The Maryknoll China History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 28, 2001 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial. 4 Question Corner . 23 Respect Life Supplement . 9 TheCCriterionriterion Sunday & Daily Readings. 23 Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org September 28, 2001 Vol. XXXX, No. 50 50¢ In Kazakstan, pope condemns terrorism, begs God to prevent war ASTANA, Kazakstan (CNS)—From “From this place, I invite both Christians earlier, Vatican spokesman Joaquin A large the steppes of Central Asia, a region and Muslims to raise an intense prayer to Navarro-Valls said. poster show- where the United States and Islamic mili- the one, almighty God whose children we With Afghanistan just 200 miles south ing Pope tants appeared headed for confrontation, all are, that the supreme good of peace may of Kazakstan, the pope’s thoughts were John Paul II Pope John Paul II begged God to prevent reign in the world,” he said, switching from clearly on the military showdown that CNS photo from Reuters hangs over war and condemned acts of terrorism car- Russian to English at the end of an outdoor appeared to be developing in the region. the crowd ried out in the name of religion. Mass Sept. 23 in the Kazak capital, Astana. The United States accused Afghanistan of during the Visiting the former Soviet republic of Referring to the suicide hijackings that harboring Islamic militants suspected of papal Mass Kazakstan Sept. 22-25, the pope reached left more than 6,000 dead in the United orchestrating the attacks and was sending in Astana, out to the Muslim majority and asked them States, the pope said: “We must not let troops, ships and planes to the area. -

1 Tribute to Maryknoll Missionary Bishop William J

1 TRIBUTE TO MARYKNOLL MISSIONARY BISHOP WILLIAM J. McNAUGHTON, MM Most Reverend John O. Barres Bishop of the Diocese of Rockville Centre February 8, 2020 The beautiful picture of Maryknoll Bishop William J. McNaughton, MM, Emeritus Bishop of Inchon, Korea and the Maryknoll Mission Archives obituary and synthesis of his global missionary spirit below express so powerfully the charisms of this great Churchman who died on February 3, 2020. I look forward to concelebrating his funeral Mass with Cardinal Sean O’Malley and Bishop McNaughton’s Maryknoll brother priests on Tuesday, February 11, 2020 at 11:00am at Our Lady of Good Counsel—St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Methuen, MA. Bishop McNaughton’s friendship with my convert Protestant minister parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, and our entire family has had a profound impact on our destinies. My parents, Oliver and Marjorie Barres, met each other at the Yale Divinity School after World War II and both were ordained Congregational Protestant ministers and served at a rural parish in East Windsor, Connecticut outside of Hartford. They had an excellent theological education at Yale Divinity School with such Protestant scholars as Richard and Reinhold Niehbuhr, Paul Tillich and the Martin Luther expert Church historian Roland Bainton. In his book One Shepherd, One Flock (published by Sheed and Ward in 1955 and republished by Catholic Answers in 2000), my father Oliver describes the spiritual and intellectual journey he and my mother Marjorie experienced 2 after their marriage and ordination as Congregational ministers which led to their conversion to the Catholic Church in 1955. -

Maryknoll Alumnae News

Maryknoll Alumnae News Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital (OLMH), Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong In 1957, in response to the thousands of refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong from mainland China, Maryknoll Sisters obtained permission from the Hong Kong Government and received a land grant in Wong Tai Sin to build a hospital to serve the poor. With the help of the Far East Refugee Program of the American Foreign Service, Hong Kong Land Grant and Catholic Relief Services, OLMH was officially opened on August 16, 1961. (Photos courtesy of Sr. Betty Ann Maheu from her book, Maryknoll Sisters, Hong Kong, Macau, China, 1968-2007) Many programs were initiated in the 1970s: Volunteer Program, Community Nursing Service, School of Nursing, Training Seminarians for Hospital Ministry, and Hospital Pastoral Ministry. Later on, Palliative Care clinic was opened to care for people suffering from cancer, the number one cause of death in Hong Kong. In 1982, the first Hospice Care was started in Hong Kong, like Palliative Care Unit, it was the “first” of these special medical services for the people in Hong Kong. In order to continue to serve the lower income brackets of society, OLMH opted to become one of the 33 public hospitals under the Hospital Authority in October 30, 1987. Fast forward to today: OLMH has undergone many operating and administration changes and has continued to offer more services in the community with new procedures. Magdalen Yum, MSS 1976, recently visited OLMH for a private tour. Following is her latest update and photos of the new wing and latest equipment. -

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers Founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the First American-Based Catholic Foreign Missions Society for Women

