested that thyroid cancer develops in children and teenagers residing in areas with higher Cs-137 contamination level at younger age than in those residing in less contaminated regions. It is shown that the minimal latent period in the development of thyroid cancer makes up to 5 years. The results of ESR method on tooth enamel specimen indicate that over postaccident period the sufficient share of children has collected such individual radiation dose which are able to affect on their health stale and development of thyroid pathology. For a long period of time Russia unlike Belarus and Ukraine was considered to be "favourable" by the development of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents after the Chernobyl accident. Such a fact appeared to be a dissonance in the common concept on the possible radiation induction of thyroid tissues to malignancy when received relatively low doses of iodine radionuclide. -

Provided Below Is Information for the Transportation of Firearms and Ammunition for Airline Travel

Provided below is information for the transportation of firearms and ammunition for airline travel. AS STATED IN JULY 2008 Most airlines have provided a link to the specific web pages for Baggage Allowances, Carry-on Baggage information, Firearms and Ammunition, Restricted Articles and Specialty Items of which can include but is not limited to antlers, game meats and fishing equipment. The TSA website is truly the end all be all for airline travel regulations. Canadian and European transportation agencies have essentially the same regulations and generally defer some of their information to the TSA. Before starting any research for your flight it is imperative that you thoroughly look at the TSA website because they have the broadest amount of information and they are the supreme authority. When traveling internationally, here are three issues by most if not all of the airline carriers: 1) The airlines have stated that their policy for transporting firearms is the same for both domestic and international flights. 2) They advise that you call the airline desk at your departure airport to inform them that you are flying with a firearm and to get the most up-to-date information on procedures at that airport. 3) If you are transferring from one airline to another, it is imperative for you to call the second airline to check if they have any additional regulations, especially if your transfer is in an international airport. There may be additional permits or procedures to be processed prior to your arrival. 4) Certain temporary visitor permits are required if you are planning on staying overnight in an international location that is not your final destination. -

Šablona -- Diplomová Práce (Fmk)

Sada obalů Lucie Leinweberová Bakalářská práce 2019 ***nascannované zadání s. 2*** ABSTRAKT Práce se zaměřuje na kolekci minimalistických kabelek z odpadního materiálu EVA. Spojení materiálu zámkovým systémem vytváří zajímavý detail na hraně kabelky. Teoretická část se zabývá historii kabelky a dělí kabelky na kategorie. Praktická část popi- suje samotný průběh navrhování a technické řešení spojení. Projektová část se zabývá cestou k výrobku samotnému. Klíčová slova: Kabelka, taška, EVA, recyklace, obal, produkt, módní doplněk ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on a collection of minimalistic handbags from EVA waste material. Com- bining the material with the locking system creates an interesting detail on the handbag edge. The theoretical part deals with handbag history and divides handbags into categories. The practical part describes the design process itself and the technical solution of the connection. The project part deals with the way to the product itself. Keywords: Handbag, bag, EVA, recycling, packaging, product, fashion accessory Děkuji panu MgA. Ivanu Pecháčkovi za lidský přístup, cenné rady, připomínky a odborné vedení které mi poskytoval nejen během práce na tomto zadání, ale i po dobu celého studia. Děkuji za možnost se zlepšovat vedle svých přátel a spo- lužáků. Prohlašuji, že odevzdaná verze bakalářské/diplomové práce a verze elektronická nahraná do IS/STAG jsou totožné. OBSAH ÚVOD .................................................................................................................................... 9 I TEORETICKÁ