Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Allen?

George Allen's 1~ 000 Days Have Changed Virginia .......................... By Frank B. Atkinson .......................... Mr. Atkinson served in Governor George ALIens economy and society, the fall ofrigid and divisive cabinet as Counselor to the Governor and Direc racial codes, the emergence of the federallevia tor ofPolicy untilSeptembe0 when he returned to than and modern social welfare state, the rise of his lawpractice in Richmond. He is the author of the Cold War defense establishment, the politi "The Dynamic Dominion) )) a recent book about cal ascendancy of suburbia, and the advent of Virginia Politics. competitive two-party politics. Virginia's chief executives typically have not championed change. Historians usually 1keeping with tradition, the portraits ofthe identify only two major reform governors dur sixteen most recent Virginia governors adorn ing this century. Harry Byrd (1926-30) the walls out ide the offices of the current gov reorganized state government and re tructured ernor, George Allen, in Richmond. It is a short the state-local tax system, promoted "pay-as stroll around the third-floor balcony that over you-go" road construction, and pushed through looks the Capitol rotunda, but as one moves a constitutional limit on bonded indebtedne . past the likenesses of Virginia chief executives And Mills Godwin (1966-70,1974-78) imposed spanning from Governor Harry F. Byrd to L. a statewide sales tax, created the community Douglas Wilder, history casts a long shadow. college system, and committed significant new The Virginia saga from Byrd to Wilder is a public resources to education, mental health, Frank B. Atkinson story of profound social and economic change. -

Tethered a COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album

Tethered A COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album Letters to You From Jesus To Give You HOPE and INSTRUCTION as given to Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois as well as Carol Jennings Edited and Compiled by Carol Jennings Cover Illustration courtesy of: Ain Vares, The Parable of the Ten Virgins www.ainvaresart.com Copyright © 2016 Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois Published by Heartdwellers.org All Rights Reserved. 2 NOTICE: You are encouraged to distribute copies of this document through any means, electronic or in printed form. You may post this material, in whole or in part, on your website or anywhere else. But we do request that you include this notice so others may know they can copy and distribute as well. This book is available as a free ebook at the website: http://www.HeartDwellers.org Other Still Small Voice venues are: Still Small Voice Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/claredubois/featured Still Small Voice Facebook: Heartdwellers Blog: https://heartdwellingwithjesus.wordpress.com/ Blog: www.stillsmallvoicetriage.org 3 Foreword…………………………………………..………………………………………..………….pg 6 What Just Happened?............................................................................................................................pg 8 What Jesus wants you to know from Him………………………………………………………....pg 10 Some questions you might have……………………………………………………….....................pg 11 *The question is burning in your mind, ‘But why?’…………………....pg 11 *What do I need to do now? …………………………………………...pg 11 *You ask of Me (Jesus) – ‘What now?’ ………………………….….....pg -

Mary Mason Williams, "The Civil War Centennial and Public Memory In

Copyright. Mary Mason Williams and the Virginia Center for Digital History, University of Virginia. 2005. This work may not be published, duplicated, or copied for any purpose without permission of the author. It may be cited under academic fair use guidelines. The Civil War Centennial and Public Memory in Virginia Mary Mason Williams University of Virginia May 2005 1 Copyright. Mary Mason Williams and the Virginia Center for Digital History, University of Virginia. 2005. This work may not be published, duplicated, or copied for any purpose without permission of the author. It may be cited under academic fair use guidelines. On December 31, 1961, Harry Monroe, a Richmond area radio host for WRVA, described the tendency to look back on past events during his “Virginia 1961” broadcast: “One of man’s inherent characteristics is a tendency to look back. He embraces this tendency because its alternative is a natural reluctance to look forward. Man, for the most part, would prefer to remember what he has experienced, rather than to open a Pandora’s box of things he has yet to undergo.”1 In the same broadcast, Monroe and his partner Lon Backman described the commemorations and parades that took place on the streets of Richmond that year as part of the state’s official “look back” at the Civil War one hundred years later. The Civil War Centennial took place from 1961-1965 as the nation was beset with both international and domestic struggles, the most immediate of which for Virginians was the Civil Rights Movement, which challenged centuries of white supremacy and institutionalized segregation that had remained the social and cultural status quo since Reconstruction. -

