Exhibit B.7.6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lonicera Spp

Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html SPECIES: Lonicera spp. Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Fire case studies Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Lonicera spp. AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Munger, Gregory T. 2005. Lonicera spp. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATIONS: LONSPP LONFRA LONMAA LONMOR LONTAT LONXYL LONBEL SYNONYMS: None NRCS PLANT CODES [172]: LOFR LOMA6 LOMO2 LOTA LOXY 1 of 67 9/24/2007 4:44 PM Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html LOBE COMMON NAMES: winter honeysuckle Amur honeysuckle Morrow's honeysuckle Tatarian honeysuckle European fly honeysuckle Bell's honeysuckle TAXONOMY: The currently accepted genus name for honeysuckle is Lonicera L. (Caprifoliaceae) [18,36,54,59,82,83,93,133,161,189,190,191,197]. This report summarizes information on 5 species and 1 hybrid of Lonicera: Lonicera fragrantissima Lindl. & Paxt. [36,82,83,133,191] winter honeysuckle Lonicera maackii Maxim. [18,27,36,54,59,82,83,131,137,186] Amur honeysuckle Lonicera morrowii A. Gray [18,39,54,60,83,161,186,189,190,197] Morrow's honeysuckle Lonicera tatarica L. [18,38,39,54,59,60,82,83,92,93,157,161,186,190,191] Tatarian honeysuckle Lonicera xylosteum L. -

Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi Hanna M. Miller University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Hanna M., "Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi" (2016). Honors Theses. 389. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/389 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi by Hanna Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences May 2016 ii Approved by _________________________________ Mac H. Alford, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract The North American Coastal Plain contains some of the highest plant diversity in the temperate world. However, most of the region has remained unstudied, resulting in a lack of knowledge about the unique plant communities present there. -

WRA.Datasheet.Template (Version 1) (Version 1).Xlsx

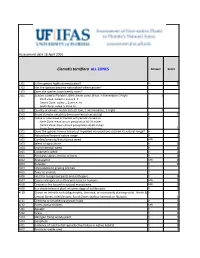

Assessment date 18 April 2016 Clematis terniflora ALL ZONES Answer Score 1.01 Is the species highly domesticated? n 0 1.02 Has the species become naturalised where grown? 1.03 Does the species have weedy races? 2.01 Species suited to Florida's USDA climate zones (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 North Zone: suited to Zones 8, 9 Central Zone: suited to Zones 9, 10 South Zone: suited to Zone 10 2.02 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 2.03 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y 1 2.04 Native or naturalized in habitats with periodic inundation y North Zone: mean annual precipitation 50-70 inches Central Zone: mean annual precipitation 40-60 inches South Zone: mean annual precipitation 40-60 inches 1 2.05 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y 3.01 Naturalized beyond native range y 2 3.02 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed unk 3.03 Weed of agriculture n 0 3.04 Environmental weed y 4 3.05 Congeneric weed y 2 4.01 Produces spines, thorns or burrs n 0 4.02 Allelopathic unk 0 4.03 Parasitic n 0 4.04 Unpalatable to grazing animals ? 4.05 Toxic to animals ? 4.06 Host for recognised pests and pathogens n 0 4.07 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans unk 0 4.08 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems unk 0 4.09 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle n 0 4.10 Grows on infertile soils (oligotrophic, limerock, or excessively draining soils). -