MARY JOSEPH ROGERS Mother Mary Joseph Rogers founded the Maryknoll Sisters, the first American-based Catholic foreign missions society for women. Mary Josephine Rogers, called “Mollie” by her family, was born Oct. 27, 1882, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. After graduating from Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, she earned her teaching certificate. Mary taught for several years at Smith College, followed by teaching assignments in several public elementary and high schools in the Boston area. Interest in Foreign Missions Mary was deeply impacted by the flourishing Protestant Student Volunteer Movement that was sending missionaries around the world. In 1908, due to her growing interest in missionary work, she began volunteering her time to assist Father James Walsh in writing and editing the Catholic Foreign Missionary Society of America’s magazine Field Afar, now known as Maryknoll. In September 1910 at the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal, Canada, Mary realized she shared a passion to develop a foreign missions society based in the United States with Father Walsh and Father Thomas Frederick Price. As a result of this common vision, they founded the Maryknoll Mission Movement. Mary provided assistance to the group from Boston where she had family responsibilities before finally joining them in September 1912. She was given the formal name, “Mary Joseph.” She founded a lay group of women interested in missions known as the Teresians, named after the 16th Century Spanish Catholic nun St. Teresa of Avila. In 1913, both the male and female societies moved to Ossining, New York to a farm renamed “Maryknoll.” The pope recognized the work of the Teresians in 1920, allowing the growing society to be designated as a diocesan religious congregation, officially the Foreign Mission Sisters of St. -

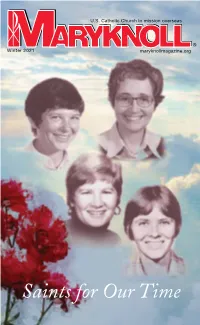

Saints for Our Time from the EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS

U.S. Catholic Church in mission overseas ® Winter 2021 maryknollmagazine.org Saints for Our Time FROM THE EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS n the centerspread of this issue of Maryknoll we quote Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship, which Despite Restrictions of 2 From the Editor Iwas released shortly before we wrapped up this edition and sent it to the COVID-19, a New Priest Is 10 printer. The encyclical is an important document that focuses on the central Ordained at Maryknoll Photo Meditation by David R. Aquije 4 theme of this pontiff’s papacy: We are all brothers and sisters of the human family living on our common home, our beleaguered planet Earth. Displaced by War 8 Missioner Tales The joint leadership of the Maryknoll family, which includes priests, in South Sudan 18 brothers, sisters and lay people, issued a statement of resounding support by Michael Bassano, M.M. 16 Spirituality and agreement with the pope’s message, calling it a historic document on ‘Our People Have Already peace and dialogue that offers a vision for global healing from deep social 40 In Memoriam and economic divisions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We embrace Canonized Them’ by Rhina Guidos 24 the pope’s call,” the statement says, “for all people of good will to commit to 48 Orbis Books the sense of belonging to a single human family and the dream of working together for justice and peace—a call that includes embracing diversity, A Listener and Healer 56 World Watch encounter, and dialogue, and rejecting war, nuclear weapons, and the death by Rick Dixon, MKLM 30 penalty.” 58 Partners in Mission This magazine issue is already filled with articles that clearly reflect the Finding Christmas very interconnected commonality that Pope Francis preaches, but please by Martin Shea, M.M. -

The Catholic Church in China: a New Chapter

The Catholic Church in China: A New Chapter PETER FLEMING SJ with ISMAEL ZULOAGA SJ Throughout the turbulent history of Christianity in China, Christians have never numbered more than one per cent of China's total population, but Christianity has never died in China as many predicted it eventually would. One could argue that Christianity's influence in China has been greater than the proportion of its Christians might warrant. Some have argued that Christianity became strong when Chinese governments were weak: What we seem to be witnessing today in China, however, is a renewal of Christianity under a vital communist regime. That Christianity is in some ways becoming stronger today under a communist regime than it was before the communists is an irony of history which highlights both the promise and the burden of Christianity's presence in China. Today China is no less important in the history of Christianity than she was during Francis Xavier's or Matteo Ricci's time. There are one billion Chinese in China today and 25 million overseas Chinese. These numbers alone tell us of China's influence on and beneficial role for the future and the part that a culturally indigenous Chinese Christianity might play in that future. There is a new look about China today. What does Christianity look like? What has it looked like in the past? The promise and burden of history The Nestorians first brought Christianity to China in the seventh century. The Franciscans John of PIano Carpini and John of Montecorvino followed them in the 13th century. -

