The Catholic Church in China: a New Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12Th 14Th Centuries)

Orientalia biblica et christiana 18 East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12th–14th centuries) Bearbeitet von Li Tang 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. XVII, 169 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 447 06580 1 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 550 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Christliche Kirchen & Glaubensgemeinschaften Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Li Tang East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China 2011 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 09465065 ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1 III Acknowledgement This book is the outcome of my research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund (Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, abbreviated as FWF) from May 2005 to April 2008. It could not be made possible without the vision of FWF in its support of researches and involvement in the international scientific community. I take this opportunity to give my heartfelt thanks, first and foremost, to Prof. Dr. Peter Hofrichter who has developed a passion for the history of East Syrian Christianity in China and who invited me to come to Austria for this research. He and his wife Hilde, through their great hospitality, made my initial settling-in in Salzburg very pleasant and smooth. My deep gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Dietmar W. Winkler who took over the leadership of this project and supervised the on-going process of the research out of his busy schedule and secured all the ways and means that facilitated this research project to achieve its goals. -

Ricci (Matteo)

Ricci (Matteo) 利瑪竇 (1552-1610) Matteo Ricci‟s portrait painted on the 12th May, 1610 (the day after Ricci‟s death 11-May-1610) by the Chinese brother Emmanuel Pereira (born Yu Wen-hui), who had learned his art from the Italian Jesuit, Giovanni Nicolao. It is the first oil painting ever made in China by a Chinese painter.The age, 60 (last word of the Latin inscription), is incorrect: Ricci died during his fifty-eighth year. The portrait was taken to Rome in 1614 and displayed at the Jesuit house together with paintings of Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier. It still hangs there. Matteo Ricci was born on the 6th Oct 1552, in central Italy, in the city of Macerata, which at that time was territory of the Papal State. He first attended for seven years a School run by the Jesuit priests in Macerata, later he went to Rome to study Law at the Sapienza University, but was attracted to the religious life. In 1571 ( in opposition to his father's wishes), he joined the Society of Jesus and studied at the Jesuit college in Rome (Collegio Romano). There he met a famous German Jesuit professor of mathematics, Christopher Clavius, who had a great influence on the young and bright Matteo. Quite often, Ricci in his letters from China will remember his dear professor Clavius, who taught him the basic scientific elements of mathematics, astrology, geography etc. extremely important for his contacts with Chinese scholars. Christopher Clavius was not a wellknown scientist in Europe at that time, but at the “Collegio Romano”, he influenced many young Jesuits. -

Protestants in China

Background Paper Protestants in China Issue date: 21 March 2013 (update) Review date: 21 September 2013 CONTENTS 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................... 2 2. History ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Number of Adherents ................................................................................................................ 3 4. Official Government Policy on Religion .................................................................................. 4 5. Three Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) and the China Christian Council (CCC) ................... 5 6. Registered Churches .................................................................................................................. 6 7. Unregistered Churches/ Unregistered Protestant Groups .......................................................... 7 8. House Churches ......................................................................................................................... 8 9. Protestant Denominations in China ........................................................................................... 9 10. Protestant Beliefs and Practices ............................................................................................ 10 11. Cults, sects and heterodox Protestant groups ........................................................................ 14 -

1 Tribute to Maryknoll Missionary Bishop William J

1 TRIBUTE TO MARYKNOLL MISSIONARY BISHOP WILLIAM J. McNAUGHTON, MM Most Reverend John O. Barres Bishop of the Diocese of Rockville Centre February 8, 2020 The beautiful picture of Maryknoll Bishop William J. McNaughton, MM, Emeritus Bishop of Inchon, Korea and the Maryknoll Mission Archives obituary and synthesis of his global missionary spirit below express so powerfully the charisms of this great Churchman who died on February 3, 2020. I look forward to concelebrating his funeral Mass with Cardinal Sean O’Malley and Bishop McNaughton’s Maryknoll brother priests on Tuesday, February 11, 2020 at 11:00am at Our Lady of Good Counsel—St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Methuen, MA. Bishop McNaughton’s friendship with my convert Protestant minister parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, and our entire family has had a profound impact on our destinies. My parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, met each other at the Yale Divinity School after World War II and both were ordained Congregational Protestant ministers and served at a rural parish in East Windsor, Connecticut outside of Hartford. They had an excellent theological education at Yale Divinity School with such Protestant scholars as Richard and Reinhold Niehbuhr, Paul Tillich and the Martin Luther expert Church historian Roland Bainton. In his book One Shepherd, One Flock (published by Sheed and Ward in 1955 and republished by Catholic Answers in 2000), my father Oliver describes the spiritual and intellectual journey he and my mother Marjorie experienced 2 after their marriage and ordination as Congregational ministers which led to their conversion to the Catholic Church in 1955. -

Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China

religions Article Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China Michel Chambon Anthropology Department, Hanover College, Hanover, IN 47243, USA; [email protected] Received: 25 June 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: This article explores the evolution of female religious life within the Catholic Church in China today. Through ethnographic observation, it establishes a spectrum of practices between two main traditions, namely the antique beatas and the modern missionary congregations. The article argues that Chinese nuns create forms of religious life that are quite distinct from more universal Catholic standards: their congregations are always diocesan and involved in multiple forms of apostolate. Despite the little attention they receive, Chinese nuns demonstrate how Chinese Catholics are creative in their appropriation of Christian traditions and their response to social and economic changes. Keywords: christianity in China; catholicism; religious life; gender studies Surveys from 2015 suggest that in the People’s Republic of China, there are 3170 Catholic religious women who belong to 87 registered religious congregations, while 1400 women belong to 37 unregistered ones.1 Thus, there are approximately 4570 Catholics nuns in China, for a general Catholic population that fluctuates between eight to ten million. However, little is known about these women and their forms of religious life, the challenges of their lifestyle, and their current difficulties. Who are those women? How does their religious life manifest and evolve within a rapidly changing Chinese society? What do they tell us about the Catholic Church in China? This paper explores the various forms of religious life in Catholic China to understand how Chinese women appropriate and translate Catholic religious ideals. -

Maryknoll Alumnae News

Maryknoll Alumnae News Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital (OLMH), Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong In 1957, in response to the thousands of refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong from mainland China, Maryknoll Sisters obtained permission from the Hong Kong Government and received a land grant in Wong Tai Sin to build a hospital to serve the poor. With the help of the Far East Refugee Program of the American Foreign Service, Hong Kong Land Grant and Catholic Relief Services, OLMH was officially opened on August 16, 1961. (Photos courtesy of Sr. Betty Ann Maheu from her book, Maryknoll Sisters, Hong Kong, Macau, China, 1968-2007) Many programs were initiated in the 1970s: Volunteer Program, Community Nursing Service, School of Nursing, Training Seminarians for Hospital Ministry, and Hospital Pastoral Ministry. Later on, Palliative Care clinic was opened to care for people suffering from cancer, the number one cause of death in Hong Kong. In 1982, the first Hospice Care was started in Hong Kong, like Palliative Care Unit, it was the “first” of these special medical services for the people in Hong Kong. In order to continue to serve the lower income brackets of society, OLMH opted to become one of the 33 public hospitals under the Hospital Authority in October 30, 1987. Fast forward to today: OLMH has undergone many operating and administration changes and has continued to offer more services in the community with new procedures. Magdalen Yum, MSS 1976, recently visited OLMH for a private tour. Following is her latest update and photos of the new wing and latest equipment. -

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers Founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the First American-Based Catholic Foreign Missions Society for Women

