Arbeitsfassung 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: Elements of Classical Oratory in His Drammi Per Musica

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: elements of Classical Oratory in his drammi per musica A thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Heath A. W. Landers, BMus (Hons) School of Creative Arts The University of Newcastle May 2015 The thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Candidate signature: Date: 06/05/2015 In Memory of My Father, Wayne Clive Landers (1944-2013) Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat ei. Acknowledgments Foremost, my sincerest thanks go to Associate Professor Rosalind Halton of the University Of Newcastle Conservatorium Of Music for her support and encouragement of my postgraduate studies over the past four years. I especially thank her for her support of my research, for her advice, for answering my numerous questions and resolving problems that I encountered along the way. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor Conjoint Professor Michael Ewans of the University of Newcastle for his input into the development of this thesis and his abundant knowledge of the subject matter. My most sincere and grateful thanks go to Matthew Hopcroft for his tireless work in preparing the musical examples and finalising the layout of this dissertation. -

Das Tragico Fine Auf Venezianischen Opernbühnen Des Späten 18

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Heidelberger Dokumentenserver Das tragico fine auf venezianischen Opernbühnen des späten 18. Jahrhunderts Textband Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Zentrum für Europäische Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar vorgelegt bei Prof. Dr. Silke Leopold von Katharina Kost November 2004 INHALT DANKSAGUNG............................................................................................. IV TEIL I: DIE FRAGE EINLEITUNG .................................................................................................................... 2 Die Geschichte des tragico fine in der italienischen Oper des 18. Jahrhunderts – Forschungsüberblick ........................................................................................................ 2 Tragico fine zwischen 1695 und 1780 ......................................................................... 4 Bislang in der Forschung berücksichtigte Aspekte im Repertoire ab 1780 .................. 9 Fragestellung und Vorgehensweise ................................................................................ 15 Die Eingrenzung des Repertoires .............................................................................. 15 Das Repertoire im Überblick ..................................................................................... 18 Untersuchung anhand von Vergleichen – Dramaturgie -

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE to MODERATORS: in Answers, Information in Parentheses Is Optional Extra Information

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE TO MODERATORS: in answers, information in parentheses is optional extra information. A slash ( / ) indicates an alternate answer. Underlined portions of a longer, narrative answer indicate required information. ROUND ONE 1. TOSSUP: From what Latin noun, with what meaning, do the words ignition and igneous ultimately derive? ANS: IGNIS, FIRE BONUS: From what Latin verb, with what meaning, do the words coherent and adhesion derive? ANS: HAEREŌ, STICK/CLING 2. TOSSUP: According to Livy and Plutarch, what legendary Roman triumphed four times, was dictator five times, was never once consul, was honored with the title “Second Founder of Rome,” and conquered the city of Veii in 396 BC? ANS: (M. FURIUS) CAMILLUS BONUS: Following the victory over Veii, for what accusation did his political adversaries impeach Camillus? ANS: EMBEZZLEMENT 3. TOSSUP: According to Hesiod, what moon titan, the daughter of Ouranos and Gaia, bore Leto from the union with her brother Coeus? ANS: PHOEBE BONUS: According to Hesiod, what Star goddess was also the daughter of Phoebe and Coeus and the mother of Hecate? ANS: Asteria 4. TOSSUP: What fifteen-book work of Ovid ends with the apotheosis of Julius Caesar? ANS: METAMORPHOSES BONUS: What other work of Ovid, consisting of epistolary poems written by mythological heroines, allowed him to claim that he had created a new genre of mythological elegy? ANS: HEROIDES rd 5. TOSSUP: Give the 3 person singular, pluperfect active subjunctive of noceō, nocēre. ANS: NOCUISSET nd BONUS: Now give the 2 person plural present subjunctive of morior, morī. -