Bill Bolling Contemporary Virginia Politics

6/29/21 A DISCUSSION OF CONTEM PORARY VIRGINIA POLITICS —FROM BLUE TO RED AND BACK AGAIN” - THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GOP IN VIRGINIA 1 For the first 200 years of Virginia's existence, state politics was dominated by the Democratic Party ◦ From 1791-1970 there were: Decades Of ◦ 50 Democrats who served as Governor (including Democratic-Republicans) Democratic ◦ 9 Republicans who served as Governor Dominance (including Federalists and Whigs) ◦ During this same period: ◦ 35 Democrats represented Virginia in the United States Senate ◦ 3 Republicans represented Virginia in the United States Senate 2 1 6/29/21 ◦ Likewise, this first Republican majority in the Virginia General Democratic Assembly did not occur until Dominance – 1998. General ◦ Democrats had controlled the Assembly General Assembly every year before that time. 3 ◦ These were not your “modern” Democrats ◦ They were a very conservative group of Democrats in the southern tradition What Was A ◦ A great deal of their focus was on fiscal Democrat? conservativism – Pay As You Go ◦ They were also the ones who advocated for Jim Crow and Massive resistance up until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of in 1965 4 2 6/29/21 Byrd Democrats ◦ These were the followers of Senator Harry F. Byrd, a former Virginia Governor and U.S. Senator ◦ Senator Byrd’s “Byrd Machine” dominated and controlled Virginia politics for this entire period 5 ◦ Virginia didn‘t really become a competitive two-party state until Ơͥ ͣ ǝ, and the first real From Blue To competition emerged at the statewide level Red œ -

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015 A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation “with Honors Distinction in History” in the undergraduate colleges at The Ohio State University by Margaret Echols The Ohio State University May 2015 Project Advisor: Professor David L. Stebenne, Department of History 2 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Mills Godwin, Linwood Holton, and the Rise of Two-Party Competition, 1965-1981 III. Democratic Resurgence in the Reagan Era, 1981-1993 IV. A Return to the Right, 1993-2001 V. Warner, Kaine, Bipartisanship, and Progressive Politics, 2001-2015 VI. Conclusions 4 I. Introduction Of all the American states, Virginia can lay claim to the most thorough control by an oligarchy. Political power has been closely held by a small group of leaders who, themselves and their predecessors, have subverted democratic institutions and deprived most Virginians of a voice in their government. The Commonwealth possesses the characteristics more akin to those of England at about the time of the Reform Bill of 1832 than to those of any other state of the present-day South. It is a political museum piece. Yet the little oligarchy that rules Virginia demonstrates a sense of honor, an aversion to open venality, a degree of sensitivity to public opinion, a concern for efficiency in administration, and, so long as it does not cost much, a feeling of social responsibility. - Southern Politics in State and Nation, V. O. Key, Jr., 19491 Thus did V. O. Key, Jr. so famously describe Virginia’s political landscape in 1949 in his revolutionary book Southern Politics in State and Nation. -

The First Labor History of the College of William and Mary

1 Integration at Work: The First Labor History of The College of William and Mary Williamsburg has always been a quietly conservative town. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century to the time of the Civil Rights Act, change happened slowly. Opportunities for African American residents had changed little after the Civil War. The black community was largely regulated to separate schools, segregated residential districts, and menial labor and unskilled jobs in town. Even as the town experienced economic success following the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in the early 1930s, African Americans did not receive a proportional share of that prosperity. As the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation bought up land in the center of town, the displaced community dispersed to racially segregated neighborhoods. Black residents were relegated to the physical and figurative margins of the town. More than ever, there was a social disconnect between the city, the African American community, and Williamsburg institutions including Colonial Williamsburg and the College of William and Mary. As one of the town’s largest employers, the College of William and Mary served both to create and reinforce this divide. While many African Americans found employment at the College, supervisory roles were without exception held by white workers, a trend that continued into the 1970s. While reinforcing notions of servility in its hiring practices, the College generally embodied traditional southern racial boundaries in its admissions policy as well. As in Williamsburg, change at the College was a gradual and halting process. This resistance to change was characteristic of southern ideology of the time, but the gentle paternalism of Virginians in particular shaped the College’s actions. -