State of Delaware Invasive Plants Booklet

Planting for a livable Delaware Widespread and Invasive Growth Habit 1. Multiflora rose Rosa multiflora S 2. Oriental bittersweet Celastrus orbiculata V 3. Japanese stilt grass Microstegium vimineum H 4. Japanese knotweed Polygonum cuspidatum H 5. Russian olive Elaeagnus umbellata S 6. Norway maple Acer platanoides T 7. Common reed Phragmites australis H 8. Hydrilla Hydrilla verticillata A 9. Mile-a-minute Polygonum perfoliatum V 10. Clematis Clematis terniflora S 11. Privet Several species S 12. European sweetflag Acorus calamus H 13. Wineberry Rubus phoenicolasius S 14. Bamboo Several species H Restricted and Invasive 15. Japanese barberry Berberis thunbergii S 16. Periwinkle Vinca minor V 17. Garlic mustard Alliaria petiolata H 18. Winged euonymus Euonymus alata S 19. Porcelainberry Ampelopsis brevipedunculata V 20. Bradford pear Pyrus calleryana T 21. Marsh dewflower Murdannia keisak H 22. Lesser celandine Ranunculus ficaria H 23. Purple loosestrife Lythrum salicaria H 24. Reed canarygrass Phalaris arundinacea H 25. Honeysuckle Lonicera species S 26. Tree of heaven Alianthus altissima T 27. Spotted knapweed Centaruea biebersteinii H Restricted and Potentially-Invasive 28. Butterfly bush Buddleia davidii S Growth Habit: S=shrub, V=vine, H=herbaceous, T=tree, A=aquatic THE LIST • Plants on The List are non-native to Delaware, have the potential for widespread dispersal and establishment, can out-compete other species in the same area, and have the potential for rapid growth, high seed or propagule production, and establishment in natural areas. • Plants on Delaware’s Invasive Plant List were chosen by a committee of experts in environmental science and botany, as well as representatives of State agencies and the Nursery and Landscape Industry. -

Plastid Phylogenomic Insights Into the Evolution of the Caprifoliaceae S.L. (Dipsacales)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 142 (2020) 106641 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Plastid phylogenomic insights into the evolution of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. T (Dipsacales) Hong-Xin Wanga,1, Huan Liub,c,1, Michael J. Moored, Sven Landreine, Bing Liuf,g, Zhi-Xin Zhua, ⁎ Hua-Feng Wanga, a Key Laboratory of Tropical Biological Resources of Ministry of Education, School of Life and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hainan University, Haikou 570228, China b BGI-Shenzhen, Beishan Industrial Zone, Yantian District, Shenzhen 518083, China c State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Genomics, BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen 518083, China d Department of Biology, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH 44074, USA e Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, 666303, China f State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100093, China g Sino-African Joint Research Centre, Chinese Academy of Science, Wuhan 430074, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The family Caprifoliaceae s.l. is an asterid angiosperm clade of ca. 960 species, most of which are distributed in Caprifoliaceae s.l. temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. Recent studies show that the family comprises seven major Dipsacales clades: Linnaeoideae, Zabelia, Morinoideae, Dipsacoideae, Valerianoideae, Caprifolioideae, and Diervilloideae. Plastome However, its phylogeny at the subfamily or genus level remains controversial, and the backbone relationships Phylogenetics among subfamilies are incompletely resolved. In this study, we utilized complete plastome sequencing to resolve the relationships among the subfamilies of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. and clarify several long-standing controversies. We generated and analyzed plastomes of 48 accessions of Caprifoliaceae s.l., representing 44 species, six sub- families and one genus. -

