Red Herrings Art's Toxic Assets and a Crisis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antwerp in 2 Days | the Rubens House

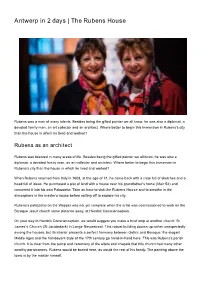

Antwerp in 2 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect Rubens was talented in many areas of life. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. On your way to Hendrik Conscienceplein, we would suggest you make a brief stop at another church: St James’s Church (St Jacobskerk) in Lange Nieuwstraat. This robust building dooms up rather unexpectedly among the houses, but its interior presents a perfect harmony between Gothic and Baroque: the elegant Middle Ages and the flamboyant style of the 17th century go hand-in-hand here. -

Rubenianum Fund Field Trip to Princely Rome, October 2017

2017 The Rubenianum Quarterly 3 Peter Paul Rubens: The Power of Transformation Drawn to drawings: a new collaborative project Mythological dramas and biblical miracles, intimate portraits and vast landscapes – Although the Rubenianum seldom seeks the Peter Paul Rubens’s creative power knew no limits. His ingenuity seems inexhaustible, public spotlight for its scholarship, specialists and his imagination boundless. The special exhibition ‘Kraft der Verwandlung’ institutions in the field know very well where to turn (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 17 October 2017–21 January 2018) sets out to to for broad, grounded and reliable art-historical explore this spirit of innovation, taking an in-depth look at the sources on which the expertise. Earlier this year, the Flemish Government Flemish master drew and how he made them his own. approached us with a view to a possible assignment Rubens had an unrivalled ability to apply his examples freely and creatively. concerning 17th-century drawings. Given that Ignoring the boundaries of genre, he studied the small-scale art of printmaking as well another of the Rubenianum’s unmistakable as monumental oil paintings. The artist’s extensive library provided a further source trademarks is its open and generous attitude to of inspiration, as did antique coins. He took three-dimensional sculptures – bronze statuettes, casts from nature and marble statues – and brought them to life in his collaboration, this task was indeed assigned to paintings. us thanks to a thoroughly prepared partnership Rubens drew, copied and interpreted as he saw fit throughout his life. Existing with the Royal Library of Belgium. We are proud, sources were transformed by his hand into something entirely new. -

Download Programme Antwerp Barok 2018

FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 ANTWERP BAROQUE 2018 BAROQUE ANTWERP PROGRAMME Programme www.antwerpbaroque2018.be Cultural city festival I june 2018 — january 2019 © Paul Kooiker, uit de serie Sunday, 2011 — vu: Wim Van Damme, Francis Wellesplein 1, 2018 Antwerpen 1, 2018 Wellesplein Francis Damme, — vu: Wim Van 2011 uit de serie Sunday, Kooiker, © Paul Paul Kooiker The cover photo was taken by the Dutch photographer Paul Kooiker. See more of his surprising nudes at the FOMU. expo Paul Kooiker 71 Behind the scenes Frieke Janssens The striking portraits in this portrayed. The ostrich feathers brochure were taken by the in Herr Seele’s portrait epitomise Belgian photographer Frieke exoticism and lavish excess. Janssens. “Baroque suits me, it Yvon Tordoir also paints skulls suits my photographic style.” in his street art but a skull also Janssens mainly studied the embodies power, fearlessness and self-portraits of Rubens and the rebelliousness. The soap bubbles in portrait of his wife, Isabella Brant. the portrait of the musician Pieter “I refer to the pose, the attributes, Theuns symbolise the “ephemeral” that same atmosphere in my while the peacock represents photos. People often associate pride and vanity. I thought this Baroque with exuberance and was a perfect element for Stef excess, whereas my portraits are Aerts and Damiaan De Schrijver, almost austere. Chiaroscuro is a who work in the theatre. I chose typically Baroque effect though. herring, the most popular ocean I use natural daylight, which fish in the sixteenth century for makes my photos look almost like the ladies of Alle Dagen Honger. paintings.” I wanted to highlight the female “I also wanted the portraits power of Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven to have a contemporary feel. -