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the first American-based Catholic foreign missions society for women. Mary Josephine Rogers, called “Mollie” by her family, was born Oct. 27, 1882, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. After graduating from Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, she earned her teaching certificate. Mary taught for several years at Smith College, followed by teaching assignments in several public elementary and high schools in the Boston area. Interest in Foreign Missions Mary was deeply impacted by the flourishing Protestant Student Volunteer Movement that was sending missionaries around the world. In 1908, due to her growing interest in missionary work, she began volunteering her time to assist Father James Walsh in writing and editing the Catholic Foreign Missionary Society of America’s magazine Field Afar, now known as Maryknoll. In September 1910 at the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal, Canada, Mary realized she shared a passion to develop a foreign missions society based in the United States with Father Walsh and Father Thomas Frederick Price. As a result of this common vision, they founded the Maryknoll Mission Movement. Mary provided assistance to the group from Boston where she had family responsibilities before finally joining them in September 1912. She was given the formal name, “Mary Joseph.” She founded a lay group of women interested in missions known as the Teresians, named after the 16th Century Spanish Catholic nun St. Teresa of Avila. In 1913, both the male and female societies moved to Ossining, New York to a farm renamed “Maryknoll.” The pope recognized the work of the Teresians in 1920, allowing the growing society to be designated as a diocesan religious congregation, officially the Foreign Mission Sisters of St. -

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays ABSTRACT Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. In many ways it is the most striking example of that resurgence. Along with Roman Catholics, as of the 1950s Chinese Protestants carried the heavy historical liability of association with Western domi- nation or imperialism in China, yet they have not only overcome that inheritance but have achieved remarkable growth. Popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. This article first traces the gradual extension of interest in Chinese Protestants from Christian circles to the scholarly world during the last two decades, and then discusses salient characteristics of the Protestant movement today. These include its size and rate of growth, the role of Church–state relations, the continuing foreign legacy in some parts of the Church, the strong flavour of popular religion which suffuses Protestantism today, the discourse of Chinese intellectuals on Christianity, and Protestantism in the context of the rapid economic changes occurring in China, concluding with a perspective from world Christianity. Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. Today, on any given Sunday there are almost certainly more Protestants in church in China than in all of Europe.1 One recent thoughtful scholarly assessment characterizes Protestantism as “flourishing” though also “fractured” (organizationally) and “fragile” (due to limits on the social and cultural role of the Church).2 And popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. -

“China and the Maritime Silk Route”. 17-20 February 1991

International Seminar for UNESCO Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue “China and the Maritime Silk Route”. 17-20 February 1991. Quanzhou, China. China of Marvels Reality of a legend Marie-Claire QUIQUEMELLE, CNRS, Paris Since that day in 53 B.C., at Carrhae in Asia Minor, when the Roman soldiers were dazzled by the bright colors of silk flags held by the Parthian army, the mysterious country associated with the production of that marvelous material, i.e., China, has always occupied a quasi-mythical place in the dreams of the Western people.1 But dreams about far away China have been very different from one epoch to another. One could say, in a rather schematic way, that after the image of a China of Marvels introduced by the medieval travellers, there came the China of Enlightment praised by the Jesuits and 18th century French philosophers, followed at the time of European expansionism and "break down of China", by China of exotics, still much in favour to this day. It may look a paradox that among these three approaches, only the earlier one has been fair enough to China, which for several centuries, especially under the Song and Yuan dynasties, was truly much advanced in most fields, compared to Western countries. It is from the Opium War onwards that the prejudices against China have been the strongest, just at the time when travels being easier to undertake, scholars had found a renewed interest in the study of faraway countries and undertaken new research on the manuscripts left by the numerous medieval travellers who had gone to China. -

Saint Eric of Pordenone Catholic.Net

Saint Eric Of Pordenone Catholic.net A Franciscan missionary of a Czech family named Mattiussi, born at Villanova near Pordenone, Friuli, Italy, about 1286; died at Udine, 14 January 1331. About 1300 he entered the Franciscan Order at Udine. Towards the middle of the thirteenth century the Franciscans were commissioned by the Holy See to undertake missionary work in the interior of Asia. Among the missionaries sent there were John Piano Carpini, William Rubruquis, and John of Montecorvino. Odoric was called to follow them, and in April, 1318, started from Padua, crossed the Black Sea to Trebizond, went through Persia by way of the Tauris, Sultaniah, where in 1318 John XXII had erected an archbishopric, Kasham, Yezd, and Persepolis; he also visited Farsistan, Khuzistan, and Chaldea, and then went back to the Persian Gull. From Hormuz he went to Tana on the Island of Salsette, north of Bombay. Here he gathered the remains of Thomas of Tolentino, Jacopo of Padua, Pietro of Siena, and Demetrius of Tiflis, Franciscans who, a short time before, had suffered martyrdom, and took them with him so as to bury them in China. From Salsette he went to Malabar, Fondaraina (Flandrina) that lies north of Calicut, then to Cranganore that is south of Calicut, along the Coromandel Coast, then to Meliapur (Madras) and Ceylon. He then passed the Nicobar Islands on his way to Lamori, a kingdom of Sumoltra (Sumatra); he also visited Java, Banjarmasin on the southern coast of Borneo, and Tsiompa (Champa) in the southern part of Cochin China, and finally reached Canton in China. -

