THE MARYKNOLL SOCIETY and the FUTURE a PROPOSAL William B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Tribute to Maryknoll Missionary Bishop William J

1 TRIBUTE TO MARYKNOLL MISSIONARY BISHOP WILLIAM J. McNAUGHTON, MM Most Reverend John O. Barres Bishop of the Diocese of Rockville Centre February 8, 2020 The beautiful picture of Maryknoll Bishop William J. McNaughton, MM, Emeritus Bishop of Inchon, Korea and the Maryknoll Mission Archives obituary and synthesis of his global missionary spirit below express so powerfully the charisms of this great Churchman who died on February 3, 2020. I look forward to concelebrating his funeral Mass with Cardinal Sean O’Malley and Bishop McNaughton’s Maryknoll brother priests on Tuesday, February 11, 2020 at 11:00am at Our Lady of Good Counsel—St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Methuen, MA. Bishop McNaughton’s friendship with my convert Protestant minister parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, and our entire family has had a profound impact on our destinies. My parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, met each other at the Yale Divinity School after World War II and both were ordained Congregational Protestant ministers and served at a rural parish in East Windsor, Connecticut outside of Hartford. They had an excellent theological education at Yale Divinity School with such Protestant scholars as Richard and Reinhold Niehbuhr, Paul Tillich and the Martin Luther expert Church historian Roland Bainton. In his book One Shepherd, One Flock (published by Sheed and Ward in 1955 and republished by Catholic Answers in 2000), my father Oliver describes the spiritual and intellectual journey he and my mother Marjorie experienced 2 after their marriage and ordination as Congregational ministers which led to their conversion to the Catholic Church in 1955. -

Holy Cross Parish

HOLY CROSS PARISH ONE PARISH ╬ TWO CHURCHES Blessed Sacrament Church, 3012 Jackson Street, Sioux City, Iowa 51104 St. Michael Church, 2223 Indian Hills Drive, Sioux City, Iowa 51104 August 4, 2019 DAILY MASS SCHEDULE Monday -Friday: 6:45 am at Blessed Sacrament Monday -Thursday: 5:30 pm at St. Michael WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE Saturday: 4:30 pm at St. Michael Sunday: 8:00 am at Blessed Sacrament 9:00 am at St. Michael 18th Sunday in Ordinary Time 10:00 am at Blessed Sacrament 11:00 am at Lectio Divina—Luke 12:13 -21 St. Michael ** “ Consumerism creates needs Read and awakens in us the desire of Reflect RADIO MASS gaining. Every Sunday at Respond 9:00 A.M. on What do you do so as not to be a Rest KSCJ 1360 AM victim of gain brought about by or 94.9 FM consumerism? ” **ocarm.org/en/content/lectio/lectio -divina -luke -1213 -21 From the desk of the Pastor— Fr. David Hemann August 4—18 th Sunday in DO YOU KNOW THE MEANING OF Ordinary Time THE VIRGINAL CONCEPTION What is the one thing you OF JESUS? have that sudden disaster can not take away? Answer: The virginal conception of Jesus means that YOUR IMMORTAL Jesus was conceived in the womb of the Vir- SOUL! It would stand to gin Mary only by the power of the Holy Spir- reason then, that care of it without the intervention of a man. Jesus is your soul should be the the Son of the heavenly Father according to his FIRST priority of your life divine nature and the Son of Mary according to his and along with that, the care human nature. -

Maryknoll Alumnae News

Maryknoll Alumnae News Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital (OLMH), Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong In 1957, in response to the thousands of refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong from mainland China, Maryknoll Sisters obtained permission from the Hong Kong Government and received a land grant in Wong Tai Sin to build a hospital to serve the poor. With the help of the Far East Refugee Program of the American Foreign Service, Hong Kong Land Grant and Catholic Relief Services, OLMH was officially opened on August 16, 1961. (Photos courtesy of Sr. Betty Ann Maheu from her book, Maryknoll Sisters, Hong Kong, Macau, China, 1968-2007) Many programs were initiated in the 1970s: Volunteer Program, Community Nursing Service, School of Nursing, Training Seminarians for Hospital Ministry, and Hospital Pastoral Ministry. Later on, Palliative Care clinic was opened to care for people suffering from cancer, the number one cause of death in Hong Kong. In 1982, the first Hospice Care was started in Hong Kong, like Palliative Care Unit, it was the “first” of these special medical services for the people in Hong Kong. In order to continue to serve the lower income brackets of society, OLMH opted to become one of the 33 public hospitals under the Hospital Authority in October 30, 1987. Fast forward to today: OLMH has undergone many operating and administration changes and has continued to offer more services in the community with new procedures. Magdalen Yum, MSS 1976, recently visited OLMH for a private tour. Following is her latest update and photos of the new wing and latest equipment. -