PRE Evaluation Report for Lonicera Fragrantissima

PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Plant Risk Evaluator -- PRE™ Evaluation Report Lonicera fragrantissima -- Georgia 2017 Farm Bill PRE Project PRE Score: 15 -- Evaluate this plant further Confidence: 65 / 100 Questions answered: 19 of 20 -- Valid (80% or more questions answered) Privacy: Public Status: Submitted Evaluation Date: November 13, 2017 This PDF was created on August 13, 2018 Page 1/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Plant Evaluated Lonicera fragrantissima Image by Kurt Stüber Page 2/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Evaluation Overview A PRE™ screener conducted a literature review for this plant (Lonicera fragrantissima) in an effort to understand the invasive history, reproductive strategies, and the impact, if any, on the region's native plants and animals. This research reflects the data available at the time this evaluation was conducted. Summary Sweet breath of spring (Lonicera fragrantissima) is a deciduous shrub that grows up to 6-10' tall and wide. It bears many small, white, and very fragrant flowers in the early spring, followed by small red berries that grow in early to mid summer. L. fragrantissima is naturalized across much of the Eastern U.S. and is listed on the Georgia and South Carolina EPPC sites as well as by the Tennessee Invasive Plant Council. General Information Status: Submitted Screener: Lila Uzzell Evaluation Date: November 13, 2017 Plant Information Plant: Lonicera fragrantissima Regional Information Region Name: Georgia Climate Matching Map To answer four of the PRE questions for a regional evaluation, a climate map with three climate data layers (Precipitation, UN EcoZones, and Plant Hardiness) is needed. These maps were built using a toolkit created in collaboration with GreenInfo Network, USDA, PlantRight, California-Invasive Plant Council, and The Information Center for the Environment at UC Davis. -

Mistaken Identity? Invasive Plants and Their Native Look-Alikes: an Identification Guide for the Mid-Atlantic

Mistaken Identity ? Invasive Plants and their Native Look-alikes an Identification Guide for the Mid-Atlantic Matthew Sarver Amanda Treher Lenny Wilson Robert Naczi Faith B. Kuehn www.nrcs.usda.gov http://dda.delaware.gov www.dsu.edu www.dehort.org www.delawareinvasives.net Published by: Delaware Department Agriculture • November 2008 In collaboration with: Claude E. Phillips Herbarium at Delaware State University • Delaware Center for Horticulture Funded by: U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Cover Photos: Front: Aralia elata leaf (Inset, l-r: Aralia elata habit; Aralia spinosa infloresence, Aralia elata stem) Back: Aralia spinosa habit TABLE OF CONTENTS About this Guide ............................1 Introduction What Exactly is an Invasive Plant? ..................................................................................................................2 What Impacts do Invasives Have? ..................................................................................................................2 The Mid-Atlantic Invasive Flora......................................................................................................................3 Identification of Invasives ..............................................................................................................................4 You Can Make a Difference..............................................................................................................................5 Plant Profiles Trees Norway Maple vs. Sugar -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

Determination of Taxonomic Status of Chinese Species of the Genus Clematis by Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (Hplc-Ms) Technique

Pak. J. Bot., 42(2): 691-702, 2010. DETERMINATION OF TAXONOMIC STATUS OF CHINESE SPECIES OF THE GENUS CLEMATIS BY USING HIGH PERFORMANCE LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY–MASS SPECTROMETRY (HPLC-MS) TECHNIQUE MUHAMMAD ISHTIAQ CH1, 2*, Q. HE2, S. FENG, YI WANG2, P.G. XIAO2, YIYU CHENG2* AND HABIB AHMED3 1Department of Botany, Mirpur University of Science & Technology (MUST) Bhimber Campus, (AK) Pakistan 2Department of Chinese Medicine Science and Engineering, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Institute of Bioinformatics, Zhejiang University, No. 38 Zhe da Road Hangzhou, 310027, P. R. China 3Department of Botany, University of Hazara, Garden Campus Mansehra, NWFP, Pakistan. Abstract A comparative taxonomic study using chemometric and numerical taxonomic approaches on 15 populations of 12 species of major taxa of the genus Clematis, belonging to sections, Rectae, Clematis, Meclatis, Tubulosae and Viorna were analyzed by HPLC coupled with diode array detector and ESI-MS. The chemodiversity profile of saponins proved to be useful taxonomic markers for the genus and results are presented in phenograms. The compound ‘Huzhangoside D’ was the most abundant in analyzed species of the genus. Numerical taxonomic study was also conducted based on phylogenetically informative characters which corroborated with chemical fingerprinting findings. The significance of chemical markers in taxonomic study as well as their correlation between morphology and chemical compound profile is also debated with its significant role in botanic drugs identification. Introduction Clematis L., is the second largest genus of Ranunculaceae, which comprises of more than 300 species worldwide and among these 147 (93 endemic) species are found in China (Wang, 1999). Traditional classification systems are usually based on floral and vegetative characters, and have been used for taxonomic divisions of many plants. -