The Bold and the Beautiful

THE BOLD AND IN FLEMISH PORTRAITS THE BEAUTIFUL This is the booklet accompanying THE BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL. In Flemish Portraits exhibition project. The exhibition takes place in four locations in the Antwerp city centre, at short, walkable distances from one another: KEIZERSKAPEL MUSEUM SNIJDERS&ROCKOX HOUSE SAINT CHARLES BORROMEO CHURCH VLEESHUIS MUSEUM Would you like to discover some more historical locations? An optional walking tour leads you along a number of vestiges of the world of the portrayed and brings you back to the starting point of the exhibition, the Keizerstraat. We hope you will enjoy it! Tickets & info: www.blinddate.vlaanderen © The Phoebus Foundation Chancellery vzw, Antwerp, 2020 D/2020/14.672/2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. If you have comments or questions we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: [email protected] THE BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL IN FLEMISH PORTRAITS Make-up: Gina Van den Bergh THIS EXHIBITION WAS CREATED BY The Chancellery of The Phoebus Foundation Editor: Guido Verelst Museum Snijders&Rockox House Grader: Kene Illegems — Sound mix: Yves De Mey A Deep Focus production WITH THE SUPPORT OF KBC Group NV Installation: Create Katoen Natie Projections: Visual Creations Indaver — Jan De Nul Group NV MANNEQUINS Isabelle De Borchgrave and Keizerskapel — Saint Charles Borromeo Church REDACTION AND TRANSLATIONS Vleeshuis Museum Luc Philippe & Patrick De Rynck (NL) Saint Paul’s Church Anne Baudouin & Ted Alkins (EN) Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp — University of Antwerp TEXTS Saint James’ Church Hannah Thijs & Buvetex Katrijn Van Bragt — Dr. -

Stichting CODART

CODART ZESTIEN congress program PROGRAM CODART ZESTIEN congress Old favorites or new perspectives? Dividing your time and attention between the permanent collection and temporary exhibitions Sunday, 21 April 13:00-14:30/ City walking tour: the Viennese fin de siècle with Arnout Weeda 15:00-16:30 17:00-19:00 Congress reception at the Rathaus, Vienna, offered by the City of Rathaus Vienna entrance Lichtenfelsgasse 2 Monday, 22 April Congress chair: Dr. Yao-Fen You, assistant curator of European sculpture and decorative arts, Detroit Institute of Arts 08:45-09:00 Registration at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Kunsthistorisches Museum Burgring 5 09:00-15:00 Opening session in the Bassano Room: Old favorites or new perspectives? Dividing your time and attention between the permanent collection and temporary exhibitions 09:00-09:05 Welcome by Dr. Sabine Margarethe Haag, director general and director of the Kunstkammer and Treasuries of the Kunsthistorisches Museum 09:05-09:10 Welcome by Dr. Sylvia Ferino, director of the Picture Gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum 09:10-09:25 Introduction to the congress program by congress chair 09:25-10:05 Keynote lecture: In the Balance: Finding Time for Collection and Exhibition Catalogues by Dr. Arthur Wheelock, curator of Northern Baroque painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington 10:05-10:50 Coffee and tea in the museum café 10:50-11:30 Keynote lecture: Making the Permanent Collection Matter by Dr. Julien Chapuis, deputy director of the Sculpture Collection and Museum of Byzantine Art, Bode Museum der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin 11:30-11:50 Discussion about the keynote lectures led by the congress chair 11:50-12:10 Lecture on the Kunstkammer by Dr. -

PAINTINGS of PAINTINGS: the RISE of GALLERY PAINTINGS in SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ANTWERP By

PAINTINGS OF PAINTINGS: THE RISE OF GALLERY PAINTINGS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ANTWERP by Charlotte Taylor A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Art History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Paintings of Paintings: The Rise of Gallery Paintings in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Charlotte Taylor Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2016 Director: Angela Ho, Professor, George Mason University Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2018 Charlotte Taylor All Rights Reserved ii Dedication This is dedicated to my mother; whose strength and resilience inspire me every day. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. My mother and father assisted me by editing this paper and helping me develop my ideas. Dr. Angela Ho and Dr. Michele Greet, were of invaluable help, and without them this project never would have come to fruition. Finally, thanks go -