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers Founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the First American-Based Catholic Foreign Missions Society for Women

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the first American-based Catholic foreign missions society for women. Mary Josephine Rogers, called “Mollie” by her family, was born Oct. 27, 1882, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. After graduating from Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, she earned her teaching certificate. Mary taught for several years at Smith College, followed by teaching assignments in several public elementary and high schools in the Boston area. Interest in Foreign Missions Mary was deeply impacted by the flourishing Protestant Student Volunteer Movement that was sending missionaries around the world. In 1908, due to her growing interest in missionary work, she began volunteering her time to assist Father James Walsh in writing and editing the Catholic Foreign Missionary Society of America’s magazine Field Afar, now known as Maryknoll. In September 1910 at the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal, Canada, Mary realized she shared a passion to develop a foreign missions society based in the United States with Father Walsh and Father Thomas Frederick Price. As a result of this common vision, they founded the Maryknoll Mission Movement. Mary provided assistance to the group from Boston where she had family responsibilities before finally joining them in September 1912. She was given the formal name, “Mary Joseph.” She founded a lay group of women interested in missions known as the Teresians, named after the 16th Century Spanish Catholic nun St. Teresa of Avila. In 1913, both the male and female societies moved to Ossining, New York to a farm renamed “Maryknoll.” The pope recognized the work of the Teresians in 1920, allowing the growing society to be designated as a diocesan religious congregation, officially the Foreign Mission Sisters of St. -

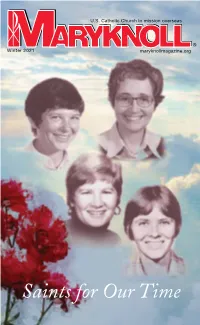

Saints for Our Time from the EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS

U.S. Catholic Church in mission overseas ® Winter 2021 maryknollmagazine.org Saints for Our Time FROM THE EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS n the centerspread of this issue of Maryknoll we quote Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship, which Despite Restrictions of 2 From the Editor Iwas released shortly before we wrapped up this edition and sent it to the COVID-19, a New Priest Is 10 printer. The encyclical is an important document that focuses on the central Ordained at Maryknoll Photo Meditation by David R. Aquije 4 theme of this pontiff’s papacy: We are all brothers and sisters of the human family living on our common home, our beleaguered planet Earth. Displaced by War 8 Missioner Tales The joint leadership of the Maryknoll family, which includes priests, in South Sudan 18 brothers, sisters and lay people, issued a statement of resounding support by Michael Bassano, M.M. 16 Spirituality and agreement with the pope’s message, calling it a historic document on ‘Our People Have Already peace and dialogue that offers a vision for global healing from deep social 40 In Memoriam and economic divisions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We embrace Canonized Them’ by Rhina Guidos 24 the pope’s call,” the statement says, “for all people of good will to commit to 48 Orbis Books the sense of belonging to a single human family and the dream of working together for justice and peace—a call that includes embracing diversity, A Listener and Healer 56 World Watch encounter, and dialogue, and rejecting war, nuclear weapons, and the death by Rick Dixon, MKLM 30 penalty.” 58 Partners in Mission This magazine issue is already filled with articles that clearly reflect the Finding Christmas very interconnected commonality that Pope Francis preaches, but please by Martin Shea, M.M. -

The Catholic Church in China: a New Chapter

The Catholic Church in China: A New Chapter PETER FLEMING SJ with ISMAEL ZULOAGA SJ Throughout the turbulent history of Christianity in China, Christians have never numbered more than one per cent of China's total population, but Christianity has never died in China as many predicted it eventually would. One could argue that Christianity's influence in China has been greater than the proportion of its Christians might warrant. Some have argued that Christianity became strong when Chinese governments were weak: What we seem to be witnessing today in China, however, is a renewal of Christianity under a vital communist regime. That Christianity is in some ways becoming stronger today under a communist regime than it was before the communists is an irony of history which highlights both the promise and the burden of Christianity's presence in China. Today China is no less important in the history of Christianity than she was during Francis Xavier's or Matteo Ricci's time. There are one billion Chinese in China today and 25 million overseas Chinese. These numbers alone tell us of China's influence on and beneficial role for the future and the part that a culturally indigenous Chinese Christianity might play in that future. There is a new look about China today. What does Christianity look like? What has it looked like in the past? The promise and burden of history The Nestorians first brought Christianity to China in the seventh century. The Franciscans John of PIano Carpini and John of Montecorvino followed them in the 13th century. -