Raffaele Pe, Countertenor La Lira Di Orfeo

p h o t o © N i c o l a D a l M Raffaele Pe, countertenor a s o ( R Raffaella Lupinacci, mezzo-soprano [track 6] i b a l t a L u c e La Lira di Orfeo S t u d i o Luca Giardini, concertmaster ) ba Recorded in Lodi (Teatro alle Vigne), Italy, in November 2017 Engineered by Paolo Guerini Produced by Diego Cantalupi Music editor: Valentina Anzani Executive producer & editorial director: Carlos Céster Editorial assistance: Mark Wiggins, María Díaz Cover photos of Raffaele Pe: © Nicola Dal Maso (RibaltaLuce Studio) Design: Rosa Tendero © 2018 note 1 music gmbh Warm thanks to Paolo Monacchi (Allegorica) for his invaluable contribution to this project. giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero 5 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (c165 3- 1723) Sdegnoso turbine 3:02 Opera arias (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , Rome, 1713, I.2; libretto by Antonio Ottoboni) role: Giulio Cesare ba 6 George Frideric Handel Son nata a lagrimar 7:59 (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.12; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) roles: Sesto and Cornelia 1 George Frideric Handel (168 5- 1759) Va tacito e nascosto 6:34 7 Niccolò Piccinni (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.9; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) Tergi le belle lagrime 6:36 role: Giulio Cesare (sung in London by Francesco Bernardi, also known as Senesino ) (from Cesare in Egitto , Milan, 1770, I.1; libretto after Giacomo Francesco Bussani) role: Giulio Cesare (sung in Milan by Giuseppe Aprile, also known as Sciroletto ) 2 Francesco Bianchi (175 2- -

Rethinking Ovid: a Collection of Latin Poetry and Commentary on Composition Anna C

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department May 2006 Rethinking Ovid: A Collection of Latin Poetry and Commentary on Composition Anna C. Everett Macalester College, [email protected] Anna Everett Beek Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Recommended Citation Everett, Anna C. and Beek, Anna Everett, "Rethinking Ovid: A Collection of Latin Poetry and Commentary on Composition" (2006). Classics Honors Projects. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/1 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RethinkingRethinking Ovid: A Collection of Latin Poetry and Commentary on Composition Anna Everett Beek Advised by Nanette Scott Goldman Department of Classics, Macalester College 1 May 2006 Cunct rum Chrone impl cbilissime d vum, scr bend vers s t bi ni hil referunt. TableTable of Contents Introduction 4 Sources and Inspiration Cydippe 7 Dryope 10 Other References 11 Composition 12 The Chosen Meters 17 Poetic Devices 19 Diction and Grammar in Chronologica l Context: Linguistic Matters 22 Imitat io n and Interpretation 26 Historical Background: Ceos 29 Historical Background: Women 31 Conclusion 34 The Poetry Cydippe 35 Dryope 39 Bibliography 41 2 AcknowledgementsAcknowledgements I could not have completed this project without the help of various wonder ful people. While I am certain they know who they are, I must extend much gratitude to these people, and if I have produced any work of quality, these people deserve credit first. -