Colorado K. of C. Will Train Uy Apostolate

COLORADO K. OF C. WILL TRAIN U Y APOSTOLATE FINE CAREERS Contents Copyrighted— Permission to Reproduce Giveh After 12 M. fe d a y Following Issue EVIDENCE GUILD Colorado CathoUci regard with great sympathy the battle of Cali* rornia prirate, non-profit schools BY GRADUATES WORK WILL b e to rid themseWes of haring to pay DENVER CATHOLIC taxes. The burden of many Cath U C I ' I T CIS v « i n v^ iv. Q j y Q j . olic parishes with schools has been unspeakable. When the writer was in California last fall, he was told FROM LORETTO hy a priest of one of the. large parishes that a check for ^ ,0 0 0 , representing the year’s taxes, had 101 ‘Seculars’ and 63 Religious Have Ob just been sent in. Just imagine New National Movement of Order to Get the annual anguish of making up tained Degrees From College a sum like that, on top of all First Start in Diocese of Denver other expenses. The parish in question was going badly into the ^ ; (By Marie McNamara) Colorado took the lead in one of the biggest move red. No wonder! The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Have ments being sponsored by the Church in America when In Denver in the month of June several hundreds of Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, and Seven Smaller Services. the state convention of the Knights of Columbus, meeting The chief obstacle in the way high school boys and girls, college men and women, will at Canon City May 28 and 29, decided upon the establish of relieving the private schools of be thrust upon the ^orld in the form of graduation. -

THE MARYKNOLL SOCIETY and the FUTURE a PROPOSAL William B

THE MARYKNOLL SOCIETY AND THE FUTURE A PROPOSAL William B. Frazier MM As the third Christian millennium unfolds, Society members are well aware that our numbers are steadily declining. Regions are merging, promotion houses are closing, and efforts are being made to tighten the structures of leadership. The occasion of this paper is an awareness that another step may need to be taken to deal realistically with the situation in which we find ourselves today. Some Society-wide reflection needs to begin regarding the fu- ture of the Society as a whole. In addition to the measures now being taken to right-size and restructure ourselves, should there not be an effort to develop some contingency plans aimed at a time when we might be reduced to a to- ken presence in the countries and peoples we now serve and have such a step forced upon us? What follows is a pro- posal to get the membership thinking about the future of Maryknoll in terms that go beyond the internal adjusting currently under way. On every level of the Society we need to surface scenarios about the Society’s future in face of the possibil- ity of severely reduced membership. It is a matter of preparing ourselves in advance for a series of developments beyond our control, developments that will no longer yield to more and better intra-Societal adjustments. In order to put some flesh on these bones, let me present two scenarios that might be considered. Scenario #1 The Maryknoll Society would remain basically what it is at present and would learn to live and be produc- tive with relatively few permanent members. -

Winnovative HTML to PDF Converter for .NET

ARCS homepage The Archival Spirit, March (Spring) 2006 Newsletter of the Archivists of Religious Collections Section, Society of American Archivists Contents l From the Chair l Small Archive - Small Budget l Archdiocese of Toronto Website l St. Jude Microfilm and Index Available l Membership Directory Update l Virtual Tour: Maryknoll Mission Archives l ARCS Officers and Editor's Note From the Chair By Loretta Greene If according to the adage, “Times flies when you are having fun,” then I must be having a ball! How about you? It’s the end of March, which means the SAA conference is four months away and year-end holidays are only nine months away. “Wait!” you cry, “I’m already in the deep end of the pool and rapidly treading water. Don’t make it worse!” Actually, I am inviting you to take a breather, grab your favorite beverage, and relax with this issue of Archival Spirit – it has much to offer. First, let me tell you that I really am having a ball this year. It is hectic, but a ball. This year the Sisters of Providence in the Northwest are celebrating the 150th anniversary of their arrival in the Northwest and my staff and I are deep in research and preparations. Anyone who has been involved in similar anniversaries (like Father Ralph, below) is nodding knowingly. What amazes me most is the new interpretations of passages in letters that I have read hundreds of times before, the clearer connection between facts and events, and a deeper understanding of relationships. It was all there before and we thought we understood it but in our hectic planning for the sesquicentennial we are also slowing down to listen and are gaining a new understanding. -