SHRUBS & HEDGING ETC Abelia Grandiflora Evergreen Easy to Grow in Most Soil Conditions. Glossy Green Leaves with White Flowe

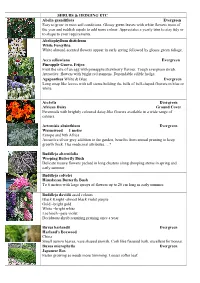

SHRUBS & HEDGING ETC Abelia grandiflora Evergreen Easy to grow in most soil conditions. Glossy green leaves with white flowers most of the year and reddish sepals to add more colour. Appreciates a yearly trim to stay tidy or to shape to your requirements. Abeliophyllum distichum White Forsythia White almond-scented flowers appear in early spring followed by glossy green foliage. Acca sellowiana Evergreen Pineapple Guava, Feijoa Fruit the size of an egg with pineapple/strawberry flavour. Tough evergreen shrub. Attractive flowers with bright red stamens. Dependable edible hedge. Agapanthus White & Blue Evergreen Long strap like leaves with tall stems holding the balls of bell-shaped flowers in blue or white. Arctotis Evergreen African Daisy Ground Cover Perennials with brightly coloured daisy-like flowers available in a wide range of colours. Artemisia absinthium Evergreen Wormwood 1 metre Europe and Nth Africa Attractive silver grey addition to the garden, benefits from annual pruning to keep growth thick. Has medicinal attributes….? Buddleja alternifolia Weeping Butterfly Bush Delicate mauve flowers packed in long clusters along drooping stems in spring and early summer. Buddleja colvelei Himalayan Butterfly Bush To 6 metres with large sprays of flowers up to 20 cm long in early summer. Buddleja davidii asstd colours Black Knight -almost black violet purple Gold –bright gold White –bright white Lochinch –pale violet Deciduous shrub requiring pruning once a year. Buxus harlandii Evergreen Harland’s Boxwood China Small narrow leaves, vase shaped growth. Cork like fissured bark, excellent for bonsai. Buxus microphylla Evergreen Japanese Box Faster growing so needs more trimming. Looser softer leaf. Buxus sempivirens Evergreen English Box Traditional small to medium hedging plant. -

Minnesota's Top 124 Terrestrial Invasive Plants and Pests

Photo by RichardhdWebbWebb 0LQQHVRWD V7RS 7HUUHVWULDO,QYDVLYH 3ODQWVDQG3HVWV 3ULRULWLHVIRU5HVHDUFK Sciencebased solutions to protect Minnesota’s prairies, forests, wetlands, and agricultural resources Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Prioritization Panel members ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Seventeen criteria, and their relative importance, to assess the threat a terrestrial invasive species poses to Minnesota ...................................................................................................................... 5 IV. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive insects ................................................................................. 6 V. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive plant pathogens .................................................................. 7 VI. Prioritized list of plants (weeds) ................................................................................................... 8 VII. Terrestrial invasive insects (alphabetically by common name): criteria ratings to determine threat to Minnesota. .................................................................................................................................... 9 VIII. Terrestrial invasive pathogens (alphabetically by disease among bacteria, fungi, nematodes, oomycetes, parasitic plants, and viruses): criteria ratings -

Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR CUMBERLAND GAP NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Networks Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office March 2006 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. Citation: Rickie D. White, Jr. 2006. Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Durham, North Carolina: NatureServe. © 2006 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama Street, S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant (ecological) communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserveexplorer.org. Cover photo: Red cedar snag above White Rocks at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Photo by Rickie White. ii Acknowledgments I wish to thank all park employees, co-workers, volunteers, and academics who helped with aspects of the preparation, field work, specimen identification, and report writing for this project.