Ontario Maryknollers

April 2011 Spring Edition Ontario Maryknollers Official Newsletter of Maryknoll Convent Former Students (Ont.) Committee Members 2010~2012 Important Announcement The next WWR will be in Toronto. President Jacqueline Lam Fong Please read the letter from Sr. Jeanne. Vice-Presidents Linda da Rocha Little Nena Prata Noronha Treasurers Lily Wong Yeung Patricia Ho Wu Secretaries Irene Legay Dear Maryknollers, Wendy Man th During our 7 WWR celebration dinner on February 21, 2010, Maryknollers Newsletter Production voted to have the next reunion in Vancouver. Unfortunately, they are not able Gertrude Chan to do this and asked the Toronto Chapter to take it. Toronto graciously re- plied “yes”. To make the celebration more meaningful, the Toronto girls Activities th Marie Louise Rocha Chang asked to co-celebrate their Chapter‟s 30 Anniversary and the WWR in 2014. Marilyn Hall Pun I support this decision and know that you too will understand that circum- stances have changed our original plans. Membership/Directory Ludia Au Fong Sr. Jeanne Houlihan Web-site Administrator Gertrude Chan Mailing Address: P.O. Box 20056 Nymark Postal Outlet 4839 Leslie Street North York, ON. M2J 5E4 Web Site: http:// www.mcsontario.org E-mail Address for 8th Worldwide Reunion mcswwr2014 @gmail.com April 2011 Spring Edition, p.2 January 14, 2011 Dear Jacqueline and New Committee Members, I am writing this to congratulate you for being elected to the Members Committee for 2010 to 2012. We thank you for accepting such important positions to give a bonding force to all the Maryknollers Ontario, to continue the Maryknoll family spirit, caring for one another; to carry out the legacy of the Maryknoll spirit handed down to you by Mother Mary Joseph, our Foundress, through the Maryknoll Sisters, and to lavish boundless love on the Maryknoll Sisters. -

Missiological Reflections on the Maryknoll Centenary

Missiological Reflections on the Maryknoll Centenary: Maryknoll Missiologists’ Colloquium, June 2011 This year Maryknoll celebrates its founding as the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America. In the early 1900s, the idea of founding a mission seminary in the United States circulated among the members of the Catholic Missionary Union. Archbishop John Farley of New York had suggested the establishment of such a seminary, and also tried to entice the Paris Foreign Mission Society to open an American branch. Finally, two diocesan priests, Fathers James Anthony Walsh and Thomas Frederick Price, having gained a mandate to create a mission seminary from the archbishops of the United States, travelled to Rome and received Pope Pius X’s permission to do so. The date was June 29, 1911, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. In the years since, well over a thousand Maryknoll priests and Brothers have gone on mission to dozens of countries throughout the world. Many died young in difficult missions, and not a few have shed their blood for Christ. This is a time to celebrate the glory given by Christ to His relatively young Society. The main purpose of this event, though, is not to glory in our past. We celebrate principally to fulfill the burning desire of our founders, in words enshrined over the main entrance of the Seminary building, Euntes Docete Omnes Gentes, “Go and teach all nations” (Matthew 28:19). Nearly twenty centuries after Christ gave this command, the Church, during the Second Vatican Council, again defined this as the fundamental purpose of mission, being “sent out by the Church and going forth into the whole world, to carry out the task of preaching the Gospel and planting the Church among peoples or groups who do not yet believe in Christ” (Ad Gentes, 6). -

St. Luke the Evangelist Church

ST. LUKE THE EVANGELIST CHURCH EASTON ROAD & FAIRHILL AVENUE GLENSIDE, PENNSYLVANIA OCTOBER 16, 2011 MISSION STATEMENT CHURCH AND RECTORY OFFICE 2316 Fairhill Avenue We, the parish family of St. Luke the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church, Glenside, PA 19038 respecting our tradition, affirming our strong family ties, and valuing our diverse community, are called by Baptism to commit ourselves to: 215-572-0128 fax: 215-572-0482 • Give glory to God by liturgy which unites and strengthens the community [email protected] of faith; • Build a church community that welcomes all, encouraging each home to be Office Hours: a domestic church; 9:00 AM - 3:00 PM, MONDAY • Listen to the Gospel of Jesus, live it in our daily lives, and share it with 9:00 AM - 8:00 PM, TUESDAY-THURSDAY one another; and 9:00 AM - 3:00 PM, FRIDAY • Serve others as Jesus did, especially the poor and those in need. www.stlukerc.org MASS SCHEDULE Saturday Vigil: 5:00 PM Sunday: 7:30, 9:30, 11:30 AM Daily: Monday, Wednesday, Friday: 6:30 AM Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday: 8:30 AM Holy Day: varies; Holiday: varies SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION Wednesday: 7:30 - 8:00 PM Saturday: 4:00 - 4:30 PM 29TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME RELIGIOUS EDUCATION OFFICE QUESTION OF THE WEEK 2330 Fairhill Avenue Glenside, PA 19038 “Then repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God.” 215-884-2080 Matthew 22:21b What are you doing to bring Caesar’s world ST. LUKE SCHOOL OFFICE 2336 Fairhill Avenue into harmony with God’s world? Glenside, PA 19038 215-884-0843 FORTY HOURS fax: 215-884-4607 www.saintlukeschool.org SUNDAY—TUESDAY 061 St. -