EOB #392: December 18, 1972-January 1, 1973 [Complete

-1- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Aug.-08) Conversation No. 392-1 Date: December 18, 1972 Time: Unknown between 4:13 pm and 5:50 pm Location: Executive Office Building The President met with H. R. (“Bob”) Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman. [This recording began while the meeting was in progress.] Press relations -Ronald L. Ziegler’s briefings -Mistakes -Henry A. Kissinger -Herbert G. Klein -Kissinger’s briefings -Preparation -Ziegler -Memoranda -Points -Ziegler’s briefing -Vietnam negotiations -Saigon and Hanoi -Prolonging talks and war -Kissinger’s briefing Second term reorganization -Julie Nixon Eisenhower Press relations -Unknown woman reporter -Life -Conversation with Ziegler [?] -Washington Post -Interviews -Helen Smith -Washington Post -2- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Aug.-08) Conversation No 392-1 (cont’d) -The President’s conversation with Julie Nixon Eisenhower -Philadelphia Bulletin -Press pool -Washington Star -White House social events -Cabinet -Timing -Helen Thomas -Press room -Washington Star -Ziegler Second term reorganization -Julie Nixon Eisenhower -Job duties -Thomas Kissinger’s press relations -James B. (“Scotty”) Reston -Vietnam negotiations -Denial of conversation -Telephone -John F. Osborne -Nicholas P. Thimmesch -Executive -Kissinger’s sensitivity -Kissinger’s conversation with Ehrlichman -The President’s conversation with Kissinger -Enemies -Respect -Kissinger’s sensitivity -Foreign policy -The President’s trips to the People’s Republic of China [PRC] -

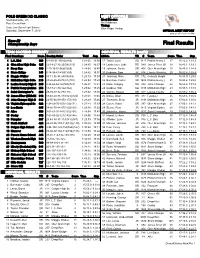

Final Results

POLE GREEN XC CLASSIC MEET OFFICIALS Mechanicsville, VA Meet Director: Pole Green Park Neil Mathews Timing: Host: Lee Davis High School Blue Ridge Timing Saturday, September 7, 2019 OFFICIAL MEET REPORT printed: 9/7/2019 2:19 PM Race #2 Championship Boys Final Results TEAM SCORING SUMMARY INDIVIDUAL RESULTS (cont'd) Final Standings Score Scoring Order Total Avg. Athlete YR # Team Score Time Gap 1 L.C. Bird 108 6-8-30-31-33(82)(166) 1:24:06 16:50 17 Taylor, Luke SO 1417 Patrick Henry ( 17 16:42.2 1:18.2 2 Glen Allen High Scho 125 12-19-27-32-35(59)(115) 1:24:45 16:57 18 Lamberson, Luke SR 589 James River (M 18 16:43.1 1:19.1 3 Deep Run 139 2-13-16-52-56(63)(65) 1:24:04 16:49 19 Johnson, Devin SR 408 Glen Allen High 19 16:48.9 1:24.9 4 Stone Bridge 141 5-14-38-41-43(57)(85) 1:24:42 16:57 20 Rodman, Sam JR 814 Liberty (Bealeto 20 16:52.4 1:28.4 5 Maggie Walker 169 10-11-36-44-68(74)(89) 1:25:13 17:03 21 Jennings, Nate SR 172 Colonial Height - 16:53.0 1:29.0 6 Midlothian High Scho 216 23-26-45-49-73(81)(101) 1:26:53 17:23 22 Burcham, Carter SR 1404 Patrick Henry ( 21 16:53.6 1:29.6 7 Louisa County High S 230 4-24-62-64-76(108)(127) 1:26:41 17:21 23 Dalla, Gregory SR 702 John Champe 22 16:55.4 1:31.4 8 Patrick Henry (Ashlan 254 15-17-21-79-122(162) 1:27:02 17:25 24 Gardner, Will SO 1185 Midlothian High 23 16:55.5 1:31.5 9 Saint Christopher`s 264 29-39-47-72-77(149) 1:27:52 17:35 25 Varney, Bowen SR 917 Louisa County 24 16:59.2 1:35.2 10 James River (Midlothi 316 18-40-58-86-114(123)(124) 1:28:41 17:45 26 Bolles, Brian SR 317 Fauquier 25 16:59.6 -

Mediale Spielräume. Dokumentation Des 17. Film- Und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Barth, Christian Betzer, Jens Eder u.a. (Hg.) Mediale Spielräume. Dokumentation des 17. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14371 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Barth, Thomas; Betzer, Christian; Eder, Jens u.a. (Hg.): Mediale Spielräume. Dokumentation des 17. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums. Marburg: Schüren 2005 (Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftliches Kolloquium 17). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14371. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

Barring October Surprises, Expect a Close Election for the Commonwealth’S Next Governor an Interview with Dr