Ontario Maryknollers

April 2011 Spring Edition Ontario Maryknollers Official Newsletter of Maryknoll Convent Former Students (Ont.) Committee Members 2010~2012 Important Announcement The next WWR will be in Toronto. President Jacqueline Lam Fong Please read the letter from Sr. Jeanne. Vice-Presidents Linda da Rocha Little Nena Prata Noronha Treasurers Lily Wong Yeung Patricia Ho Wu Secretaries Irene Legay Dear Maryknollers, Wendy Man th During our 7 WWR celebration dinner on February 21, 2010, Maryknollers Newsletter Production voted to have the next reunion in Vancouver. Unfortunately, they are not able Gertrude Chan to do this and asked the Toronto Chapter to take it. Toronto graciously re- plied “yes”. To make the celebration more meaningful, the Toronto girls Activities th Marie Louise Rocha Chang asked to co-celebrate their Chapter‟s 30 Anniversary and the WWR in 2014. Marilyn Hall Pun I support this decision and know that you too will understand that circum- stances have changed our original plans. Membership/Directory Ludia Au Fong Sr. Jeanne Houlihan Web-site Administrator Gertrude Chan Mailing Address: P.O. Box 20056 Nymark Postal Outlet 4839 Leslie Street North York, ON. M2J 5E4 Web Site: http:// www.mcsontario.org E-mail Address for 8th Worldwide Reunion mcswwr2014 @gmail.com April 2011 Spring Edition, p.2 January 14, 2011 Dear Jacqueline and New Committee Members, I am writing this to congratulate you for being elected to the Members Committee for 2010 to 2012. We thank you for accepting such important positions to give a bonding force to all the Maryknollers Ontario, to continue the Maryknoll family spirit, caring for one another; to carry out the legacy of the Maryknoll spirit handed down to you by Mother Mary Joseph, our Foundress, through the Maryknoll Sisters, and to lavish boundless love on the Maryknoll Sisters. -

DELIQUENT TAX SALES KENOSHA, STATE WISCONSIN the Following

DELIQUENT TAX SALES KENOSHA, STATE WISCONSIN The following is a true and correct list of all unredeemed lots, parcels or pieces of land situated, lying and being in the County of Kenosha, State of Wisconsin, which pieces were sold by the County Treasurer of said Kenosha County, state aforesaid on the 31st day of August, 2017 for unpaid taxes if 2016 and charges thereon pursuant to the statutes in such cases made and provided, calculated thereon up to and including the last day of redemption of the same to wit: August 31, 2019.' Now, therefore, notice is hereby given that unless such lots, parcels, or pieces of land are redeemed as provided by law, on or before the 31st day of August, 2019, the said land represented by certificates of sale by the County Treasurer of the county of Kenosha, Wisconsin, of the parcels therein described, will be conveyed to the legal owners of said certificates (Kenosha County) upon proper application according to the statutes of the State of Wisconsin, is such cases made and provided. Given under my hand and seal on this 31st day of January, 2019. Teri Jacobson County Treasurer Kenosha County, Wisconsin CITY OF KENOSHA 01-122-01-103-007 ARMANDO HUIZAR CERT.# 1152 TAX 745.89 01-122-01-103-015 KK WI LQ I LLC CERT.# 1154 TAX 2,491.06 01-122-01-103-019 ALGERNON SPEED CERT.# 1156 TAX 1,560.60 01-122-01-104-004 SANTOS A CRUZ MARADIAGA CERT.# 1157 TAX 157.25 01-122-01-106-002 YUBA DUPREE BARBATO CERT.# 1162 TAX 1,479.35 SPECIAL 766.71 01-122-01-153-005 JAMES ERVING HARPER CERT.# 1177 TAX 520.58 01-122-01-154-029 -

Missiological Reflections on the Maryknoll Centenary

Missiological Reflections on the Maryknoll Centenary: Maryknoll Missiologists’ Colloquium, June 2011 This year Maryknoll celebrates its founding as the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America. In the early 1900s, the idea of founding a mission seminary in the United States circulated among the members of the Catholic Missionary Union. Archbishop John Farley of New York had suggested the establishment of such a seminary, and also tried to entice the Paris Foreign Mission Society to open an American branch. Finally, two diocesan priests, Fathers James Anthony Walsh and Thomas Frederick Price, having gained a mandate to create a mission seminary from the archbishops of the United States, travelled to Rome and received Pope Pius X’s permission to do so. The date was June 29, 1911, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. In the years since, well over a thousand Maryknoll priests and Brothers have gone on mission to dozens of countries throughout the world. Many died young in difficult missions, and not a few have shed their blood for Christ. This is a time to celebrate the glory given by Christ to His relatively young Society. The main purpose of this event, though, is not to glory in our past. We celebrate principally to fulfill the burning desire of our founders, in words enshrined over the main entrance of the Seminary building, Euntes Docete Omnes Gentes, “Go and teach all nations” (Matthew 28:19). Nearly twenty centuries after Christ gave this command, the Church, during the Second Vatican Council, again defined this as the fundamental purpose of mission, being “sent out by the Church and going forth into the whole world, to carry out the task of preaching the Gospel and planting the Church among peoples or groups who do not yet believe in Christ” (Ad Gentes, 6).