1. Pioneer Protestant Missionaries in Korea Seoul/1887 William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University

1. Pioneer Protestant Missionaries in Korea Seoul/1887 William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University This rare early photograph includes several of the most prominent pioneer American Presbyterian and Methodist missionary families just a year or two after their arrival in Korea. At the far left in the top row is John W. Heron, the first appointed Presbyterian medical doctor who died of dysentery in 1890, only five years after his arrival in Korea as a missionary. In the middle of the same row is Henry G. Appenzeller, the pioneer Methodist missionary educator who established the first Western-style school in Korea known as the Paejae Academy. At the far right is William B. Scranton, the pioneer Methodist medical missionary who perhaps is most remembered today for having brought his mother to Korea. In the middle row at the far left is Mrs. John “Hattie” Herron, who in 1892 became Mrs. James S. Gale following her husbandʼs untimely death. To the right are Mrs. Henry Ella Dodge Appenzeller, Mrs. William B. Scranton, and the indomitable Mrs. Mary F. Scranton, the mother of William B. Scranton, who founded the school for girls that developed into Ewha University. In the bottom row (l–r) are Annie Ellers—a Presbyterian missionary nurse who later transferred to the Methodist Mission following her marriage to Dalzell A. Bunker—Horace G. Underwood, the first ordained Presbyterian missionary in Korea who is most prominently remembered as the founder of the predecessor to Yonsei University, and (probably) Lousia S. Rothwilder, who worked with Mrs. Mary F. Scranton at Ewha and succeeded her as principal. -

Maryknoll Mission Institute

Cenacle Sisters Retreat Center, Ronkonkoma, Long received numerous awards. Blessed Among Women and ecology. His recent books include: Science and Island, offering retreats and teaching spirituality. (Crossroads, 2007) and All Saints: Daily Reflections Faith: A New Introduction (Paulist Press, 2013) and 2016 Programs He holds a doctorate in spirituality from Duquesne on Saints, Prophets and Witnesses for our Time Making Sense of Evolution: Darwin, God, and the University. He has authored The Misfit: Haunting (Crossroads, 1997), are the basis for this program. Drama of Life (Westminster John Knox Press, 2010). the Human-Unveiling the Divine (Orbis, 1997). Dorothy Day had a great influence on Robert’s life. He lectures internationally on issues related to science He worked as editor of the Catholic Worker and edit- and religion. Maryknoll ed the published diaries and letters of Dorothy Day. AWAKENING THE HEART, MENDING THE WORLD: Mission Merton’s Path to Mercy EMBODYING THE OPTION FOR THE POOR Peoples of all faiths and cultures are welcome. June 26 – July 1, 2016 July 17-22, 2016 We invite you to join us for one or more programs. Institute ercy, always in everything mercy.” Pope his program leads participants in exploring the “MFrancis has called for this year to be a Jubi- Tessential theological insights of preferential lee of Mercy. Beginning with an exploration of the option for the poor by understanding the context out epiphanies of mercy that Merton experienced, this of which the phrase arose and by addressing current Cost of 5-day Programs at Maryknoll, NY program will explore the essential themes of his spiri- contexts in which we engage in mission, spiritual tuality - contemplation, compassion and unity - so we development and evangelization. -

The Church's Marines: Maryknollers Older, Fewer, but Still Going Strong

The church’s Marines: Maryknollers older, fewer, but still going strong COCHABAMBA, Bolivia – Their numbers are down, their average age is up, and their last names are as likely to be Vu or Gonzalez as Kelly or O’Brien, but one thing that has not changed about Maryknoll priests and brothers in the past century is their commitment to live and work among the poor in distant lands and unfamiliar cultures. One of Maryknoll’s greatest contributions to Catholic mission has been “seeing and affirming the value and individual worth of all people and all cultures,” Father Raymond Finch, Maryknoll superior general from 1996 to 2002, told Catholic News Service. “That has been (true) from the beginning, whether it was in China or in Latin America, with indigenous cultures,” said Father Finch, 62, who currently directs the Maryknoll Mission Center in Cochabamba. “Especially seeing the contribution, the worth and the beauty in people who are on the margins and who have been hurt by society, the marginalized, the poor – that has been something that we have been blessed with.” The mission sites around the globe where Maryknoll priests and brothers work with refugees, AIDS patients, farmers, children and youth may not be what Fathers James Anthony Walsh and Thomas Frederick Price had in mind when they founded the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America in June 1911 to send missionaries to China. The first priests arrived in China in 1918, and missions in Korea followed. Political upheaval in those countries forced Maryknollers to leave for a time, and the society expanded to Latin America in 1942 and Africa in 1946.