Thirty Years of Mission in Taiwan: the Case of Presbyterian Missionary George Leslie Mackay

religions Article Thirty Years of Mission in Taiwan: The Case of Presbyterian Missionary George Leslie Mackay Magdaléna Rychetská Asia Studies Centre, Department of Chinese Studies, Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] Abstract: The aims of this paper are to analyze the missionary endeavors of the first Canadian Presbyterian missionary in Taiwan, George Leslie Mackay (1844–1901), as described in From Far Formosa: The Islands, Its People and Missions, and to explore how Christian theology was established among and adapted to the Taiwanese people: the approaches that Mackay used and the missionary strategies that he implemented, as well as the difficulties that he faced. Given that Mackay’s missionary strategy was clearly highly successful—within 30 years, he had built 60 churches and made approximately 2000 converts—the question of how he achieved these results is certainly worth considering. Furthermore, from the outset, Mackay was perceived and received very positively in Taiwan and is considered something of a folk hero in the country even today. In the present-day Citation: Rychetská, Magdaléna. narrative of the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, Mackay is seen as someone whose efforts to establish 2021. Thirty Years of Mission in an independent church with native local leadership helped to introduce democracy to Taiwan. Taiwan: The Case of Presbyterian However, in some of the scholarship, missionaries such as Mackay are portrayed as profit seekers. Missionary George Leslie Mackay. This paper seeks to give a voice to Mackay himself and thereby to provide a more symmetrical Religions 12: 190. https://doi.org/ approach to mission history. -

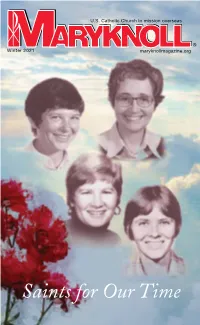

Saints for Our Time from the EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS

U.S. Catholic Church in mission overseas ® Winter 2021 maryknollmagazine.org Saints for Our Time FROM THE EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS n the centerspread of this issue of Maryknoll we quote Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship, which Despite Restrictions of 2 From the Editor Iwas released shortly before we wrapped up this edition and sent it to the COVID-19, a New Priest Is 10 printer. The encyclical is an important document that focuses on the central Ordained at Maryknoll Photo Meditation by David R. Aquije 4 theme of this pontiff’s papacy: We are all brothers and sisters of the human family living on our common home, our beleaguered planet Earth. Displaced by War 8 Missioner Tales The joint leadership of the Maryknoll family, which includes priests, in South Sudan 18 brothers, sisters and lay people, issued a statement of resounding support by Michael Bassano, M.M. 16 Spirituality and agreement with the pope’s message, calling it a historic document on ‘Our People Have Already peace and dialogue that offers a vision for global healing from deep social 40 In Memoriam and economic divisions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We embrace Canonized Them’ by Rhina Guidos 24 the pope’s call,” the statement says, “for all people of good will to commit to 48 Orbis Books the sense of belonging to a single human family and the dream of working together for justice and peace—a call that includes embracing diversity, A Listener and Healer 56 World Watch encounter, and dialogue, and rejecting war, nuclear weapons, and the death by Rick Dixon, MKLM 30 penalty.” 58 Partners in Mission This magazine issue is already filled with articles that clearly reflect the Finding Christmas very interconnected commonality that Pope Francis preaches, but please by Martin Shea, M.M.