Barring October surprises, expect a close election for the Commonwealth’s next governor An interview with Dr. Larry J. Sabato By MIKE BELEFSKI Sabato This interview with Dr. Larry J. Sabato, Director of the Center 3. Scandal—NO ADVANTAGE for Politics at The University of Virginia, that I conducted in late Both sides have big problems in this September indicates that on November 5th, we may have a cliffhanger category. It’s GreenTech versus Giftgate— race for governor, a Democratic lieutenant governor, and a toss-up and plenty more besides. BELEFSKI contest for attorney general depending on circumstances that will occur during the last weeks of the 2013 campaign cycle. 4. Campaign Organization/Technology—NO ADVANTAGE Dr. Sabato, who authored “The Ten Keys to the Governor’s I’m not sure about this one yet. McAuliffe has bought the Obama Mansion” published in The University of Virginia Newsletter in voter contact technology that worked so well for the President in 2008 1998 was extremely accurate in analyzing prevailing political party and especially 2012. McAuliffe’s money edge is also enabling him to conditions in the general election for governor. From 1969 to 1977, run a much stronger campaign than Creigh Deeds did four years ago. he analyzed that when Republicans had only one to three advantages, But Cuccinelli has intense support among the GOP base from the Tea the winners were in 1981, Chuck Robb, (D) (53.5%); 1985, Gerald Party, NRA, and pro-life groups. Baliles, (D) (55.2%) and 1969 Doug Wilder, (D) (50.1%). When Democrats had only one to three advantages, the winners were in 5. -

02 CFP Sabato Ch2.Indd

Sabato Highlights✰✰✰ 2 ✰The 2000 Republican ✰✰ ✰Presidential Primary Virginia Finally Matters in Presidential Nominating Politics Overall ☑ The 2000 Republican presidential primary was only the second held in a cen- tury in Virginia (the fi rst being 1988), and it was the fi rst where delegates were actually allocated for the national nominating convention. ☑ Thanks to the strong support of Governor Jim Gilmore and others, Texas Governor George W. Bush won by almost nine percentage points, 52.8 percent to 43.9 percent for Arizona U.S. Senator John McCain. The Virginia victory was a critical step in Bush turning back McCain’s fi erce challenge for the GOP presidential nod. ☑ In part because of Governor Gilmore’s role in the February 29, 2000 primary, President- elect Bush named Gilmore the Republican National Committee chairman aft er the November election. Republican Presidential Primary Election Results ☑ Bush built his Virginia majority in the conservative areas of the state, leaving McCain to garner wins only in moderate Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, where the retired military population appeared to back him. ☑ Though modest in overall size, the Bush majority was broadly based, including 88 of 95 counties and 29 of 39 cities. ☑ Bush was the choice of nearly seven of 10 Republicans, while McCain attracted 87 percent of the Democrats and 64 percent of the Independents voting in Virginia’s “open primary” (open to any registered voter, essentially). Luckily for Bush, the electorate was heavily GOP (63 percent), compared to 29 percent Independent and only eight percent Democratic. Voter Breakdowns ☑ McCain and Bush split male voters about equally, while women tilted heavily to Bush, 57 percent to 41 percent for McCain. -

Past Champions and Competitions

Past Champions and Competitions Class A Virginia High School, Bristol, VA Class AA Bassett High School, Bassett, VA 1st Annual: 1978 Class AAA Roanoke Rapids High School, Roanoke Rapids, NC Marching Bands of America Eastern Regional Championship Class AAAA Heritage High School, Lynchburg, VA (held at JMU) 16th Annual: Oct. 23, 1993 2nd Annual: 1979 Class A Staunton River High School, Moneta, VA Marching Bands of America Eastern Regional Championship Class AA Altavista High School, Altavista, VA (held at JMU) Class AAA Salem High School, Virginia Beach, VA Class AAAA Lake Braddock Secondary, Burke, VA 3rd Annual: Nov. 1, 1980 Marching Bands of America Eastern Regional Championship 17th Annual: Oct. 29, 1994 (held at JMU) Class A Grayson County High School, Independence, VA Class AA Virginia High School, Bristol, VA 4th Annual: Oct. 3, 1981 Class AAA Fiedale-Collinsville High School, Collinsville, VA Marching Bands of America Eastern Regional Championship Class AAAA Greenbriar East High School, Lewisburg, WV (held at JMU) 18th Annual: Oct. 14, 1995 5th Annual: Oct. 30, 1982 Class A George Wythe High School, Wytheville, VA (Florida Citrus Bowl Nominating Contest) Class AA Liberty High School, Bedford, VA Class A Thomas Edison High School, Alexandria, VA Class AAA Fieldale-Collinsville High School, Collinsville, VA Class AA Greenbriar East High School, Lewisburg, WV Class AAAA Norwin High School, North Huntington, PA 6th Annual: Nov. 5, 1983 19th Annual: Oct. 19, 1996 Class A Thomas Edison High School, Alexandria, VA Class A George Wythe High School, Wytheville, VA Class AA Handley High School, Winchester, VA Class AA Lord Botetourt High School, Dalevillle, VA Class AAA Charlottesville High School, Charlottesville, VA Class AAA Fieldale-Collinsville High School, Collinsville, VA Class AAAA Kiski Area High School, Vandergfift, PA 7th Annual: Oct.