2017 Mar-Apr

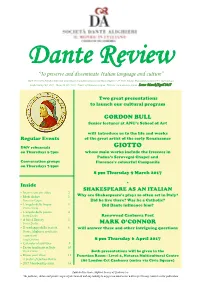

Dante Review “To preserve and disseminate Italian language and culture” ISSN 1441-8592 Periodico bimestrale del Comitato di Canberra della Società Dante Alighieri - 2nd Floor Notaras Multicultural Centre 180 London Circuit Canberra City ACT 2601 - Phone: 02 6247 1884 - Email: [email protected] - Website: www.danteact.org.au - Issue: March/April 2017 Two great presentations to launch our cultural program GORDON BULL Senior lecturer at ANU’s School of Art will introduce us to the life and works Regular Events of the great artist of the early Renaissance DMV rehearsals GIOTTO on Thursdays 5-7pm whose main works include the frescoes in Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel and Conversation groups Florence’s colourful Campanile on Thursdays 7-9pm 8 pm Thursday 9 March 2017 * Inside SHAKESPEARE AS AN ITALIAN News from the office 2 Why are Shakespeare’s plays so often set in Italy? Modi di dire 3 Francesca Foppoli Did he live there? Was he a Catholic? L’angolo della lingua 3 Did Dante influence him? Yvette Devlin L’angolo della poesia 4 Yvette Devlin Renowned Canberra Poet A bit of History 5 Yvette Devlin MARK O’CONNOR Il sondaggio della Società 6 will answer these and other intriguing questions Dante Alighieri: risultati e commenti Luigi Catizone 8 pm Thursday 6 April 2017 Calendar of activities 9 Easter traditions in Italy 10 Yvette Devlin Both presentations will be given in the Know your choir 12 Function Room - Level 2, Notaras Multicultural Centre A profile of Ondina Matera 180 London Cct Canberra (entry via Civic Square) 2017 Membership form 16 Published by Dante Alighieri Society of Canberra Inc. -

Gaio Giulio Cesare Progetto AUREUS-Classe VF Prof.Ssa Marisa Panetta A.S

Gaio Giulio Cesare Progetto AUREUS-classe VF prof.ssa Marisa Panetta a.s. 2018-2019 Gaio Giulio Cesare nella storiografia LA VITA Dal 100 A.C. al 60 A.C. Cesare nacque il 13 o il 12 luglio del 100 a.C. in un quartiere romano chiamato “Suburra” da una nota famiglia , la “Gens Iulia”. A 16 anni ripudiò la promessa sposa Cossuzia per sposare Cornelia minore che era la figlia di Lucio Cornelio Cinna. Durante la dittatura di Silla a Cesare fu intimato di divorziare da Cornelia poiché non era di origine patrizia, ma egli rifiutò. Allora Silla, poiché non aveva obbedito a un suo ordine, voleva ucciderlo, ma dovette desistere per i numerosi appelli rivoltigli dalle Vestali che prevedevano un futuro glorioso per Cesare. Cesare per la paura scappò in Sabina e, arrivato alla giusta età, divenne legato del pretore Minucio Termo in Asia. Finito questo periodo di servizio militare, rimase in Cilicia come patrizio romano sotto il comando di Servilio Isaurico. Quando Silla si dimise dalla carica di dittatore nell’80, Cesare tornò a Roma nel 78 ovvero dopo la morte di Silla, allora iniziò come esponente del partito dei populares e nemico degli optimates la sua carriera nella quale mostrò una grandissima intelligenza politica. Busto di Cesare in uniforme militare. Cesare fu eletto questore nel 69, un periodo in cui il clima politico romano stava cambiando grazie alla fine della dittatura sillana. Durante quest’anno, Cesare si recò in Spagna Ulteriore governata dal propretore Vetere, nella quale si dedicò all’attività giudiziaria . Nel 65 fu eletto edile curule e, inoltre, divenne leader del movimento popolare, mentre nel 63 divenne pontefice massimo dopo la morte di quinto Cecilio Metello Pio. -

Pierrot Lunaire

Words and Music Liverpool Music Symposium 3 Words and Music edited by John Williamson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2005 by LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS 4 Cambridge Street, Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © Liverpool University Press 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 0-85323-619-4 cased Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and the publishers will be pleased to be informed of any errors or omissions for correction in future editions. Edited and typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Notes on Contributors vii Introduction John Williamson 1 1 Mimesis, Gesture, and Parody in Musical Word-Setting Derek B. Scott 10 2 Rhetoric and Music: The Influence of a Linguistic Art Jasmin Cameron 28 3 Eminem: Difficult Dialogics David Clarke 73 4 Artistry, Expediency or Irrelevance? English Choral Translators and their Work Judith Blezzard 103 5 Pyramids, Symbols, and Butterflies: ‘Nacht’ from Pierrot Lunaire John Williamson 125 6 Music and Text in Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw Bhesham Sharma 150 7 Rethinking the Relationship Between Words and Music for the Twentieth Century: The Strange Case of Erik Satie Robert Orledge 161 vi 8 ‘Breaking up is hard to do’: Issues of Coherence and Fragmentation in post-1950 Vocal Music James Wishart 190 9 Writing for Your Supper – Creative Work and the Contexts of Popular Songwriting Mike Jones 219 Index 251 Notes on Contributors Derek Scott is Professor of Music at the University of Salford. -