Rubenianum Fund

2021 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 From limbo to Venice, then to London and the Rubenshuis Towards new premises A highlight of the 2019 Word is out: in March, plans for a new building for exhibition at the Palazzo the Rubens House and the Rubenianum, designed by Ducale in Venice (‘From Titian Robbrecht & Daem architecten and located at Hopland 13, to Rubens. Masterpieces from were presented to the world. The building will serve as Flemish Collections’), this visitor entrance to the entire site, and accommodate visitor ravishing Portrait of a Lady facilities such as a bookshop, a café and an experience Holding a Chain is arguably centre. The present absence of such facilities had led to an one of the most exciting initial funding by Visit Flanders, which, in turn, incited the Rubens discoveries of the City of Antwerp to address all infrastructural needs on site. past decade and perhaps the These include several structural challenges that the finest portrait by the artist Rubenianum has faced for decades, such as the need for remaining in private hands. climate-controlled storage for the expanding research The picture is datable to collections. The new building will have state-of-the-art the beginning of Rubens’s storage rooms on four levels, as well as two library career, and was probably floors with study places, in a light and energy-efficient painted either during his architecture. The public reading room on the second floor will be accessible to all visitors via an eye-catching spiral short trip from Mantua to staircase, and will bring the Rubenianum collections Spain (between April 1603 within (visual and physical) reach of all, after their and January 1604), or not somewhat hidden life behind the garden wall. -

Flanders Fields

Received by NSD/F ARA Registration Unit 2014-18• Flanders Fields Flanders· Fields.. A pla<:e to remember. VISIT P:LAN DERS~IELDS1418.COM FLANDERS 5PM Wd ,tdll :i, l lO ·spLie4 pamv u1 peq aq 018u11481J Jo sJea.< mo1- JO s:tJewpue1 Jl!ll!W!?J aij1 JbJ pLie·sanw Ua1 il)LieApe 01 s.<ep ;,aJ41-1'inf :tOOl 11 ·a,..,sLiaJJo:s.<7 ;;.41 Stip["lp 1so1 punoJ8 a41 paJmdeJaJ 8L6L saJdAJO•amee a41 'Jaqwa1das 8L uo 8uivns ! s1Liaw;1edw1 ·sJapue1:1 qBnoJ41 pa:pt!lle .<unJsSaJJns ·sdoon h111qes1p BLI!LIJl!al BLiueaq s1uawJ1edw1 SJOl!S!A pa1qes1p , ·•rn1pue1:1 UI SU0!l1D0I Lie1B1ae pue ·4JuaJ:1 ·4s1l!Ja J.O aJJOJ e 4l!M ·wn181aa "e 4l!M 5J0l!S!A lll!M SJOl\S!A 1ens1A lll!M a1do;,d .llQ!SSclJJe a1epowwo:1Je 01 mno pue ~P1a!:1 sJapul!l:J JoJ uo11ewJ0Ju1 ..{1u1q1ssaJJe JO lJ.lQl"V' 8Ul)I 'lllJOU a41 UI ·sau11 Ul!WJil9 ;nn uo JOJ. sarn1Pe:i JOJ. sam1pe:1 JOJ SU!l!IPl!:I J!l!lJJlil.lM saJnseaw J!ses we11aj.iJ 4l!M iluore ·s1U_a11i3 aA(teJowawwoJ ator s:pene tlleJedas: aaJq11.pune1 01,pappap 'Japueww()<). pue -~611epOWWO)Jl! 'SUO!l\!)01 'Sdl!S ll"IJOWaW ,{al pa1uv awaJdns a41 ·4Jo::1 1eJaua9 ·aJi'1s!WJ'9'·aq1 a~l 01 ap1n8 1e11uassa _ue sap1AoJ~ aJmpoJq .s11.u JO Bu1uB1s iil,ll 411M ptia .<1a1ew111n p1noM llJlllM aA1suaJJ9 slie~ paJpunH a41 ueSaq sa1uv aql ·1sn8nv.u1 (:f ~l i ~.·. / ,~ "SUO!leJOWaUJUJO) illfl Ol ,nnqp1um 01 ,ff 0 . -

Oral History Interview with Clifford Schorer, 2018, June 6-7

Oral history interview with Clifford Schorer, 2018, June 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by Barbara Fleischman. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Clifford Schorer on June 6 and 7, 2018. The interview was conducted by Judith Olch Richards for the Archives of American Art and the Center for the History of Collecting in America at the Frick Art Reference Library of The Frick Collection, and took place at the offices of the Archives of American Art in New York, NY. Clifford Schorer and Judith Olch Richards have reviewed this transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. Researchers should note the timecode in this transcript is approximate. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JUDITH RICHARDS: This is Judith Olch Richards interviewing Clifford J. Schorer III, on June 6, 2018, at the Archives of American Art offices in New York City. CLIFFORD SCHORER: Hello. JUDITH RICHARDS: Hello. Good afternoon. I wanted to start by asking you to say when and where you were born, and to talk about your immediate family, their names, and anyone else who was important to you in your family. CLIFFORD SCHORER: So there are those who were present that were important to me, and there's one figure who was not present who was very important to me. -

The Rubenianum Quarterly

2015 The Rubenianum Quarterly 3 A fine gesture from one of our donors ‘Wow! What a show’ intensifies the bond between scholars and patrons These four words, uttered by the highly esteemed From April to November 2015 Elise Boutsen is strengthening the director of a leading British museum, perfectly Rubenianum ranks as a project associate. Thanks to a generous gift from capture the tone of the praise garnered by the Mr Eric Le Jeune, she is immersing herself in the world of the wooded recent exhibition at the Rubenshuis: ‘Rubens landscape, sifting through the Rubenianum’s paper documentation on in Private. The Master Portrays his Family’ the Frankenthal school and creating some 500 online records in the (28 March–28 June). The show – the first to be dedicated to the more private side of Rubens’s genius, RKDimages database to which the Rubenianum has been contributing featuring a selection of self-portraits and portraits since 2012. Elise improves and adds to our on-site documentation and of family members and friends – attracted more markedly expands the online presence of these Protestant landscape than 100,000 visitors. Similarly, the catalogue artists, who fled Antwerp for Frankenthal after the city’s fall in 1585. (‘beautifully produced and much anticipated’ – Her research will also result in the publication of an article on the subject. HNA Review of Books, August 2015) sold out before the exhibition closed. Mr Le Jeune is passionate about Flemish painting. On arrival at the The public was surprised, above all, by the warm, Rubenianum he enthusiastically reports on a recent visit to the devoted intimacy of the portraits and drawings St Petersburg State Hermitage Museum. -

The Rubenianum Quarterly

2015 The Rubenianum Quarterly 4 The great tradition of Antwerp landscape painting Baroque It is often forgotten that after the early sixteenth-century panoramic landscapes of Joachim After several cultural city projects – including Patinir (c. 1478–1524) and many others, the genre continued to evolve. Up to the first quarter ‘Van Dyck 99’, ‘Mode 2001: Landed/Geland’, of the seventeenth century, several exquisite landscape painters active in the Ant werp region ‘Antwerp World Book Capital ABC2004’, ‘Rubens enjoyed international success. Though pushed to the background by the roaring baroque of 2004’ and ‘Happy Birthday Dear Academie’ – in Rubens and the marvellous portraiture of Van Dyck, these landscapists rarely get the atten- 2018 Antwerp will once again develop a theme tion they deserve. That is why the Rubenianum, with generous private support, has invested in throughout the city. ‘Barok2018’ (working title) research on early seventeenth-century landscape, and will continue to do so in 2016. starts from the premise that baroque is inherently A first goal of the 2015 project was to increase the online presence of Antwerp painters present in the identity and the DNA of the city and like David Vinckboons (1576–1629), Pieter Stevens (c. 1567–c. 1630), Kerstiaen de Keuninck its inhabitants. The starting point of this project is (1551–c. 1635) and Abraham Govaerts (1589–1626) by including a selection of their work in the historical baroque, established in Antwerp by RKDimages. Second, the project included a research campaign on the rather unknown Mar- Rubens, through his house and his art and through ten Ryckaert (Antwerp 1587–1631 Antwerp), who lived and worked in Antwerp during that flourishing period of Antwerp art. -

Rubenianum Fund

2013 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 ‘The Golden Cabinet’. The Royal Museum at the Rockox House An expat in London Imbued with an eternal metropolitan sense, the City of Antwerp twice constructed a Born and bred in Antwerp yet living and working brand-new arts temple to accommodate its unique Rubens collection in the course of the in London taking care of works of art from the Low nineteenth century. The purpose of the monumental programmatic painting by Nicaise Countries, I find it most gratifying to reconnect to de Keyser that adorns the staircase of the museum is immediately apparent: it celebrates my home country through my job. As a curator the Antwerp school of painting, whose very finest pieces await the unsuspecting and in- of Dutch and Flemish drawings and prints at the variably overwhelmed visitors who are about to enter the galleries. British Museum, I couldn’t be luckier: thanks to One of the exquisite products of the Antwerp school is the so-called Kunstkammer or ‘art cabinet’, a rather unique genre that is reminiscent of the city’s Golden Age, when the enthusiasm of many British collectors, the Antwerp was an important centre of production of and trade in luxury goods. Wealthy local Department of Prints and Drawings boasts one of citizens would devote themselves to building inspired collections of art to show off to and the foremost collections of works on paper by Dutch share with their peers. Some of these cabinets were internationally renowned in humanist and Flemish artists. circles and considered an essential ingredient of cultural and intellectual life.