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1 The following characters are described in the pages that follow the list. Page Order Alphabetical Order Aeolus 2 Achaemenides 8 Neptune 2 Achates 2 Achates 2 Aeolus 2 Ilioneus 2 Allecto 19 Cupid 2 Amata 17 Iopas 2 Andromache 8 Laocoon 2 Anna 9 Sinon 3 Arruns 22 Coroebus 3 Caieta 13 Priam 4 Camilla 22 Creusa 6 Celaeno 7 Helen 6 Coroebus 3 Celaeno 7 Creusa 6 Harpies 7 Cupid 2 Polydorus 7 Dēiphobus 11 Achaemenides 8 Drances 30 Andromache 8 Euryalus 27 Helenus 8 Evander 24 Anna 9 Harpies 7 Iarbas 10 Helen 6 Palinurus 10 Helenus 8 Dēiphobus 11 Iarbas 10 Marcellus 12 Ilioneus 2 Caieta 13 Iopas 2 Latinus 13 Juturna 31 Lavinia 15 Laocoon 2 Lavinium 15 Latinus 13 Amata 17 Lausus 20 Allecto 19 Lavinia 15 Mezentius 20 Lavinium 15 Lausus 20 Marcellus 12 Camilla 22 Mezentius 20 Arruns 22 Neptune 2 Evander 24 Nisus 27 Nisus 27 Palinurus 10 Euryalus 27 Polydorus 7 Drances 30 Priam 4 Juturna 31 Sinon 2 An outline of the ACL presentation is at the end of the handout. Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 2 Aeolus – with Juno as minor god, less than Juno (tributary powers), cliens- patronus relationship; Juno as bargainer and what she offers. Both of them as rulers, in contrast with Neptune, Dido, Aeneas, Latinus, Evander, Mezentius, Turnus, Metabus, Ascanius, Acestes. Neptune – contrast as ruler with Aeolus; especially aposiopesis. Note following sympathy and importance of rhetoric and gravitas to control the people. Is the vir Aeneas (bringing civilization), Augustus (bringing order out of civil war), or Cato (actually -

Svetonio: Vita Dei Cesari

Svetonio: Vita dei Cesari LIBRO PRIMO CESARE 1 Aveva quindici anni quando perse il padre; nell'anno successivo gli fu conferita la carica di Flamendiale. Separatosi da Cossuzia, donna di famiglia equestre, ma molto ricca, alla quale era stato fidanzato fin dalla più giovane età, sposò Cornelia, figlia di Cinna, quello stesso che era stato eletto console per quattro volte. Da lei ebbe una figlia, Giulia, e neppure Silla poté costringerlo a divorziare; allora il dittatore lo privò della sua carica sacerdotale, della dote della moglie e dell'eredità familiare, inserendolo quindi nella lista dei suoi avversari. Cesare fu costretto così a starsene nascosto, a cambiare rifugio quasi ogni notte, quantunque ammalato piuttosto gravemente di febbre quartana. Finalmente, per intercessione sia delle Vergini Vestali, sia di alcuni suoi parenti, ottenne la grazia. Si dice che Silla, rifiutatosi a lungo di accogliere le preghiere dei suoi più illustri amici e oppostosi tenacemente alle insistenti richieste, alla fine, vinto, abbia esclamato, non si sa bene se per intuizione o per uno strano presentimento: «Esultate e tenetevelo stretto, ma sappiate che colui che volete salvo ad ogni costo un giorno sarà la rovina del partito aristocratico che voi avete difeso insieme con me. In Cesare, infatti, sono nascosti molti Mari.» 2 Fece il servizio di leva in Asia, presso lo stato maggiore di Marco Termo. Mandato da costui in Bitinia per cercare una flotta, si attardò presso Nicomede e qui corse voce che si fosse prostituito a quel re. Egli stesso alimentò questa diceria quando, pochi giorni più tardi, ritornò in Bitinia con la scusa di ricuperare un credito concesso ad uno schiavo affrancato, divenuto suo cliente. -

Reading the Aeneid with Intermediate Latin Students: the New Focus Commentaries (Books 1-4 and 6) and Cambridge Reading Virgil (Books I and II)

Teaching Classical Languages Fall 2012 Syson 52 Reading the Aeneid with intermediate Latin students: the new Focus commentaries (Books 1-4 and 6) and Cambridge Reading Virgil (Books I and II) Antonia Syson Purdue University ABSTRACT This review article examines the five Focus Aeneid commentaries available at the time of writing. When choosing post-beginner level teaching commentaries, my central goal is to assess whether editions help teachers and students integrate the development of broader skills in critical enquiry into their explanations of grammar, vocabulary, and style, instead of artificially separating “liter- ary” and “historical” analytic strategies from “language” skills. After briefly explaining why the well-known Vergil editions by Pharr (revised by Boyd) and Williams do not suit these priorities, I summarize the strengths of the contributions to the new Focus series by Ganiban, Perkell, O’Hara, and Johnston, with particular emphasis on O’Hara’s edition of Book 4, and compare the series with Jones’ new textbook Reading Virgil: Aeneid I and II. KEY WORDS Aeneid, AP Latin, graduate survey, Latin poetry, pedagogy, Vergil, Latin commentary, intermediate Latin. TEXTS REVIEWED Ganiban, Randall T., ed. Vergil Aeneid 1. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Com- pany, 2009. ISBN: 978-1-58510-225-9 ———. Vergil Aeneid 2. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company, 2008. ISBN: 978-1-58510-226-6 Perkell, Christine, ed. Vergil Aeneid 3. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company, 2010. ISBN: 978-1-58510-227-3 O’Hara, James, ed. Vergil Aeneid 4. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company, 2011. ISBN: 978-1-58510-228-0 Johnston, Patricia A., ed. -

Agmine Facto: Rampant Rhetoric in Aeneid I

Agmine facto: rampant rhetoric in Aeneid I RWShaw Foreign Languages, University of New Orleans, Lakefront Campus New Orleans, Louisiana 70148. 011-1-504-280-6929 (Office), 011-1-985-646-2526 (Home) E-mail: [email protected] This article is the product of continued research in Vergil's pictorial imagery, a topic addressed earlier in a paper on the Laocoon episode of the Aeneid, which appeared in the 2001 edition of SAlAH. The poet's visual rhetoric seems to remove the barriers traditionally imposed on poetry and the literary arts, and his verbal palette contains all the descriptive elements indigenous to painting, cinema, and sculpture. The convoluted verse results in the strategic placement of words to convey visually the images in his narrative format. These observations remain the premise on which I have based my commentary on the first major event of the epic, the storm sequence of Bk i. A catalogue raisonne provides a survey of the art inspired by the passage dating from early Italian Renaissance through the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. There ensues a transposition of the exegesis to the author's visual interpretation in an attempt to mirror Vergil's painter-like and sculptural qualities in the genre of abstract expressionism and to evoke once again Horace's humanistic doctrine on poetry and the visual arts, ut pictura poesis. Episodic narrative and the simile Whereas this first simile of the epic functions in a symbolic capacity to involve In her article entitled "Vergil: painter with men and elemental forces, it also works in 1 words," Pauline Turnbull stated that Vergil's collaboration with a second simile to frame painter-like quality was manifested in the the episode thematically and structurally as a descriptions of the actual and the metaphor.